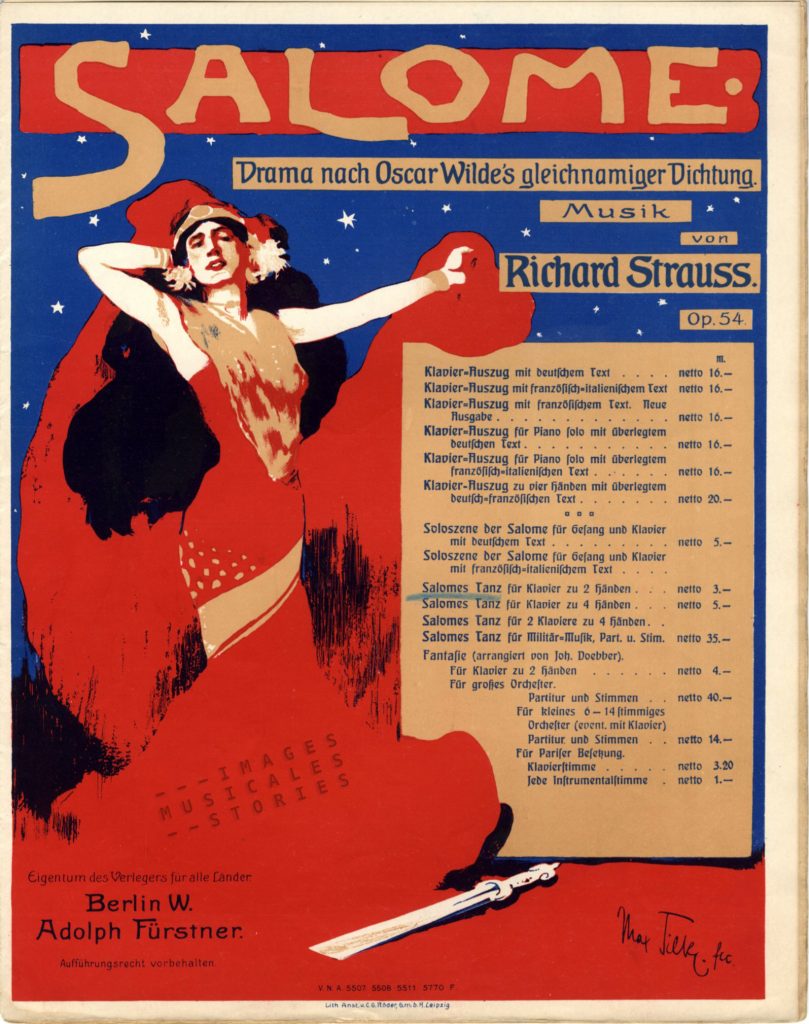

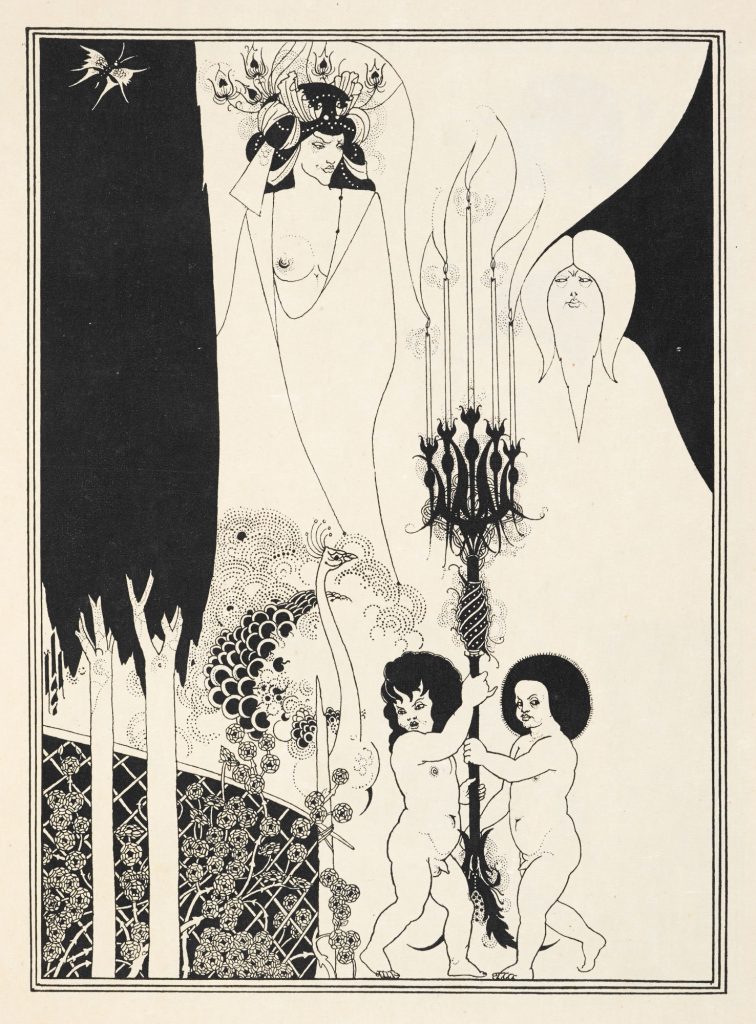

This German cover lusciously portrays the infamous Salome, femme fatale par excellence. Salome is the title of an opera by Richard Strauss, based on Oscar Wilde’s play. Wilde wrote the play in French in 1891, and it was thus published in France two years later. An English translation was published in 1894, with iconic illustrations by Aubrey Beardsley.

The London premiere of Salomé, with Sarah Bernhardt as the lead, was banned on the pretext that it was legally not allowed to put biblical stories on stage. As a result Salomé was first performed in Paris in 1896. Oscar Wilde was then in London serving his two-year prison sentence for gross indecency.

For his play Wilde elaborated on a bible story: Salome is the teenage stepdaughter of king Herod. All the men at the court —including Herod himself— are overwhelmed by lust for her. However Salome only has eyes for Jochanaan (John the Baptist) who is kept captive in Herod’s prison. John the Baptist, a denouncer of sin who has committed his life to God, obviously rejects her and starts to preach about the Son of God. Salome is so furious about his prudery that she plots to get him killed. It is with an erotic dance (the Dance of the Seven Veils) that the deranged teen plans to make her stepfather promise to fulfil her most outrageous desire.

Whatsoever thou shalt desire I will give it thee,

even to the half of my kingdom,

if thou wilt but dance for me.

O Salome, Salome, dance for me!

Indeed, after Salome’s dance Herod is in ecstasy and makes his foolish promise. Salome asks for only one thing:

