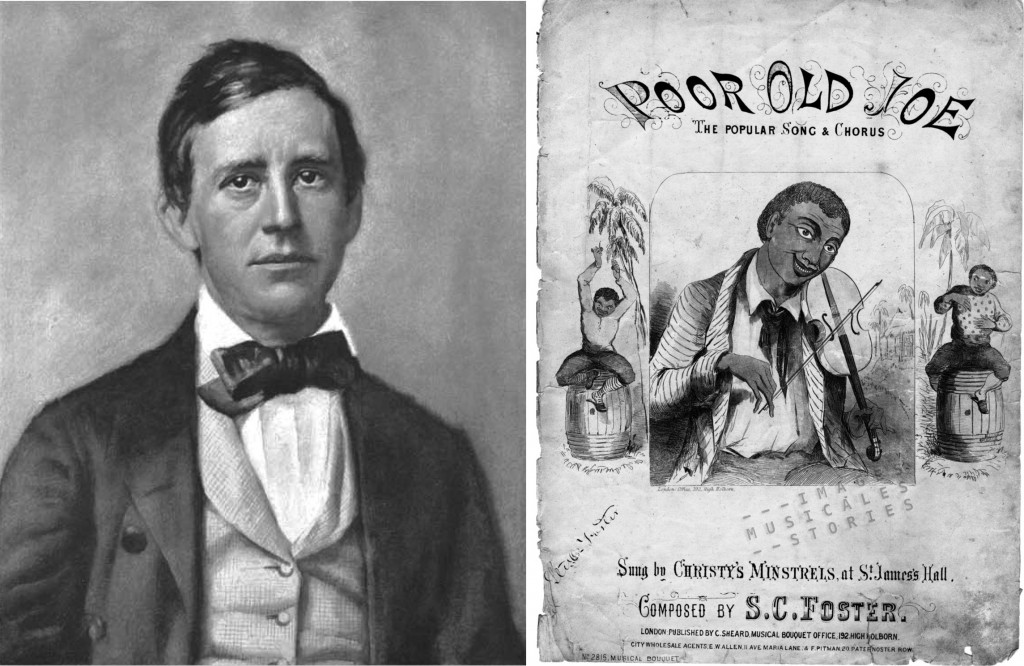

‘Oh! Susannah!‘ is a milestone in American popular music. After its launch and first publication in Pittsburgh, it sold more than 100.000 copies. Later numerous minstrel troupes performed and registered the song: from 1848 until 1951 it was copyrighted and published no less than 21 times! What we show here is the illustrated British sheet music published by Duncombe & Moon (Holborn London, s.d.).

Probably due to its country-wide popularity ‘Oh! Susannah!‘ became the unofficial theme of the Forty-Niners (1849 goldseekers). This success, together with a royalty rate of two cents per copy of sheet music sold, makes composer Stephen Foster commonly regarded as America’s first professional songwriter.

‘Oh! Susannah!‘ tells the story of a man travelling from Alabama to Louisiana in search of his love. His instrument accompanies him on the road, which brings us to today’s topic: the banjo.

About the history of the banjo we found the following condensed summary on The Bitter Southerner website.

- The handmade gourd instruments that would become the modern banjo originated in West Africa;

