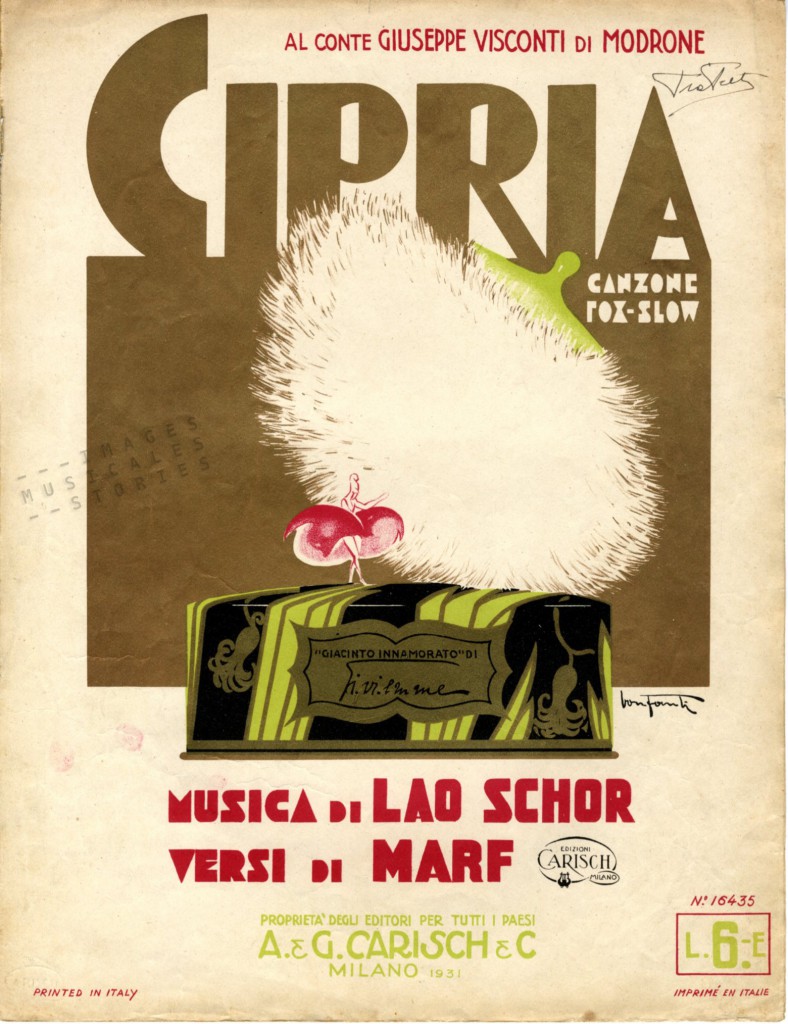

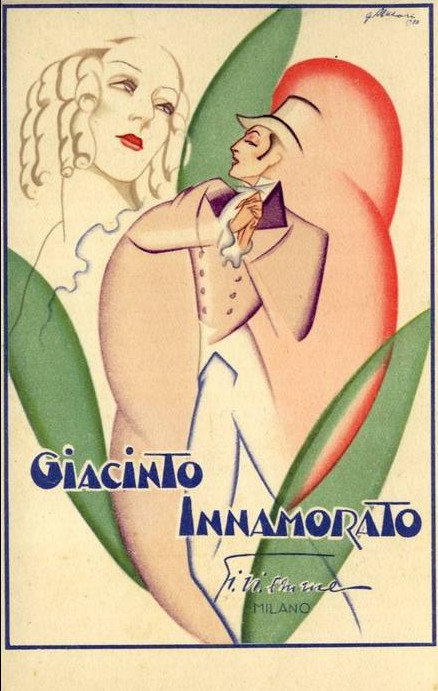

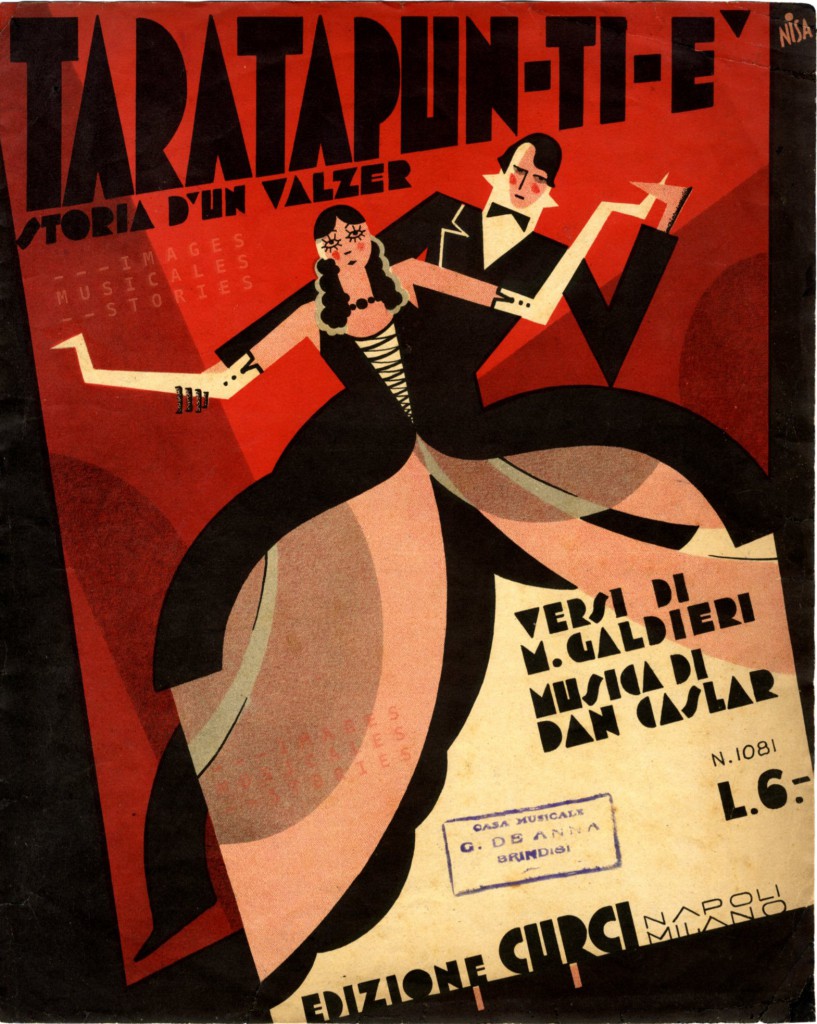

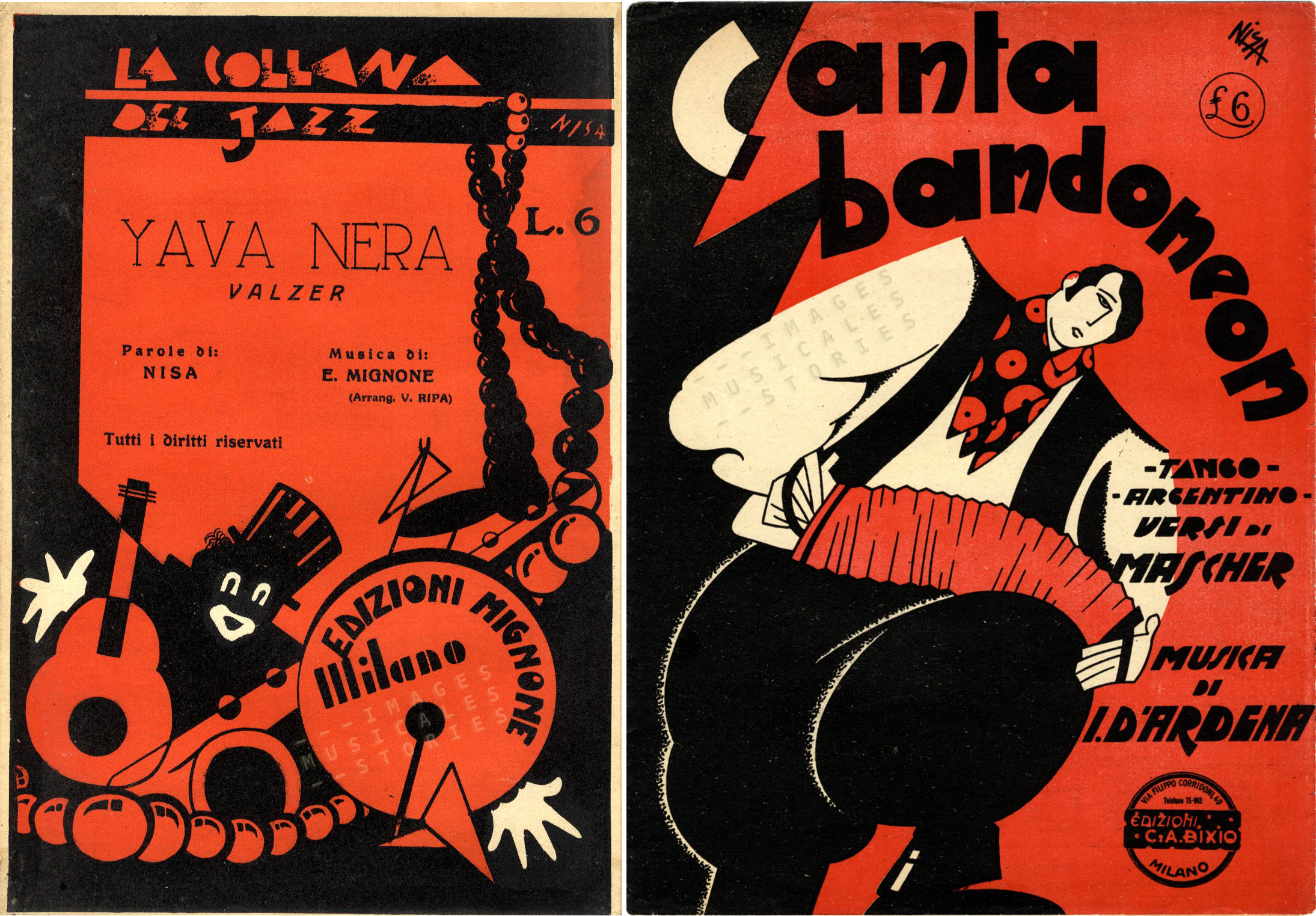

Nisa was a talented illustrator of children’s books and designer of sheet music covers (a.o. for the publishers Edizioni Curci and Bixio). Our collection holds a dozen or so Nisa covers, mostly in the typical Italian art-deco style of the Thirties.

It took us some time to discover that Nisa was a nom de plume for Nicola Salerno (1910-1969), a lyricist born in Naples. During four decades, from the Thirties until the Sixties, Nisa put his mark on Neapolitan music.