I would that they presently bring me in a silver charger . . .

the head of Jochanaan.”

Such a salacious play, with its shocking representation of female lust, of course caused an enormous scandal all over Europe. And it caught the attention of Richard Strauss. He wrote the libretto himself based on a German translation of Wilde’s play. Strauss completed his opera in 1905. Both the operas of Berlin and Vienna refused to show Strauss’s scandalous work so he had to premiere it in the more progressive Dresden.

The first interpreter of Salome at Dresden, the matronly Frau Wittich, a singer with Wagnerian power, refused to perform the Dance of the Seven Veils. As Strauss understood that a ten-minute striptease would boost the ticket sales, he hired a body double for the scene. Kaiser Wilhelm remarked at the time: “I really like this fellow Strauss, but Salome will do him a lot of damage.” In his Recollections and Reflections published in the year of his death, Strauss dryly retorted: “The damage enabled me to build me my villa.” The Finnish Aino Ackté was the first Salome singer to dance the Dance of the Seven Veils herself. That was in 1907.

Listen to Strauss’ hauntingly beautiful Ich habe deinen Mund geküsst. In this necrophiliac scene the obsessed teenage girl Salome passionately makes love to the death body of John the Baptist and kisses his cold lips: “You wouldn’t give your lips to me, well I will kiss them now.”

Ah! Ich habe deinen Mund geküsst, Jochanaan.

Ah! Ich habe ihn geküsst, deinen Mund.

Es war ein bitterer Geschmack auf deinen Lippen.

Hat es nach Blut geschmeckt?

Nein! Doch es schmeckte vielleicht nach Liebe. . .

