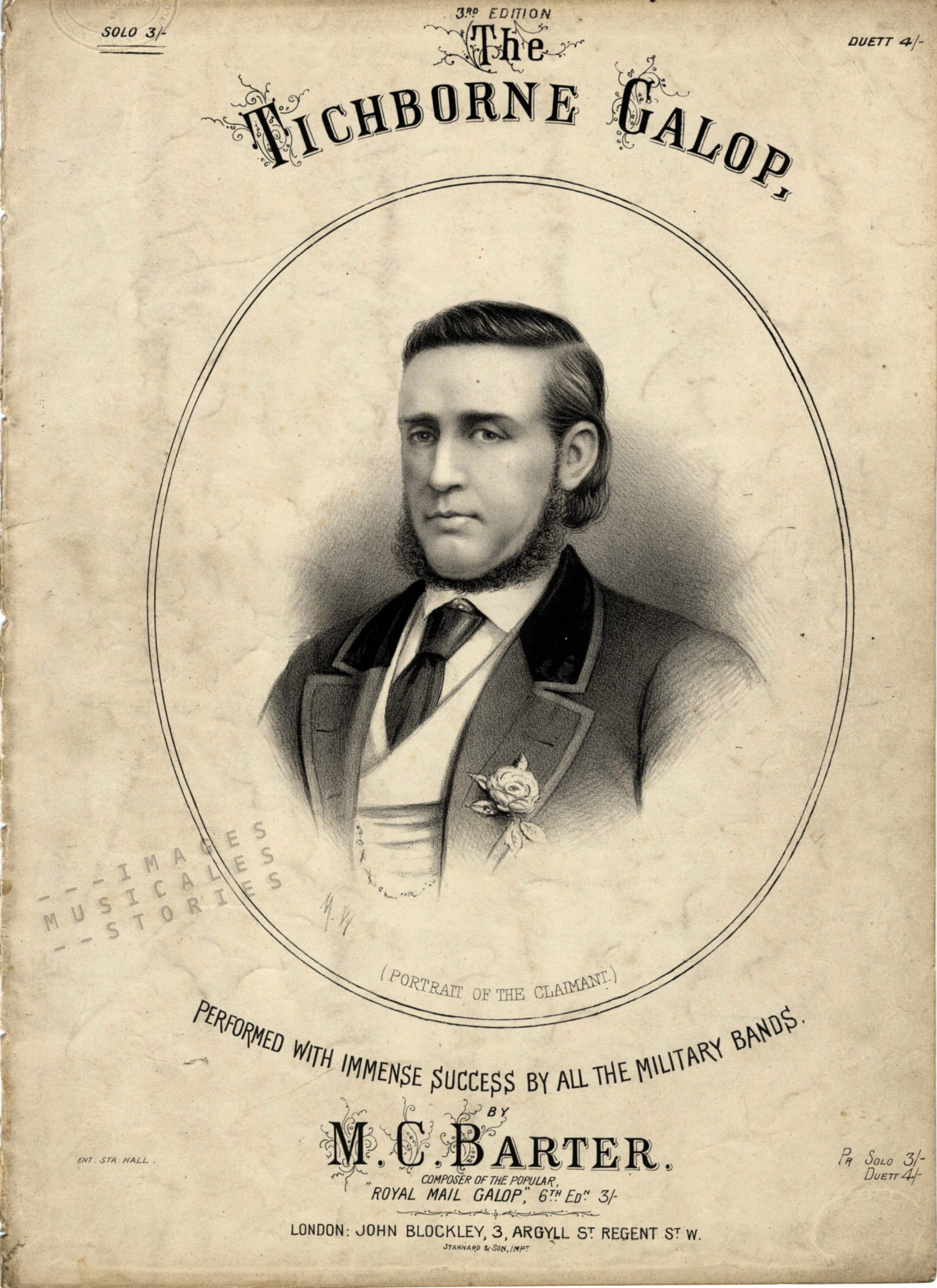

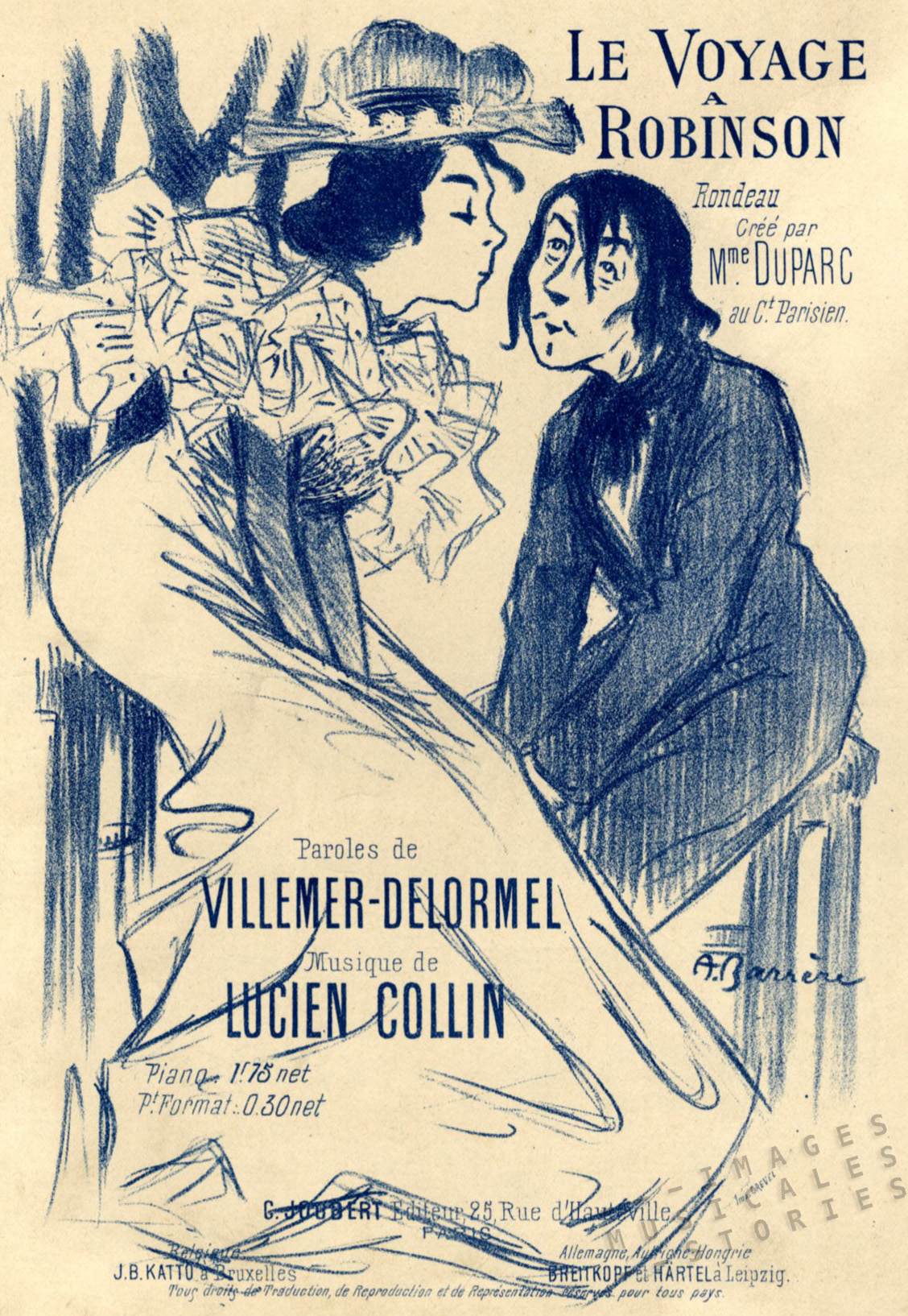

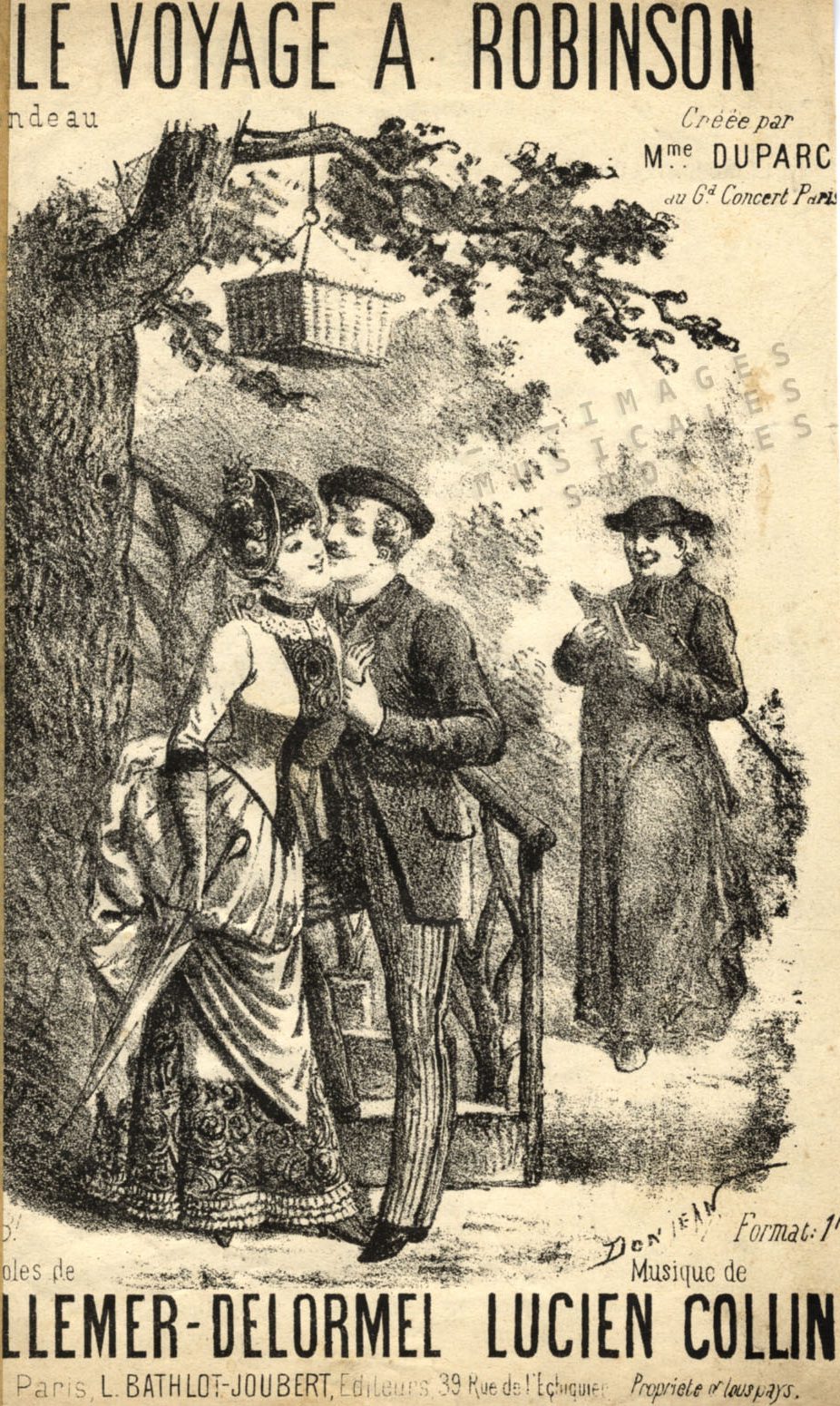

For Le voyage à Robinson the illustrator of the sheet music imagined a girl with puckered lips waiting to be kissed by an artistic young man. The gifted caricaturist Adrien Barrère must have been inspired by the flirtatious liaison described by the lyricists Villemer and Delormel. Their song —first performed in 1884— became a belle-époque classic. It tells the story of an innocent girl taken advantage of during an outing to a village resort called Robinson. Oh no, and the trip started so well though!

