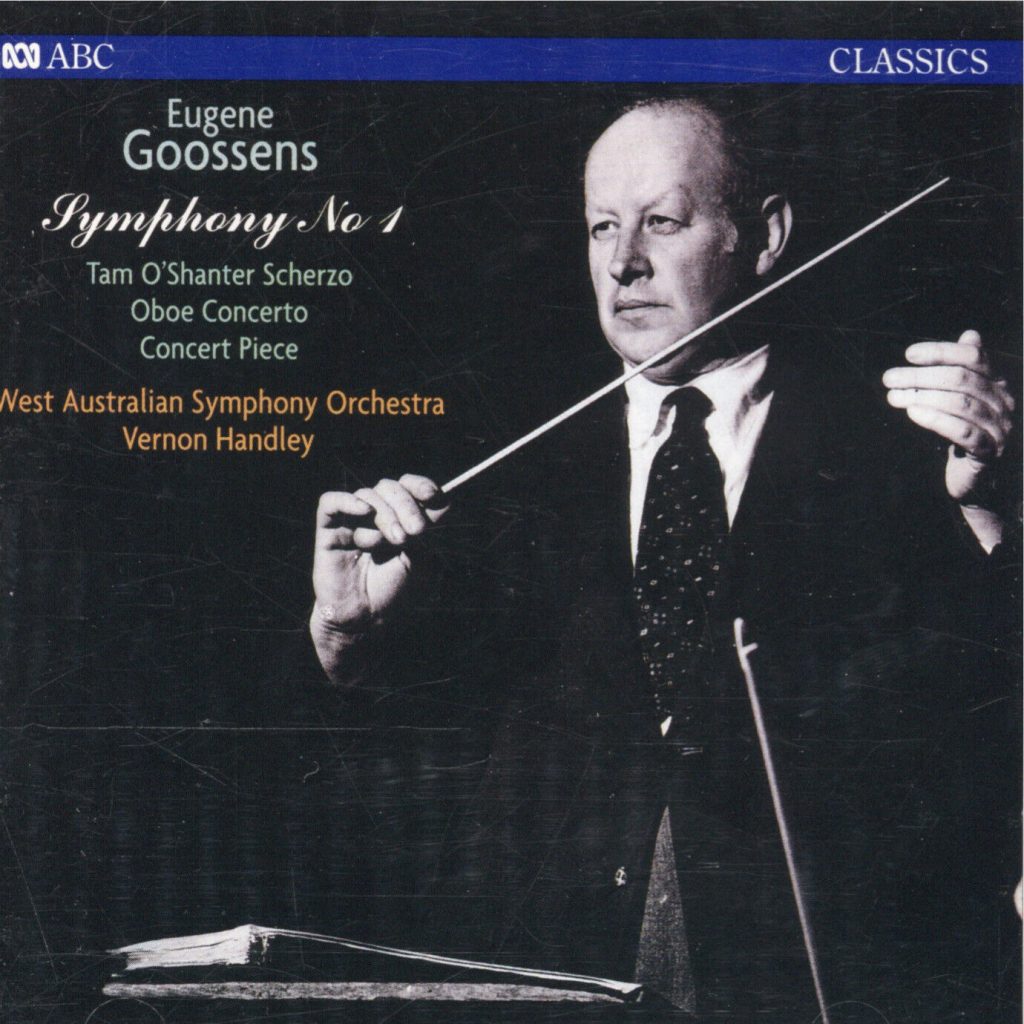

In 1893 the English composer Eugène Goossens was born into a musically gifted family. His parents and his siblings were all renown musicians. His grandfather, from Bruges in Belgium, was a famous conductor and had moved to England in 1873.