Sie sagen, dass die Liebe bitter schmecke. . .

Oscar Wilde’s play and Strauss’ opera and Wilde’s play fuelled a Salome craze. The rage spread throughout Europe and America at the beginning of the 20th century.

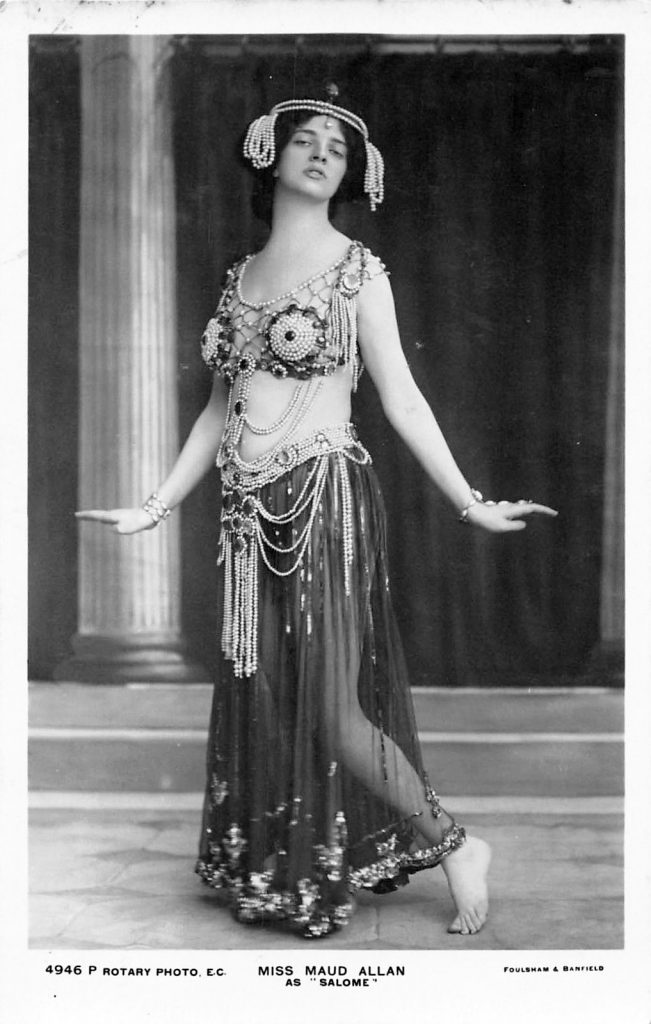

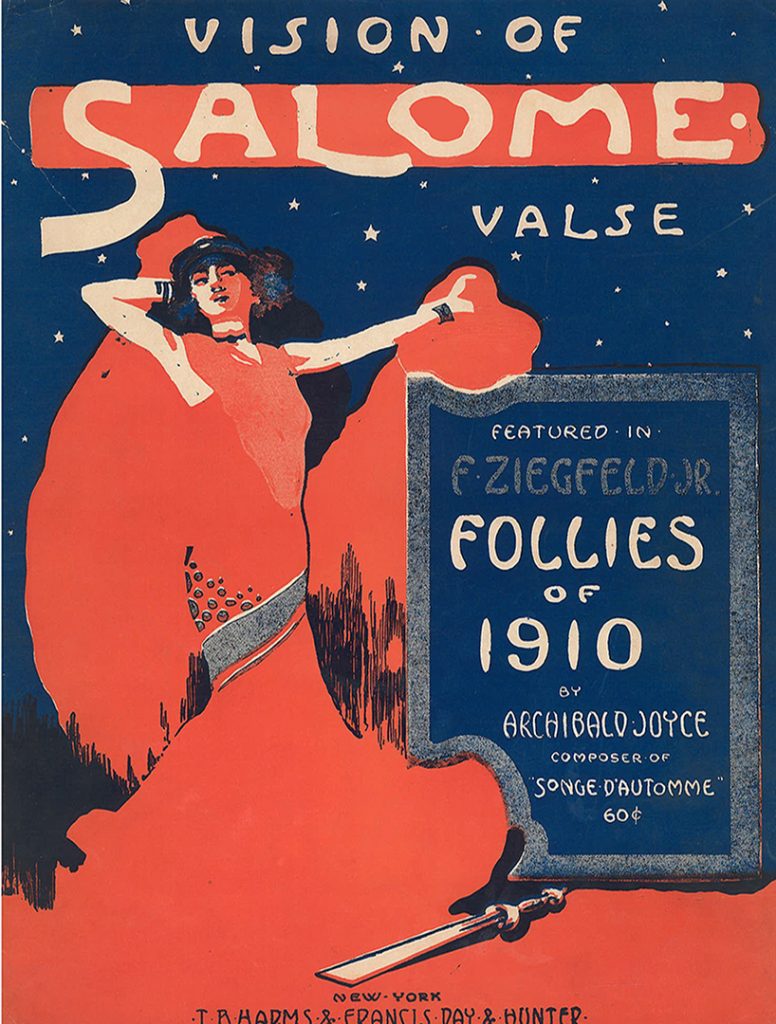

These two sheet music of Vision of Salomé by Archibald Joyce, both show us Maud Allen, a dancer who stunned (or unsettled) the audiences with her erotic dancing. She became a controversial sensation with the performance of her own production Vision of Salome in London in 1908 (loosely based on Wilde’ original play). She is drawn here in her typical risqué costume consisting of a beaded bustier and jewel-encrusted transparent skirt.

But the pictures of Maud Allan on these covers are misleading. Archibald Joyce, known as the English Waltz King, wrote for a bourgeois clientele: popular dance orchestras and amateur pianists. His Vision of Salome was a popular simple waltz published