Te rappelles-tu le jour de ma fête

Où tu m’emmenas rire à Robinson ?

Nous avions alors de l’amour en tête

Car nos cœurs chantaient la même chanson.

[ Do you remember when on my birthday

you gaily took me for a ride to Robinson?

Both our heads were then filled with love

As our hearts were humming the same song. ]

A few rhymes later the story unbridles a little:

Dans l’arbre fameux je grimpais bien vite

Le vent souleva ma jupe un peu trop

Et toi, curieux, montant à ma suite

En voyant cela, tu crias “Plus haut !”

[ Into the famous tree I quickly climbed

The wind lifted my skirt a bit

And curious you, following behind,

Seeing that cried “Higher up!” ]

Let us hear Annie Girardot sing about the Voyage à Robinson, and how it ends in woeful memories.

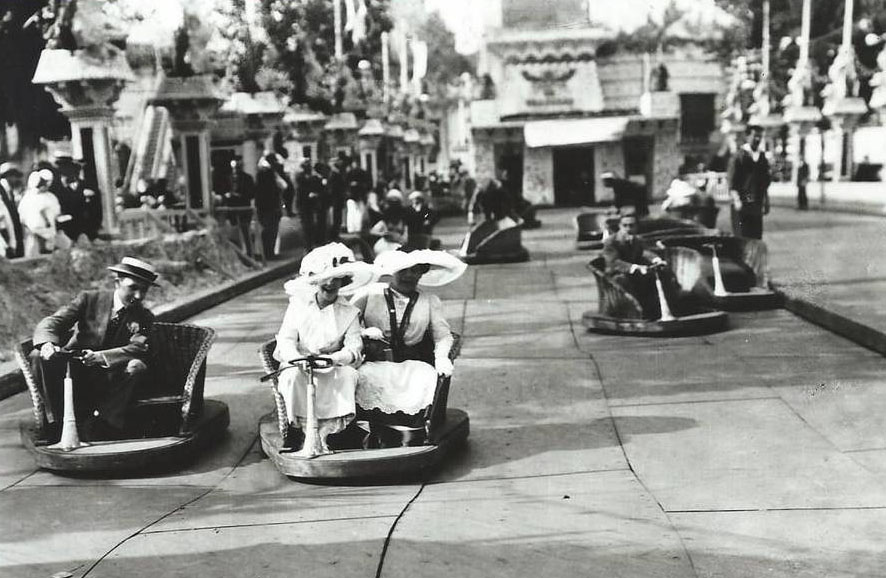

In the 19th and early 20th century guinguettes were a popular destination for Parisian day trippers. A guinguette was an establishment for ample drinking, simple eating and lively dancing. Traditionally it was located next to a river or to a lake in the Parisian suburbs.

