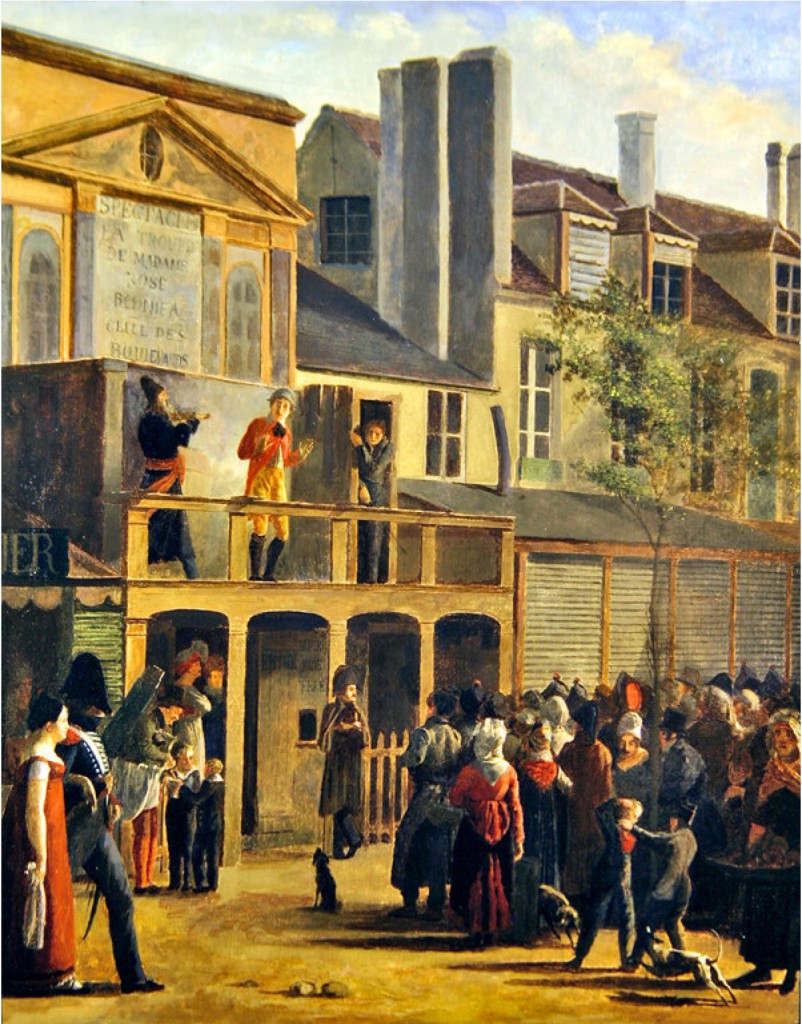

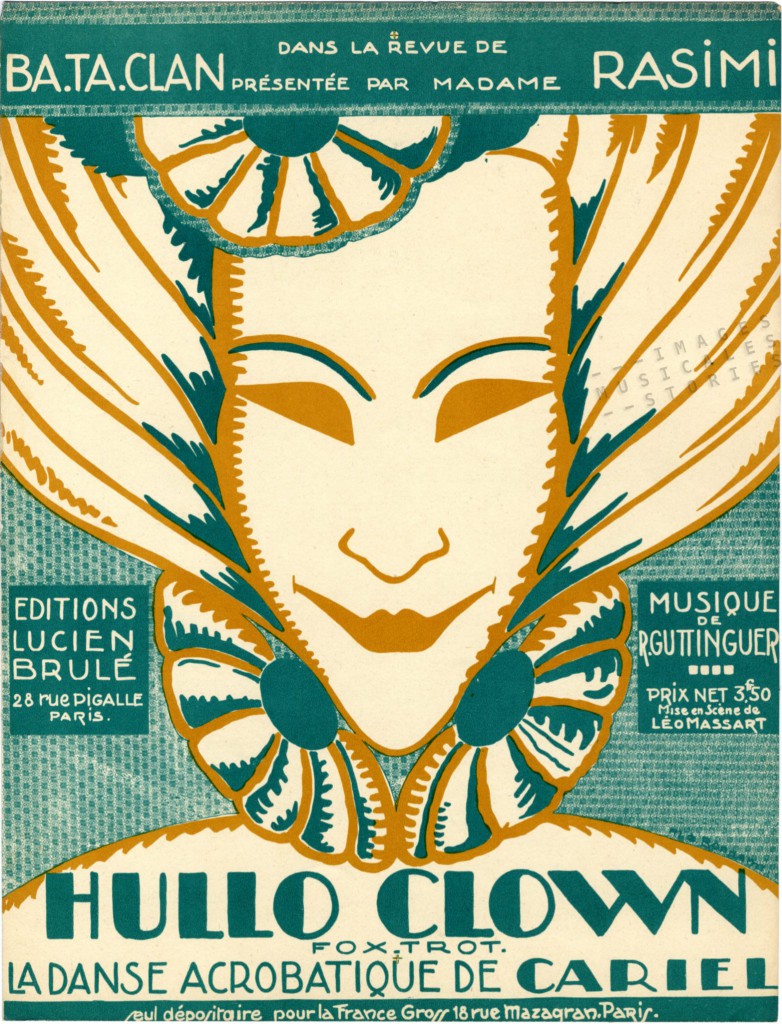

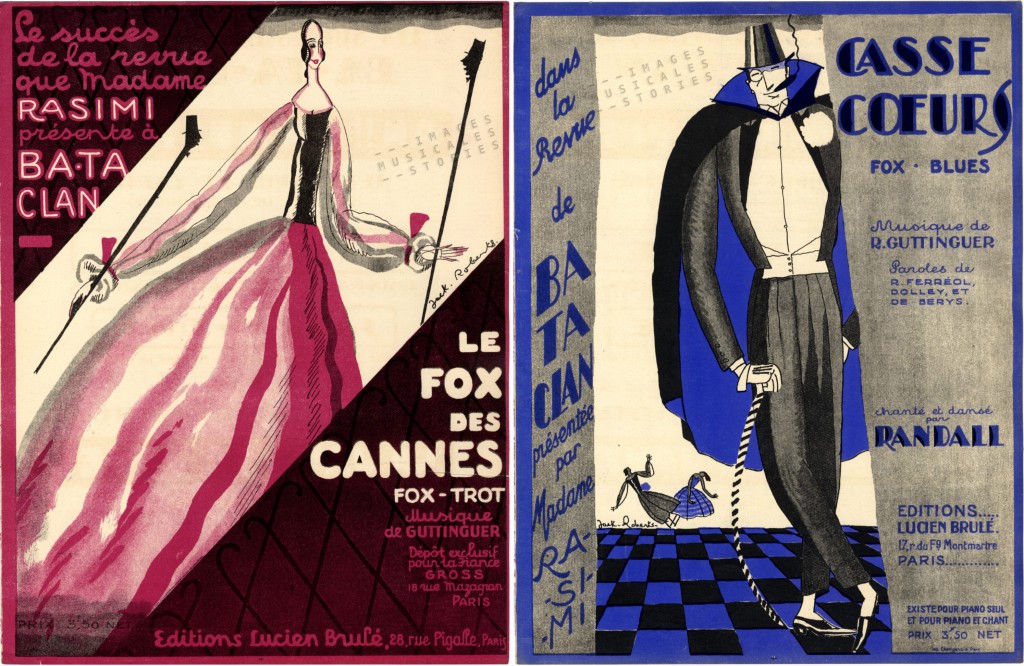

This captivating drawing of a clown by Marie-Antoinette Bonnami illustrates a song from one of Madame Rasimi’s revues. After her divorce from the director of the Casino-Kursaal in Lyon, she developed her own entertainment career in Paris. There she became the pioneer of revues with nearly-nude women, elegant costumes and lavish sets. Madame Bénédicte (aka Berthe) Rasimi was the owner of the Ba-Ta-Clan from 1910 until 1926. Under her direction the music hall achieved its greatest success.

