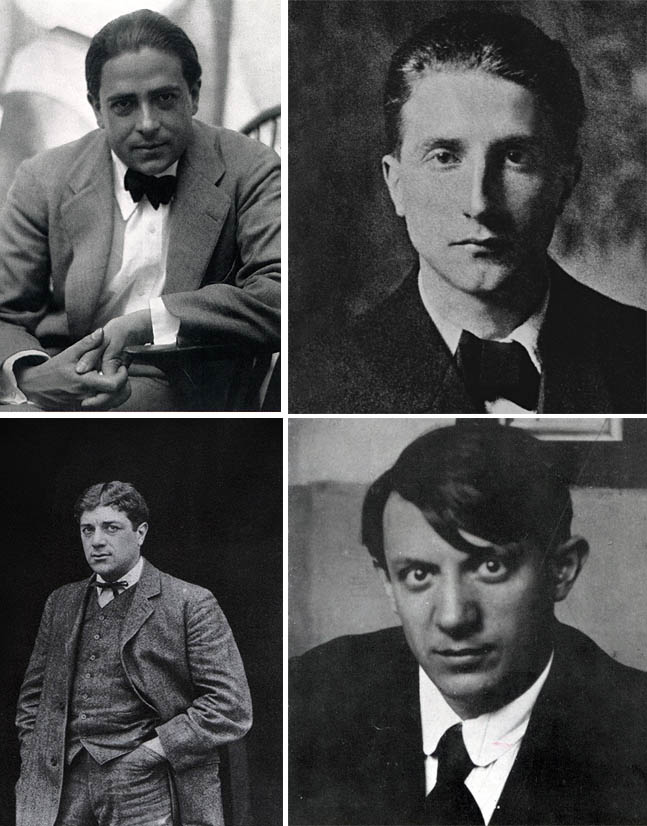

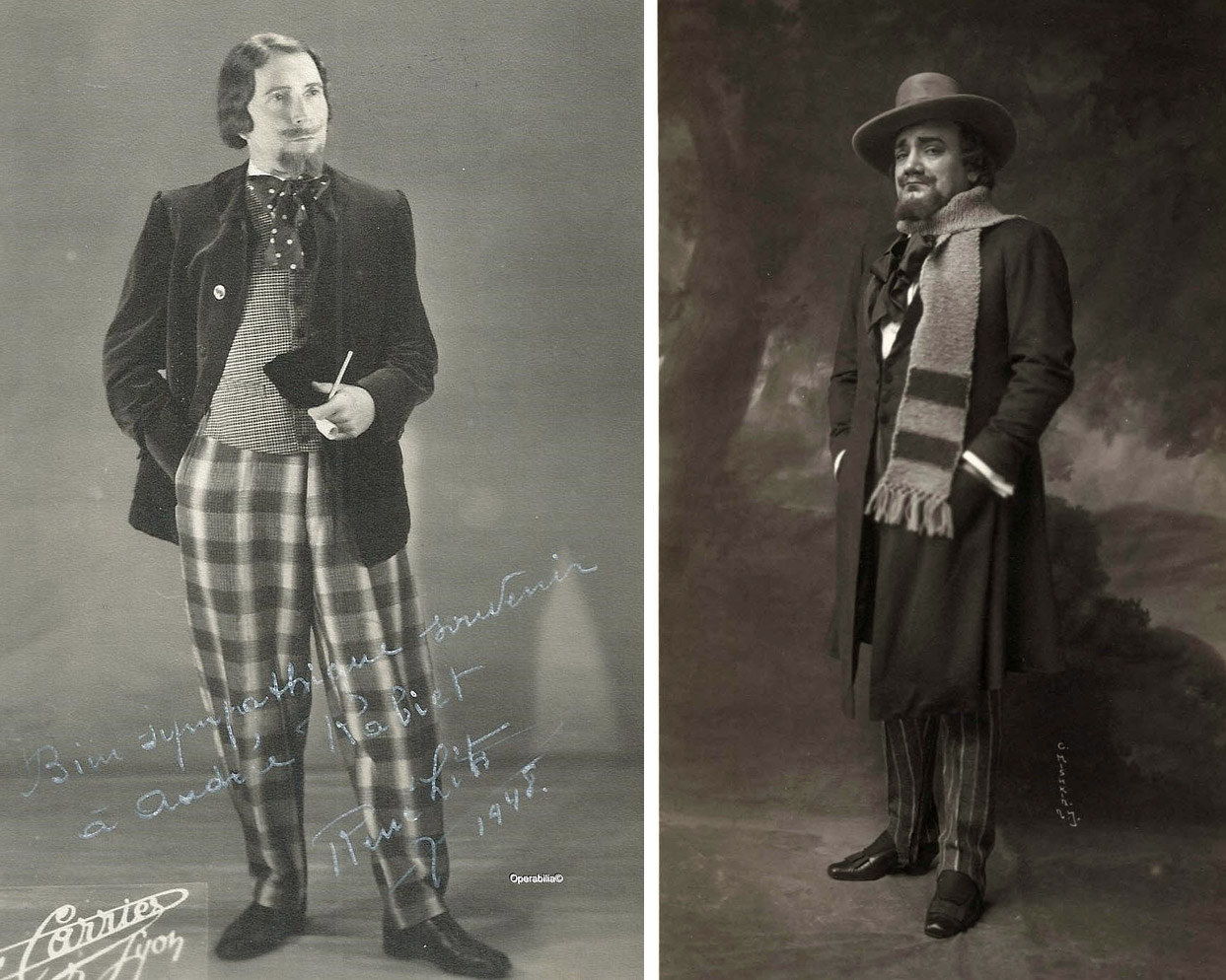

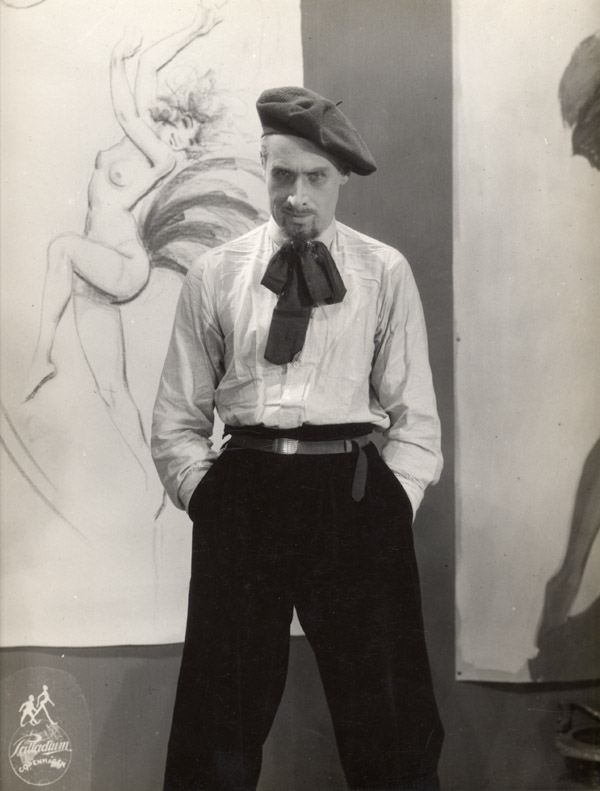

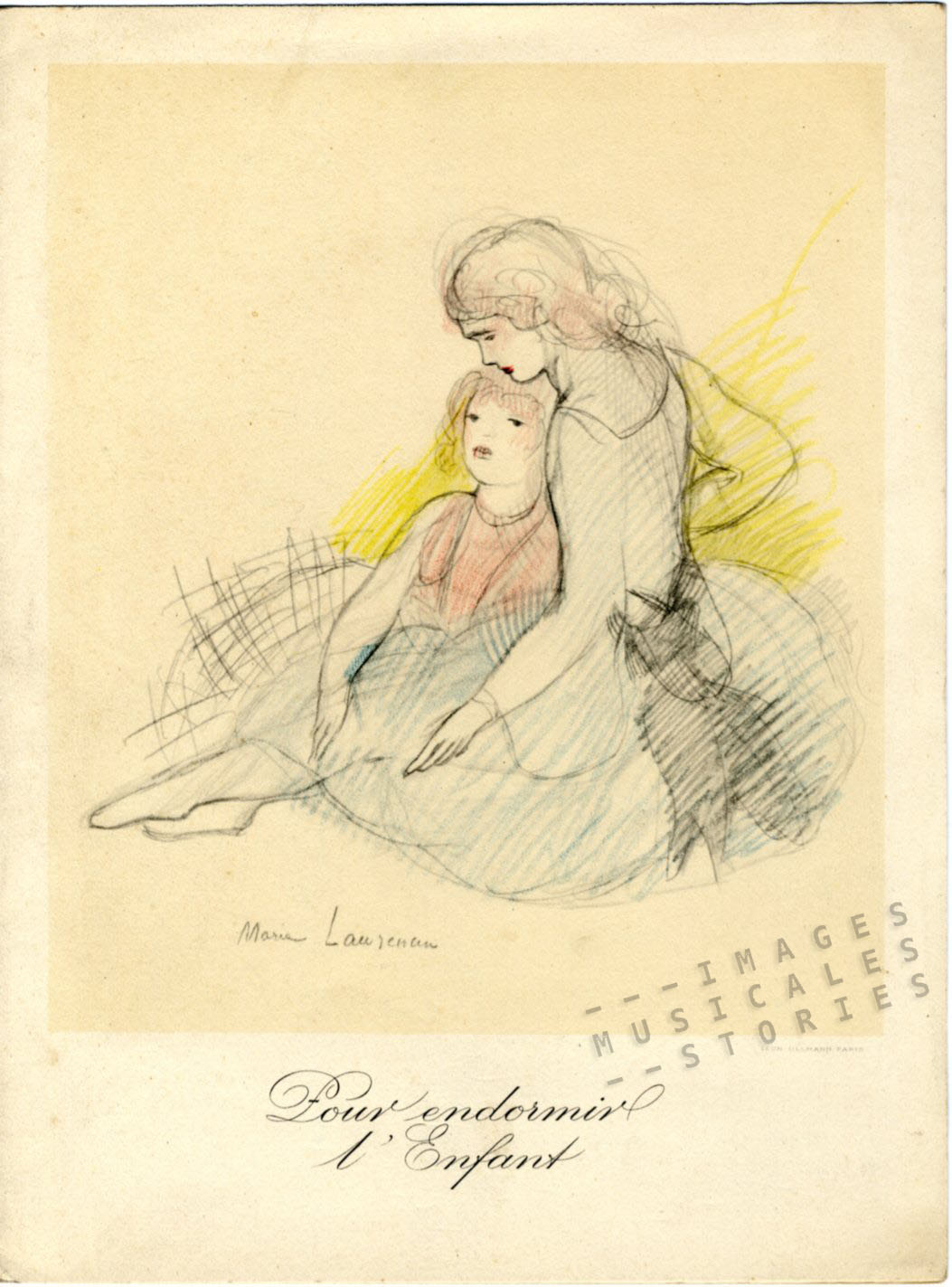

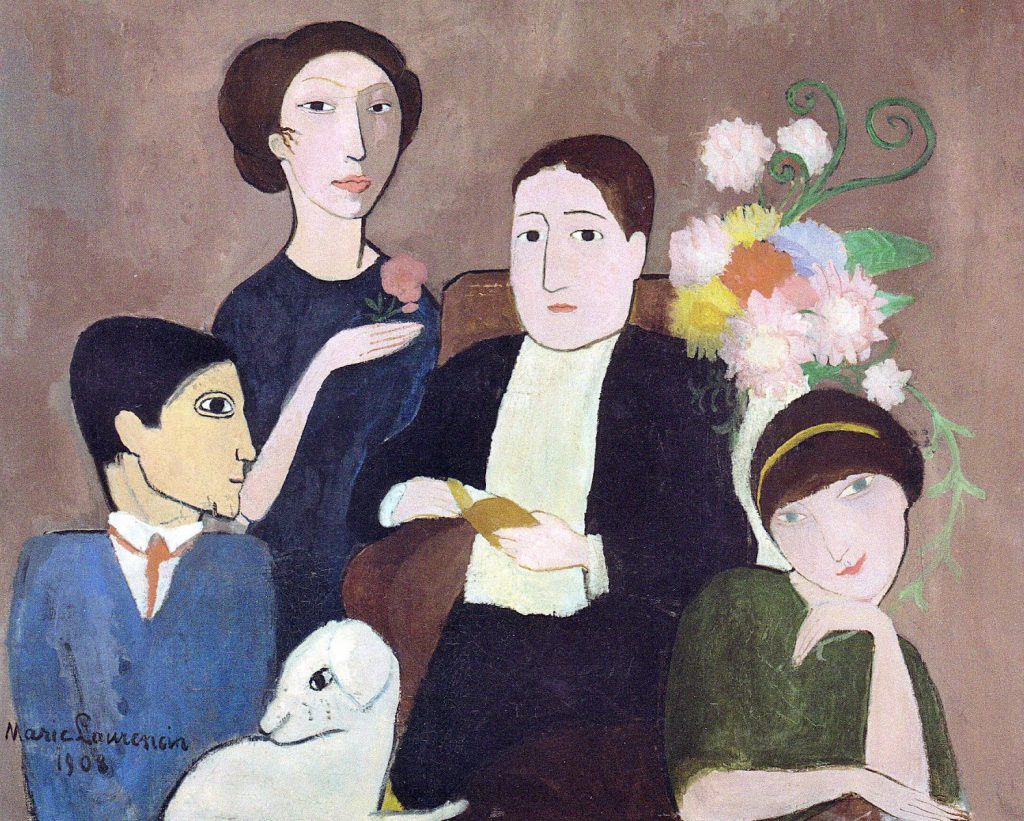

This gentle cover of two dreamy young girls in typical pastel colouring and soft shading is the only one in our collection illustrated by Marie Laurencin (1883-1956). She was a painter and got acquainted with the artists who took up residence in the Bateau-Lavoir, amongst them Max Jacob, Picasso and Bracque.

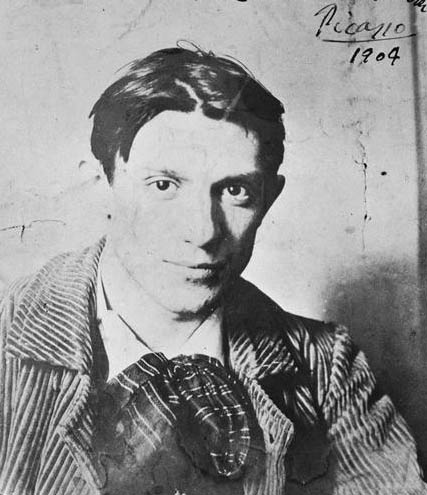

In 1907 Picasso introduced Marie Laurencin to his friend the poet Guillaume Apollinaire and they became romantically involved. Their passionate affair was burdened by Apollinaire’s alcohol abuse, his jealousy and violence. It lasted