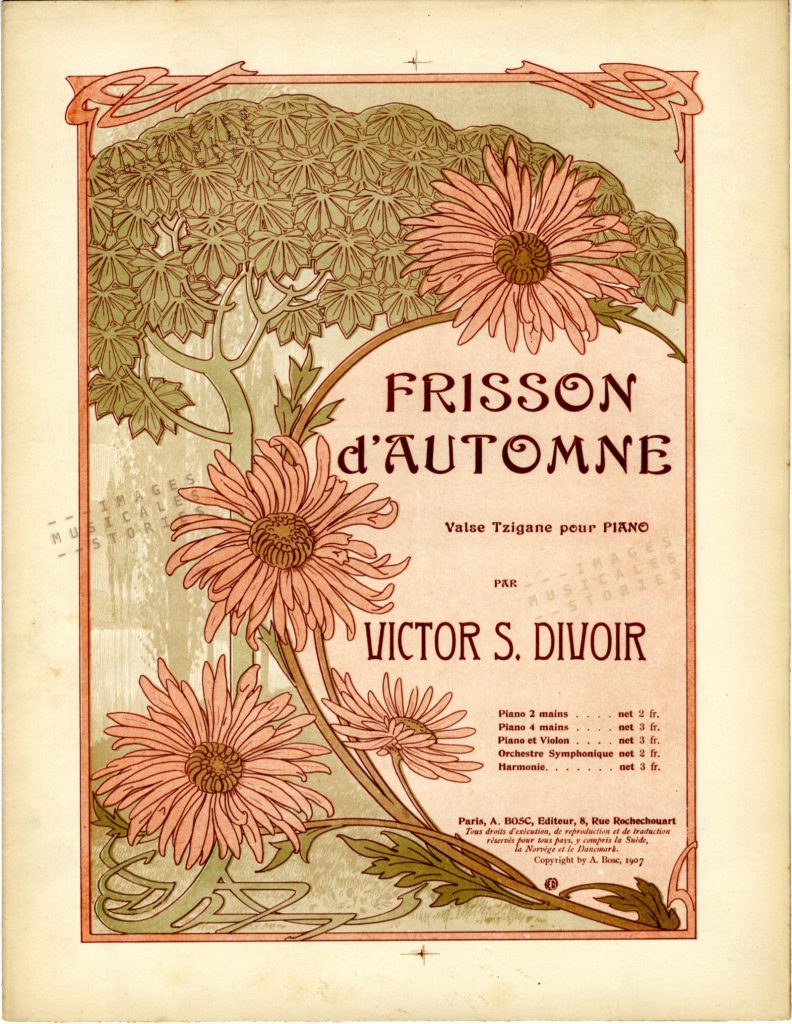

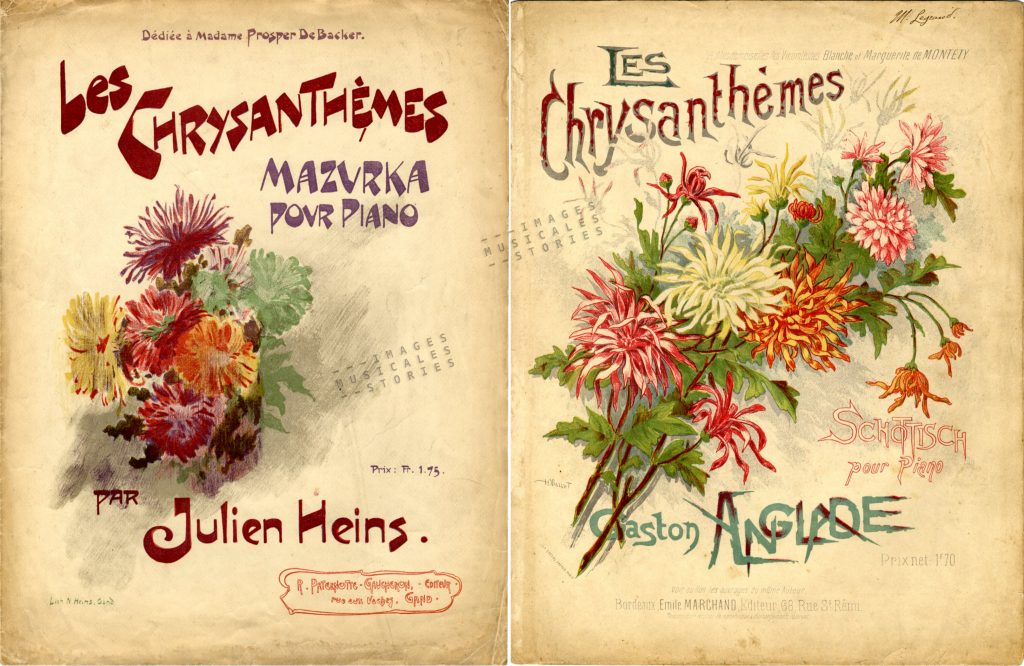

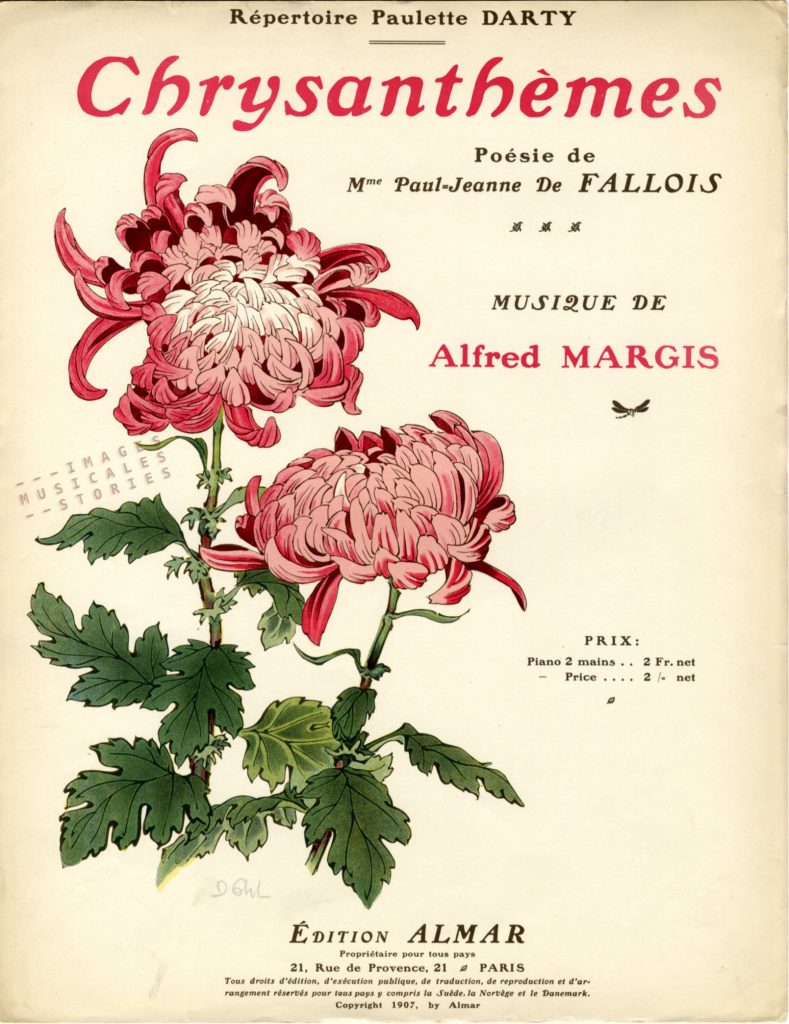

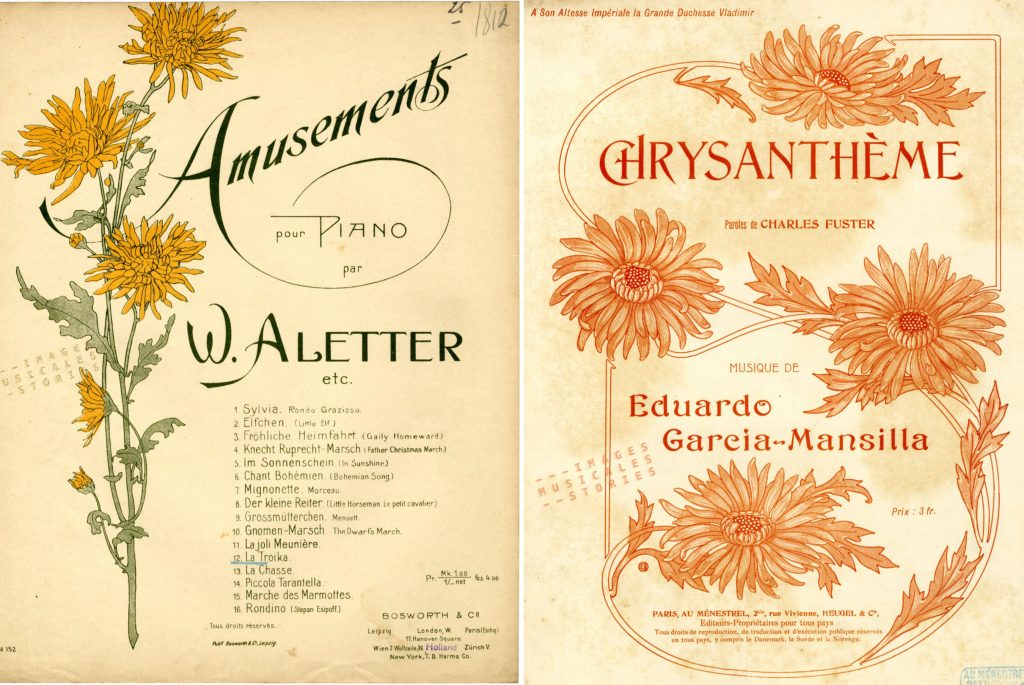

Inspired by autumn I scanned our collection for chrysanthemums. And look what I found: no less than