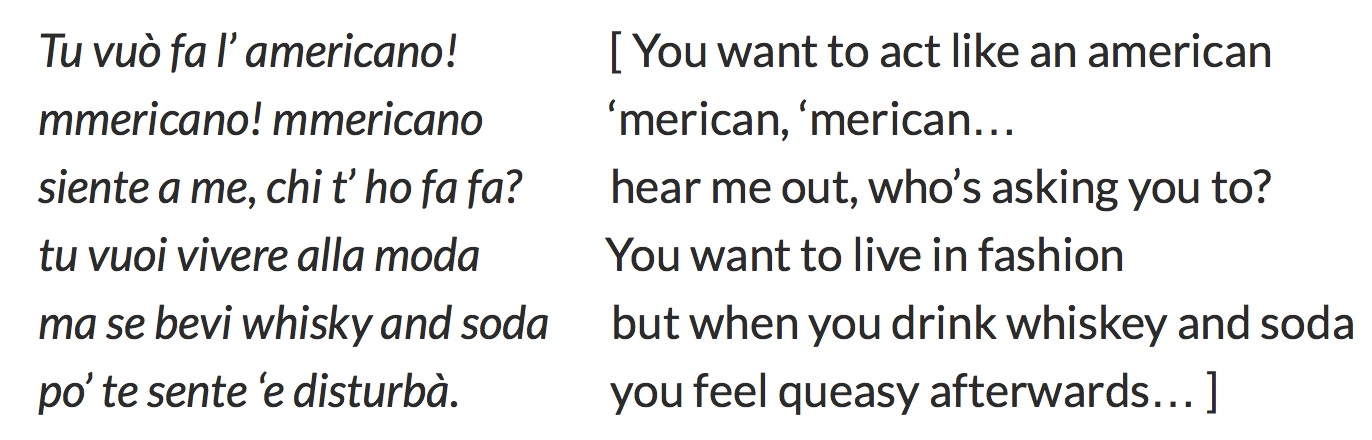

He was the writer of many songs, some of them became big hits even out of Italy. One of these songs (Tu vuò fa’ l’americano) was resampled in an Australian version and became a world-wide success in 2010. To experience once again the nervous electronic beats of ‘We No Speak Americano’, have a peek here. Or, you can enjoy the original boogie-woogie version by the cheery Renato Carosone. (Earworm alert!)

The aficionados of the Eurovision song festival will remember the 1964 winning song ‘Non ho l’età’ (previously also the winner of the Festival di Sanremo). The song is about a girl not being old enough to go out with someone for love and romance. Nisa gave words to this eternal tristesse and longing of the youth:

Non ho l’età,

[I’m not old enough]

Non ho l’età per amarti

[I’m not old enough to love you]

Non ho l’età per uscire sola con te

[I’m not old enough to go out alone with you]

E non avrei, non avrei nulla da dirti

[And I wouldn’t have, I wouldn’t have anything to say]

Perchè tu sai molte più cose di me

[Because you know many more things than me]

Lascia ch’io viva un amore romantico

[Let me live a romantic love]

Nell’attesa che venga quel giorno

[While I’m waiting for that day to come]

Ma ora no

[But not now]

…

The then 16-year-old Gigliola Cinquetti won with historic high scores. The original footage of her performance in Copenhagen was lost, but we have to thank a certain Dave (‘1947dave’s channel’ on YouTube) for editing original stills and video from her 1 minute reprise on top of the original radio broadcast. It gives a pretty good idea of the girl’s triumph in far-away Denmark…

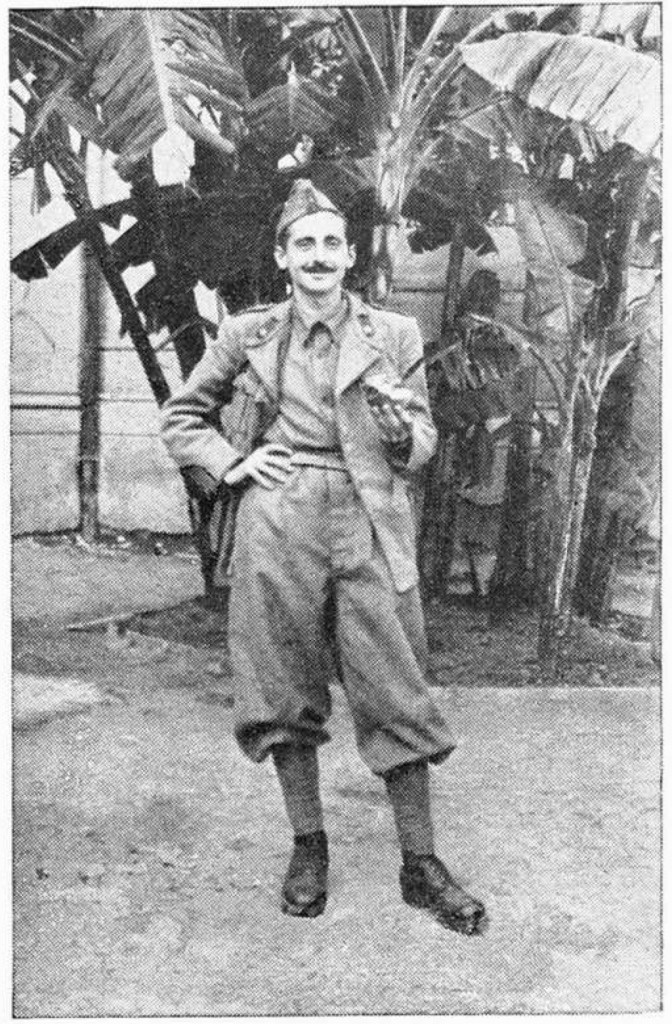

Nisa’s oeuvre of songs spans from 1937 to 1967, so tells us the Italian Wikipedia. Strangely the fascist marching song ‘L’Italia ha vinto’ (to celebrate the victory over Ethiopia in 1936) is omitted in his authorship list on l’Encyclopedia Libera.