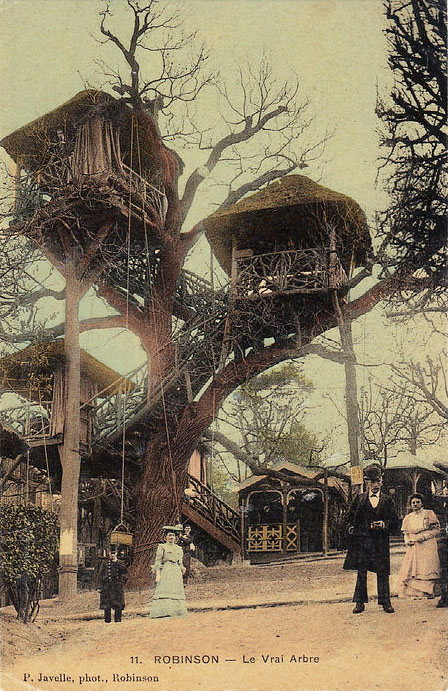

The Robinson guinguettes were situated not along the water but in a forest near Paris. For over a century they attracted a crowd of Parisians who came to relax in the forest on Sunday. It all started with an innkeeper who in 1848 built a suite of interconnected tree houses in a majestic chestnut tree. He named his guinguette Au Grand Robinson. He had confused Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe who lived in a cave and ‘The Swiss Family Robinson’ who lived in a tree house as described by Johann Wyss in his book from 1813.