a dozen covers! That doesn’t come close to the number of sheet music romantically decorated with roses. But at least it shows that in the beginning of the 20th century mums (the informal name for cultivated chrysanthemums) were cherished. Perhaps because they seem to add a touch of exuberance to the music?

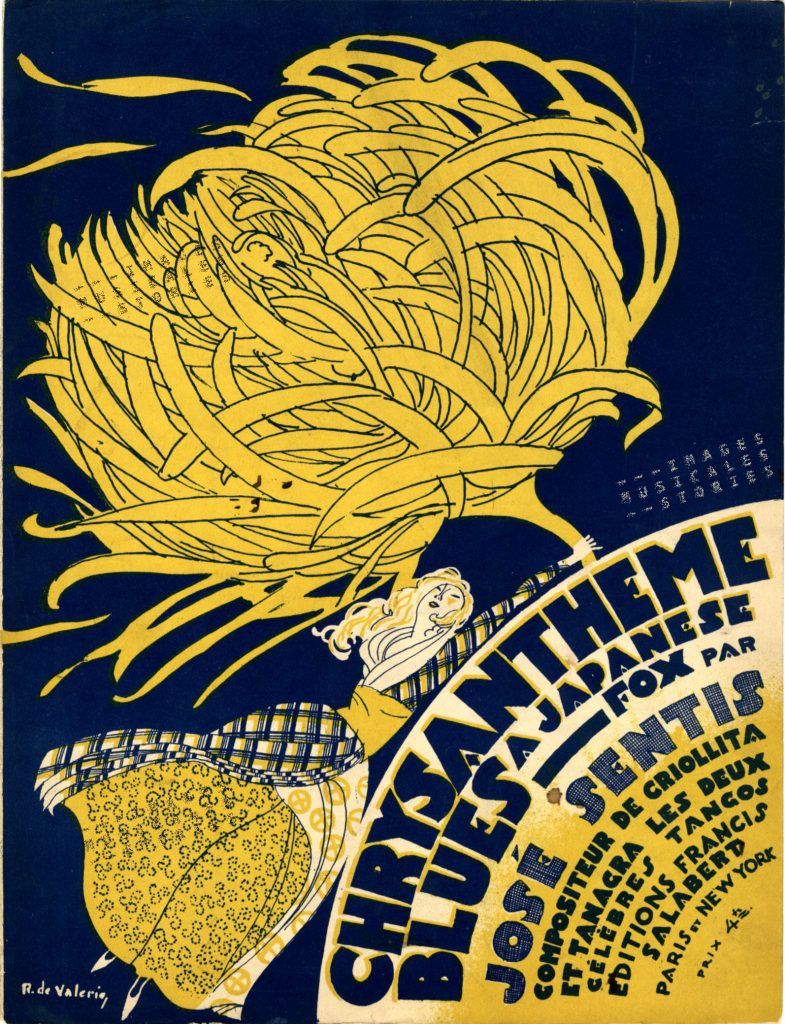

Chrysanthemums are botanically described as a genus of compositae with more than 200 species. The variety of colours and wildly arranged petals often reminds one of small fireworks.