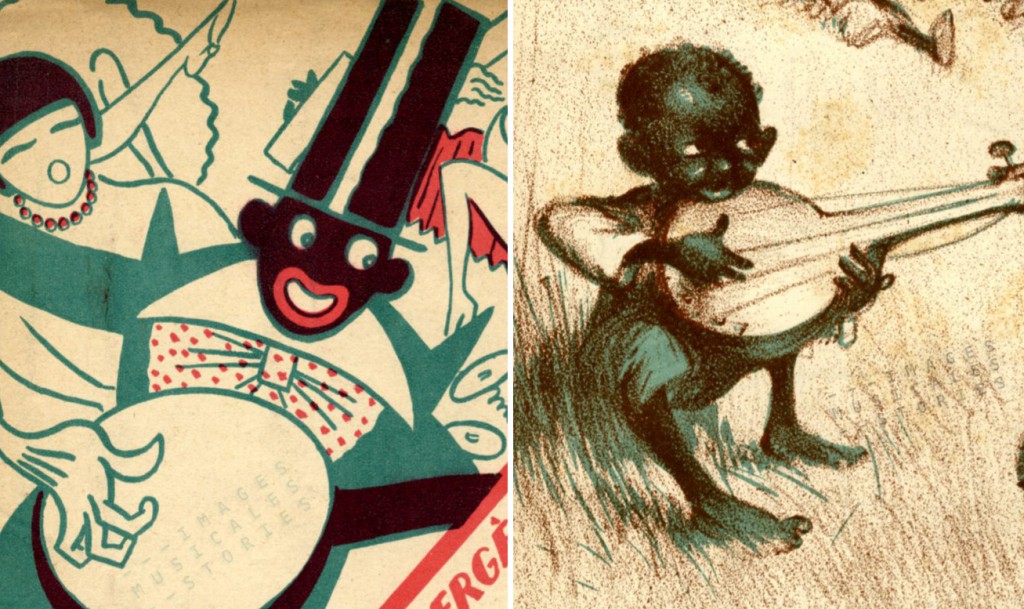

Details from sheet music covers. Left a banjo player by Gaston Girbal, right a very young musician by Poulbot. - Enslaved Africans carried the ‘banjar’ and its music to North America by way of the Caribbean;

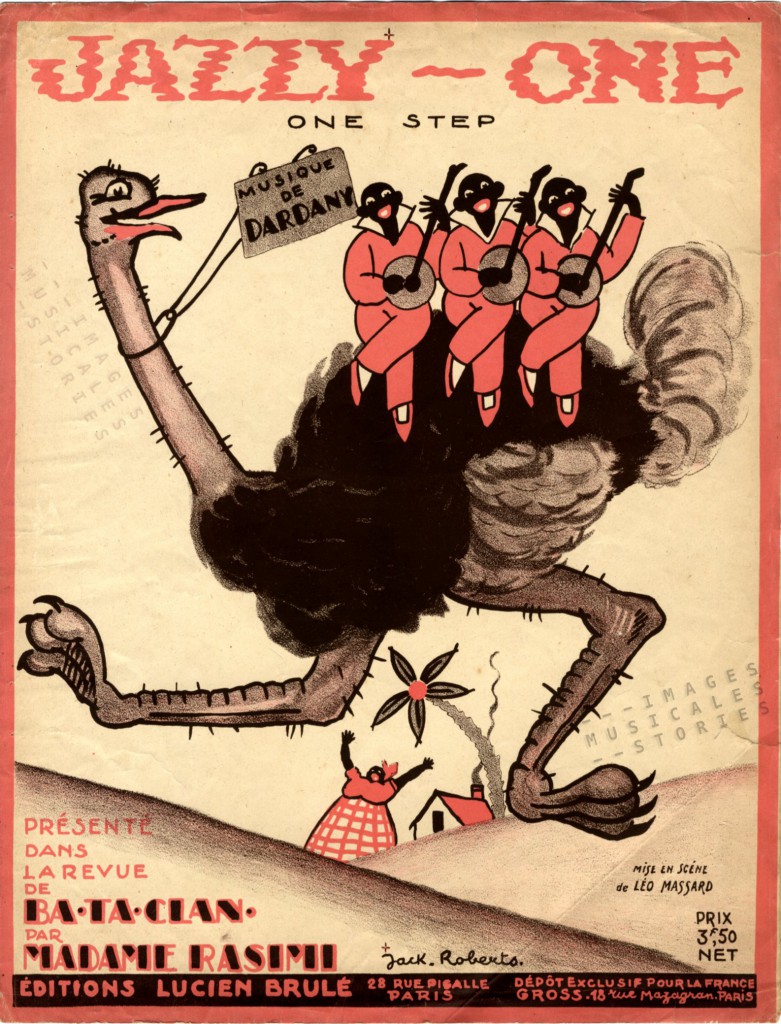

‘Jazzy-One (One-step de l’autruche)‘, by Dardany, illustrated by Jack Roberts (Editions Lucien Brulé, Paris, 1923). - Traditional string music (and the banjo itself) was appropriated from slave culture and was spread into the greater American popular culture through minstrel shows and blackface performances;

