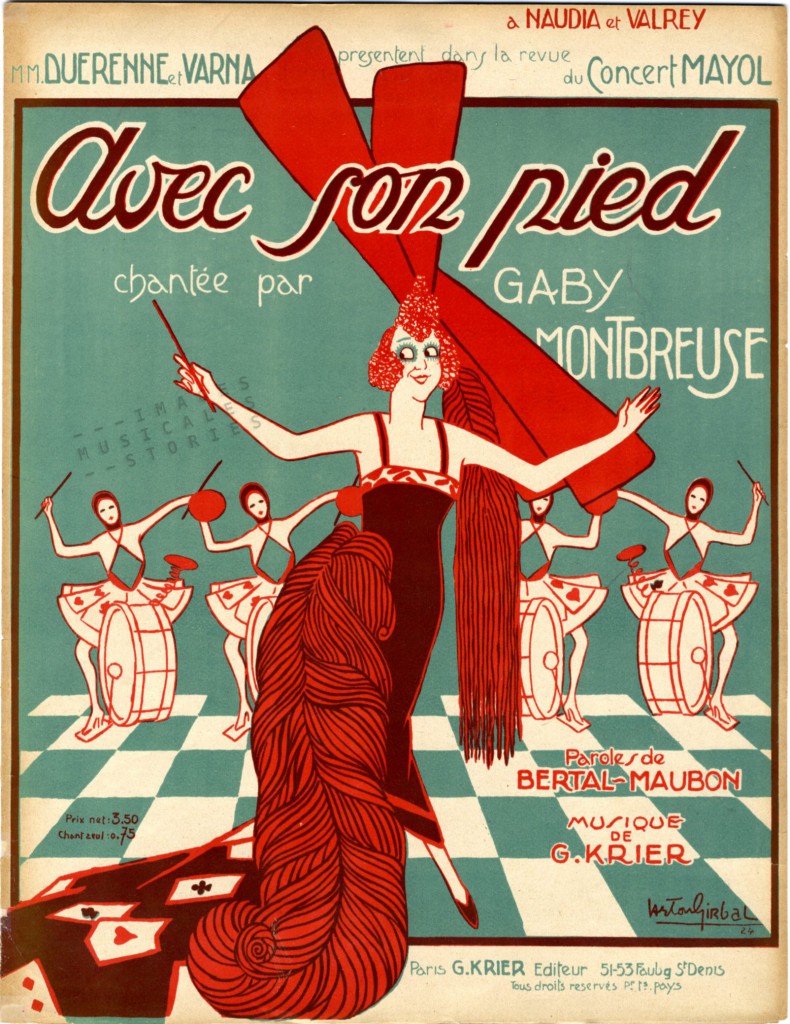

For this cover Gaston Girbal drew a caricature of Gaby Montbreuse with a characteristic oversized bow in her hair.