until 1912 and had already started to crumble the year before when Apollinaire was wrongly suspected of having had a hand in the theft of the Mona Lisa.

Just like Marie Laurencin, Apollinaire had been raised by a single mother. His father disappeared very early on and his mother travelled with her children from hotel to hotel, frequenting the European casinos. The cosmopolitan Apollinaire spoke five languages and was exceptionally cultivated. The poet scraped a living as a clerk in different places. While working for an investor’s chronicle Guide du Rentier he befriended Honoré-Joseph Géry Pieret a scoundrel born in Belgium who was sacked from the chronicle for attempted blackmail and would at some time work as Apollinaire’s personal secretary. In 1907 Géry Pieret stole two prehistoric Iberian sculptures from the Louvre and sold them to Picasso.

Making light of it Géry Pieret allegedly once said to Marie Laurencin: “I am going to the Louvre, Madam, do you need anything?” Picasso, who may have commissioned the theft himself, used the sculptures for his famous masterpiece Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907).

In May 1911, after some adventures abroad about which he entertained Apollinaire through letters, Géry Pieret returned to Paris. The poet lodged him in his kitchen in exchange for some menial and secretarial jobs. In June, Géry Pieret told Apollinaire that he had stolen a third statuette from the Louvre and kept it in his host’s lodgings. In August came the shocking news: the Mona Lisa had been stolen from the Louvre.

Géry Pieret smelling profit, or hoping for his 15 minutes of fame, presented himself as Baron Ignace d’Ormesan at the headquarters of the newspaper Paris-Journal. He bragged about how easy it was to steal from museums and as a proof of his audacity he handed over the recently stolen statuette.

While reading the article published by the newspaper, Apollinaire suddenly remembered the two other stolen statuettes bought by Picasso who kept them hidden in his sock drawer. In panic Picasso and Apollinaire ran out to throw the statuettes in the Seine but soon changed plans and decided Apollinaire would bring them to the offices of Paris-Journal. He tried to do this anonymously, but was arrested and put in jail. He was accused of involvement not only in the theft of the statuettes but also in that of the Mona Lisa.

