We are thrilled with this post. For years we couldn’t find any information on the illustrator Wolfgang Ortmann (1885-1969). But here it is: the first sketch of his life and work.

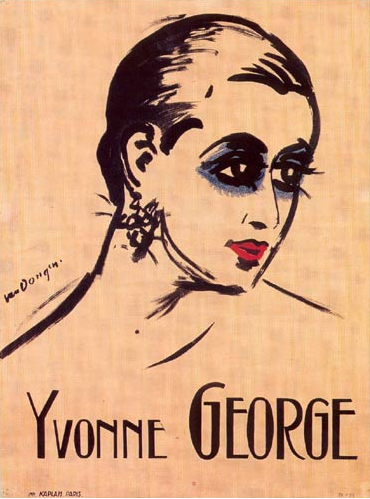

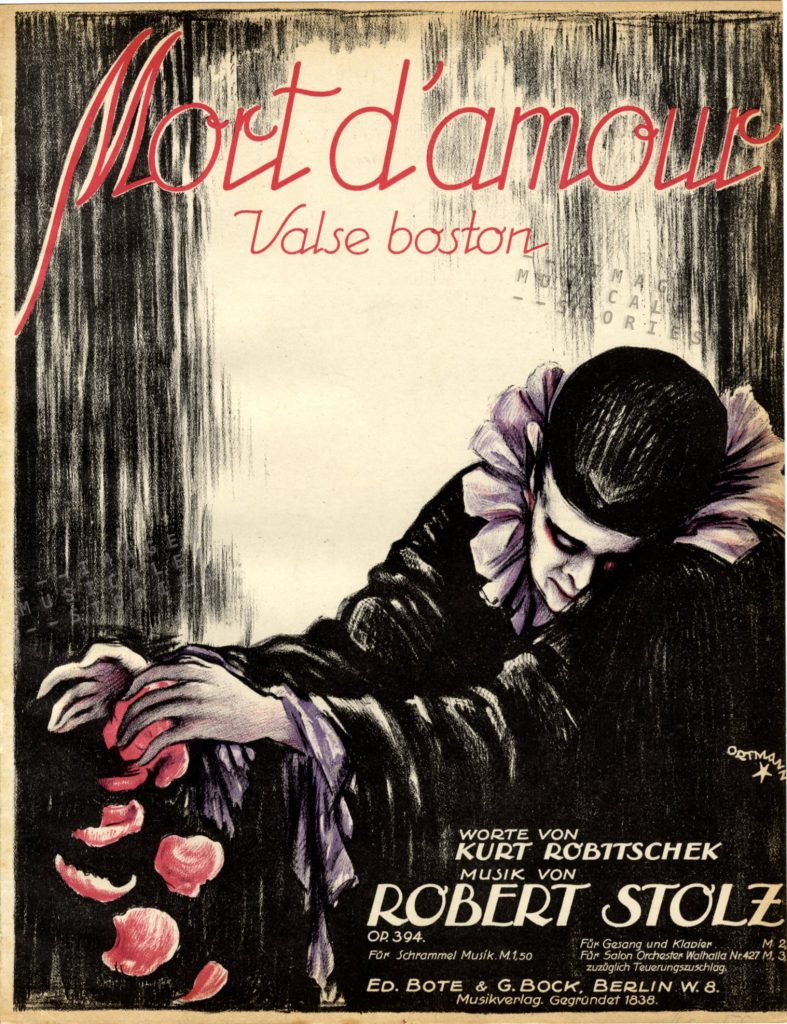

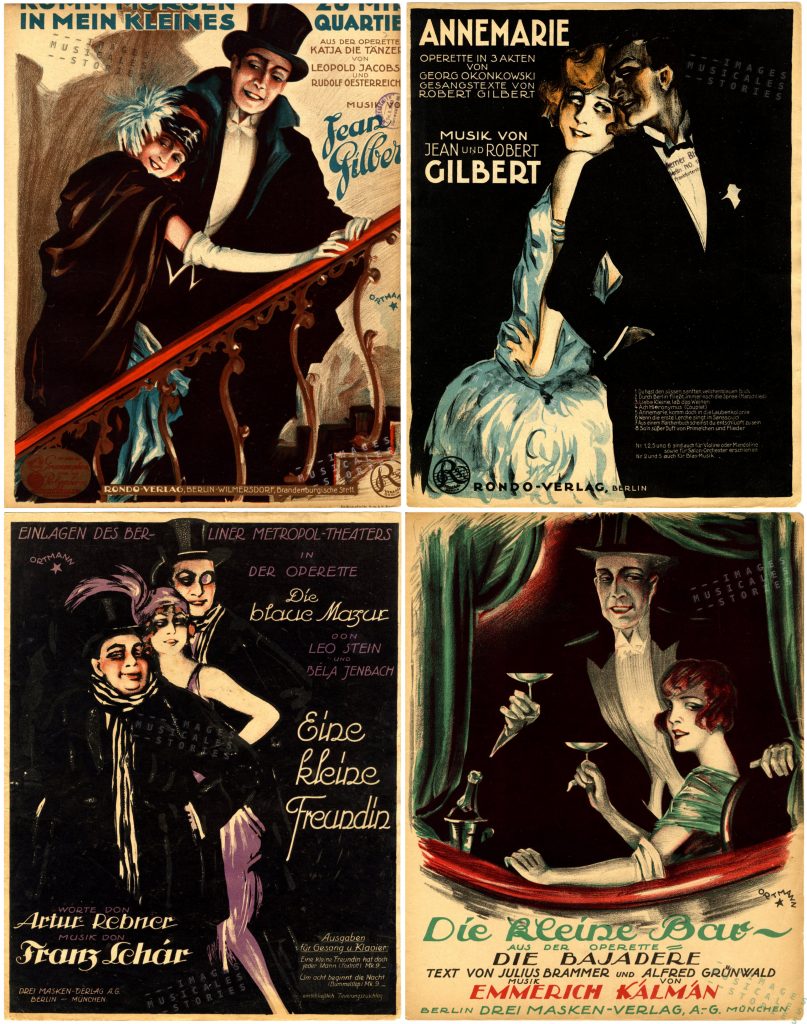

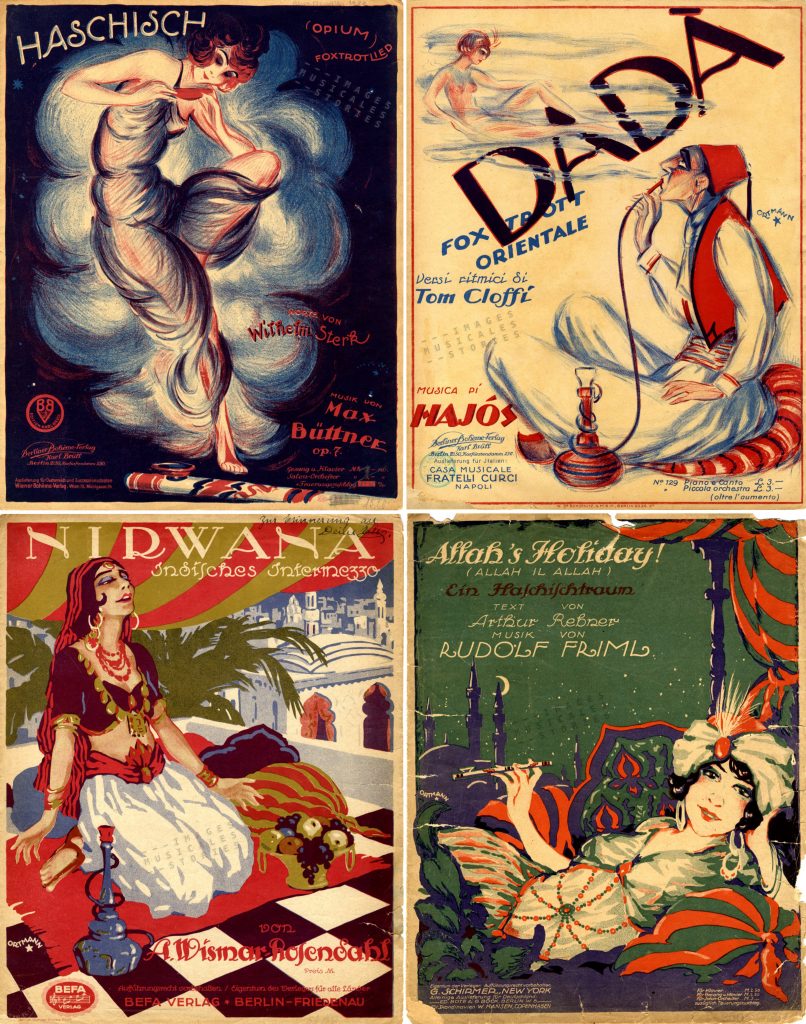

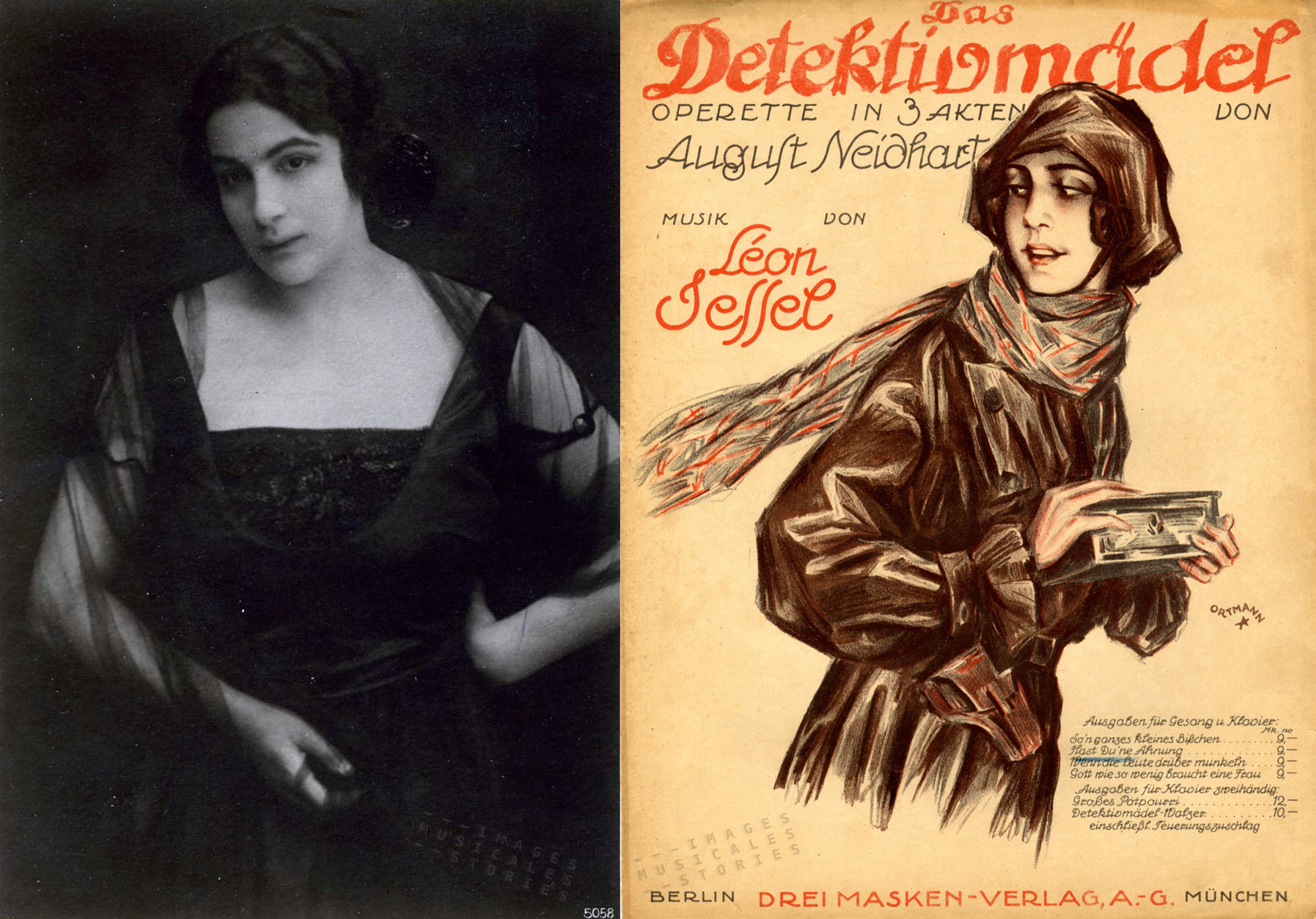

The covers by the German illustrator Wolfgang Ortmann carry his trademark: a wavy signature above a single small star. His drawings are bold, with a dynamic composition and imaginative colours.