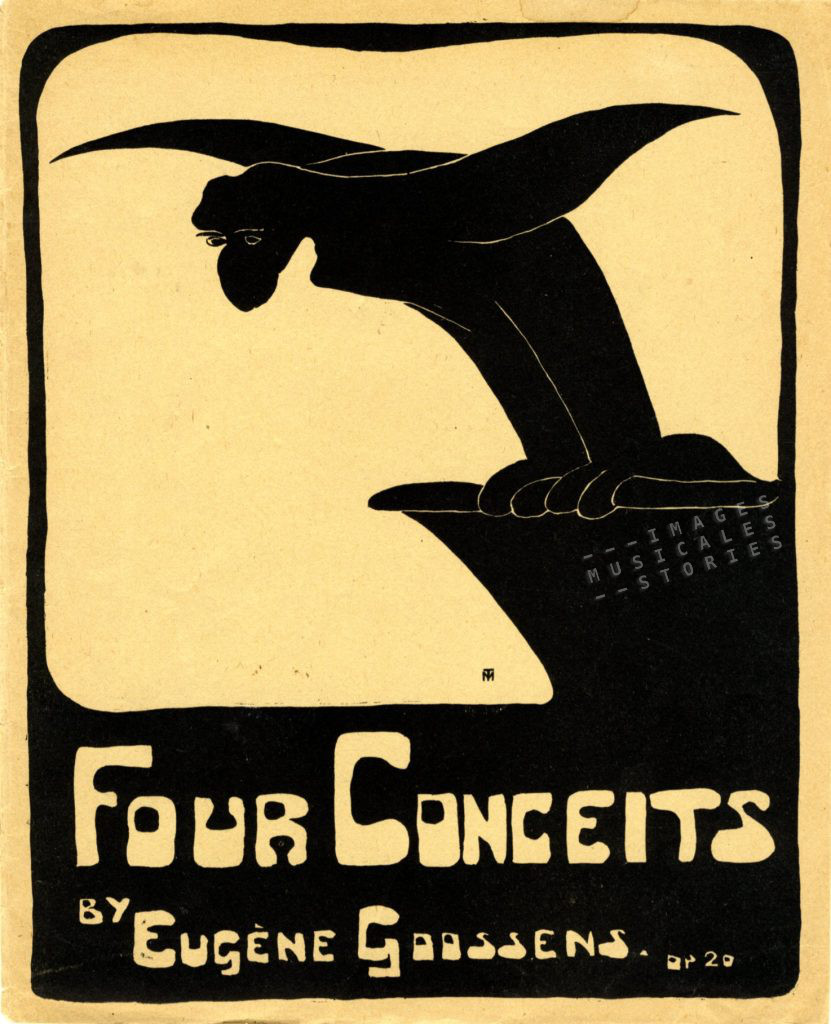

The first movement of Eugène Goossens’ Four Conceits is The Gargoyle. Eugène’s younger sister the harpist Sidonie remembers that “When he was 11 years old … he always loved to draw pictures with gargoyles. He had a sort of mania about gargoyles.” He did not draw this nice cover though, it is by M. Tempo, an illustrator we know nothing about.

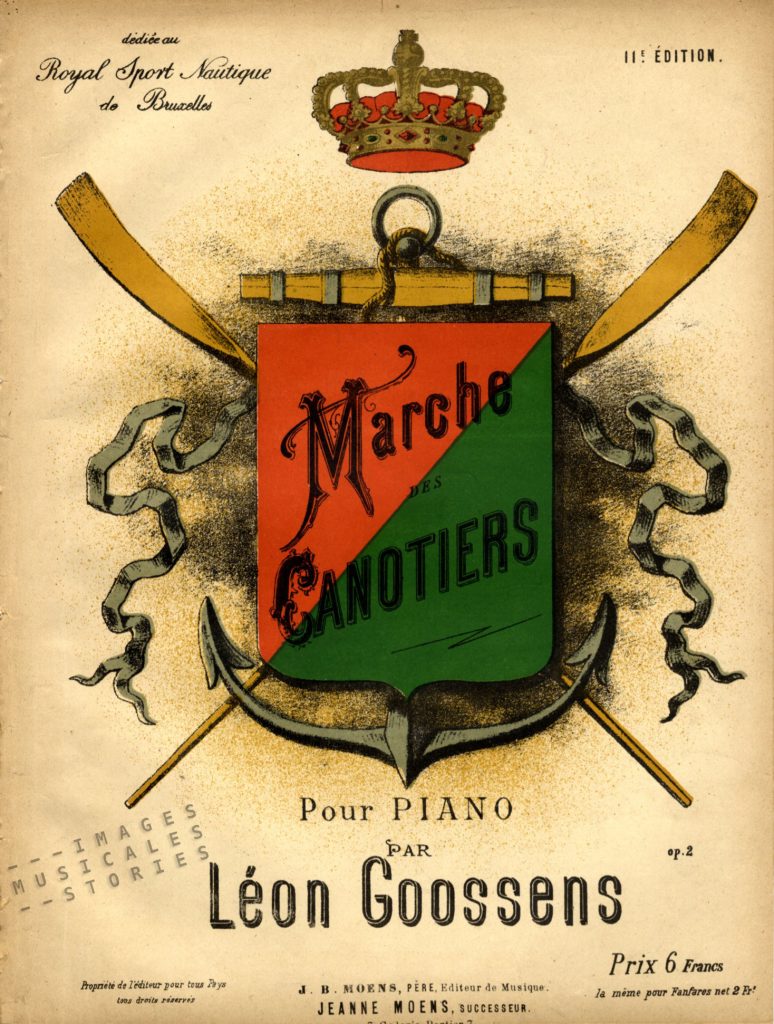

His brother Leon Goossens was considered among the premier oboists in the world and although not known as a composer he wrote a march dedicated to Brussels boaters.