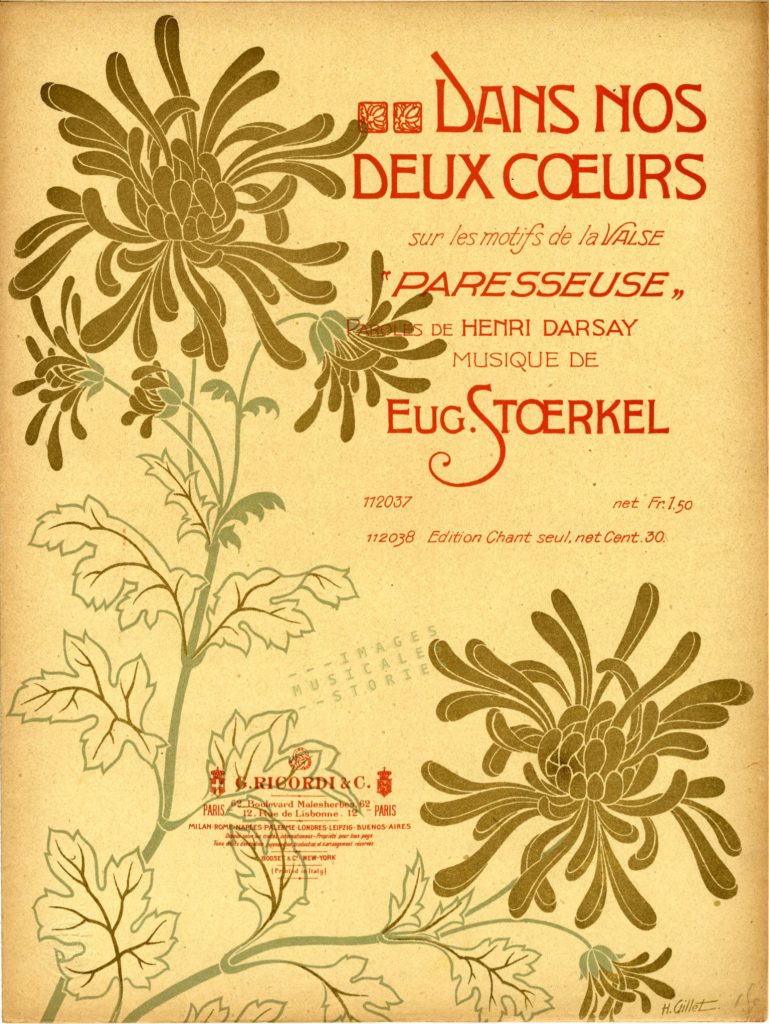

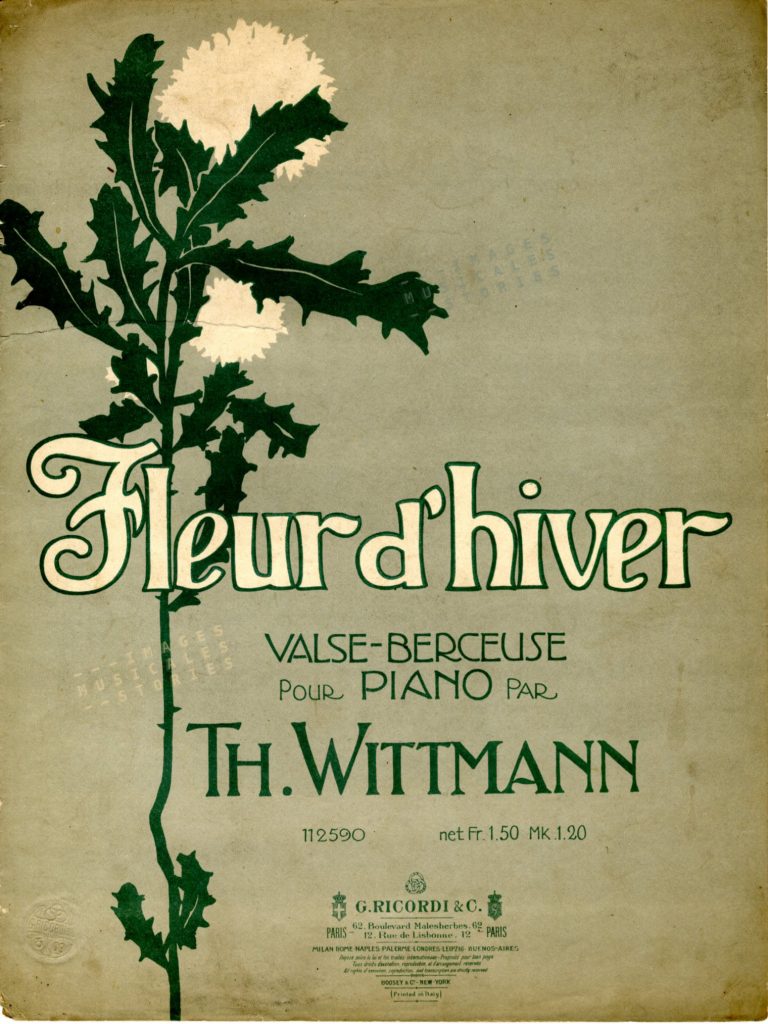

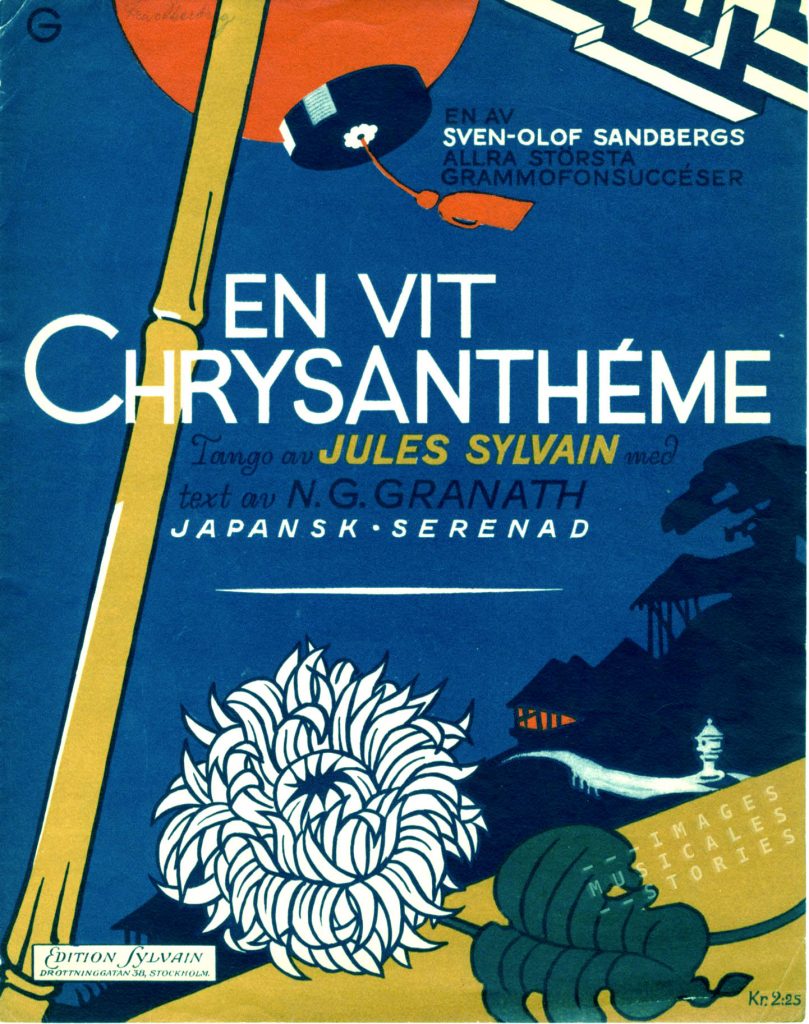

It is probably their Chinese origin (and centuries later also Japanese roots) that explains their highly decorative value for many orientally inspired art nouveau images.

Twenty years later, art deco artists showed no lesser fascination for the orient. Look at de Valerio’s beautiful cover design for ‘a Japanese fox‘ or Granath’s Swedish illustration for a ‘Japansk serenad‘.