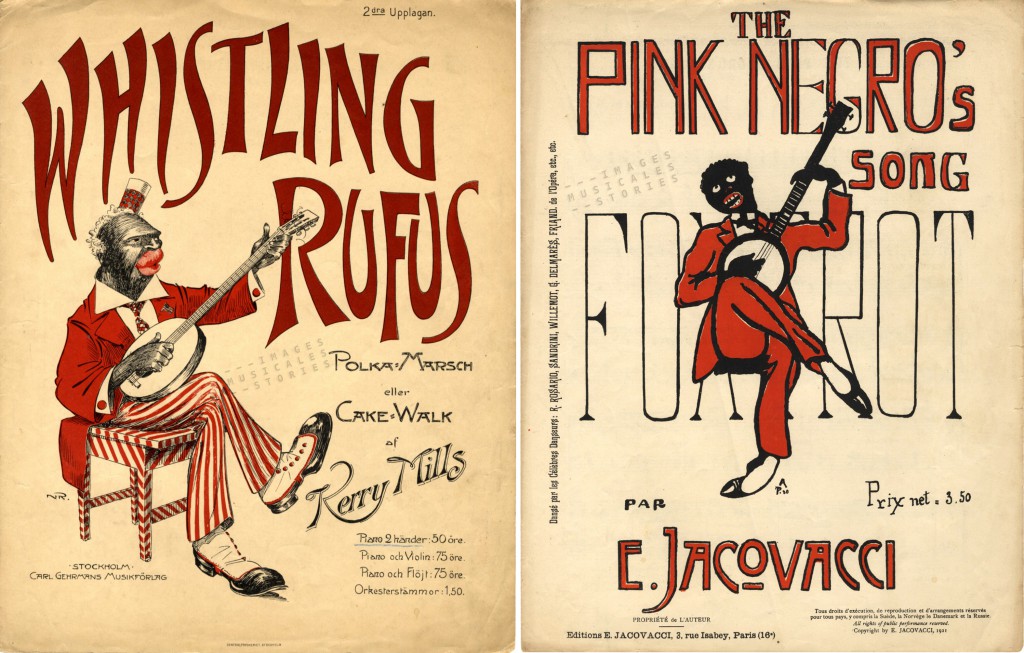

Left: ‘Whistling Rufus‘ by Kerry Mills (Gehrmans Musikförlag, Stockholm, 1904). Right: ‘The Pink Negro’s Song‘ by Edouard Jacovacci (Paris, 1921) - The banjo was popularized throughout the United States and Europe by white performers, with various regional playing styles emerging and evolving simultaneously – from the rhythmic role the banjo played in traditional New Orleans jazz to the fingerpicking sound of bluegrass that bloomed in the Appalachian mountains, among many others.

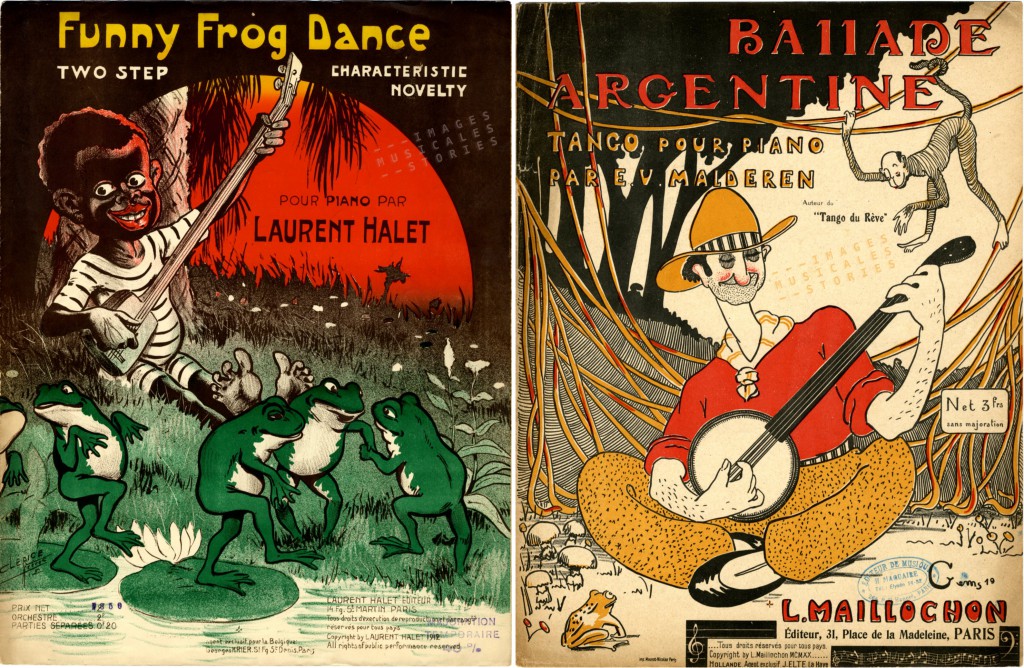

Two sheet music covers of banjo players in the swamp or jungle. Left: ‘Funny Frog Dance‘ by Laurent Hallet, illustration by Clérice frères,1912. On the right: ‘Ballade Argentine‘ by E.V. Malderen, illustrated by Gems, 1920.