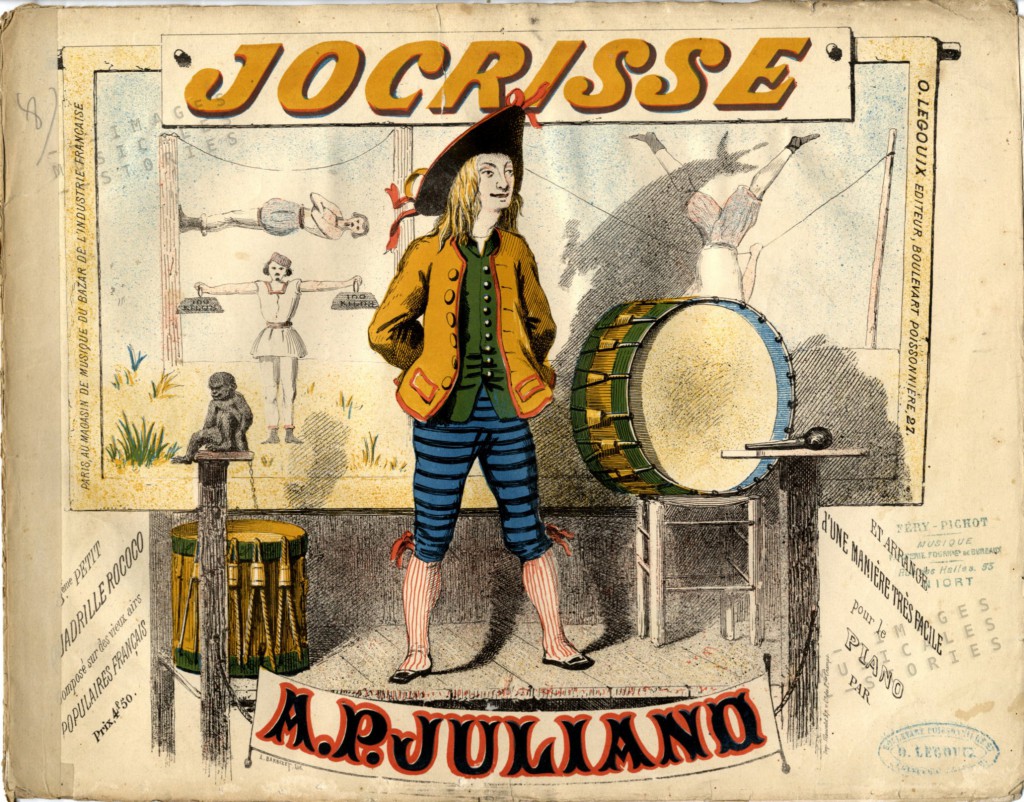

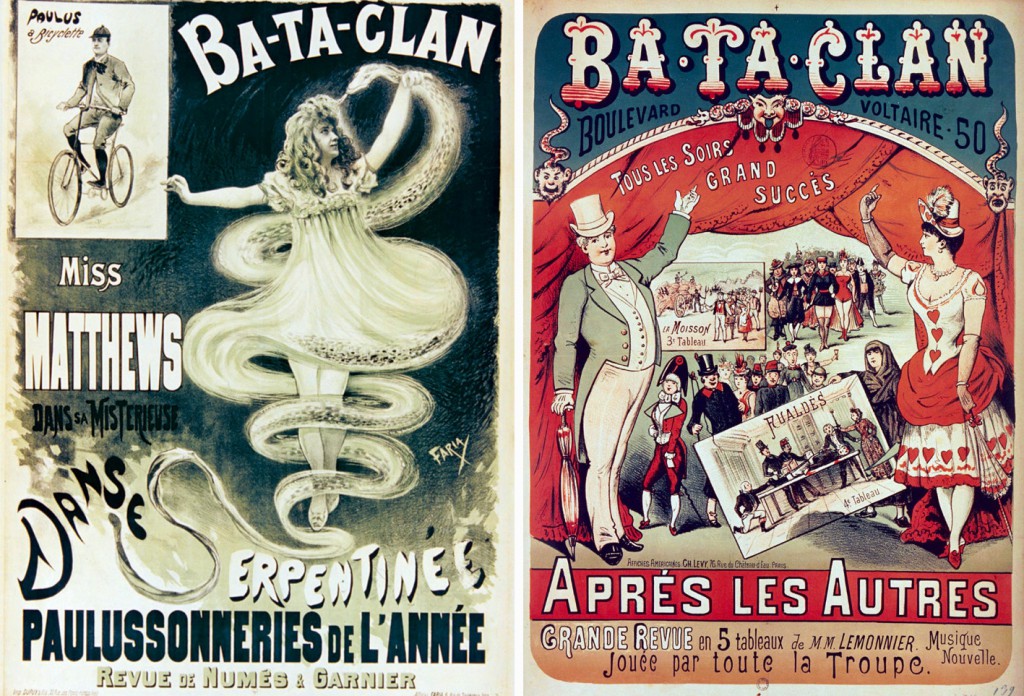

When it started in 1864, the Ba-Ta-Clan was a vaudeville theatre where people met to have a drink and watch jugglers and acrobats. Or one could see a ballet, listen to concerts, play billiards or have a dance. Its name was borrowed from Offenbach’s operetta, and its architecture and decor was equally inspired by the Chinoiserie musicale.

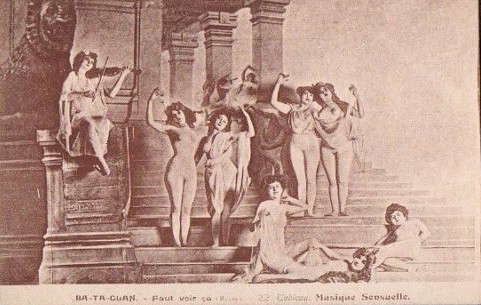

Madame Rasimi changed the Ba-Ta-Clan, but not into an elitist music hall nor in a theatre showing abundant nakedness (that reputation was reserved for the Folies-Bergère, l’Olympia and the Casino de Paris). In the Ba-Ta-Clan the audience rather revelled