in 1909, triggered by Maud Allen’s success but absolutely not composed for her titillating performance, which was already launched in Vienna three years earlier.

The American publisher of Archibald Joyce’s Salome almost copy-pasted the original drawing by Max Tilke for Richard Strauss’ opera, perhaps to give the popular waltz a more highbrow character.

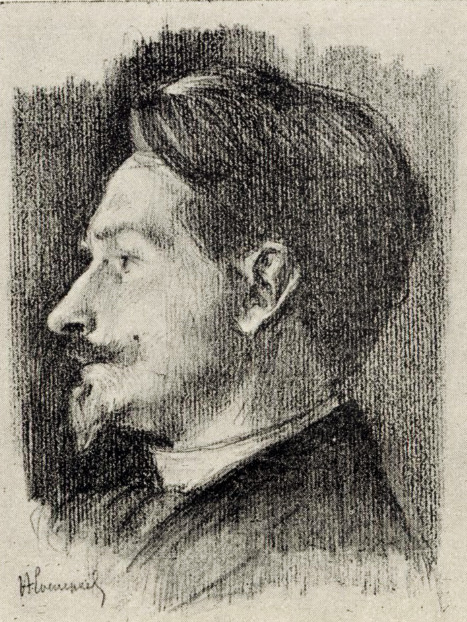

The (real) music for Maud Allan’s performance was composed by the Belgian bohemian and anarchist Marcel Rémy, a journalist, composer and amateur of the ancient arts. Rémy was introduced to Maud Allan in Berlin and quickly became her agent-manager. During some years they created dances based on poses found on ancient Greek amphorae. He played the piano while she practised her dancing. Just before he died of syphilis, Rémy wrote Vision of Salome for Maud, the work that would make her world-famous. He did not live long enough to attend its premiere nor to participate in its success.