Essentially the instrument is a drum with a long neck attached for securing a set of strings. The strings are supported by a bridge that sits on the drum membrane. The bridge vibrates up and down as the drum resonates. So there are effectively two different periodic changes to the tension of the string at the same time: (1) the string’s natural frequency when picked, plucked or struck, and (2) the drum’s frequency of vibration. It is this modulating frequency that produces the banjo’s bright metallic timbre. (This is all better explained by Nobel prize-winning physicist David Politzer in ‘The Secret of the Banjo’s Twang‘.)

The typical twangy sound of the banjo, its limited artistic… eh… rather plain or monotonous resonance, together with its rural background and folky/country/traditional connotation, probably gave rise to numerous jokes (aka banjokes) on the instrument, the ‘music’ and its players. Here we go.

- How many strings does a banjo have?

Five too many…

Striking caricatures of banjo players. Left: ‘Dansez le Shimmy‘ by L. Halet and V. Telly, illustrated by G. Girbal (Paris, 1921). Right: ‘Jim‘ by D. Rulli and C. Bruno, illustrated by Monni (Rome, 1929). - No matter how much you tune it–it will still sound like a banjo.

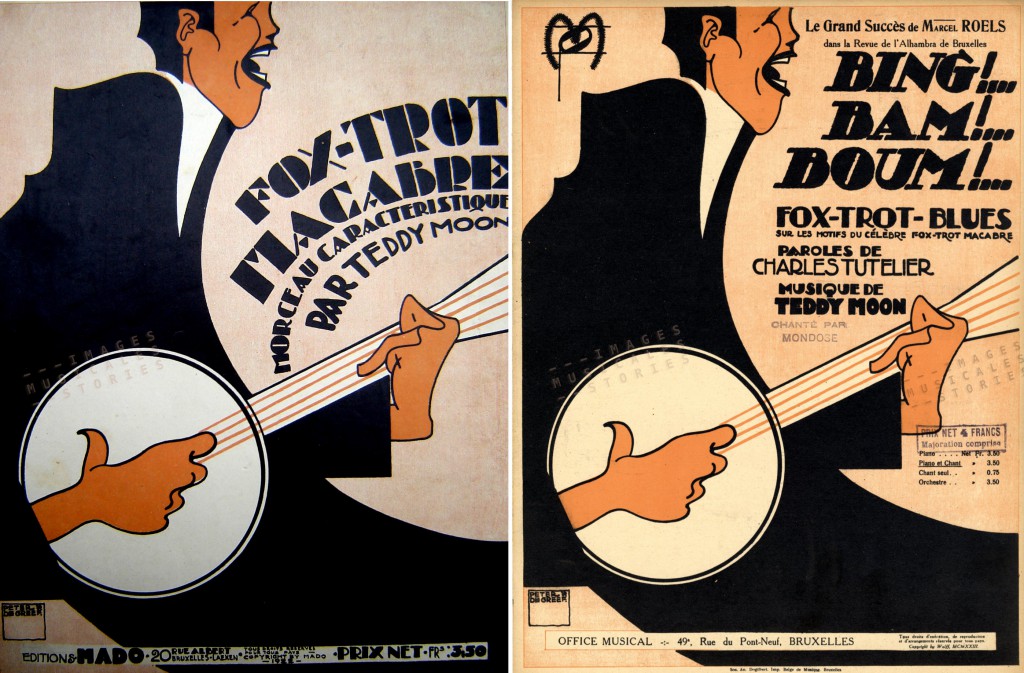

Two layouts of Peter Degreef’s fantastic sheet music cover. Left: ‘Fox-Trot Macabre‘ by Teddy Moon (Mado, Bruxelles, not in our collection); on the right: ‘Bing! Bam Boum!‘ by Teddy Moon and Charles Tutelier (Office Musical, Bruxelles, 1923). - Why was the banjo player standing on the roof? Because they told him the drinks were on the house.