A stain on our song writer’s reputation? Or a one-time faute de parcours? It makes us wonder how much sympathy the then 26-year old Nisa had for the fascist regime. Mussolini was then already an outspoken supporter of Franco and Hitler, and would two year later enact racist and anti-Semitic laws.

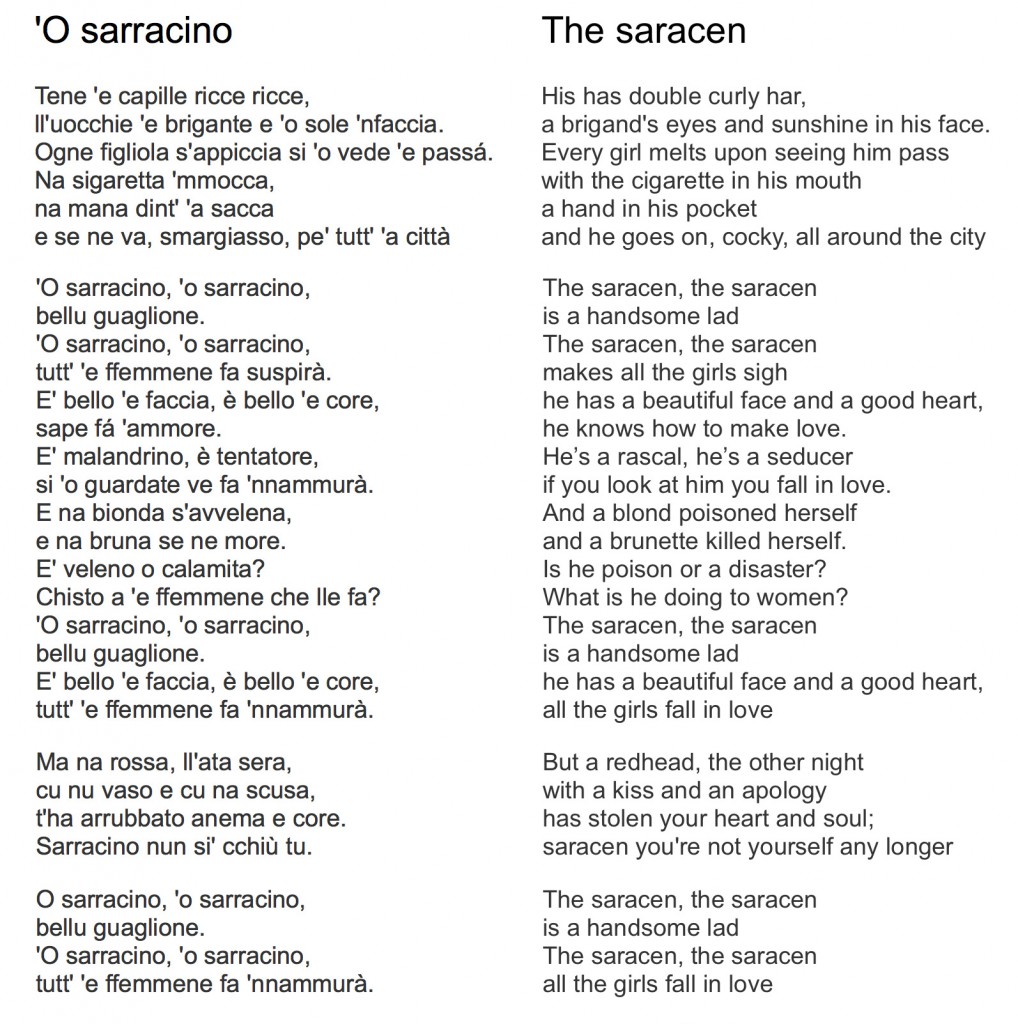

In 1958 Nisa and his composer companion Renato Carosone again scored a major hit with a song about a cool Casanova. We pluck the following lyric translation from the net:

You can find many versions of the song, but we have a soft spot for the fast pace of Rocco Granata (yes, Marina…) and Buscemi.