We focused previously on Hugo d’Alési as a painter, illustrator and inventor of the Maréorama. Besides, as a young man Hugo d’Alési was drawn to spiritualism or the belief that the dead can communicate with the living. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries it was not so exceptional for people to attend seances where a medium claimed to contact the dead. Victor Hugo, to name but one, was also known to dabble in this macabre divertissement.

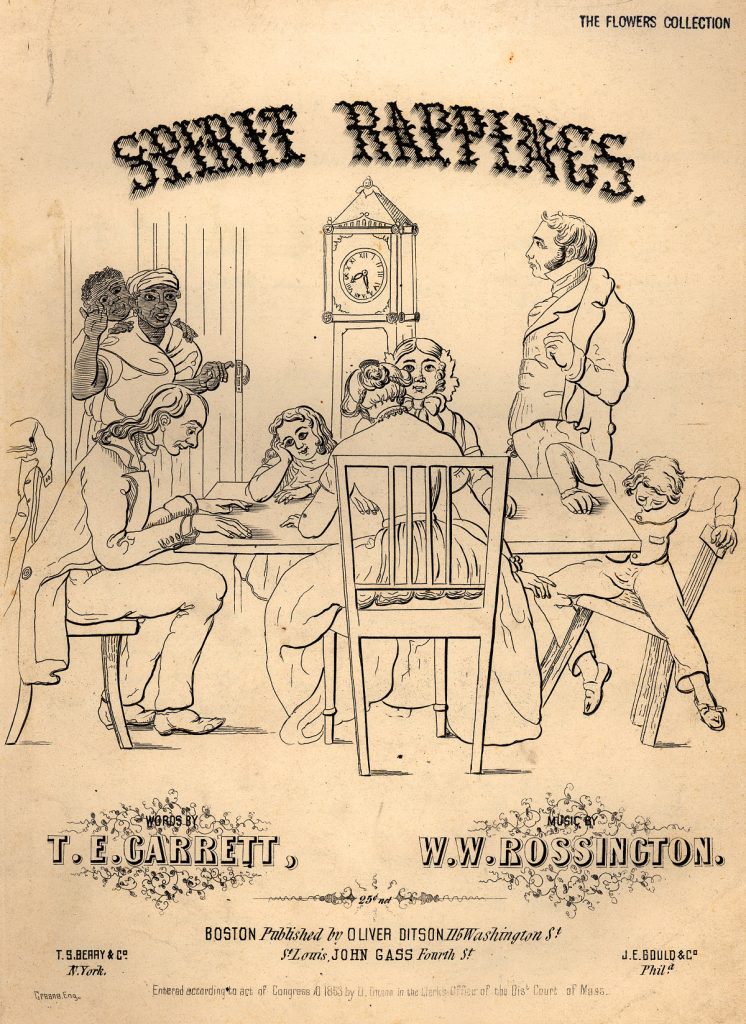

The origins of modern spiritualism have been traced to the Fox family in Hydesville, New York. In 1848 the two youngest Fox daughters reported hearing a series of raps on their furniture and bedroom walls. They claimed that these rappings were communications from spirits. Although many years later they confessed to the hoax, their public demonstrations of rappings and the seances of hundreds of imitators gave rise to a widespread interest in spiritualism.