in the pleasure of discovering sumptuous decors and magnificent costumes, mostly designed by Madame Rasimi herself. And there were of course a host of big stars to overwhelm the public: Mistinguett, Maurice Chevalier, Parisys… Rasimi’s troupe brought acts which were a mix between chorus lines, classical ballet and tableaux vivants. But always intertwined with a bit of naughty nudity.

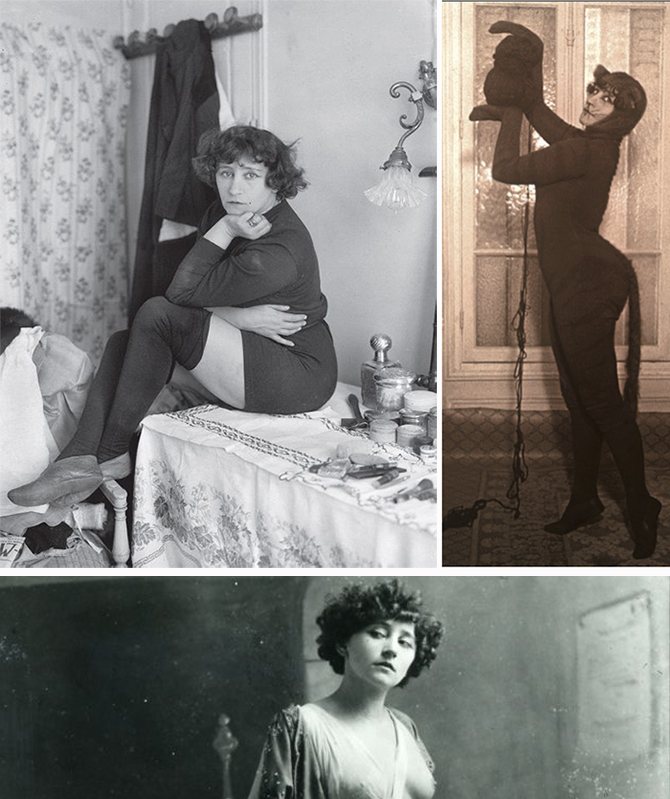

Thus, the writer Colette also performed for Madame Rasimi in 1911 and again in 1912. In the pictures below we see Colette in her dressing room in the Ba-Ta-Clan. Her costume for La Chatte Amoureuse is rather demure, but in other pantomimes she donned the obligate bit of nakedness.