Apollinaire informed the police that the thief of the three statuettes was Géry Pieret and that Picasso had bought two of them. By then Géry Pieret had left France, but Picasso was questioned by the police. Picasso was so scared he even denied knowing his friend Apollinaire. He was not jailed by lack of evidence. After six days in custody and after pressure from the Parisian art world Apollinaire was released and neither the painter nor the poet were charged with receiving stolen goods.

Apollinaire was devastated by the whole affair and the way he had been treated. Moreover, after leaving prison he was expelled from his apartment. Marie Laurencin and her mother had to shelter him in their house. A year later their turbulent liaison was over.

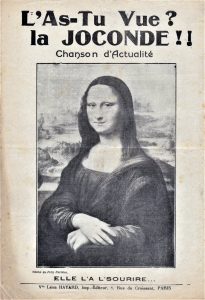

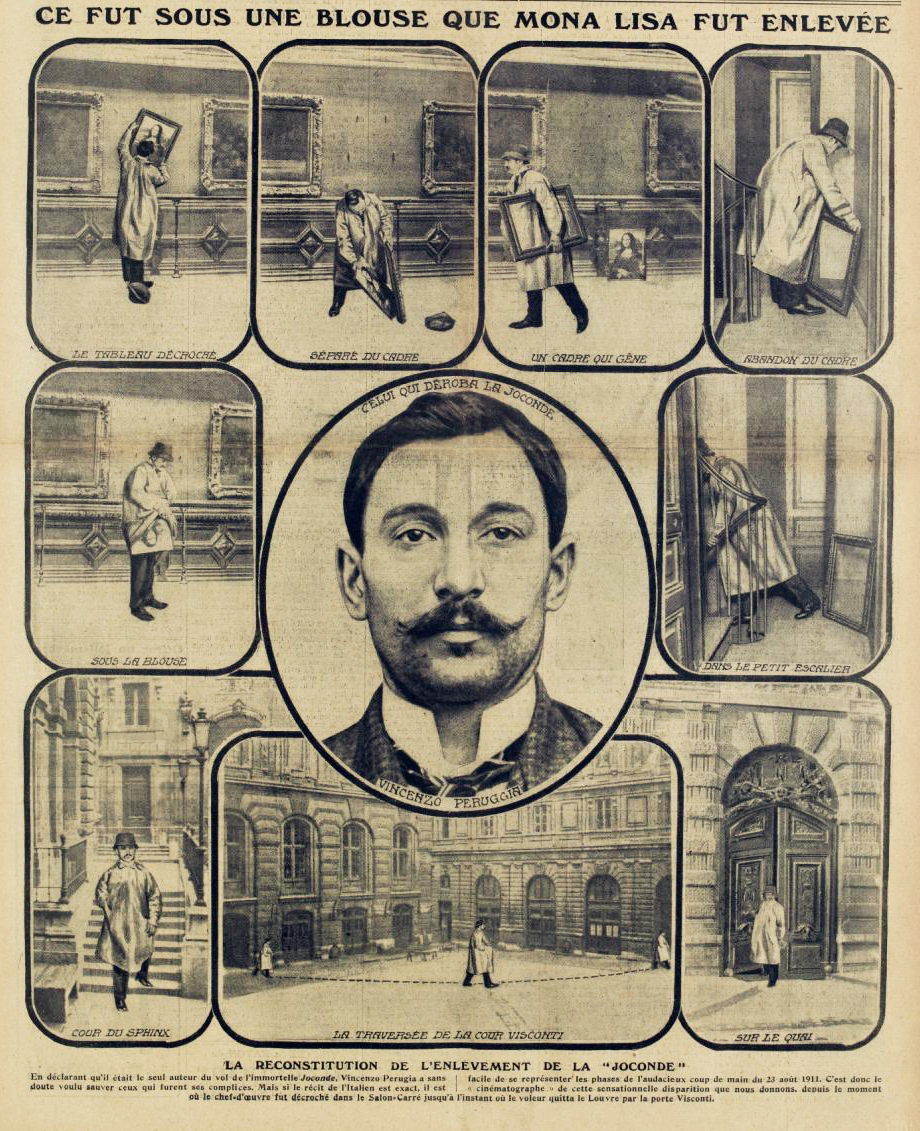

The real thief of the Mona Lisa, Vincenzo Peruggia, was caught in December 1913 when he tried to sell the painting in Firenze.

A newspaper illustration after his arrest illustrates that stealing from the Louvre was indeed not difficult at all. There were no alarms and the artworks were not firmly secured. The thief only had to unhook the painting, take it out of the frame, hide the canvas under his blouse and use a small staircase to leave the museum. Et voilà, as simple as that.