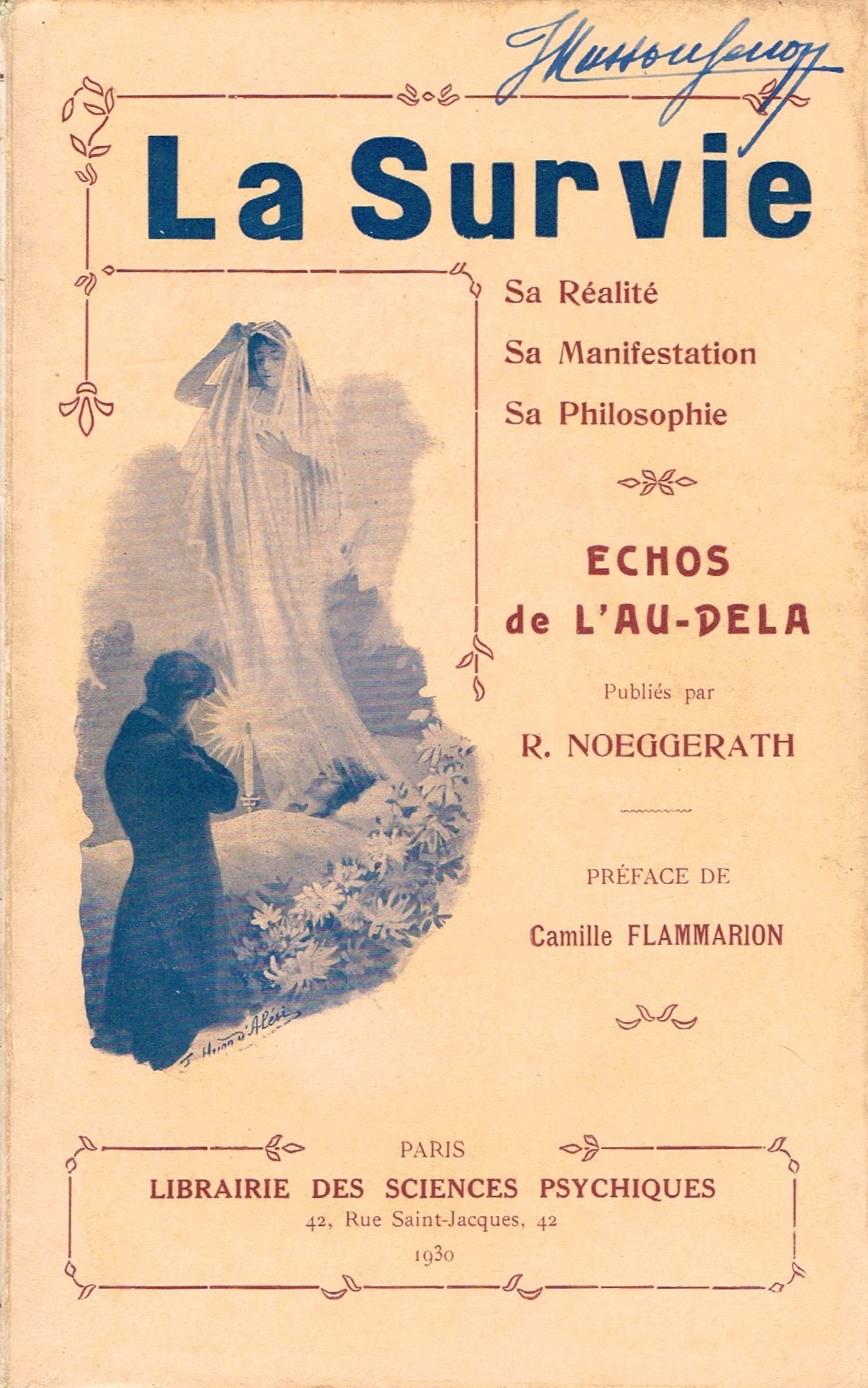

Marie, the first wife of Hugo d’Alési, passed away when he was only 32. In her lifetime she had posed as a medium who automatically wrote down poems dictated to her by spirits. And Hugo d’Alési himself was able, without looking at his paper, to make drawings of spirits, who he insisted were present during seances. The couple had been guided into spiritism (the French branch of spiritualism) by Rufina Noeggerath who was born in Brussels in 1821 but later lived in Paris. There she held a salon for artistic and philosophic followers of spiritism.

