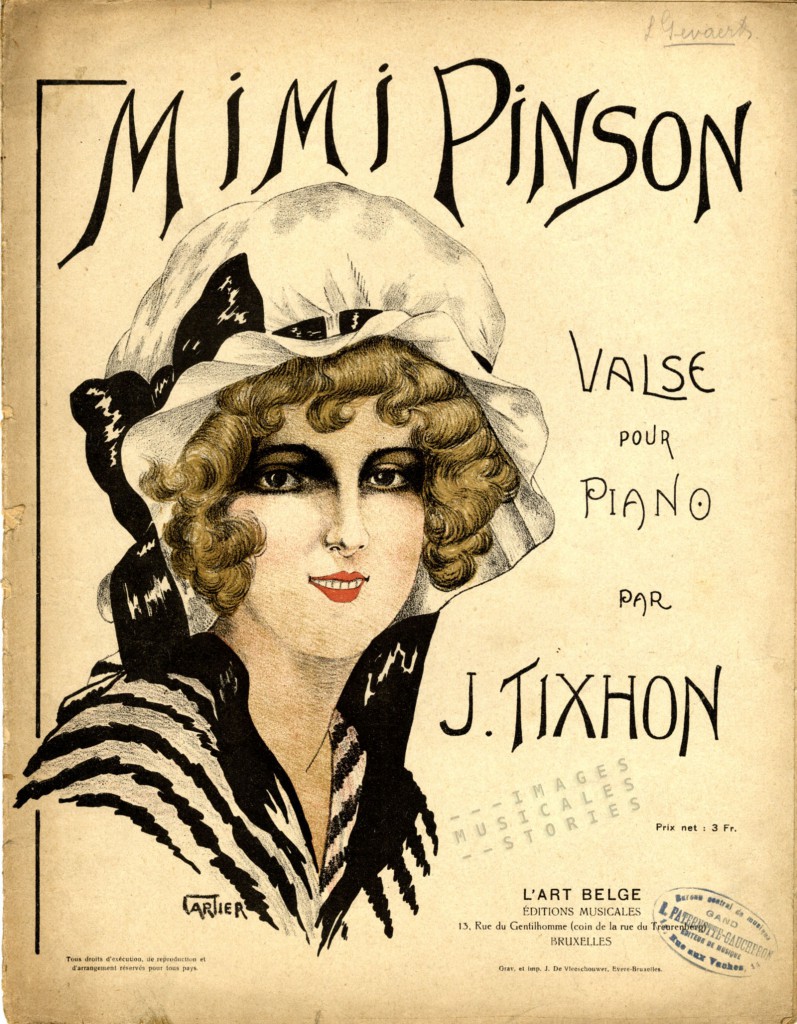

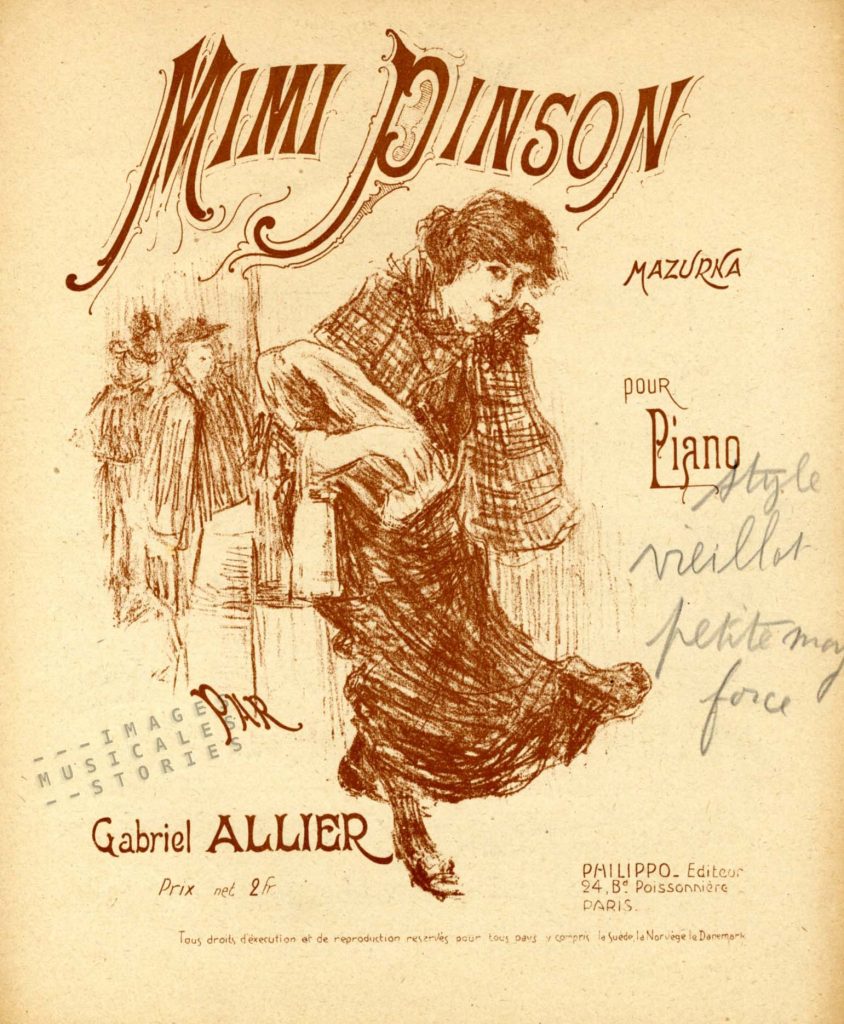

‘Mademoiselle Mimi Pinson: Profil de grisette’ is a novelette written by Alfred de Musset (1810-1857). A grisette is a coquettish young working woman employed as a seamstress, milliner’s assistant or shop helper. The word refers to the cheap grey (gris in French) fabric of the dresses these women originally wore.

In mid-19th century literature, the grisette became associated with the poor artistic and student subculture in the Latin Quarter: the Parisian bohemia. She is in her late teens or early twenties, living on her own in Paris, supporting herself by work. She is sexually independent, changing lovers frequently and of course posing for artists. She is the artists’ muse. She is frank and honest and subversive to mainstream bourgeois values. The grisette archetype was embodied by Fantine in Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables and by Mimi in La Bohème (see the stage photo and Metlicovitz’ illustrated sheet music cover in a previous post) from Puccini.

Gustave Charpentier (1860-1956) resurrected Mimi Pinson at the turn of the century. Charpentier was a composer of humble social backgrounds who became an idealistic socialist. He made a fortune with his opera Louise, a love story between grisette Louise and the young artist Julien. Listen to Renee Fleming’s captivating rendering of the aria Depuis le jour.