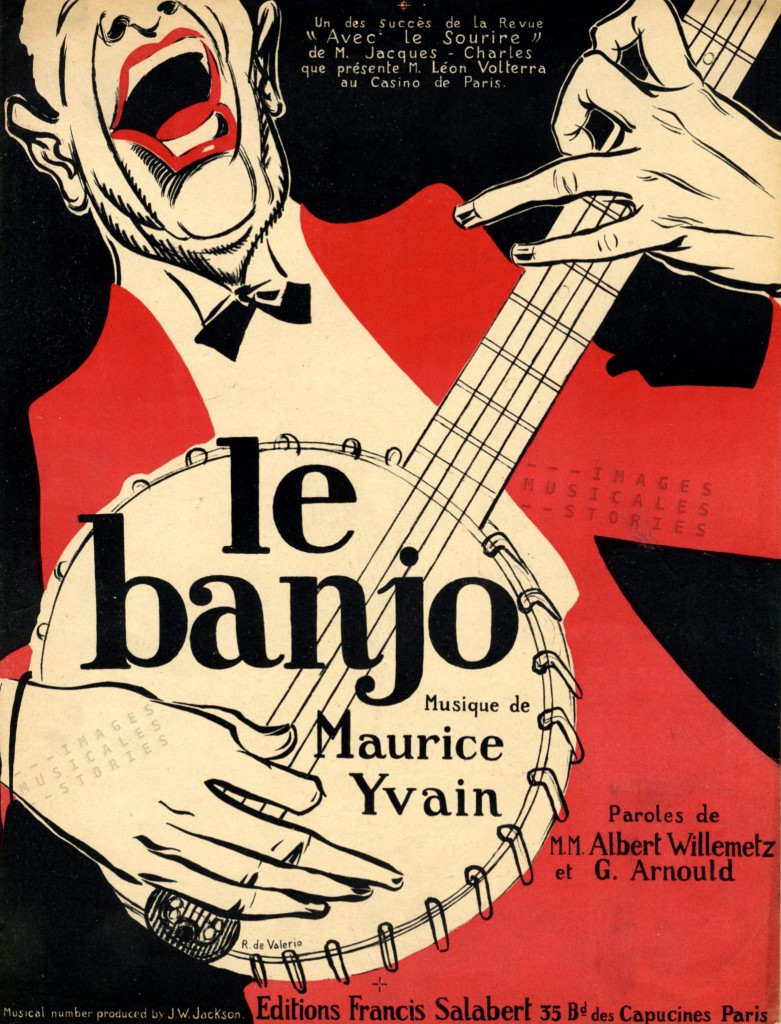

Four sheet music covers by De Valerio: ‘Whistle away your blues‘ (1926), ‘Wagneriana‘ (1922), ‘On m’a!‘ (1924) and ‘By the Campfire‘ (1919), all published by Francis Salabert, Paris. - How do you make a banjo player slow down?

Put some sheet music in front of him.

