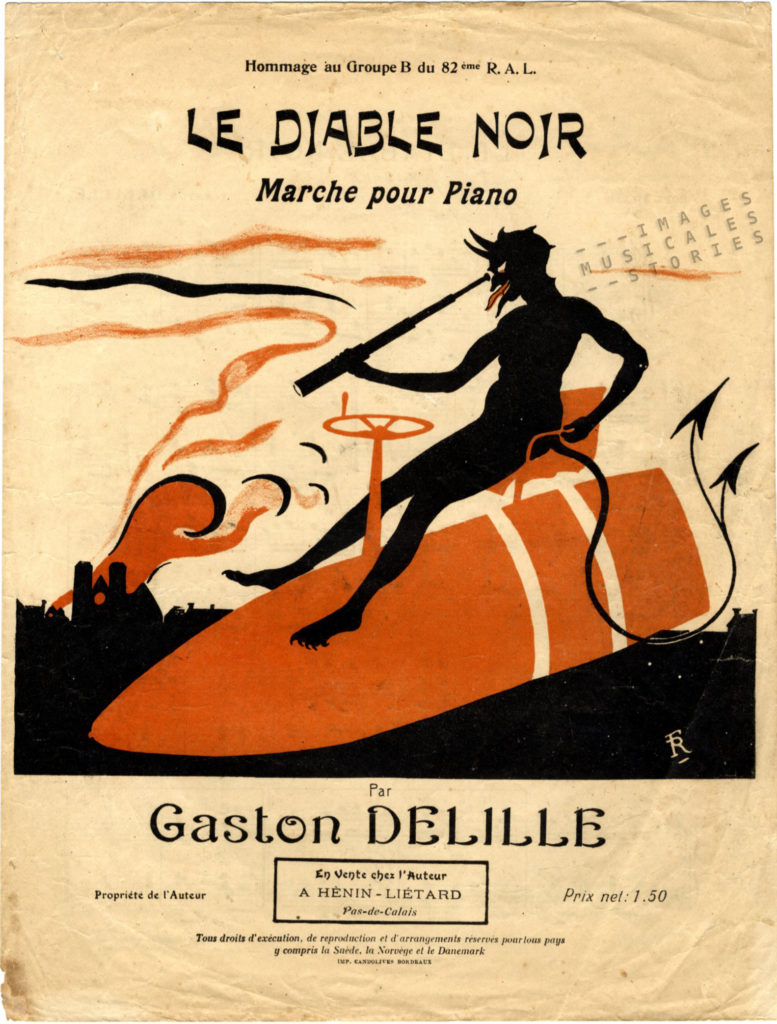

The march ‘Le Diable Noir’ is a tribute to a French heavy artillery regiment during WW1. German soldiers allegedly nicknamed French gunners ‘Diables Noirs’, or Black Devils, referring to the colour of their uniform and also to the gunpowder that blackened their faces.

Thanks to Gaston Delille’s great-grandchild (active on Reddit as balfringRetro) we can listen to a recording of Le Diable Noir.

On this week’s sheet music cover we see a black devil sitting atop a red bomb, leering through his binoculars at a ruined city. The projectile has a childish steering wheel. The two telltale circular marks on the grenade let us guess it is a naive drawing of a French 400 mm artillery shell. These bomb types were fired from a railway gun, a large artillery piece or Howitzer, mounted on a specially designed railway wagon. They were the French answer to the German Big Bertha.