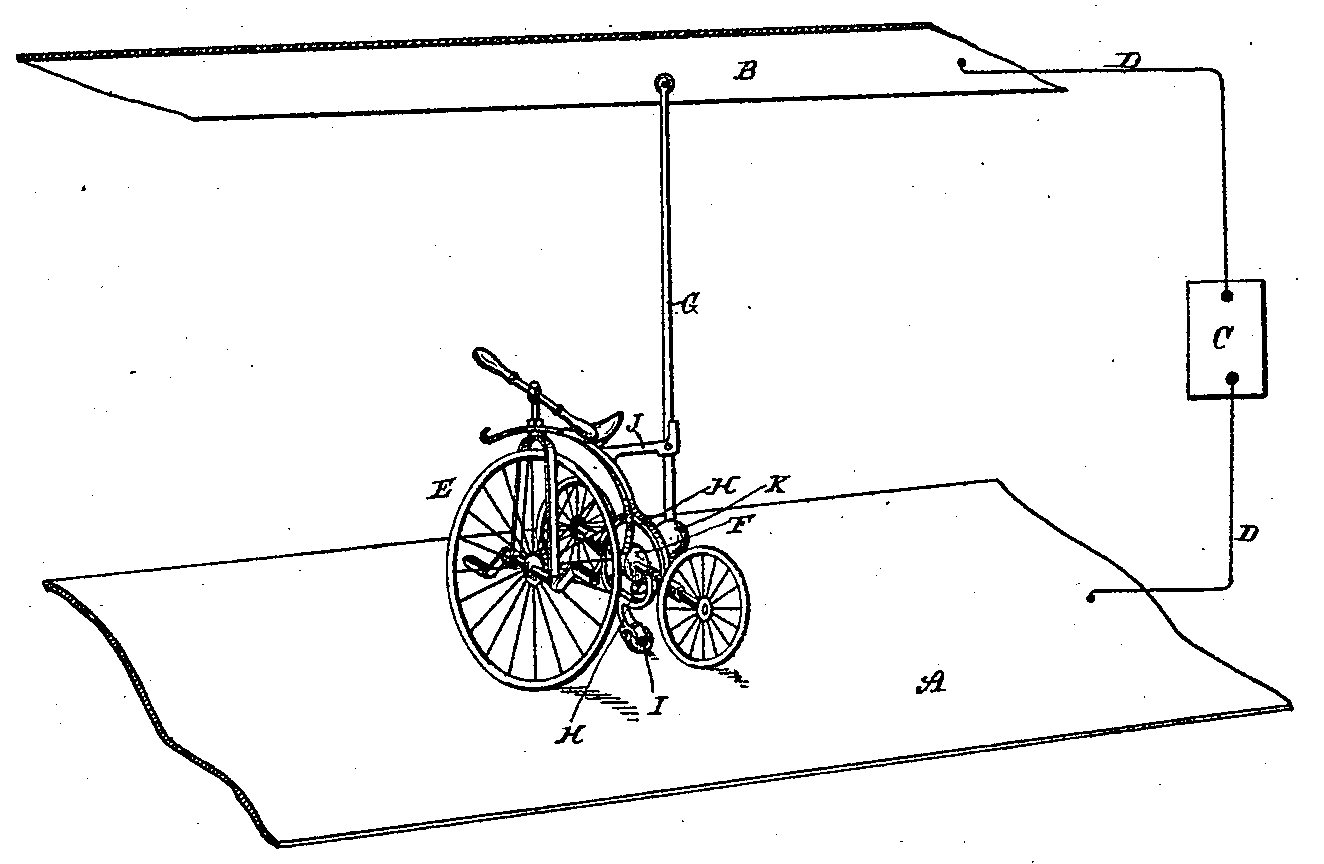

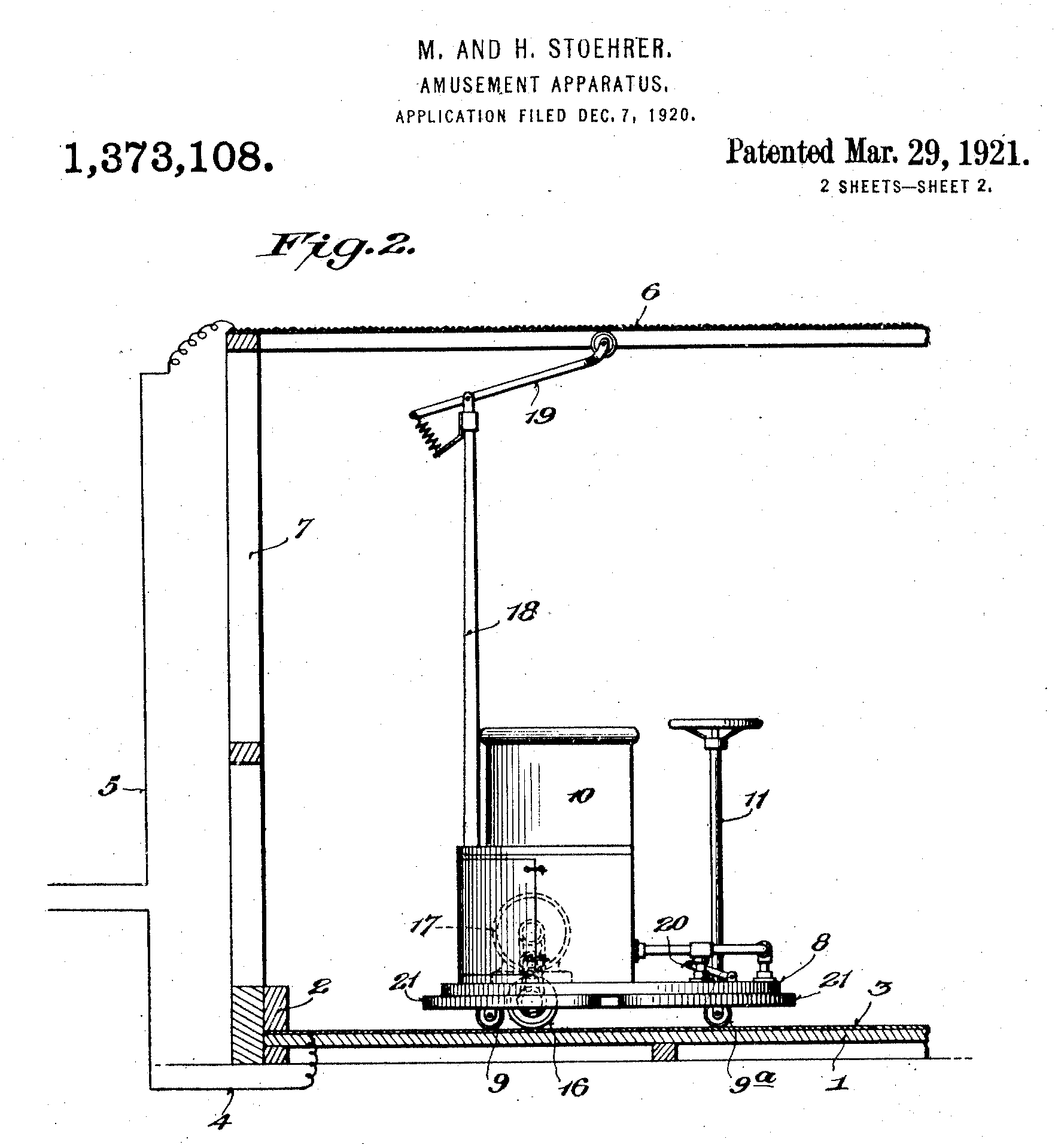

The romantic tree houses high up in the gnarled branches of giant chestnuts were decorated as dining rooms with wooden furniture. They were surrounded by a rustic railing and covered with a thatched roof. Some of them could accommodate up to ten patrons. The waiter hoisted the dishes and drinks up in large baskets using a rope and pulley system.