Ortmann doesn’t hesitate to use black and dark shadows to add a touch of drama. His images reflect the Roaring Twenties in Germany: ladies with bobbed haircuts (Bubikopf), heavy mascara, hairbands, cocktail dresses or fur, and elegant (older) men in evening dress. We are witnesses of nightlife scenes in cabarets, intimate bars, parties with jazz and champagne, theatre loggias, dark alcoves and shadowy staircases.

Many of his covers illustrate popular exotic themes and oriental cliché fantasies.

Finally, the essence of Ortmann’s covers is every so often sexual. His illustrations for many foxtrots and lieder breathe seduction, temptation, passion, flirtation, swooning and sensual ecstasy.

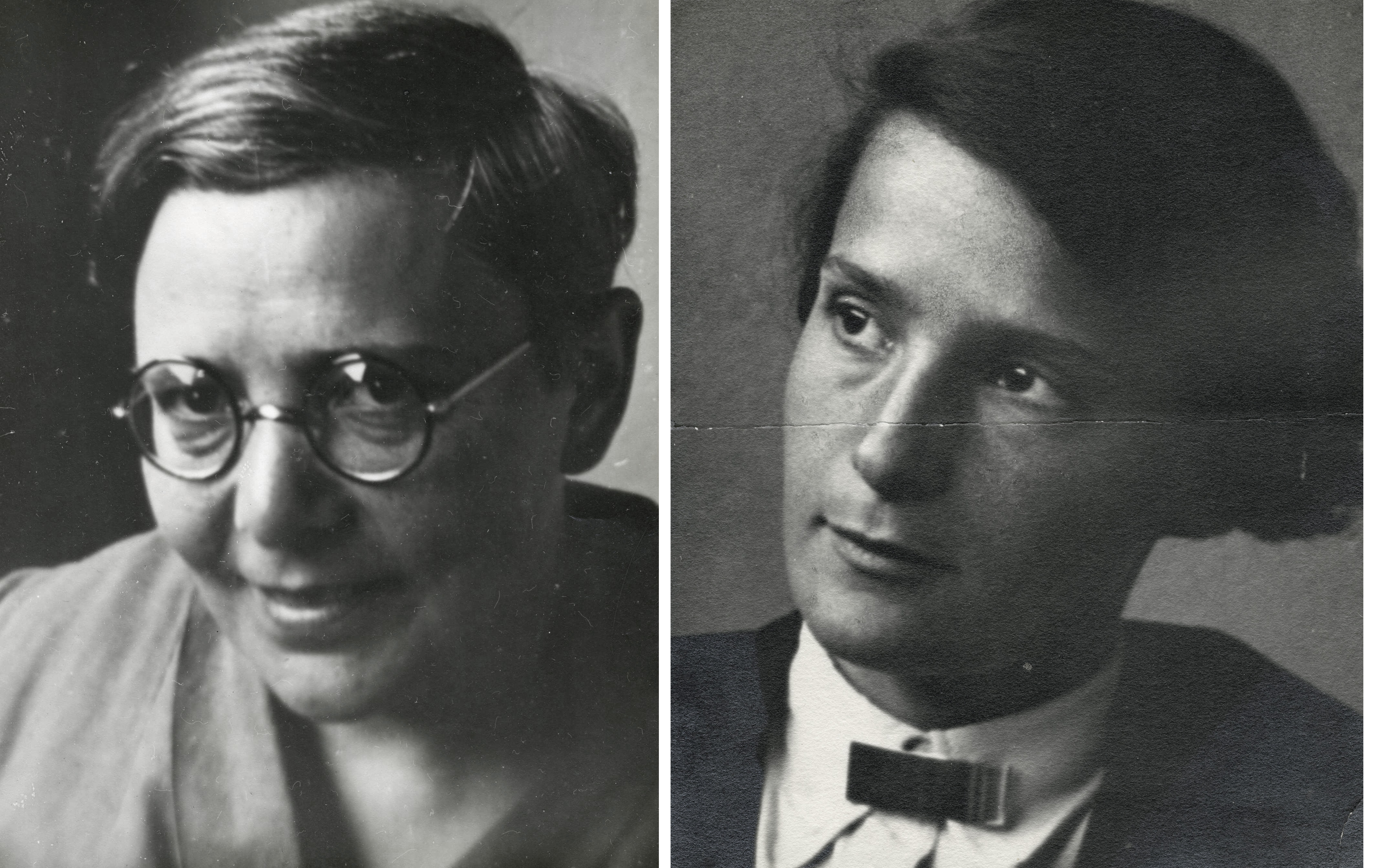

Ortmann is the most prolific of all German sheet music illustrators, closely followed by Willy Herzig and Paul Telemann. In our collection, all of Ortmann’s music covers were designed during the five years following the First World War (WWI). The information about Ortmann’s life and the photos come from his grandson Peter Crane of Seattle. He told us that before WWI the young Ortmann created advertisements and posters for the gas company. At the Sammlungen Online of the Wiener Albertina one can see proof of his graphic talent at the age of twenty-five. The quality of his posters rivals with the Plakatstil creations of illustrious designers Lucian Bernhard, Ludwig Hohlwein, Julius Klinger and Hans Rudi Erdt.