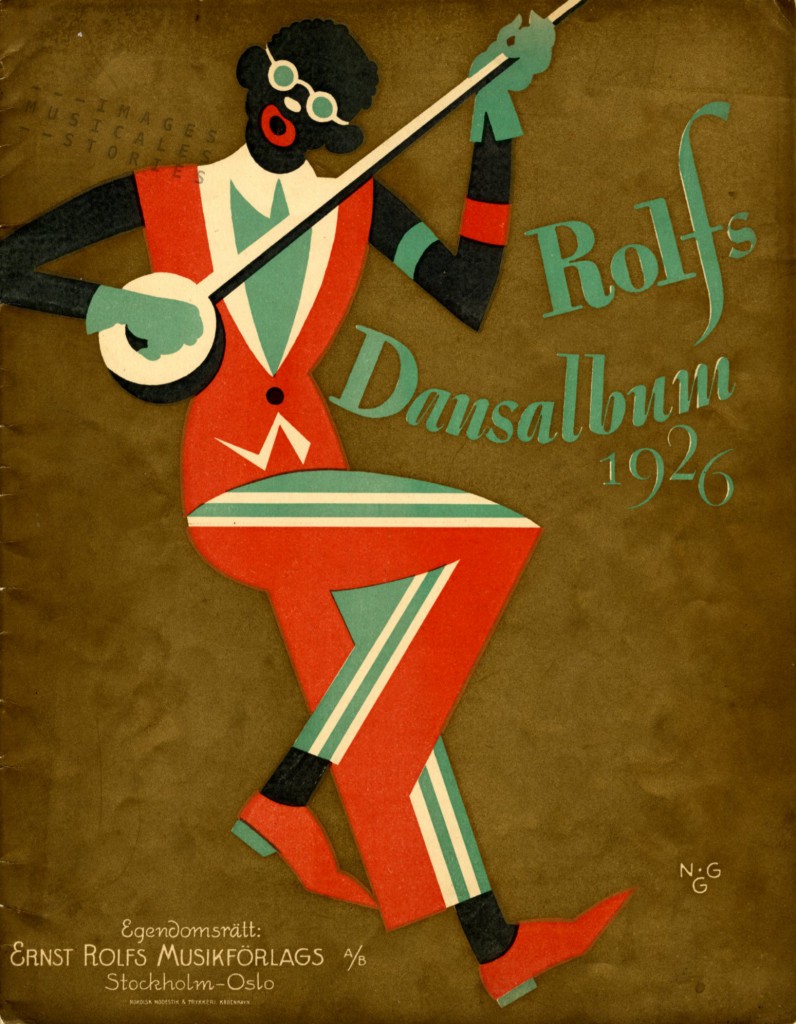

‘Rolfs Dansalbum 1926‘ illustrated by N.G. Granath (Ernst Rolfs Musikförlags, Stockholm, 1926).

- Like the banjo itself, whose twang can clear clogged sinuses and remove stubborn wallpaper, the mountain music is an acquired taste.

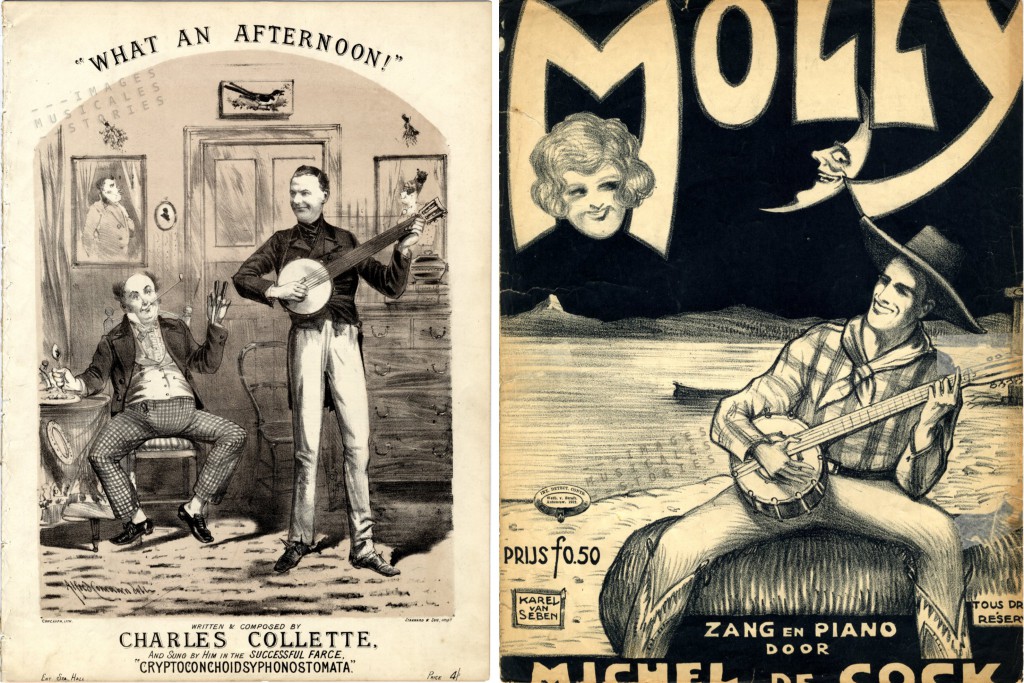

A banjo brings gaiety. Left: ‘What an Afternoon!‘, by Charles Collette, cover illustration by Alfred Concannen (unknown publisher, s.d.). Right: ‘Molly‘ by Michel De Cock, illustrated by Karel Van Seben (Amsterdam, s.d.)

- What is the range of a banjo? About 10 meters if you throw it hard enough.