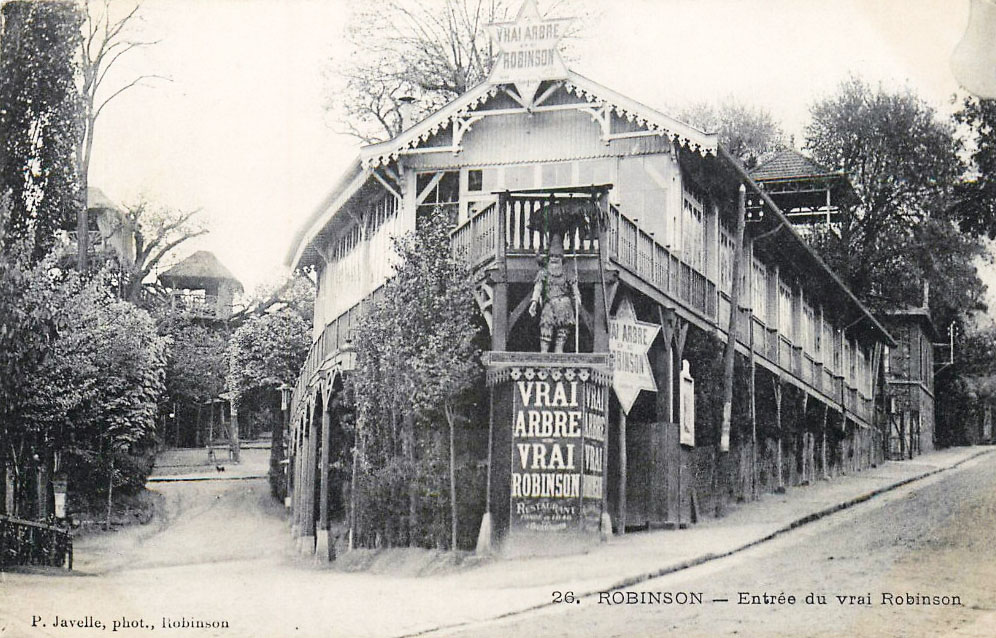

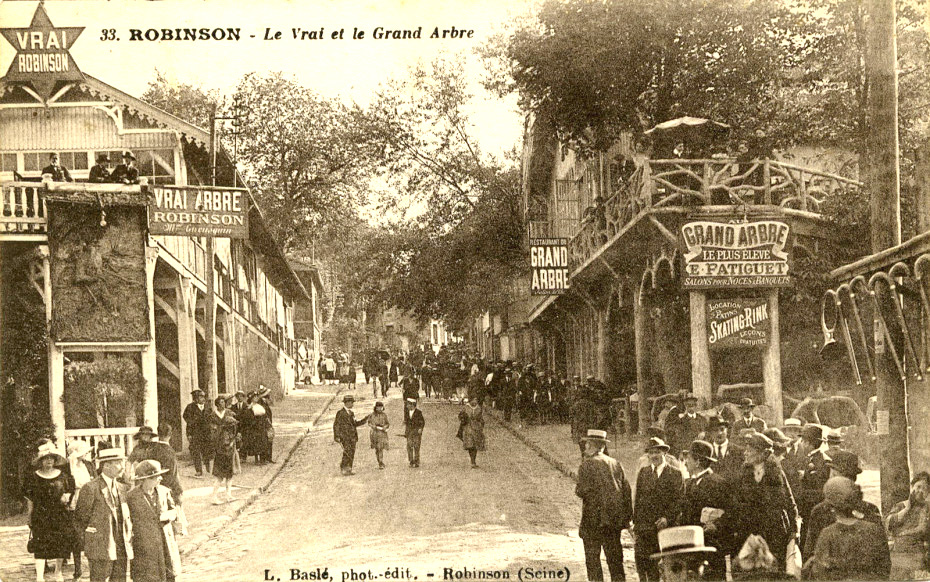

Soon copycats seeing the success of Au Grand Robinson were on the lookout for big trees in the surrounding area. As soon as they found one they started to build tree houses in it. At the beginning of the 20th century there were up to 30 establishments that had thus created their small hamlet of restaurants and taverns. Each claimed to have the most beautiful or the biggest tree. Hence, for authenticity’s sake Au Grand Robinson was renamed Le Vrai Arbre Robinson (The Real Robinson Tree).