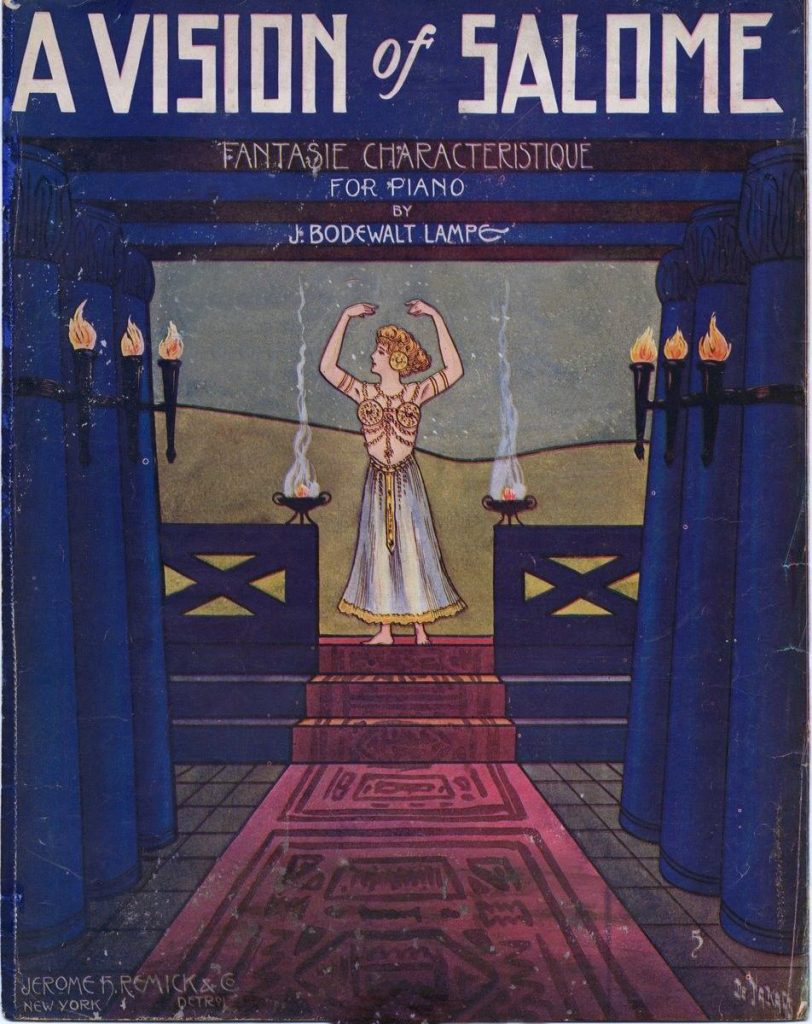

Another Vision of Salome, this time a Fantasie Characteristique by Bodewalt Lampe, found its way in our story. The indefinite article ‘A’ in the title A Vision of Salome confirmed our suspicion that the dancer on the cover is not Allan Maud. Instead it is a somewhat naive rendition of the copy-cat dance by Gertrude Hoffmann.

Gertrude was an American chorus girl who went to London to study Maud Allan and came back to offend the public decency with her version of the Salome dance (she threw in a bit of cancan) in an identical outfit.