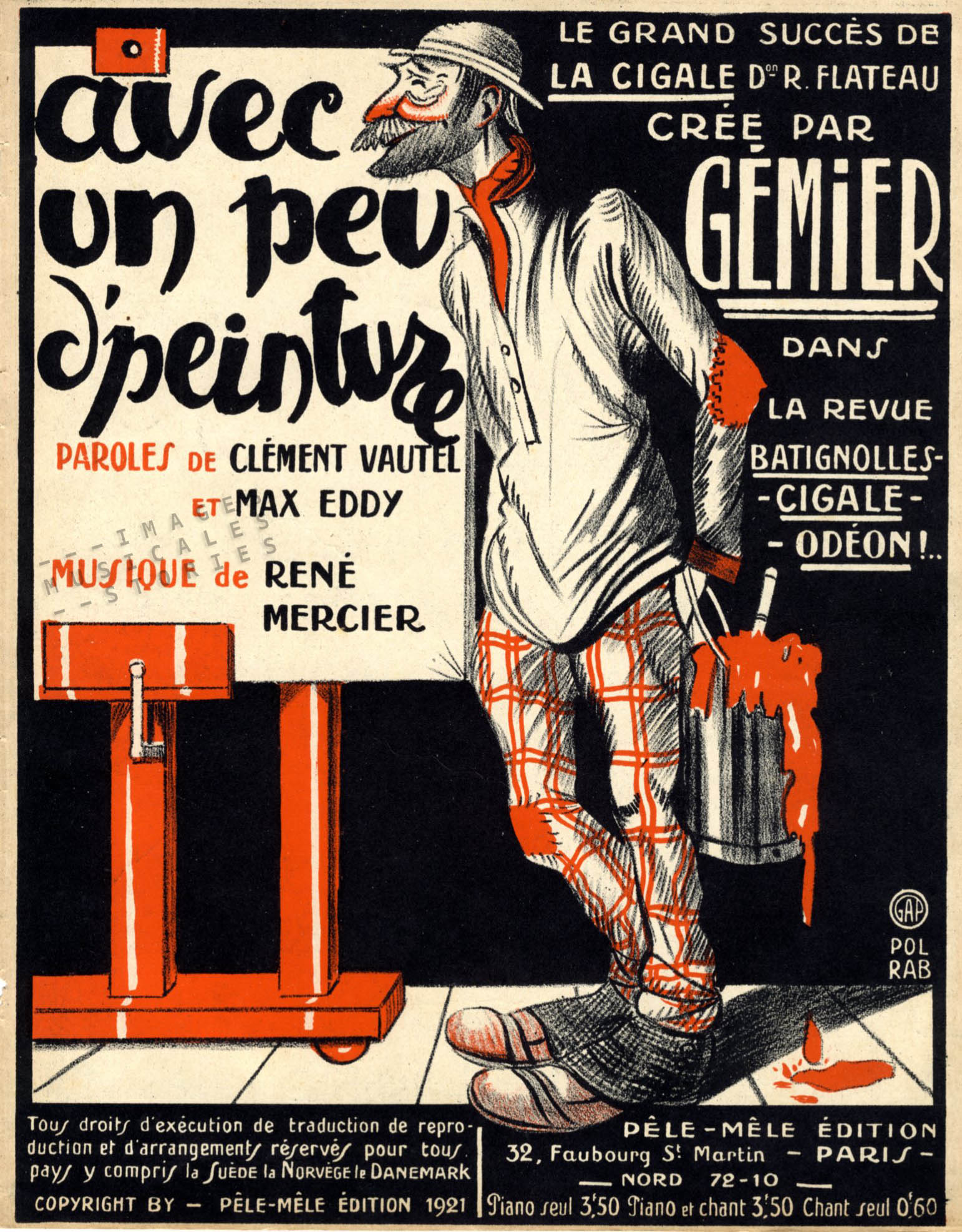

In 1931 the theft of the Mona Lisa was romanticised in a German film Der Raub der Mona Lisa. The same year Henri Sullivan composed his foxtrot Mona Lisa which has nothing to do with the film but the French sheet music has a wonderful cover illustrated by Kramer.

Our finale is also unconnected to the story of the great robbery. But Nat King Cole’s soft baritone voice will probably steal your heart if not your ear.