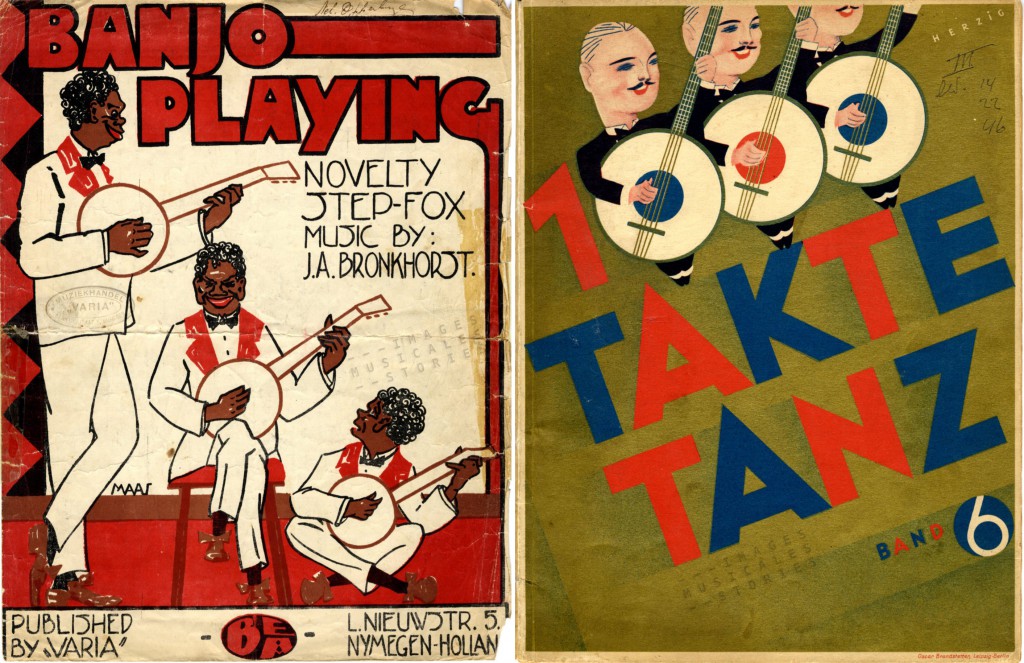

Trios of banjo players. Left: ‘Banjo Playing‘ by J.A. Bronkhorst, illustrated by Maas (Varia, Nijmegen, s.d.). Right: ‘1000 Takte Tanz – Band 6‘, illustrated by Herzig (Berlin, 1931). - Don’t tell my mom I’m a banjo player.

She thinks I’m a piano player in a whorehouse.

Banjo playing Pierrot and Harlequins. Various details from sheet music covers illustrated by Lopresti (s.d.), Louis Oppenheim (1912) and Loris Riccio (s.d.). - How can you get six banjo players to play in harmony?

Only give one of them a banjo.

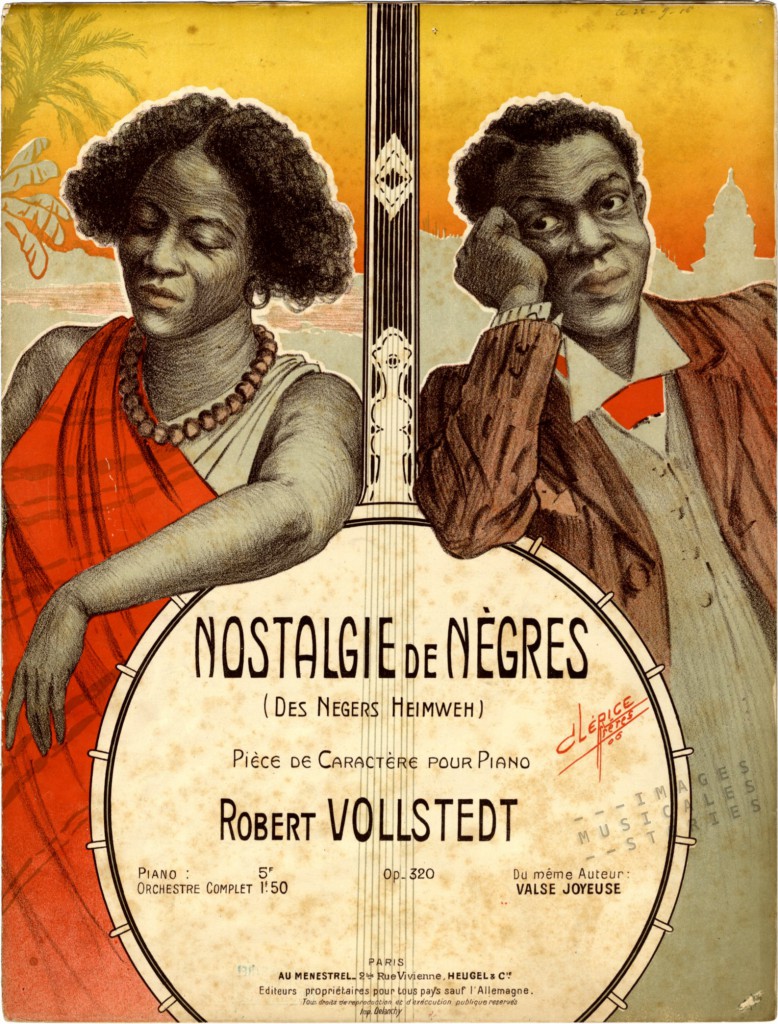

‘Nostalgie de Nègres (Des Negers Heimweh)‘ by Robert Vollstedt, illustrated by Clérice frères (Au Ménestrel, Paris, 1906). - Did you hear that they’ve isolated the gene for banjo playing?