After conducting US orchestras for nearly a quarter of a century, Eugène Goossens became the conductor of the Sydney Symphony in 1947. In Australia he established himself as a distinguished celebrity, earning even more than the prime minister. He also initiated the founding of the famous Sydney Opera House.

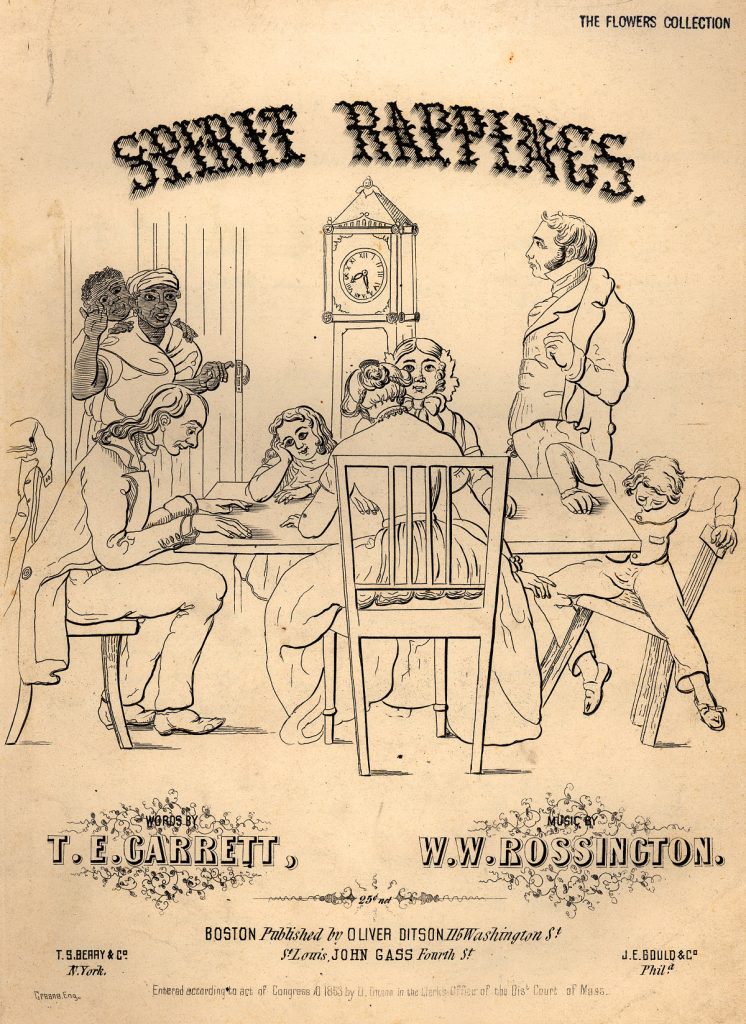

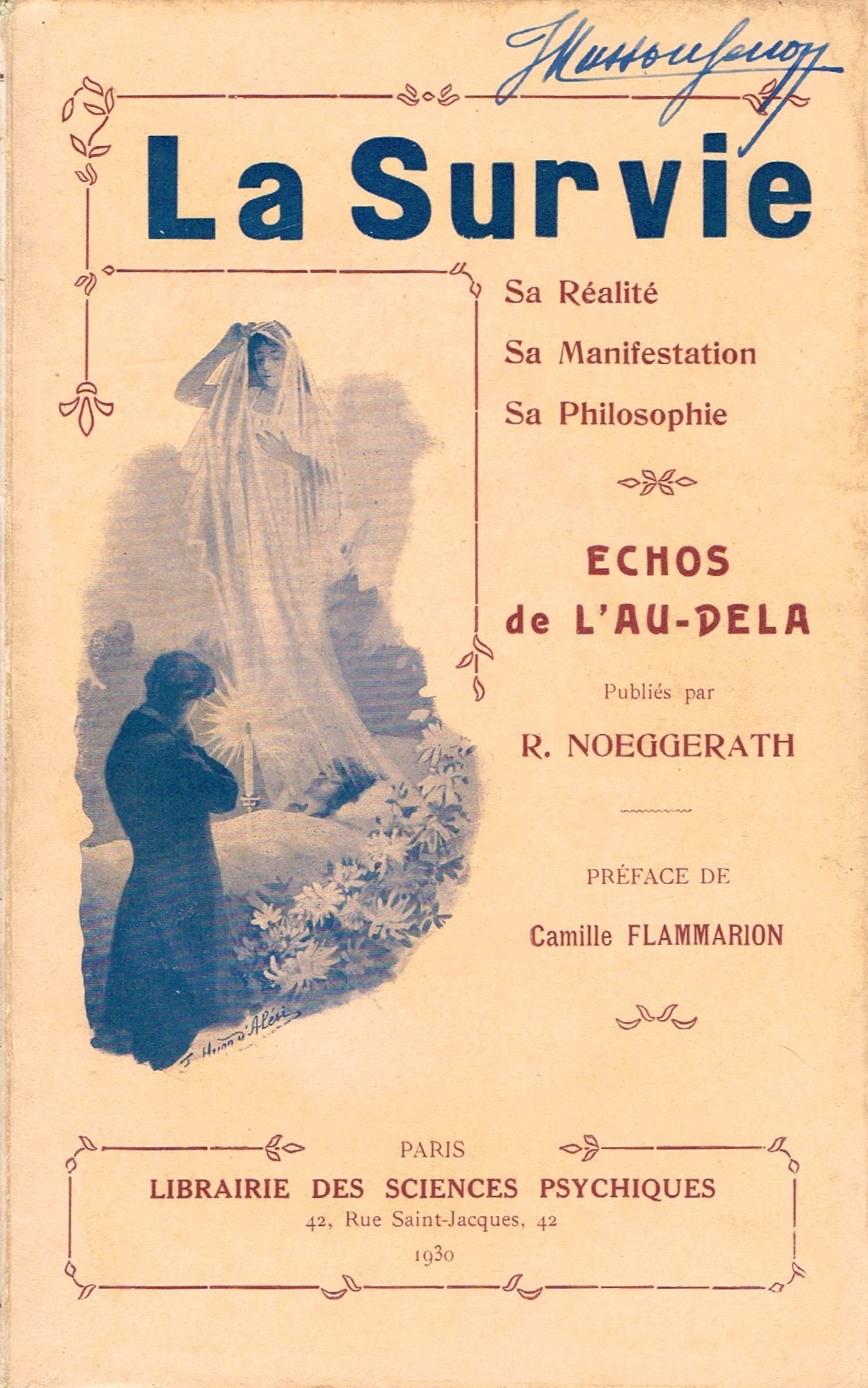

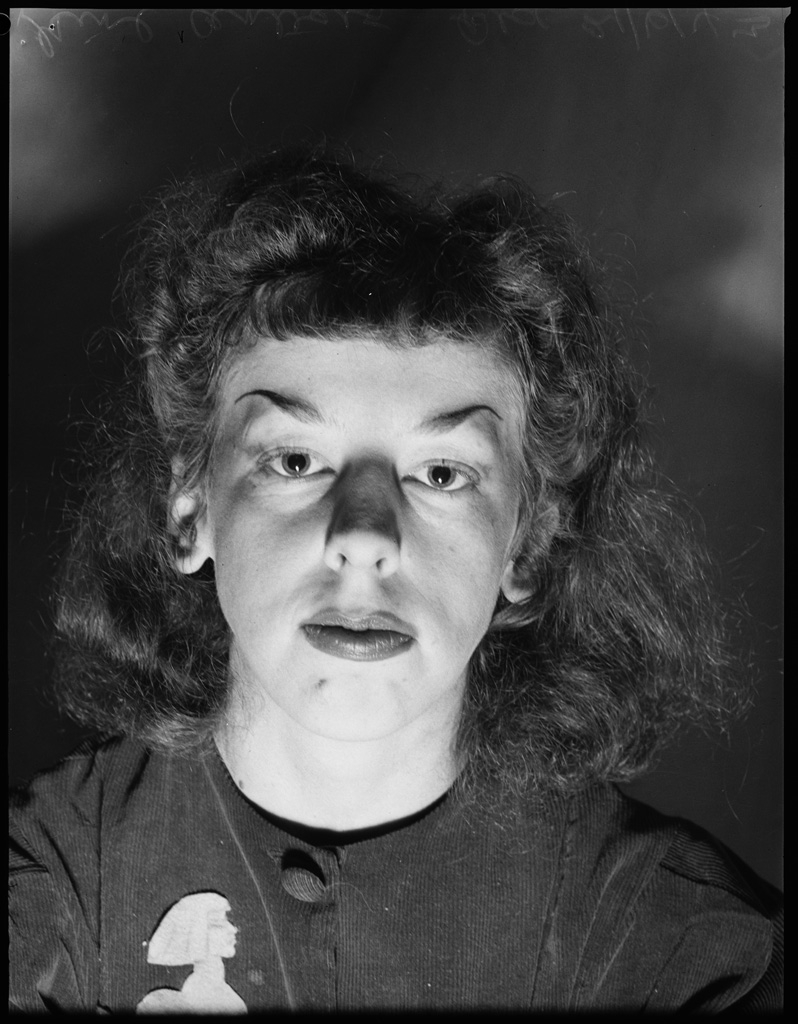

In his private live he had a lifelong interest in pantheism and the occult. Sadly this would become his downfall when in the early fifties he met the Australian artist Rosaleen Norton who had achieved scandalous notoriety as ‘the Witch of Kings Cross’. Kings Cross was Sydney’s seedy night entertainment and red-light district. There Rosaleen led a bohemian lifestyle together with her younger boyfriend, the poet Gavin Greenlees. Their small flat, in a derelict house, was decorated with occult drawings and a clumsy altar embellished with a painting of Pan and a set of stag’s antlers.