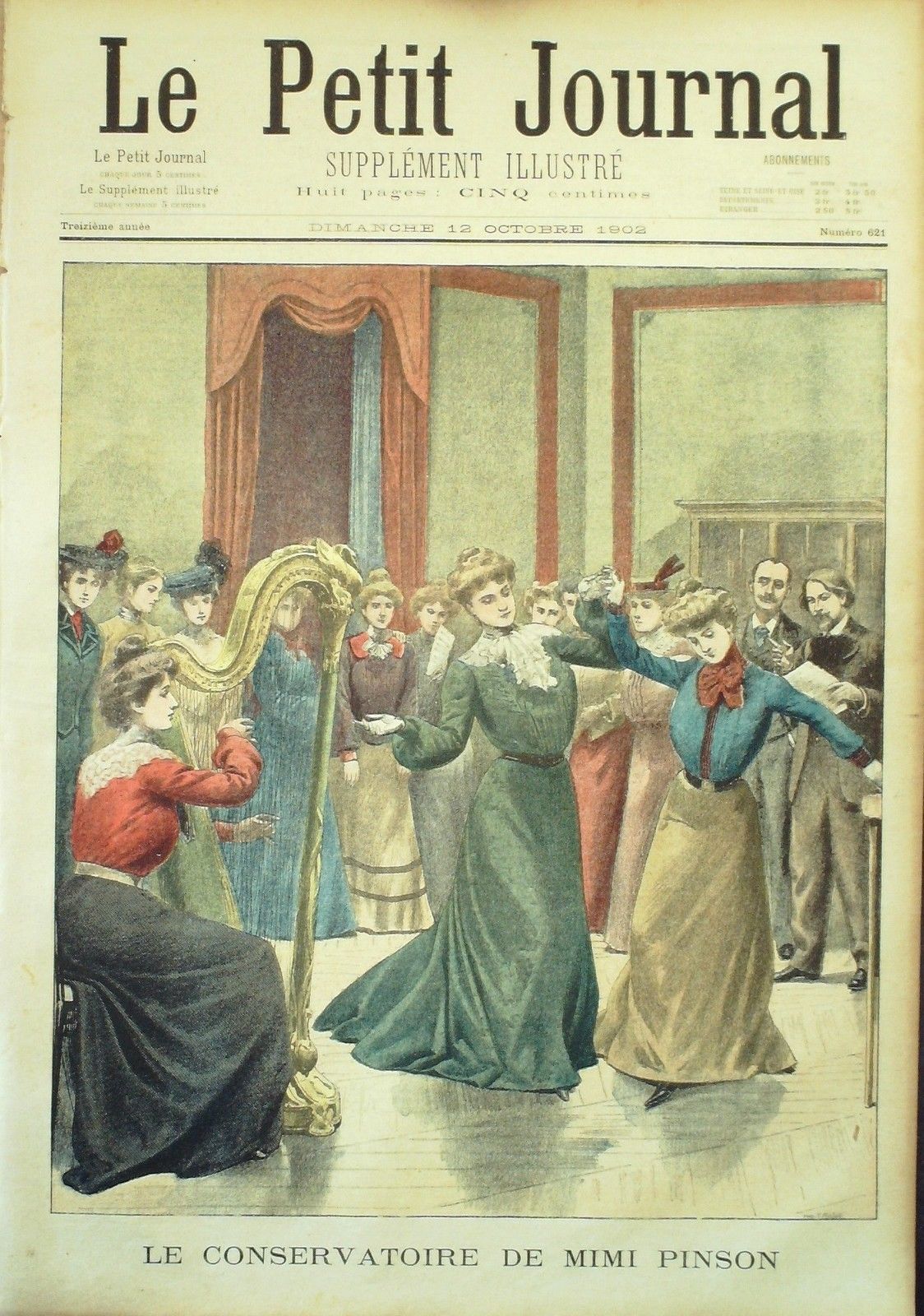

The success of the opera Louise provided the means for Charpentier’s charitable work. In 1900 he established the Parisian social project l’Oeuvre de Mimi Pinson named after Alfred de Musset’s heroine seamstress. Originally l’Oeuvre intended to give working-class girls the possibility to attend a theatre or an opera at least once a year. In 1902 it became the thriving Conservatoire Populaire Mimi Pinson.

The music school was sponsored by the piano manufacturing firm Pleyel and the music publisher Enoch. It provided free tuition by professionals for working women in Paris. Within three months Charpentier claimed 2.000 students. The classes were attended by women ranging from 15 years old to middle age, all of them unmarried. Charpentier saw the chanson populaire as a moral tool to educate the masses. The worker-students were taught elementary music, song, piano, harp, dance and pantomime.

Charpentier’s students performed all over France mostly in the service of a worthy cause. In all their spectacles, there was always a pantomime present in order to celebrate the ‘People’s Muse’ Mimi Pinson, represented by a local female labourer elected by her co-workers.

Although the Conservatoire Populaire Mimi Pinson was very successful many were opposed to it and warned that this artistic liberation might upset the social order. The young female workers should marry, do their appropriate work and make their hard-working husbands happy. Or as one paternalistic critic put it: “The theatre is encumbered enough with the untalented… without making these nice little girls drop their needles”.