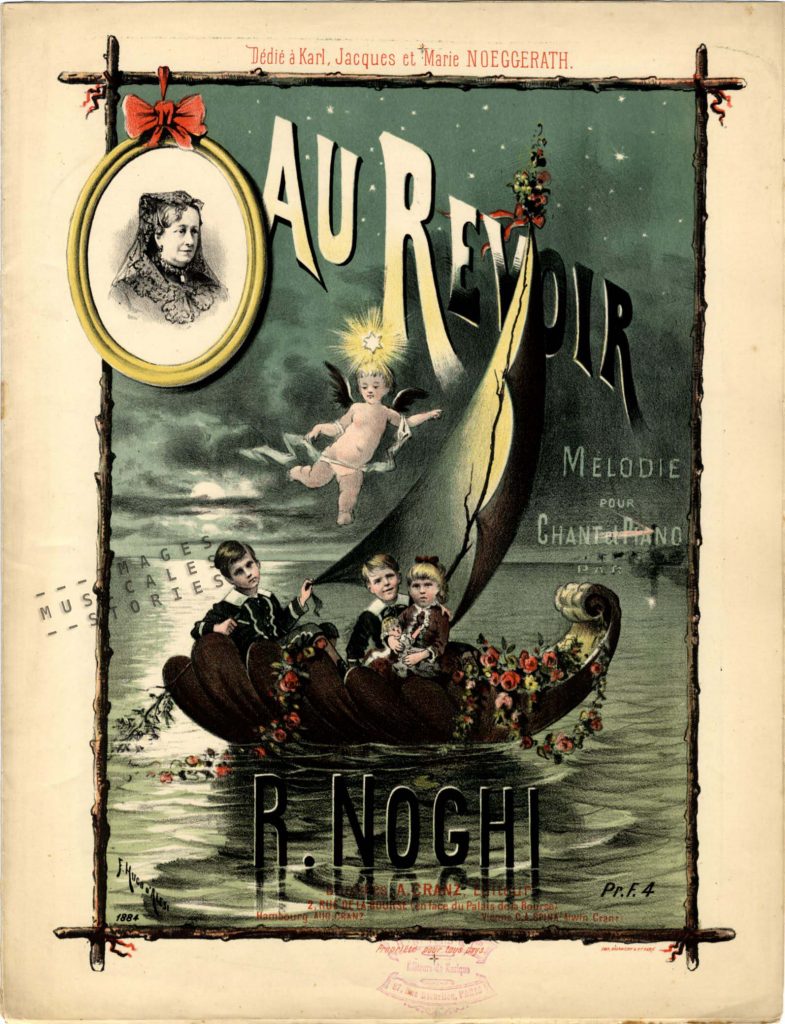

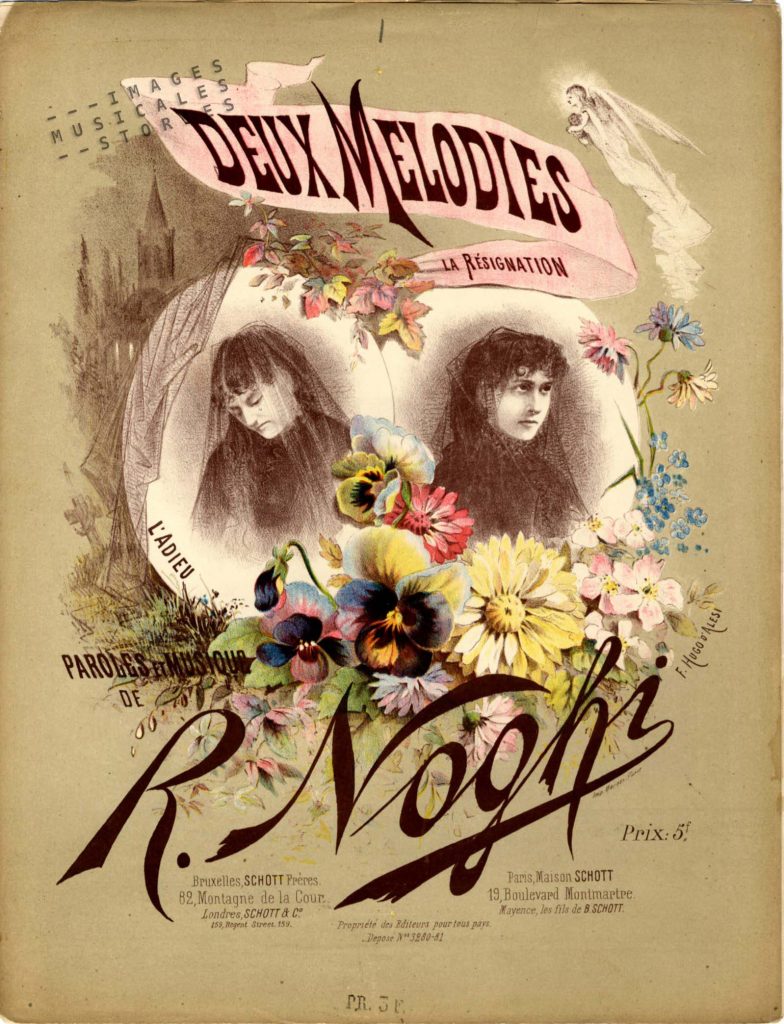

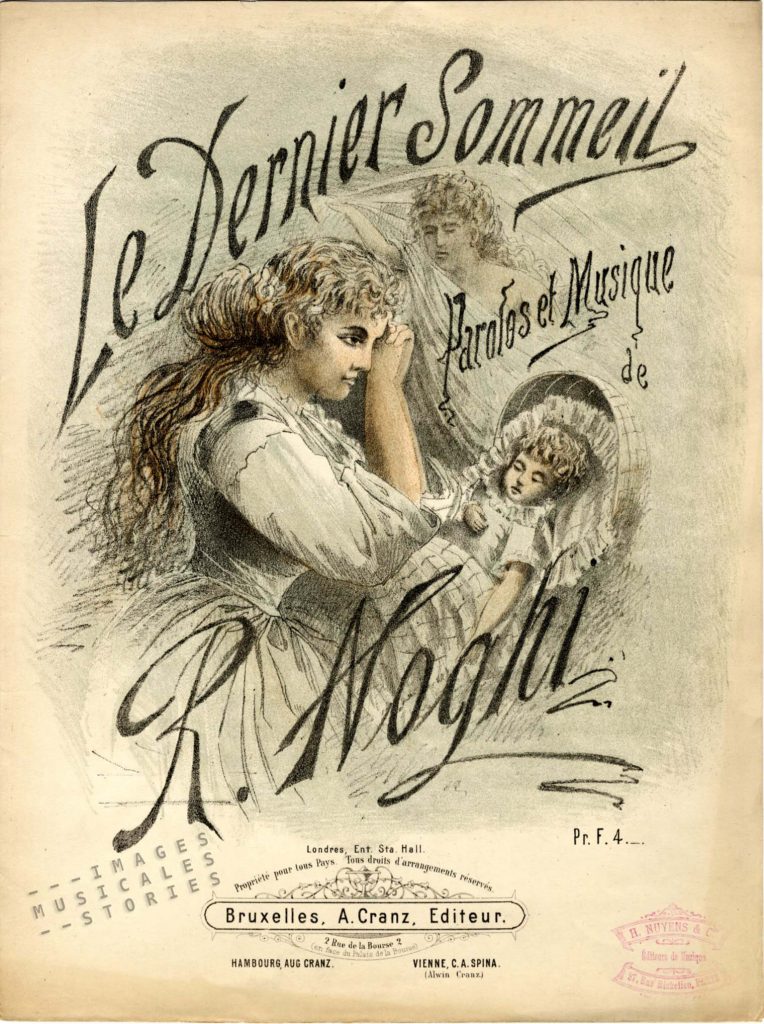

The song Au Revoir illustrated by d’Alési is dedicated to Karl, Jacques and Marie Noeggerath. The woman in the medallion is Rufina Noeggerath and she seems to be in mourning. The gothic image depicts three children in a flowered sailboat. It looks to me that Hugo d’Alési perfectly demonstrated the transition of three persons close to Rufina from this world to the next, with guardian angel, flower wreaths, black sail e tutti quanti. We have two more songs created by R. Noghi in our sheet music collection. All three covers share a gothic illustration of grieving about children lost. Though we still have to find proof, we can safely assume that R. Noghi is the pseudonym for Rufina Noeggerath.

