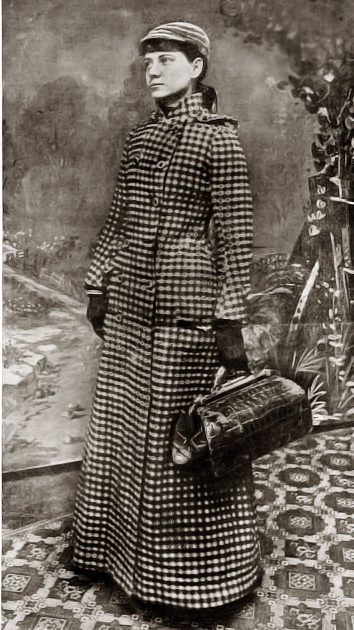

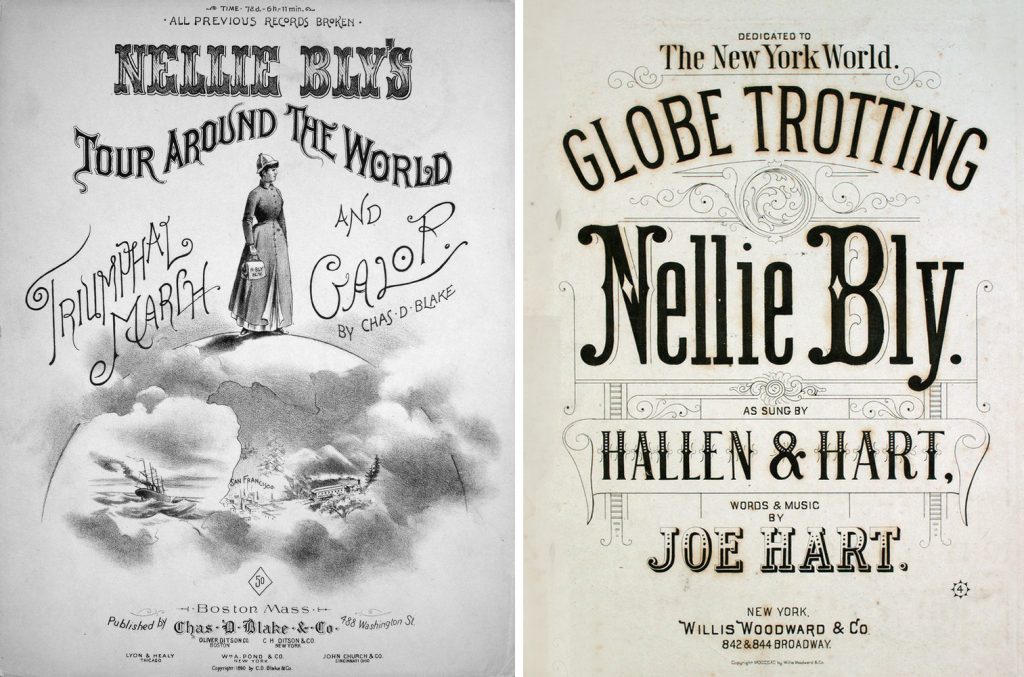

At the end of the 19th century a new type of leisurely traveller made its appearance: the globetrotter. Steamship connections, the extension of railways in the colonies and the opening of the Suez canal shortened the travel time a lot. Of course recreational travel was then an exclusive pleasure for wealthy (European) men. Female travellers had to challenge the notions of their time that travel was unsuitable for their sex. But nonetheless it was a woman, Nellie Bly, who first broke the fictional record set by Jules Vernes’ Phileas Fogg in Around the World in Eighty Days.

Nellie Bly (or Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman) who was an acclaimed reporter at New York World magazine boarded a steamer in 1889 and began her journey. Travelling alone she toured to most of the places that Fogg visited during his journey. She even met Jules Verne when passing through France. Nellie arrived in New York just over 72 days after her departure.

About twenty years later Elisabeth Yates also attempted a record to travel around the world, but this time on foot. Luckily for us her adventure was rather well documented by Clyde Sanger in his story for ‘The Guardian from London’ (December 9, 1959). It goes like this.

Elisabeth or Lizzie was born in Yorkshire UK. After the dead of her mother she sought her luck overseas and emigrated to Canada. There she performed on stage under the name of Elsie Kelsey. She then went to live in America where she met Harry Humphries whom she married. Both keen walkers, they took a ‘short’ honeymoon walk of 4.000 km from New York to Florida and back. It took them two months. It also got Mrs Humphries the attention from the editor of the New York ‘Polo Monthly‘ magazine. It was he who challenged her to walk 48.000 miles around the world in four years. For this she would get a reward of 10.000 dollar. Not worth the candle according to a then journalist. But Mrs Humphries and her husband, who had decided to accompany her, thought otherwise and they started to prepare their journey.