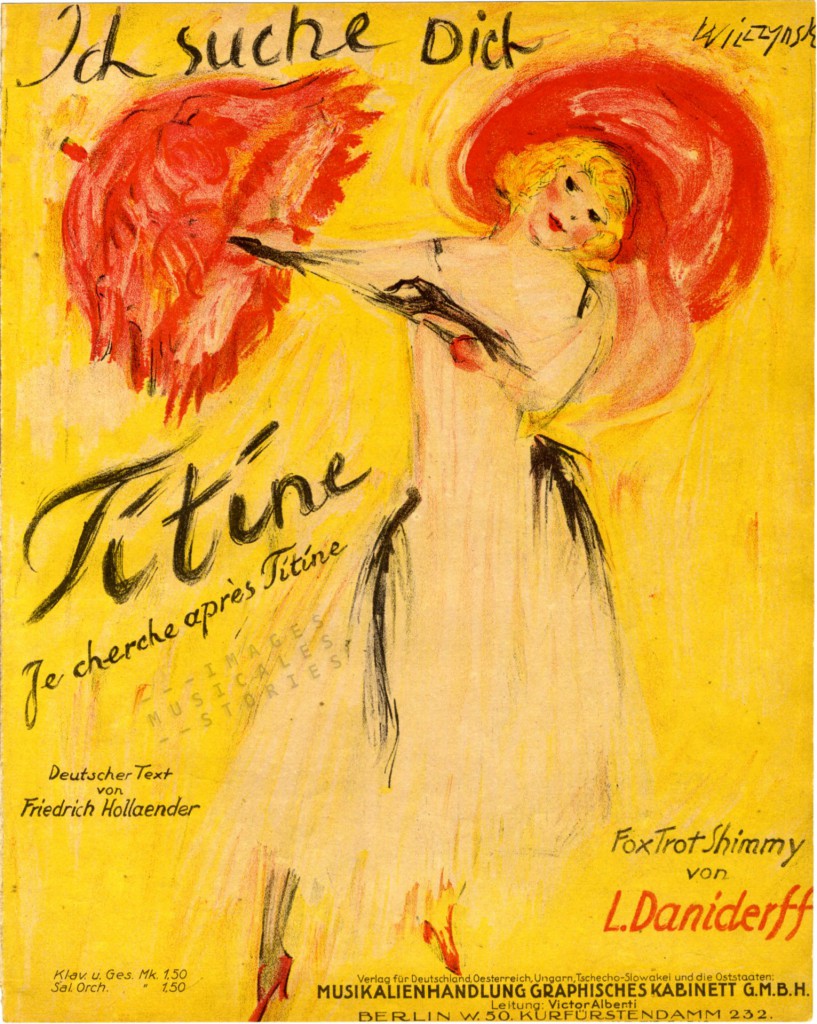

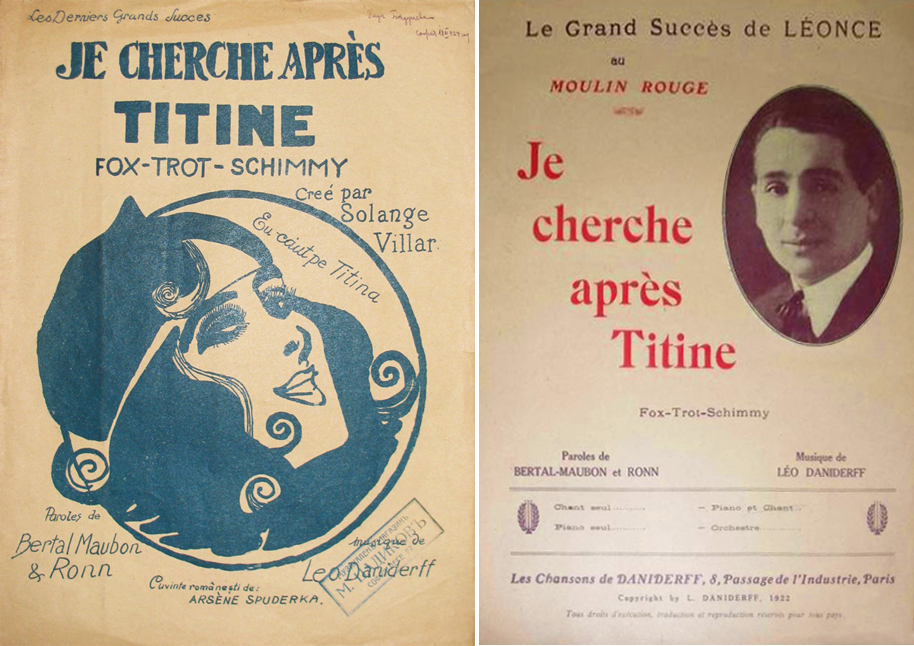

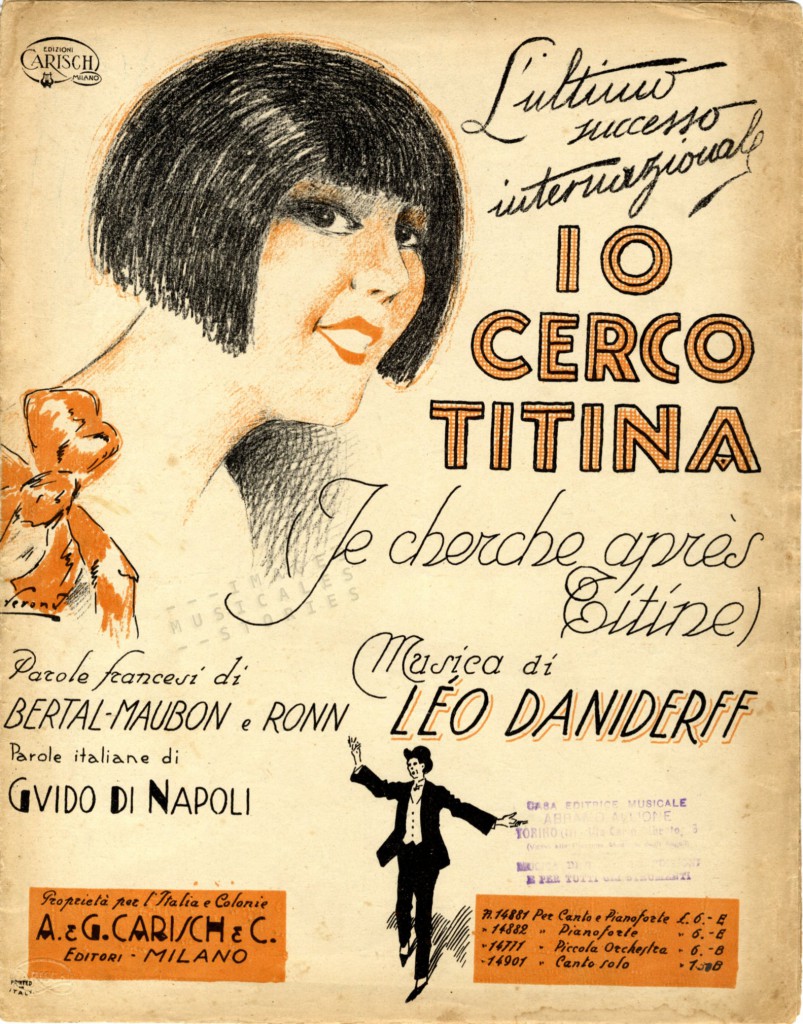

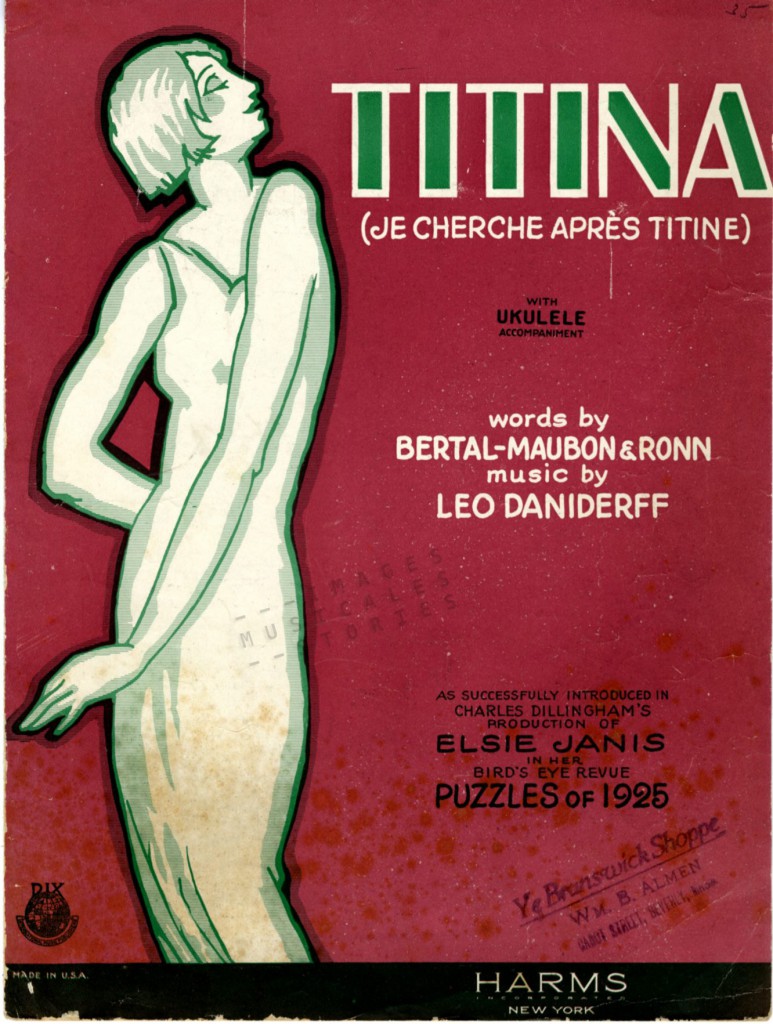

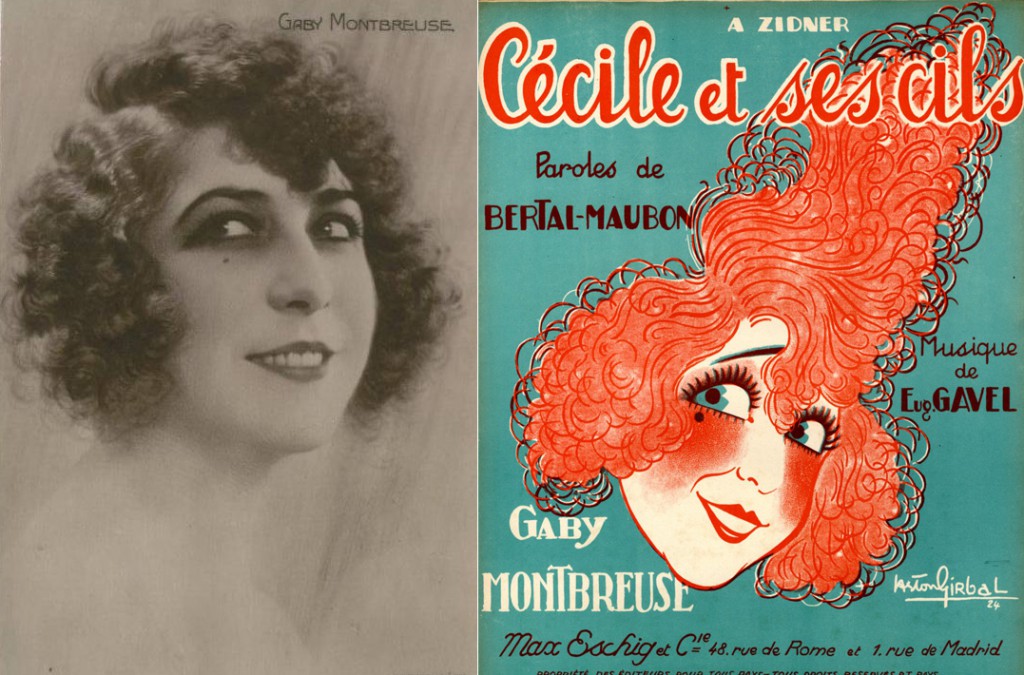

Little is known about her rather short life. In 1913 Gaby Montbreuse (Julia Hérissé) made her debut at 18 with the song Sur la Riviera, composed by Léo Daniderff. It is said that Daniderff was her companion for some years and wrote many of her songs, the best known Je cherche après Titine.

It is odd that at least two of her well-known songs of her early career were also sung by a ‘Gaby Zetty’ (or Zety?) about whom even less is known… An alter ego, a competitor or an abandoned nom d’artiste? Bizarre…

Gaby Montbreuse’s picture on the cover of Sur la Riviera still looks quite conventional but she would become increasingly extravagant.