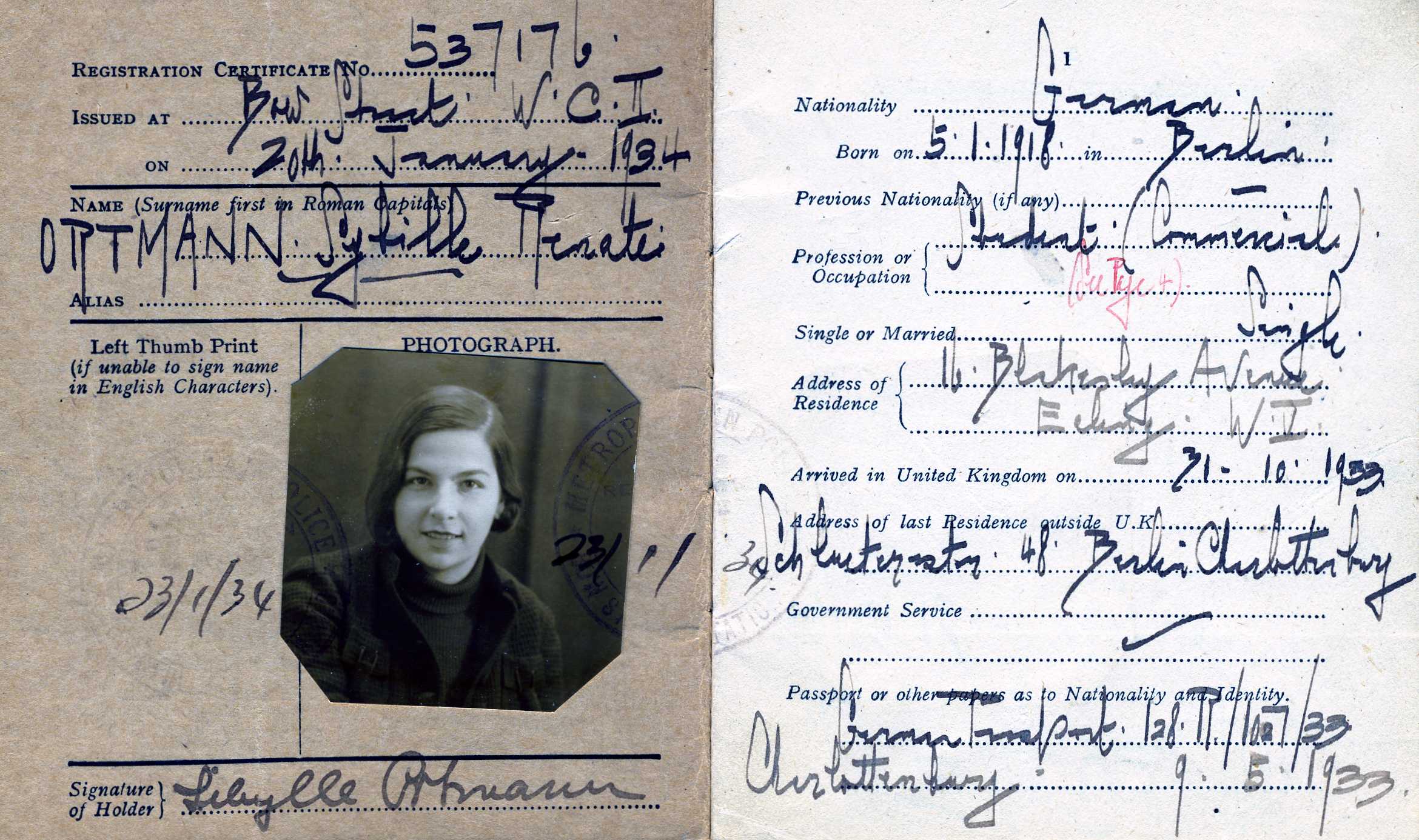

Before or at the outbreak of WWI their marriage broke up. Years later, when Hitler came to power, Ortmann’s ex-wife Rika had every reason to flee Germany because not only was she Jewish, but also a communist. In 1933 she moved to Russia with her daughter Muschi.

A couple of years later Muschi left Moscow for London, married and immigrated with her husband Fritz Daniel to America in 1936. In that year her mother Rika fell victim to Stalin’s Great Purge and was isolated from her family, unable to receive nor to send letters. She was sentenced to eight years imprisonement. But before the end of that term, in 1941, she was shot by the NKVD (The People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs) in the mass murder of 157 political prisoners and buried in the Medvedev Forest.

(read more on Rika Baruch here)