Apart from its tree houses the Robinson guinguettes were known for donkey rides…

…swings,

… frolicsome bigophone parades,

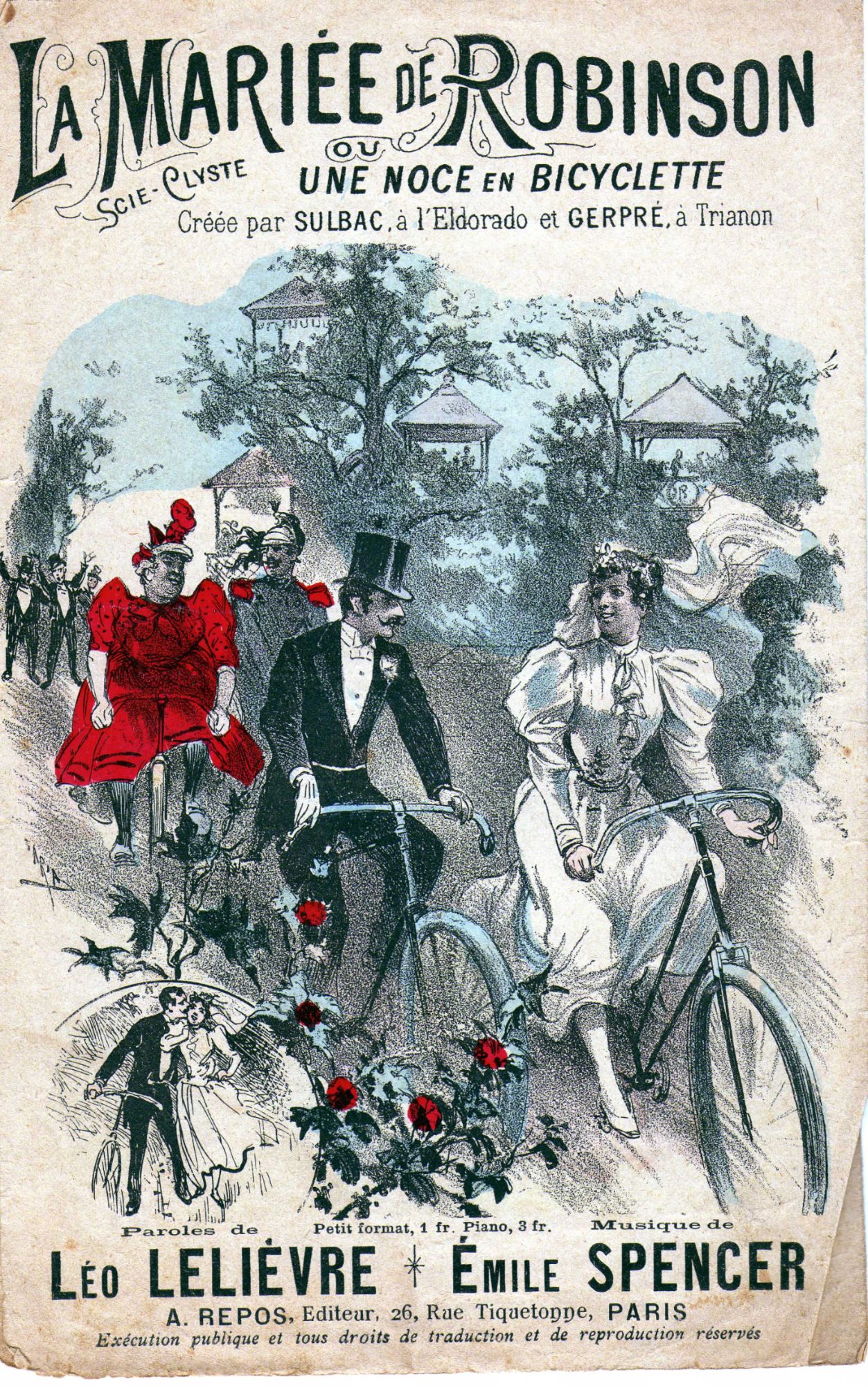

…and wedding parties.