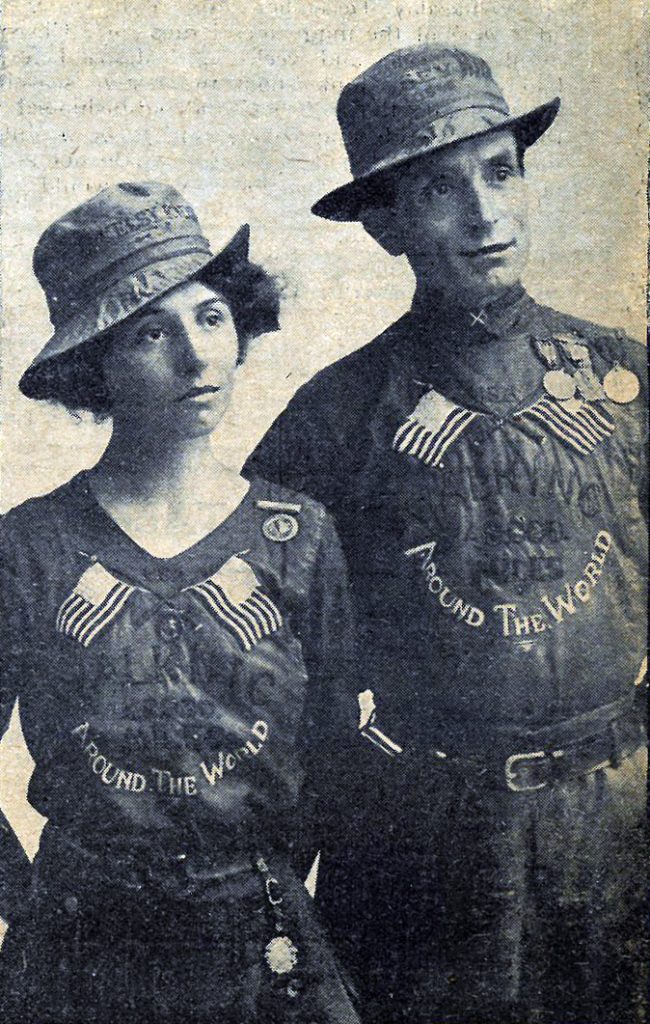

Harry, an embroiderer and tattooist by profession, designed their khaki costumes. Lizzie wore a blouse and skirt, a soft hat and knee-high waterproof walking boots. A knapsack with a sweater and a few necessities completed her outfit. One of these necessities was a revolver. In July 1911 the Humphries couple —or the Kelsey Kids as they named themselves— left New York for Canada. From there they sailed to in England in late November. The two lived on milk and farinaceous food, eating little meat and never drinking water. One of the terms of the wager was that they could only live on hospitality but should not beg, borrow or steal. To finance their journey they gave lectures. In January the couple arrived in Manchester. There Harry had a ‘nervous breakdown’ and returned to America. The truth is, he ran away abandoning Lizzie and their round-the-world walking tour, taking all of their money with him.

Our Lady Globetrotter though continued her voyage, this time accompanied by a dog as a more loyal companion. She wanted to show that women dare to walk “in all kinds of weather, day and night and in countries whose language they cannot speak.”

Lizzie had planned to walk across Africa, Asia and Australia. She would then sail to South America and travel northwards back to New York. But her plans came to nothing. For two years she kept walking back and forth across Europe. The reason for this is that Lizzie had engaged an agent, and the course of her journey depended on the contracts he could sell. By then she enlivened her lectures with films about her walks.