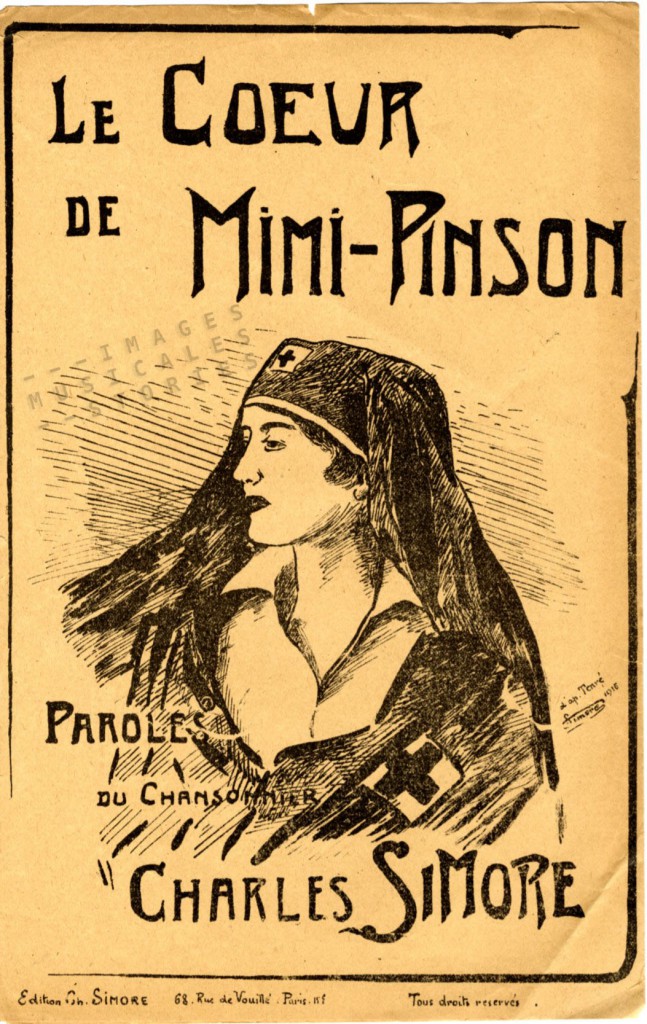

During the First World War many of the Mimi Pinsons became symbols of feminine self sacrifice. They joined the war effort as workers and were trained to become nurses. The Conservatoire Populaire Mimi Pinson became an auxiliary to the Red Cross.

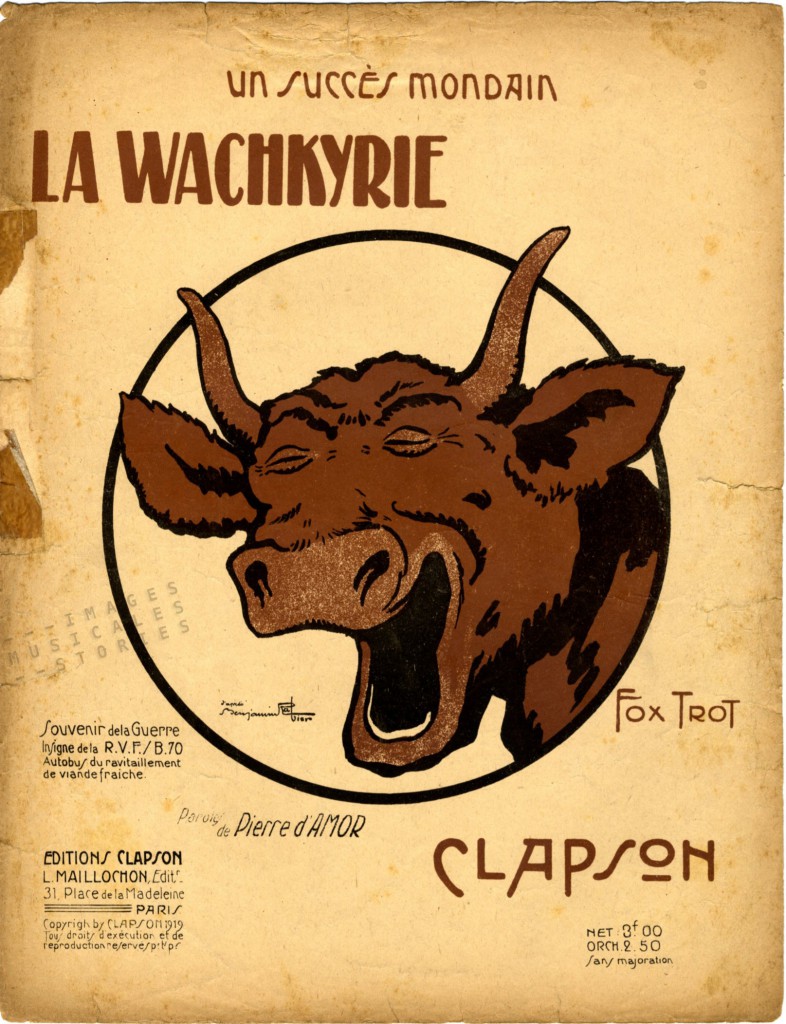

Other Mimi Pinsons made patriotic tricolour rosettes or cockades for charity from 1915 to 1920. These were exposed and sold for the benefit of the soldiers. The exhibitions were sponsored and supported by the major fashion houses and shops in Paris. Their female personnel also actively participated in the making and presentation of the cockades.