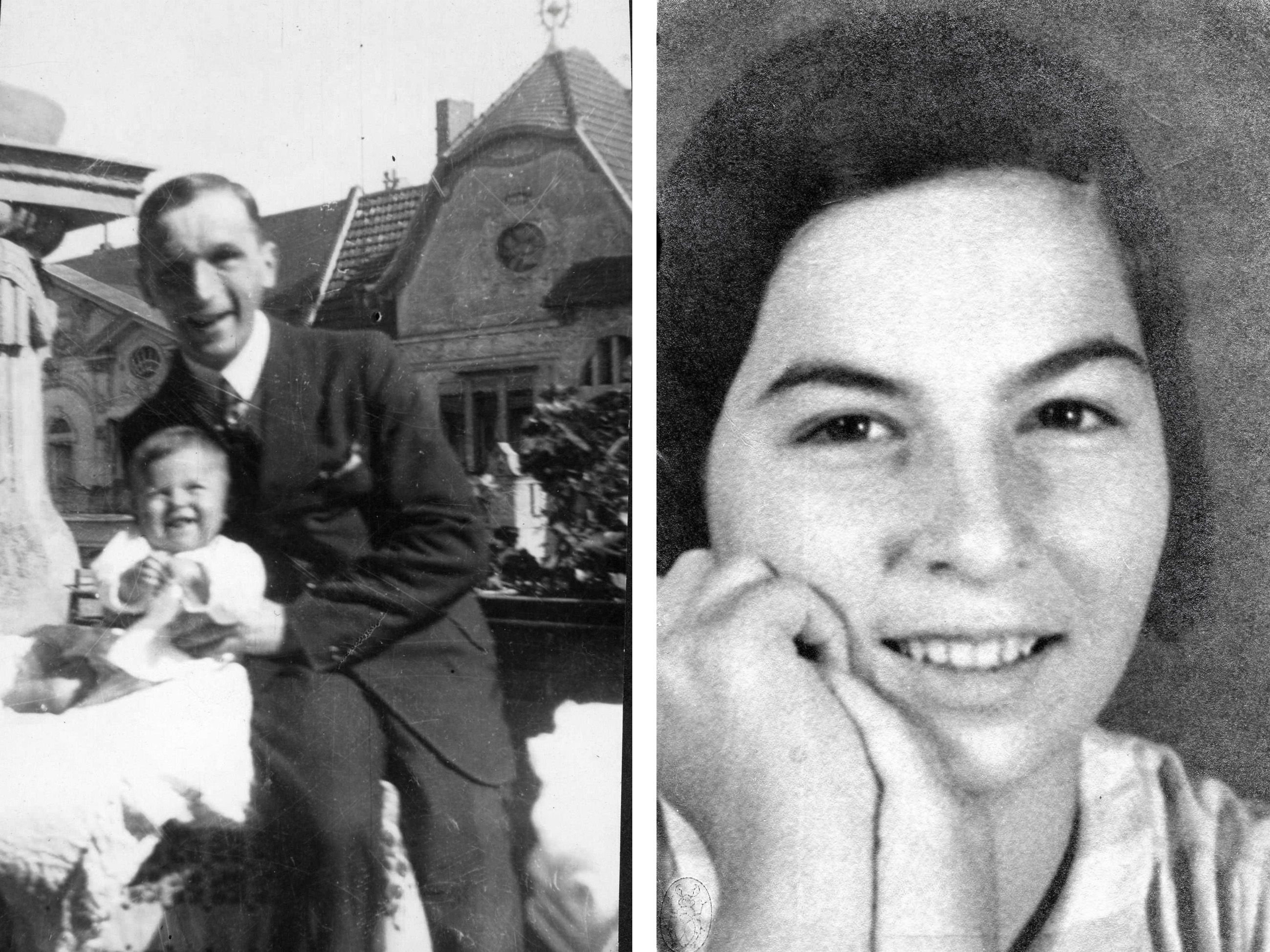

Already in 1915 Ortmann met his second wife Eva Löwenfeld (1895-1988) and married her a year later. At the end of WWI, Eva and Wolfgang got a daughter and named her Sibylle. One or two documents from archives seem to suggest that during the war Ortmann served in the army as a reporter artist, illustrating battles and drawing maps.

But also the marriage with his second wife Eva, a professional singer, ended soon. Eva was offended and probably disgusted by Ortmann’s attraction to young girls, as she had discovered him with one of them. This episode is described in the memoirs of Eric Godal (Kein Talent sum Tellerwäscher) who at that time, ca 1920, was an assistant in Ortmann’s atelier. So, at 26, Eva left her husband to go live alone with her daughter Sibylle in Charlottenburg in poor circumstances.

She later remarried the singer Fritz Lechner. In 1936 Eva and Fritz fled the Nazi’s and immigrated to New York. A year later Sibylle joined her mother. The correspondence between Sibylle and her mother over the years 1932-1946 form the core of a book that Peter Crane published about the German-Jewish emigration background of his mother and grandmother: Wir leben nun mal auf einem Vulkan (Weidle Verlag, Bonn – 2005).