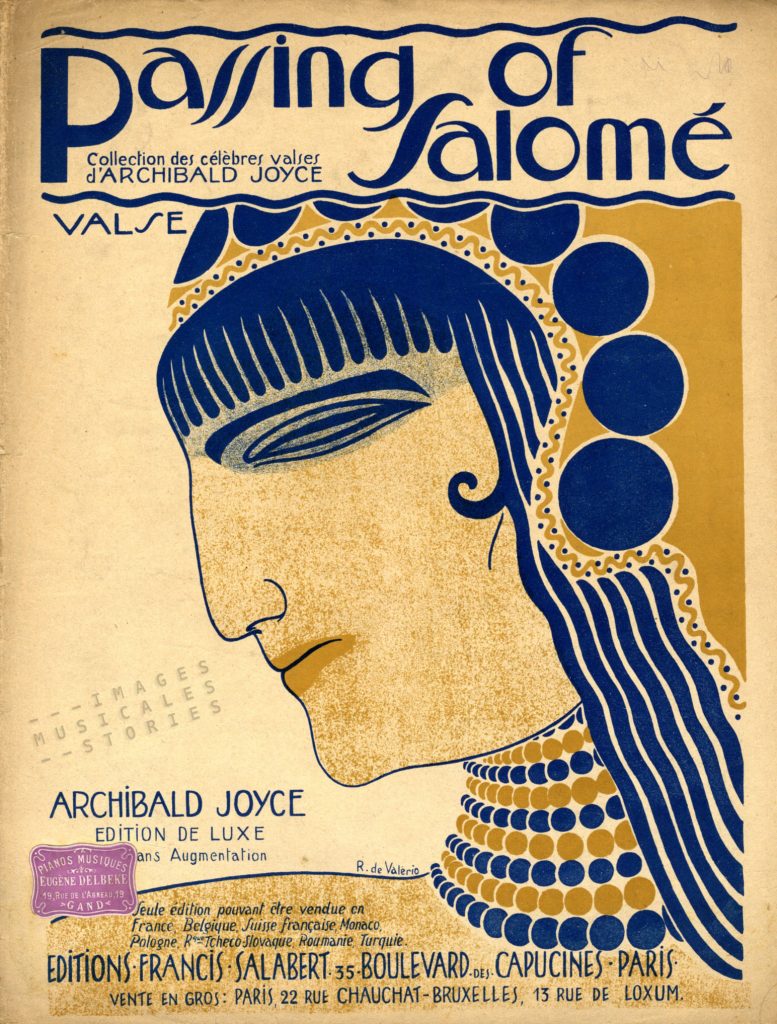

In 1912 Archibald Joyce was financially inspired to compose a sequel: The Passing of Salome. Although Maud Allan was still hot at that time, Roger de Valerio did not need her lascivious pose to draw this striking cover for the Salabert publication.

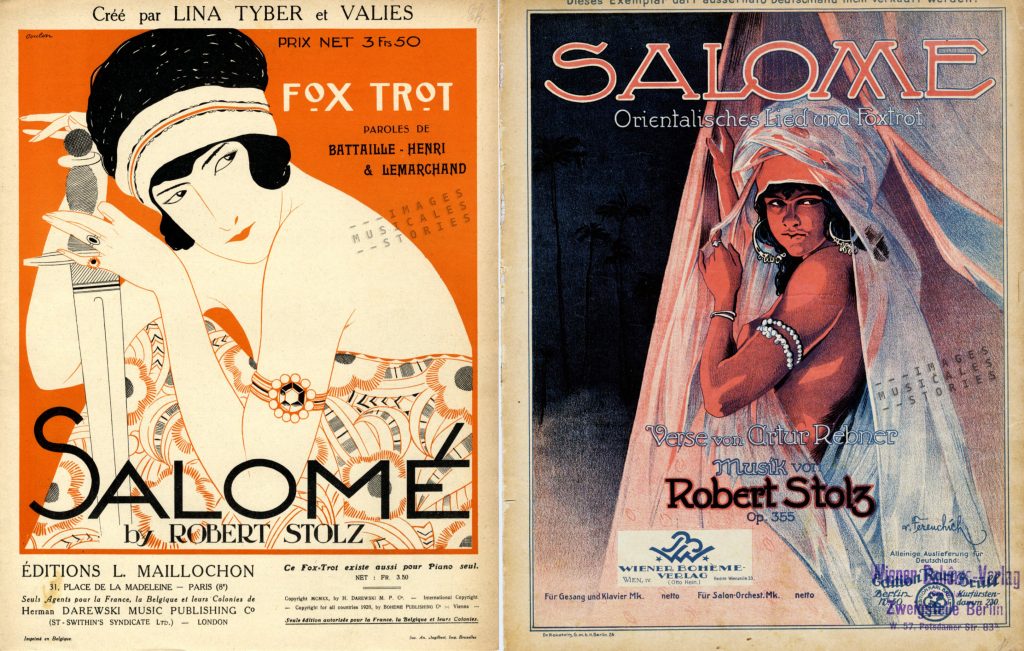

It would be the last song from the Salomania which had started in 1908. The rage would revive for a short while when Robert Stolz, the celebrated and prolific Austrian composer, created Salome, together with lyricist Arthur Rebner in 1922.

The Stolz fox-trot was published in the States as Sal-O-May to promote the German pronunciation. I’m sure everyone will know this song.

A song that Petula Clark took into the charts in 1961 as Romeo.

And now the frivolous sexy dance! In a silent film version from the 1920s, Alla Nazimova performs the Dance of the Seven Veils. The film uses minimalist sets and elaborate stylised costumes. It might look a little bit tame by today’s standards but at that time it must have been raunchy and shocking.