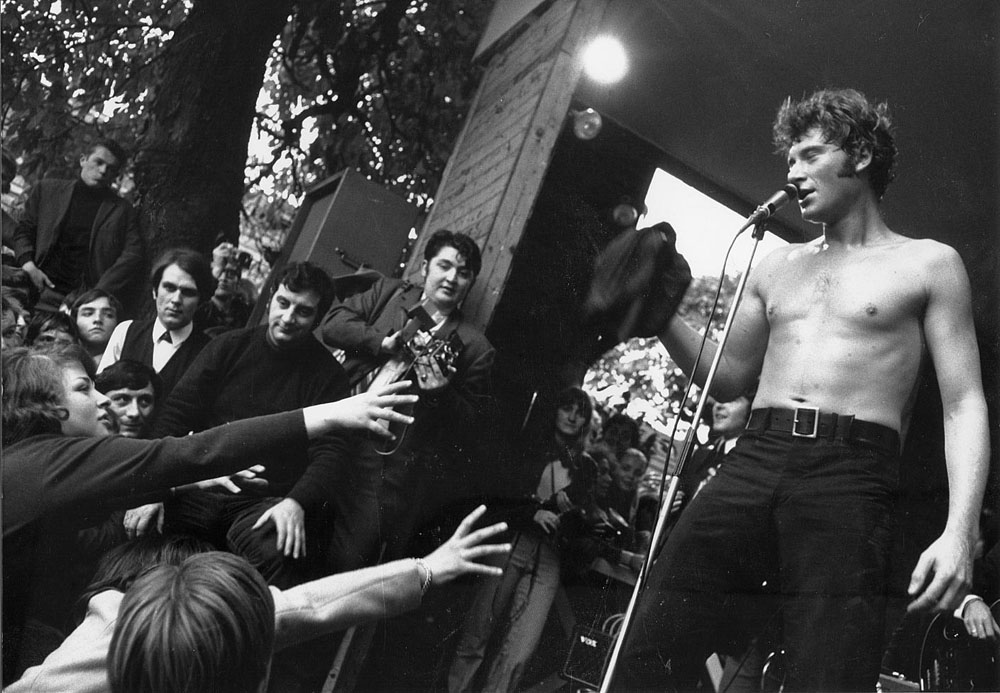

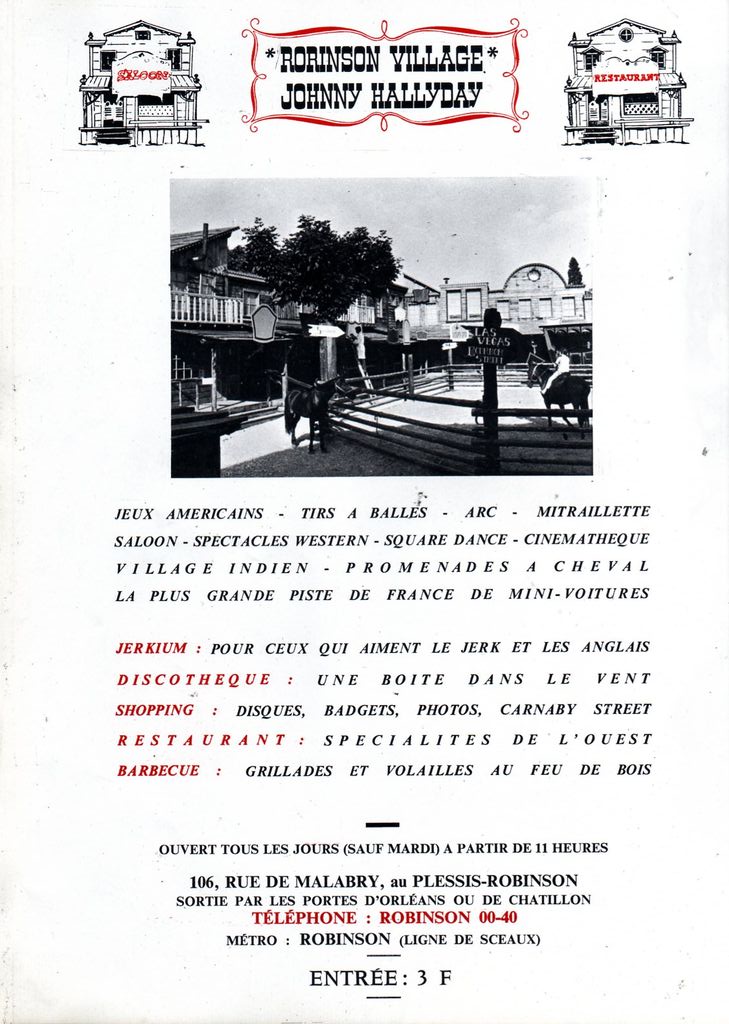

By the 1950s people had gotten tired of the Robinson guinguettes which started to close down one after the other. In 1966 the French rock singer Johnny Halliday together with a friend bought the original guinguette Le Vrai Arbre Robinson. Johnny (no need for his last name in France!) and his copain transformed the guinguette into a ranch and baptized it Robinson Village. The spirit of Robinson Crusoe was abandoned in favour of that of the American Wild West.

The small theme park boasted a mitraillette saloon, an Indian village, a Western Show, a disco and a Jerkium (where one could dance the Jerk).

Unfortunately the hope of the entrepreneurs to revive the spirit of the guinguette was smothered: Robinson Village had to close soon after it had opened.

Travelling back in time to 1966, Johnny sings his version of Black is black. Go Johnny go!

Further reading: “Mémoire de guingettes” by Francis Bauby, Sophie Orivel and Martin Pénet (Omnibus, 2003)