In 1952 The Art of Rosaleen Norton was published combining her (erotic) drawings of pagan gods and demons with the poetry of her lover Greenlees. The book was banned in New South Wales on the grounds of obscenity, import in the US was forbidden, and an Australian court ordered that two of the drawings had to be removed from all existing copies. This brought the book extensive media coverage. After reading it Eugène Goossens thought he had found kindred spirits and he wrote to Rosaleen. They met for tea at her sleazy flat and soon began to see each other regularly.

At that time, Eugène Goossens lived in a stylish house in Sidney with his third and much younger wife. She was a concert pianist and often away on tour, leaving Eugène —now nearing sixty— alone at home. Perhaps on the lookout for some excitement in his life, he started to take part in Rosaleen’s occult rituals. For these she was naked apart from a skimpy apron, a shawl and a mask, or she wore a robe. She and her coven members shared a ritual meal of cakes and drunk wine from a horn, which was passed round the circle.

In some private rituals Goossens, Rosaleen and Greenlees went further: they were practitioners of Aleister Crowley’s “sex magick” in the hope of reaching higher states of consciousness by performing sex rituals. Crowley —or ‘Great Beast 666‘ as he called himself— was an English occultist and ceremonial magician, and had the reputation of being the wickedest man on earth.

Eugène Goossens and the occult couple corresponded excitedly about their magical erotic experiences. The threesome was into bondage, flagellation, cunnilingus, same-gender sex and taking erotic photographs.