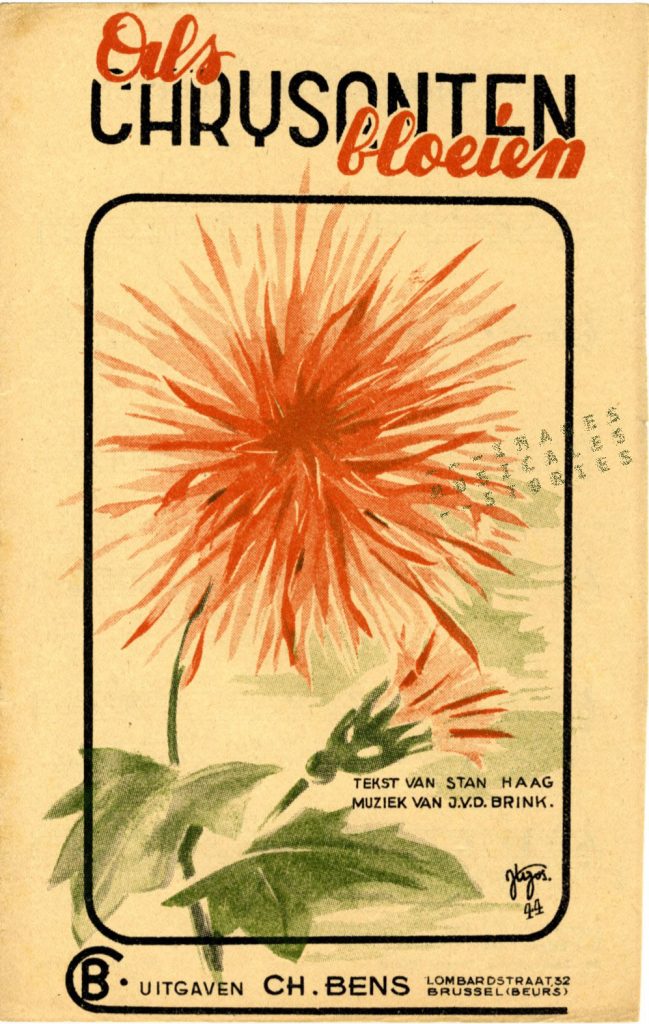

As a finale, here is one more sheet music: charming, though I’m not really sure that it is an ‘official’ chrysanthemum…

I was surprised to learn that one can brew tea from certain chrysanthemum flowers. For centuries it has been a popular drink in China and other parts of the world. It is praised for its floral aroma and health benefits.

Chrysanthemums have also been used in the Chinese kitchen and in medicine. The flower heads of two particular species have traditionally been used in the Middle East and the Balkan as a repellent for insects. This effect is caused by the toxic substance pyrethrum which they contain.