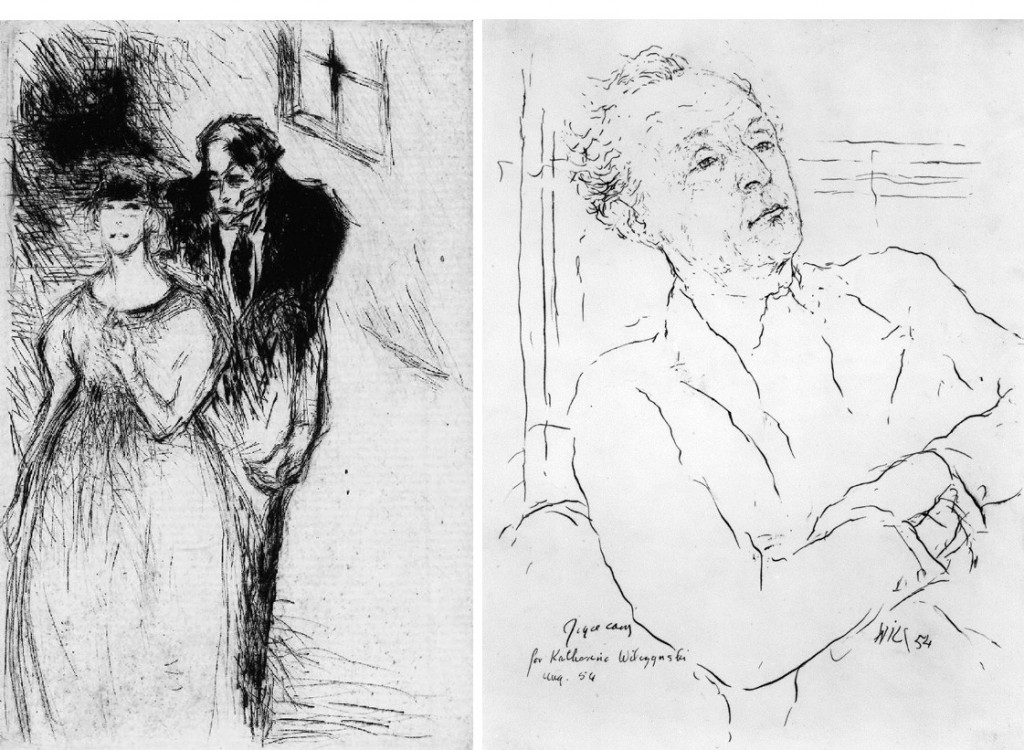

The composer Georges Van Parys who accompanied her on the piano in 1924 described her in his journal without mincing his words:

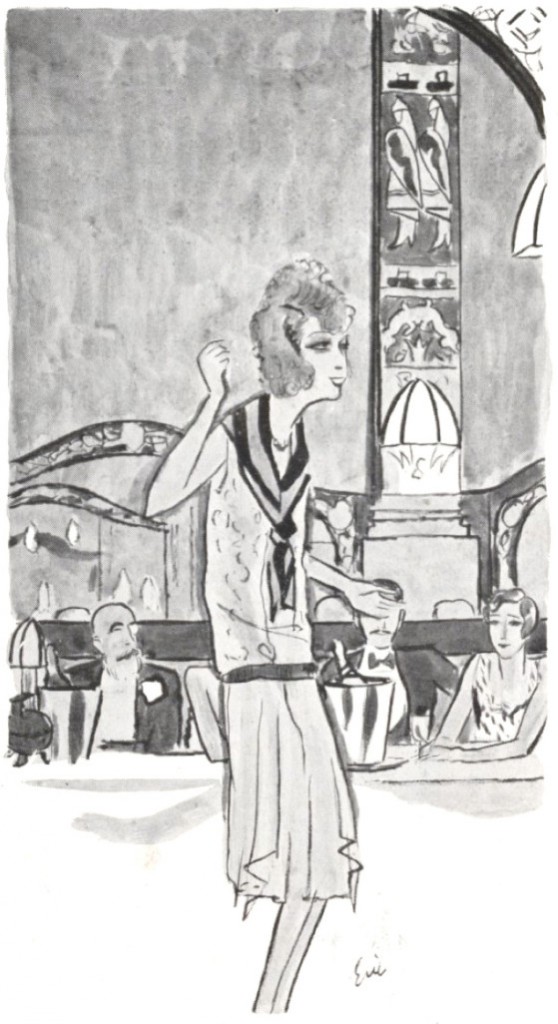

“She surely is ugly and looks awful. A huge round head, absolutely disproportionate to her body. A shock of curly red hair, with a lock tumbling on her forehead. Very useful, this lock: she gets a comic effect by blowing on it when she feels in the middle of a song that it does not work well. Made up like a baby doll, with eyelashes painted like a fan upon her eyelids. Her voice is working-class, vulgar, cracked by abuse. Vulgar gestures are carefully studied. All this would, without doubt, be unacceptable from someone else. But the good woman is so funny that even the most critical are quickly disarmed. Uplifting her skirt with her left hand, she begins to sing eye-watering silly verses. Yet she manages to make people laugh who, until proven otherwise, seem perfectly normal.”

Pol Rab also caricatured Montbreuse’s physique on sheet music covers from the Parisian Années Folles.

After performing in all the well-known Parisian cabarets and a short film career, she opened her own night club ‘Le Château Montbreuse’ in the late Twenties. Alas, her venue went bust in the early Thirties, and she again appeared in the entertainment programs of other concert halls and clubs. Not much is known about the rest of her life, but she reportedly died in Tours in 1943.

If you are curious about her voice, here she sings the bawdy Tu m’as possédée par surprise.

Tu m’as possédée par surprise (for the french lyrics, click here)And if Gaby Montbreuse were a man and a hippie, maybe she would have looked like Armand. He was a protest singer, nicknamed the Dutch Bob Dylan (for lack of better). I adored him in the late Sixties when I still thought all was love, peace and happiness. Even in his sixties he dignified to keep his Sixties look. But his iconic song from 1967 hasn’t changed a lot. Groovy, outta sight man!