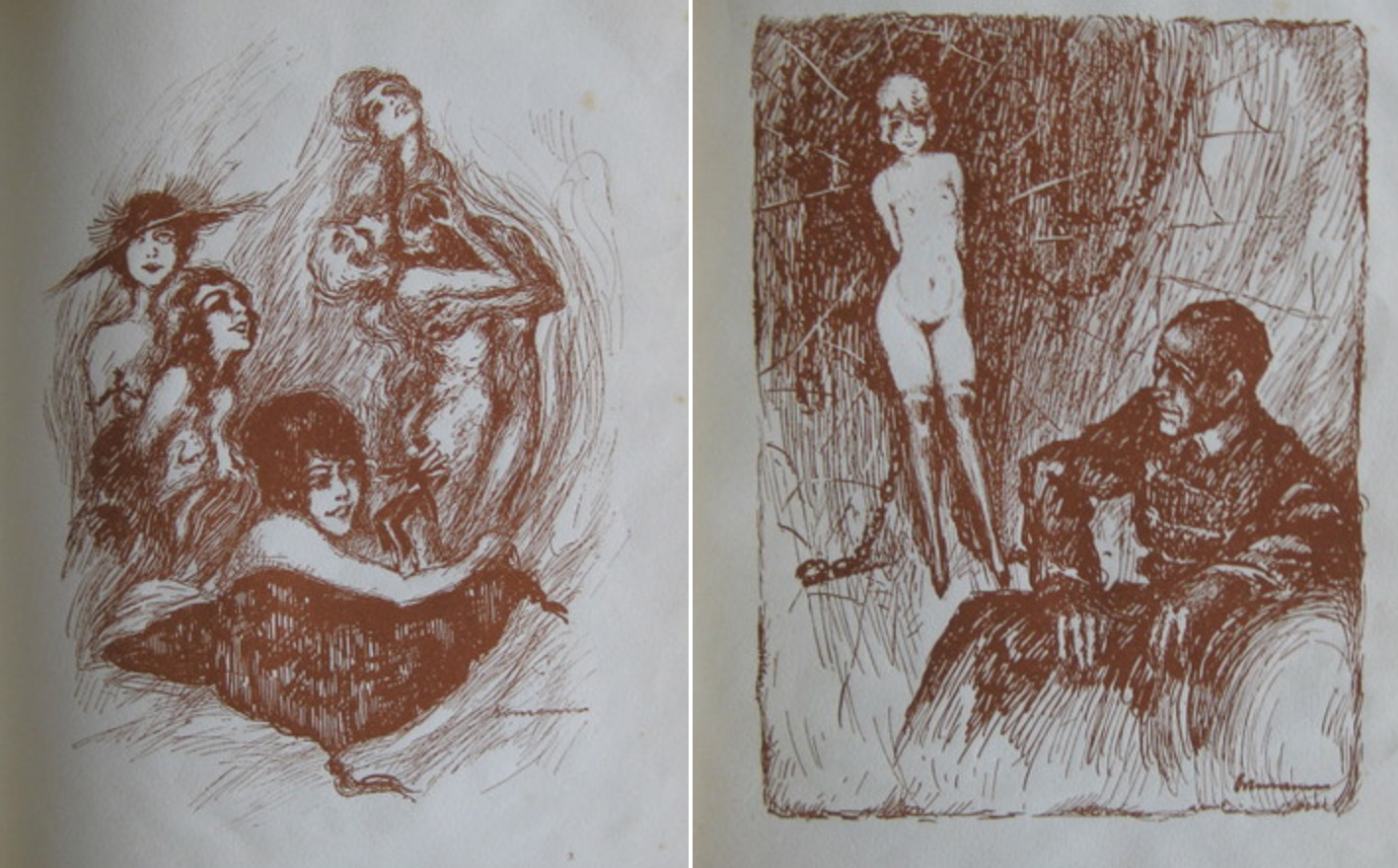

In 1919 Ortmann illustrated the book Das Brevier des Junggesellen with numerous erotic drawings.

His work didn’t pass unnoticed. Max Brod, a close friend of Kafka, admires the artistic skills of Ortmann in his poster for the 1920 operette Wenn Liebe Erwacht. In his novel ‘Die Frau, nach der man sich sehnt‘ Brod spends a page and a half to praise the image, which he thinks captures the essence of Berlin at that time.

A totally different work is Ortmann’s 1920 poster design for the Deutsche Volkspartei depicting a mother holding high her child. Rudolf Hess liked this poster so much that he sent a copy to his parents as a keepsake. And then there is this 1933 or later poster ‘Dein Einsatz‘ for the Volksbund fur das Deutschtum Im Ausland, a cultural public relation association of the National Socialists.

Ortmann married a third time (we don’t know with whom nor for how long – see Heidi Reichhold’s and Peter Crane’s comments hereunder…) and spent the end of his life with his fourth wife Grete. We see them together in a picture taken in Berlin in 1966 when Peter Crane visited his grandfather after having looked him up in the telephone book. Ortmann is then already over 80 years old. He died a few years later. Until now we haven’t found any post-WW2 art work by Wolfgang Ortmann.

Peter Crane wrote to us: “When Hitler came to power, Ortmann made busts of Hitler, Goering, and Goebbels and displayed them in a department store window in Berlin. (…) But because of his Jewish wife, he could not be admitted to the Reichskulturkammer, and I think his work for the Nazis dried up.” The Nazi pressure on Aryans to leave their Jewish wife was immense. But Ortmann stayed with his wife and did not desert her. Grete had to do forced labor in a munition factory but she survived the war (unlike her sister who was murdered in Auschwitz). She also endured the ‘liberation’ of Berlin, as Peter Crane chillingly accounts: Grete Ortmann said to me, speaking of 1945, “And when the Russians came, they took ALL the women.” She looked deeply into my eyes as she said that, so that I would understand that she was referring to herself…