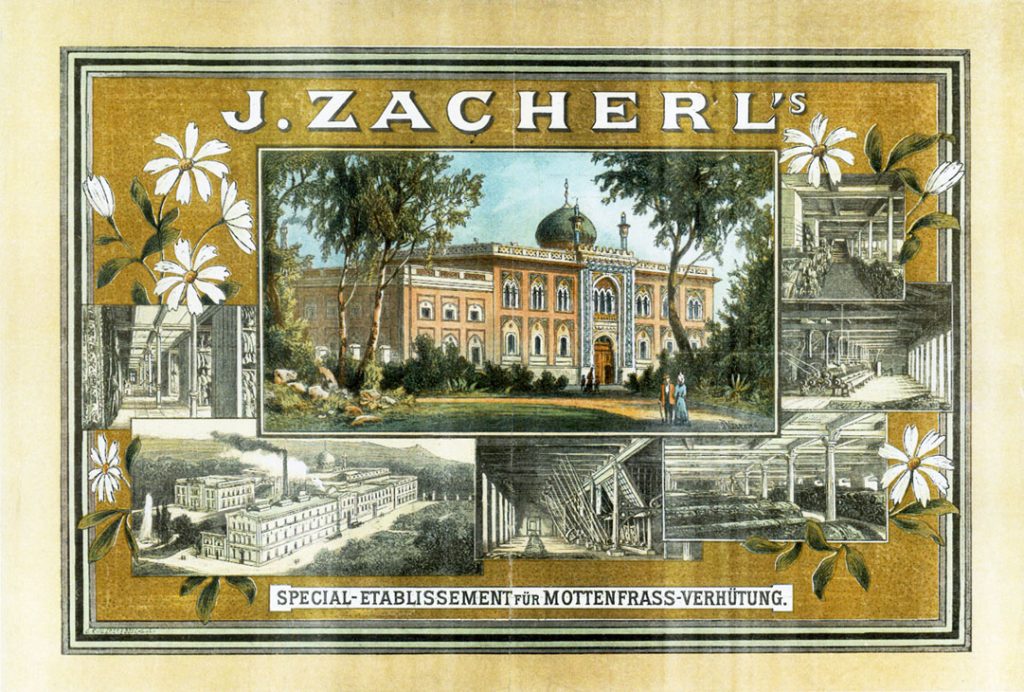

And here is where the moths enter our story. In 1814 a certain Johann Zacherl was born in Munich. Following the steps of his father he learned the pewter crafts. A few years and travels later he found employment in a pewter foundry in Vienna in 1836. He must have been an enterprising lad or a restless soul, because from there he travelled via St. Petersburg, over Moscow, Kiev, and Odessa to finally arrive in Constantinople. In the early 1840’s Zacharl moved again, this time to the Caucasus where he set up shop in Tbilisi. He had a pewter foundry, but also a wood and iron turning workshop.

In Georgie, Johann Zacherl moreover started trading tea, rum, amber, carpets and oil paintings. It is probably through his contacts with Armenian merchants in Tbilisi that he discovered ‘Persian powder’. This was in fact grounded chrysanthemum flower heads, which when mixed with water gave a powerful lotion against vermin, parasites and moths.

In the West the demand was high for an efficient protection against insects, and moths in particular: think of the damage to precious carpets, curtains and furs. Gradually Zacherl increased his trade in Persian powder (which he branded as ‘Zacherlin’). It is said that he travelled deep into the Caucasian mountains in order to organise the picking of the wild-growing chrysanthemums.

After having put in place an export network to Europe, Zacharl moved to Vienna in 1855. He first set up a shop and then a real production factory. His business expanded successfully, and later his eldest son joined the flourishing company. Today one can still admire the Oriental facade of the Viennese workplace. Part of the building is used for cultural events and exhibitions.

Johann Zacharl senior died in 1888. A bronze statue in the staircase of the former factory shows the company founder in Circassian costume. He holds a chrysanthemum in his hand.

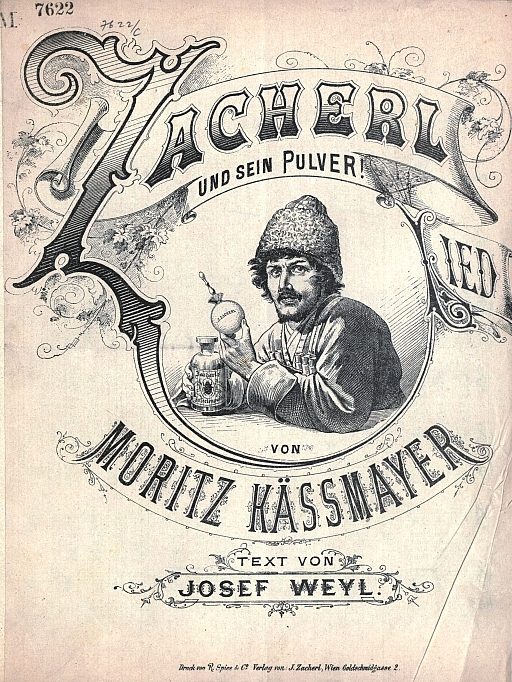

We’ve already told you that in these days they made songs about almost anything. Well…

Since I started preparing this post, and all through the writing of it, another song has persisted in my mind. It still is, and I can’t get rid of it. I know Jacques Brel’s lyrics so well.

De chrysanthèmes en chrysanthèmes

Les autres fleurs font ce qu’elles peuvent

De chrysanthèmes en chrysanthèmes

Les hommes pleurent les femmes pleuvent…

Well, it can linger in your head now, until it really gets under your skin!

Further reading on Johann Zacharl (in German): Österreichisches Biographisches Lexikon, Biographie des Monats, by Eva Offenthaler.

Met deze aflevering worden wij liefhebbers weer in de bloemetjes gezet.