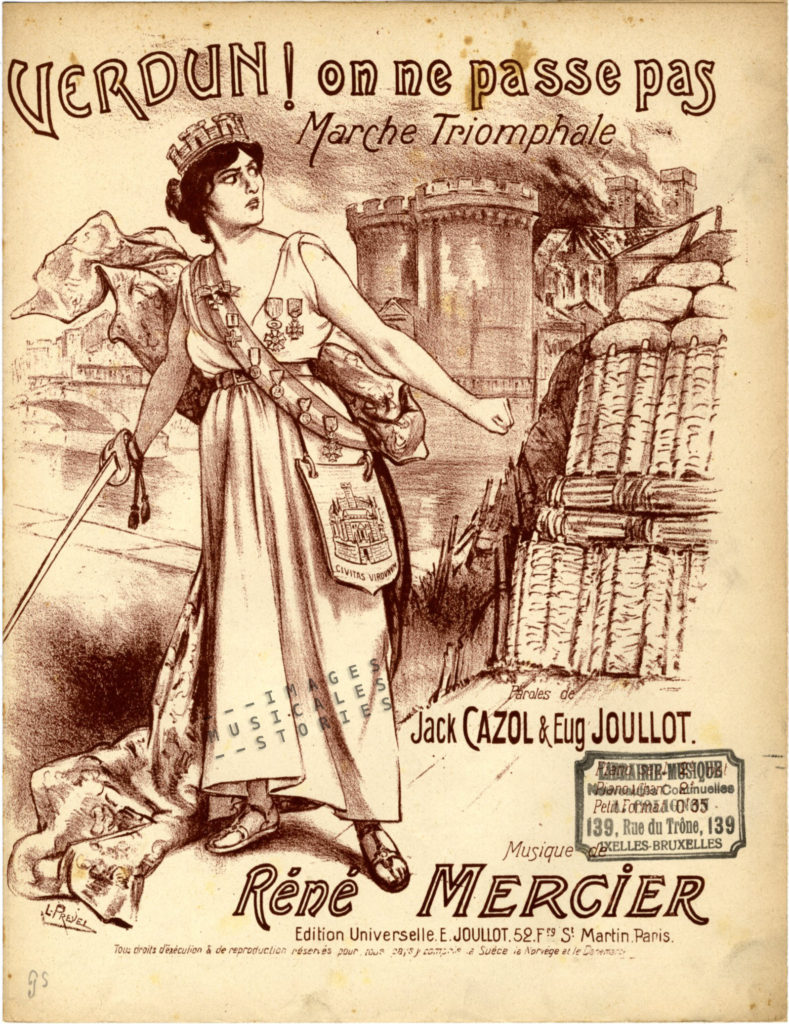

The 400 mm railway gun was first put into service during the battle at Verdun. The thing was so heavy and clumsy that it took two days to set it up.

The 400 mm railway gun was first put into service during the battle at Verdun. The thing was so heavy and clumsy that it took two days to set it up.

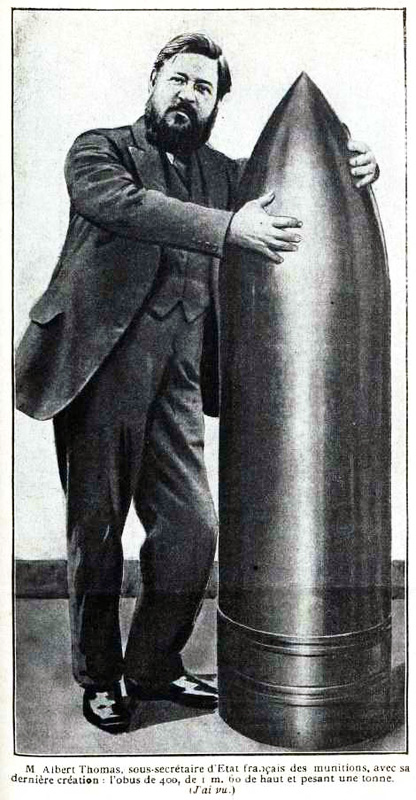

The person responsible for manufacturing the ‘Obus 400‘ bomb was Albert Thomas. He was the French minister of Armaments during WW1. A socialist and pacifist, he had cooperated with Jaurès, the leader of the French Socialist Party who was murdered in 1914. In this photo collage we see him proudly and lovingly presenting his 1.000 kg bomb.

When the war broke out in August 1914, the French socialists had swallowed their anti-war resolutions to patriotically join the defence of their country. The left wing agreed to a political truce, the Union Sacrée, promising not to oppose the government during the war. Albert Thomas was the epitome of this Sacred Union: the pacifist had become a top manufacturer of weapons by modernising France’s munitions production. He retrieved half a million men already serving with the army, also recruited prisoners of war, refugees and women and put all these people to work to massively make ammunition. At the same time he tried to improve the working conditions in the arms industry, although with little immediate success. In 1917 the French Socialist Party left the Union Sacrée, and Albert Thomas resigned as minister of Armaments. His fight to optimise the war efforts had made him an outsider in his own party, where pacifism was again de rigueur.

What better way to finish this post than with the catching tune of ‘Ancient Combattant’, an ironic anti-war song by the Congolese Casimir Zoba: La bombe ce n’est pas bon, ce n’est pas bon: le diable noir cadavéré!

Marquer le pas, et 1, 2

Ancien combattant

Mundasukiri

Tu ne sais pas que moi je suis ancien combattant

Moi je suis ancien combattant,

J’ai fait la guerre mondiaux

Dans la guerre mondiaux,

Il n’y a pas de camarade oui

Dans la guerre mondiaux,

Il n’y a pas de pitié mon ami

J’ai tué Français,

J’ai tué Allemand

J’ai tué Anglais,

Moi j’ai tué Tché-co-slo-vaque

Marquer le pas, 1, 2

Ancien combattant

Mundasukiri

La guerre mondiaux

Ce n’est pas beau, ce n’est pas beau