In 1914 the Ba-Ta-Clan very optimistically announced its spring and summer revue: “The spring season will be the most amazing attraction in Paris during these splendid months…which only the hot July sun will be able to interrupt…The name itself ‘Y’a d’ jolies Femmes’ is a find. And be assured there will be a lot of beautiful girls, undressed with this exquisite art, suggestive, candidly lewd and deliciously perverse…”. And strangely, as a matter of fact the outbreak of the First World War was by no means counterproductive for the Ba-Ta-Clan. Au contraire, Madame Rasimi put on no less than 18 revues!

During the Great War the theatre programs all had the same illustration by Georges Lepape: a girl in a garden who has to choose between a mysterious missive from a masked man or a rose from a toothless devil.

Also during the war, in 1917, Madame Rasimi staged the famous oriental pantomime L’Orient Merveilleux ou 1002 Nuits de Bagdad with two of the biggest stars of the music hall, Maurice Chevalier and Mistinguett. The famous Erté designed and costumed an entire act which featured the favourite of the caliph wearing ropes of pearls around her breasts and harem pants.

After the war, in the roar of the Twenties, Lucien Brulé published gorgeous covers for Madame Rasimi’s productions. They were illustrated by Jack Roberts and by Marie-Antoinette Bonnami.

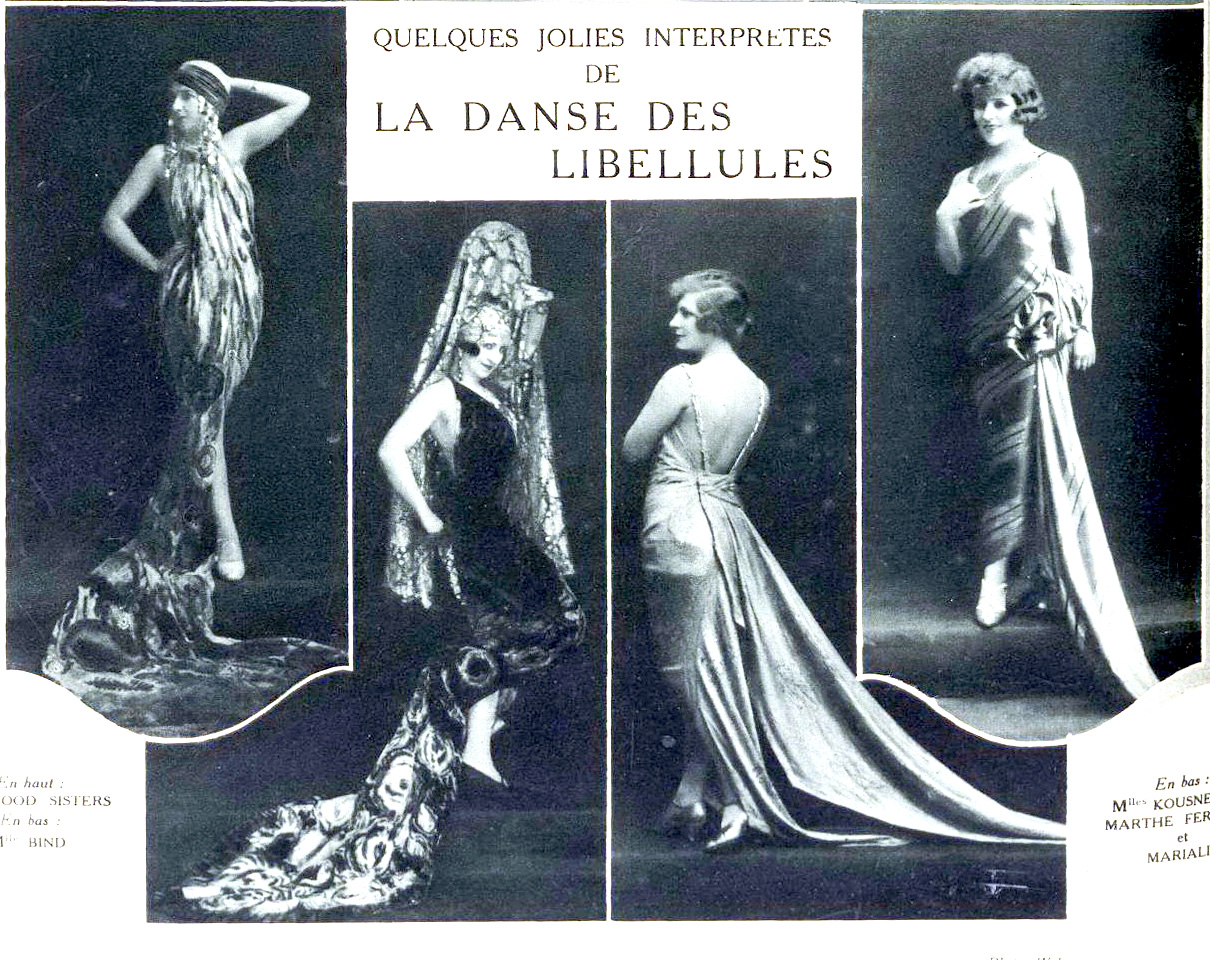

In contrast to the shows, the covers of the sheet music are rather demure and prudish, probably not to shock the publisher’s larger public. The only titillating cover we have found so far for Madame Rasimi’s productions, is for the Danse des Libellules by Franz Léhar. The illustration is by Georges Dola, though he also made a more mainstream cover for this same popular Ba-Ta-Clan revue.

The pictures below show a few examples of Madame Rasimi’s costumes for La Danse des Libellules.