Henri Goublier recounted this social and patriotic work of the Mimi Pinsons into the war-related operetta La Cocarde de Mimi Pinson (The cockade of Mimi Pinson). The first act, set in a textile manufacture in Paris, shows female workers producing cockades, the blue-white-red national symbols, as “love gifts” for the soldiers at the front.

In 1919 the majority of the Mimi Pinsons, being regularly informed about their rights as labourers, joined the call for women’s suffrage.

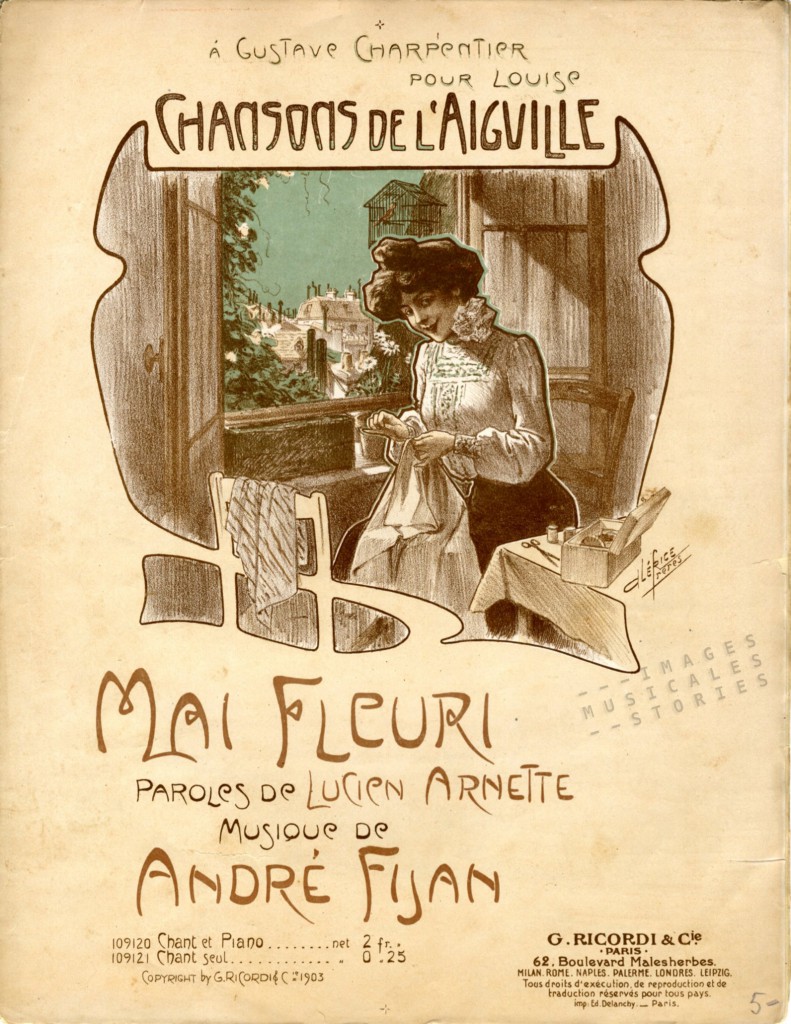

During the first quarter of the 20th century Mimi Pinson was a popular symbol in France. She was represented living in an attic room with her animal friend a finch (pinson is the French word for a common finch). Clérice used the same symbolism to illustrate the cover of Chansons de L’ Aiguille (Songs of the Needle) composed by André Fijan and dedicated to Gustave Charpentier and his opera Louise.

During the first quarter of the 20th century Mimi Pinson was a popular symbol in France. She was represented living in an attic room with her animal friend a finch (pinson is the French word for a common finch). Clérice used the same symbolism to illustrate the cover of Chansons de L’ Aiguille (Songs of the Needle) composed by André Fijan and dedicated to Gustave Charpentier and his opera Louise.

In 1958 Mimi Pinson got a new but short-lived reappearance with a film of the same name by Robert Darène.

For further reading: Gustave Charpentier and the Conservatoire Populaire de Mimi Pinson by Mary Ellen Poole.