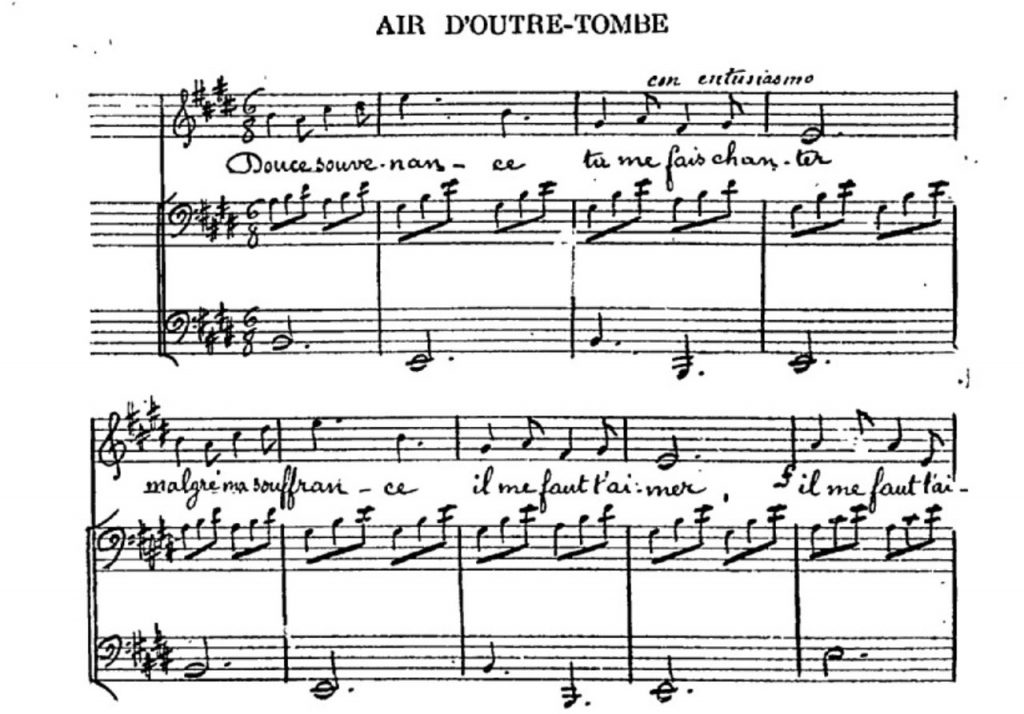

Rufina Noeggerath not only held literary and spiritistic salons in Paris, she was a medium herself. Once she sat at a small round table together with Jacques Offenbach‘s nephew when all of a sudden Offenbach’s spirit started to talk to them. Well, kind of talking, the table leg tapped out the messages: one tap meant a, 26 taps meant z. After some chitchat Offenbach started to compose a melody called Air from beyond the grave.

Rufina then asked Offenbach what words should accompany the melody. “Choose the most suitable one in your bundle of mediumistic poems written by Marie d’Alési.” the table answered. Rufina did what was asked and the table approved. Rufina claimed that she was not allowed to disclose the identity of Offenbach’s nephew, so conveniently, the story could not be confirmed and maybe she wrote this little melody herself.

This 1906 British short film features a medium exposed as a fake during a seance. The mechanisms of the special effects are revealed when the light is switched on (at around 3:25).

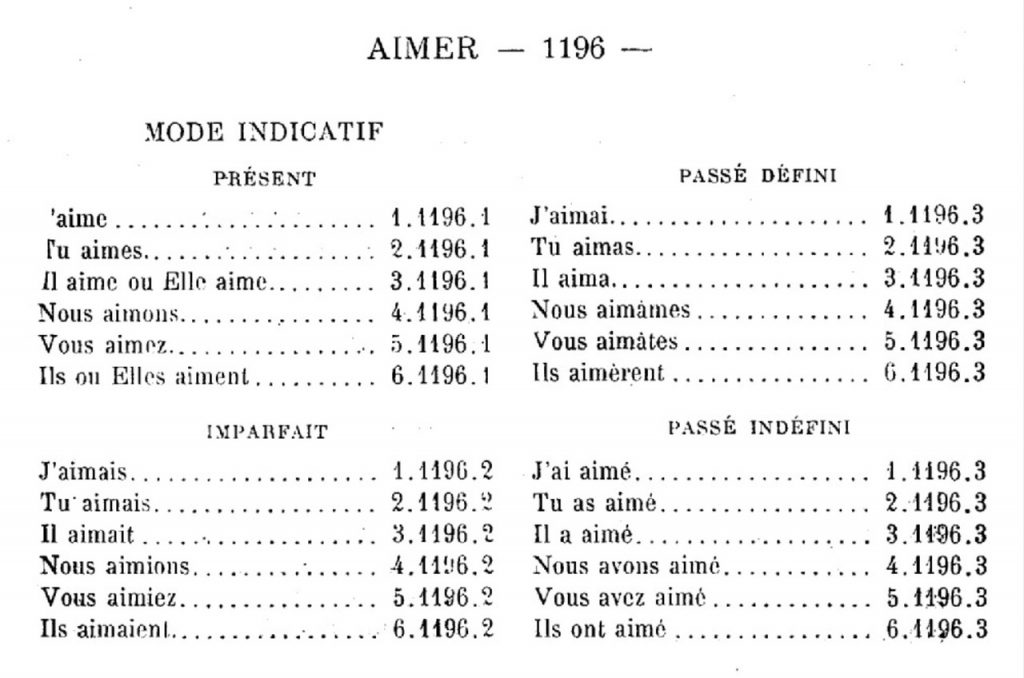

Hugo d’Alési was not only an engineer, a gifted illustrator and a spiritist, in 1901 he also wrote a method for international correspondence by numerical language. His universal language used nothing but the ten numerical digits: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9 and the letter x for indicating the plural. The language should enable everybody to exchange letters with the whole world without knowing any foreign language. All you needed was a french-numerical, english-numerical or japanese-numerical dictionary. The conjugation of verbs was also indicated by digits. Needless to say that his method never became successful nor popular, and I don’t think any numerical dictionary was ever printed. Surely his promotion of a numerical Esperanto made less waves than his Maréorama in the real world. But perhaps it became more accepted in the afterlife…

vous êtes formidable !

j’adore votre manière d’explorer, d’exploiter la couverture de ces partitions d’une autre époque

continuez !

JF B