In 1921 Madame Rasimi produced an abridged music-hall adaptation of the surrealist ballet Le Boeuf sur le toit by Darius Milhaud. She included that personalised version of Le Boeuf sur le toit in one of her revues, of course with a lot of nudity and humour.

In 1922 Madame Rasimi took her ensemble on a first South American tour. Other tours would soon follow and her shows were a great sensation in Buenos Aires, Montevideo, Rio de Janeiro and Mexico City. During her first visit she had a conflict with the Brazilian press, who accused her of caricaturing the Brazilian people in her version of Le Boeuf sur le Toit. Madame Rasimi hastened to state in a letter that Ba-Ta-Clan had never offended or ridiculed Brazil in any of its revues: the ultramodern pantomime Le Boeuf sur le Toit, although inspired by Brazilian music only parodied the American Prohibition law. She must have mollified the Brazilian press as her revue became an instant success.

Madame Rasimi’s spectacles triggered a new South American concept, bataclanismo and the bataclana. At the time the word bataclana was used to indicate a kind of female star who represented the erotic, and more dangerous aspect of the flapper. Later the term was used to indicate an actress who is supposedly singing or dancing but is really just showing off her body, and by extension a stripper.

Unfortunately, a tour of South America and the Caribbean in 1926 ruined Madame Rasimi and she had to sell the Ba-Ta-Clan. She bid farewell to her beloved chorus girls who nicknamed her Madame Rase-Mimi (Mrs. Shave-Mimi) because she told them to shave their eyebrows and armpits. Still, Madame Rasimi continued her career as a costume designer well into the Fifties.

Madame Rasimi’s Ba-Ta-Clan was a place for lightness and joie de vivre, not a place for horror. For the moment, I’ll just pretend there is no evil in the world and play an innocent game of Ba-Ta-Clan.

Further reading: Bataclanismo ! Or, How Female Deco Bodies Transformed Postrevolutionary Mexico City by Ageeth Sluis