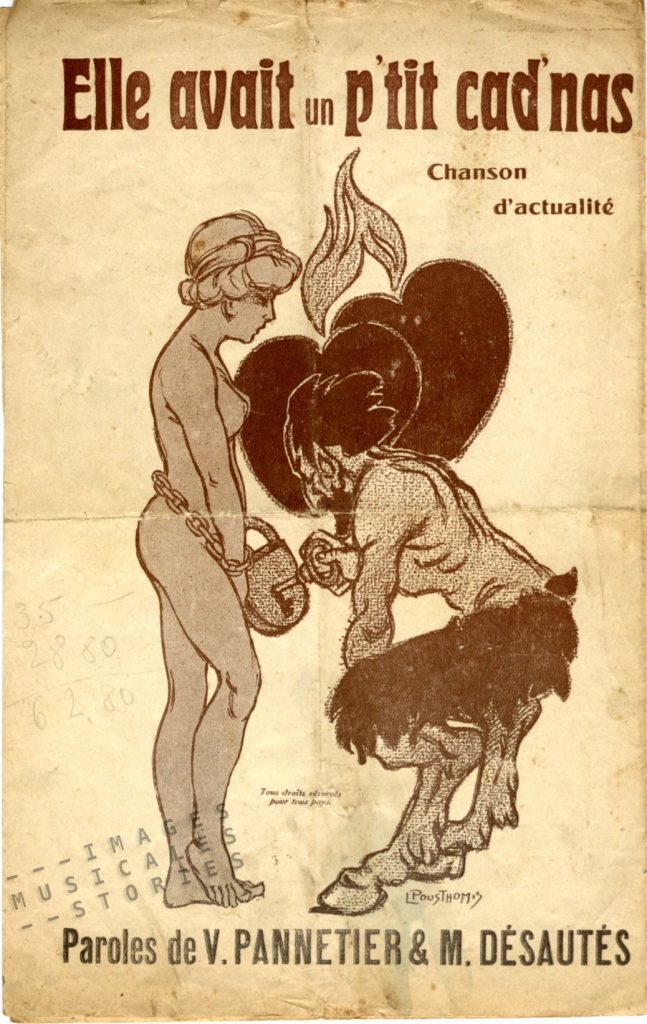

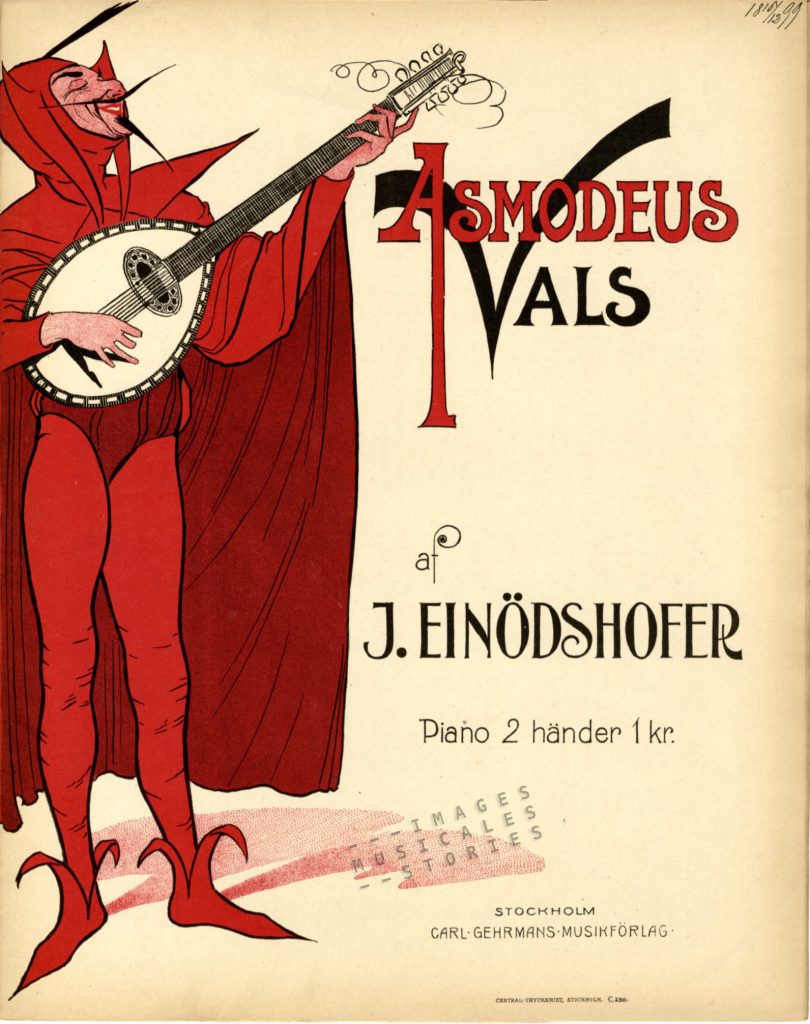

In one of his letters Goossens talked about the osculum infame that he administered to Asmodeus, the demon of lust. The osculum infame or the kiss of shame is a ritual kiss given by a witch to a devil’s behind.

Being aware that these letters were dangerous Goossens had instructed Rosaleen to destroy them. But she didn’t and hid them under a cushion of her settee. Together with bondage photographs showing Rosaleen and her lovers, the letters were stolen by a member of her coven. He tried to sell them to the tabloids whereupon a reporter of The Sun reported the theft to the police.

The police placed the unsuspecting Goossens under surveillance, even while he was abroad in England. When Goossens returned to Australia in March 1956, he was detained at the airport. Customs officials already knew they would find a large amount of ‘pornographic’ material which included 800 erotic photographs, books and rubber masks. Humiliated and in shock, Goossens instantly and naively pleaded guilty thus jeopardising his legal defence. A major scandal broke loose in puritanical and narrow-minded Australia of the fifties. The story was fodder for the tabloids. In disgrace, Eugène Goossens returned to Britain — his international career was ruined.

Please allow me to introduce myself…