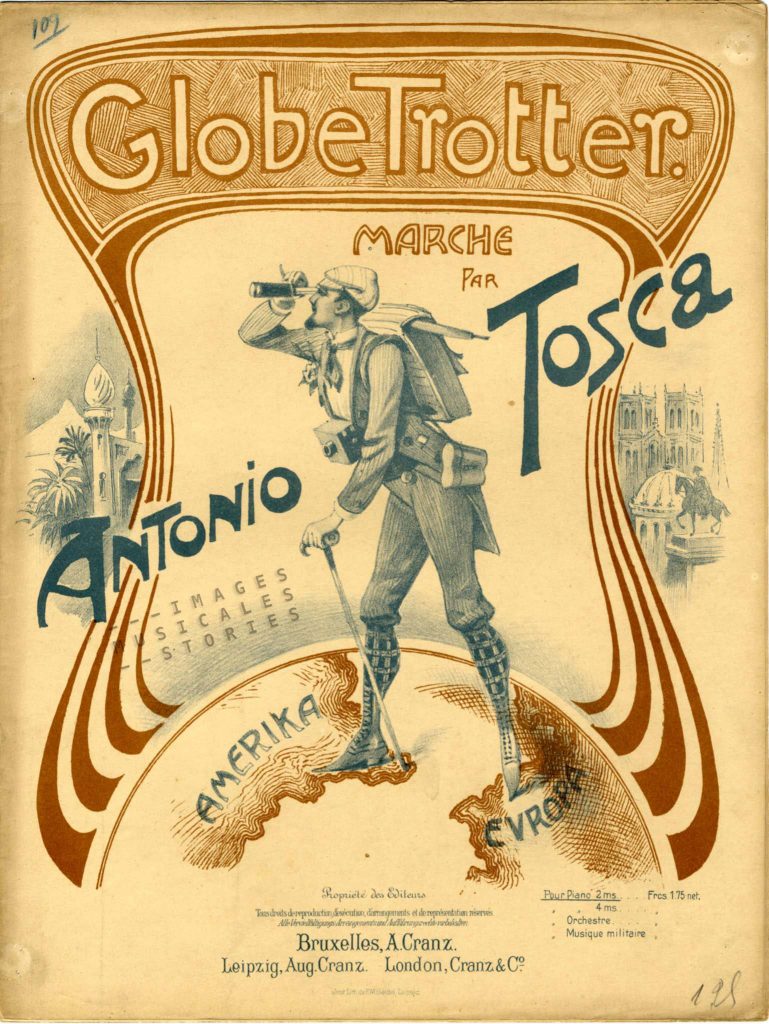

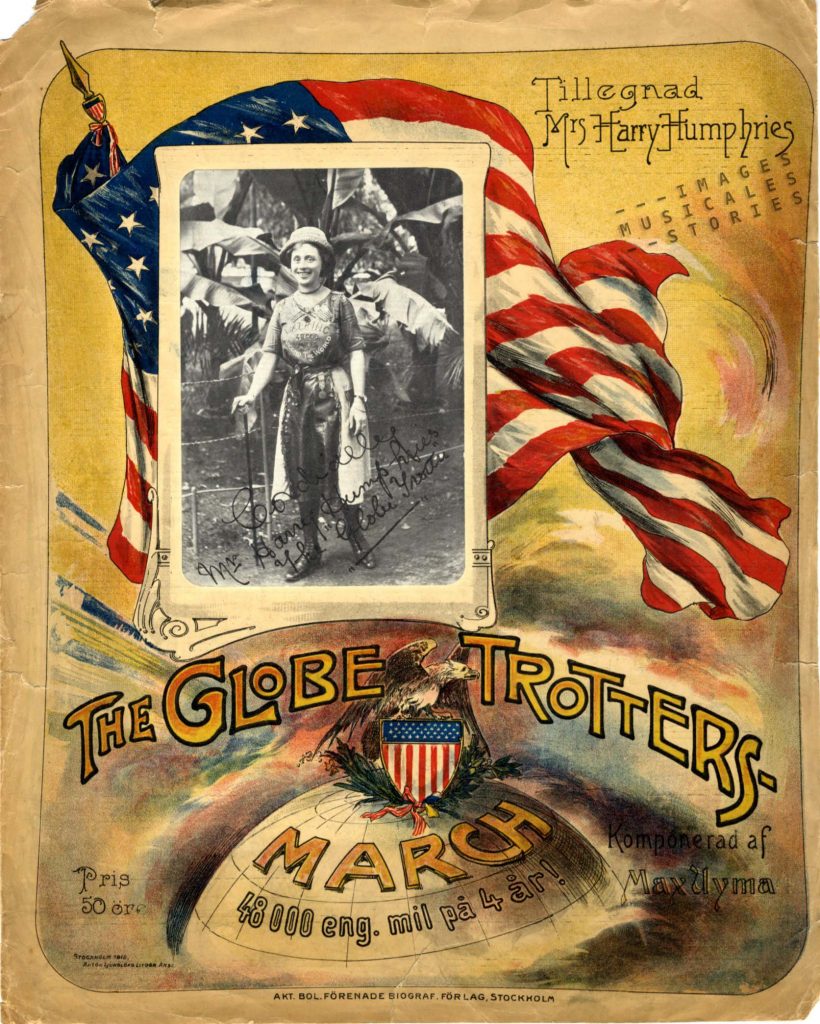

The sheet music The Globe Trotters March was published while Lizzie was walking in Sweden in 1912. The following film from 1913 shows Lizzie in Düsseldorf. The cheerful man with his practical jokes, is believed to be her agent.

When the Great War broke out, Lizzie was still in Düsseldorf and had to leave her trunk full of memories behind and flee from Germany. She had ‘only’ walked 10.000 miles, so she did not fulfil the wager and did not get the $10.000 prize money.

A few months later, in 1914, she walked 5.000 miles from New York to San Francisco. Her aim was to gather funds for the benefit of the Red Cross on the battlefield of Europe. This shows that our Lady Globetrotter had the heart in the right place.

We cannot but think that when her scoundrel of a husband Harry deserted her, she might have found solace from Nancy’s vengeful words…