It’s the first step to a cure.

A jumble of banjo elements from our Illustrated Sheet Music collection. - Banjo player: “When I die, I want to leave the world a better place.”

Guitar player: “Don’t worry, you will.”

Frantic banjo dancing. Left: ‘Johnson‘ by Rulli and Cherubini, illustrated by Monni (Casa della Canzone, Rome, s.d.). Right: ‘Banjo‘ by David Ottoson, illustrated by D. Sim (Anderssons Musikforlag, Malmö, 1914). - What’s the fastest way to tune a banjo?

With wire cutters.

Relentless banjo happiness. Top left: ‘Banjo Song (Original Jazz-Band)‘ by Frank Stafford, illustrated by W. Ortmann (Berliner Bohème Verlag, 1921). Top right: ‘Her, me and the Charleston‘ by José Lucchesi, illustrated by Dola (?) (Max Eschig & Cie, Paris, 1927). Bottom left: ‘Flickan Därhemma‘ by John Charles, illustrated by Lindström (Derwin & C° , Stockholm, 1930). Bottom right: ‘Cupidon (Alone at last)‘ by Ted Fiorito, illustrated by F. Loris (Publications Francis-Day, Paris, 1925). - A man walked into a bar with his alligator and asked the bartender, “Do you serve banjo players here?”

“Sure do,” replied the bartender.

“Good,” said the man.

“Give me a beer, and I’ll have a banjo player for my ‘gator.”

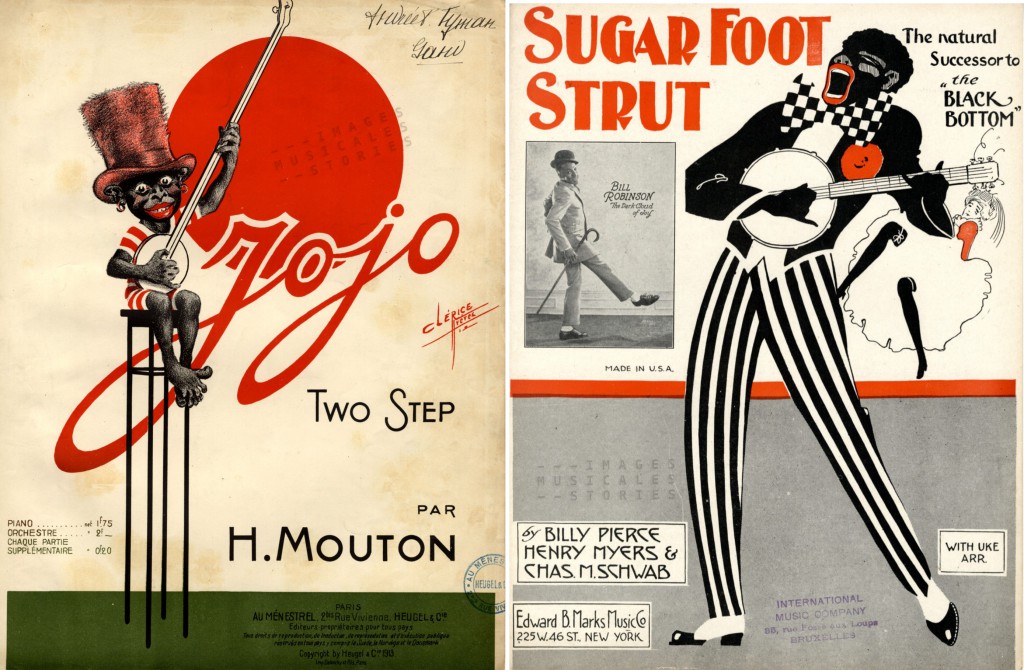

Left:’Jojo‘ by Hubert Mouton, illustrated by Clérice frères (Au Ménestrel, Paris, 1913). Right: ‘Sugar Foot Strut‘ by Pierce, Myers and Schwab, illustrator unknown (Marks Music Co., New York, 1927).

(all jokes from Phillip Mann’s Banjo Tab Collection and Bluegrass Information Site)

Enough, enough! Stop the stupid jokes. It’s time for serious playing by 8-year old Jonny Mizzone: