Tutankhamen, aka Tutankhamun, was a pharaoh of minor historical importance. He reigned more than 3.000 years ago for fewer than ten years and died at a young age. Yet he is somewhat the celebrity of Ancient Egypt. That is largely because, when his tomb was found in 1922, it was almost intact: it still contained the magnificent treasures intended to accompany the boy-king into the afterlife. The antechambers were packed to the ceiling with more than 5.000 objects. And Tutankhamen’s portrait mask, made of solid gold laid with precious stones, is one of the most beautiful archaeological objects of Ancient Egypt.

It was the British archaeologist Howard Carter, backed by his patron Lord Carnarvon, who discovered the tomb. He had searched the Valley of the Kings for Tutankhamen’s resting place for many years. To examine and clear the tomb it would take him and his team eight more years. The phenomenal discovery of the tomb and all these wonderful things, in Howard Carter’s own words, kicked off a worldwide ‘King Tut’ craze or Tut-mania in the 1920s that would continue well into the Thirties.

Every stage of the excavations was chronicled by the press. To finance the dig, Lord Carnarvon had sold the exclusive rights to the Times for the then huge sum of £5.000. It gave the Times unique access to the tomb and the opportunity to publicise its fabulous contents. To compete with the Times’ success, other media created wilder stories, some of which were based on exaggerated claims and even falsehoods, rather than on actual events. So did Lord Carnarvon’s sudden death, within weeks of the tomb’s opening, lead to speculations of a curse.

Expert photographer Harry Burton, documented the eight-year-long uncovering of King Tutankhamen’s tomb. For that purpose Burton learned to operate a movie camera. With it he recorded the opening of Tutankhamen’s sarcophagus. His creative and technically advanced images and films contributed largely to the Tut-mania phenomenon.

Apart from being celebrated by the media, Tutankhamen also notably influenced the arts and culture in the 1920s. Egyptian motifs became an integral part of Art Deco. They decorated fabrics, jewellery, furniture, ceramics, and were ornamental in architecture. Even in society Egyptian hairstyles and costumes became fashionable.

As a result of this Tut-mania, Egypt blossomed as a tourist destination for rich people. Travels to it though, were time-consuming. Tourists could —as did the Belgian queen Elisabeth— travel first by train to Italy, and then board a passenger steamship in Genoa. After a stopover in Naples they would arrive in Alexandria or Port Said four days later.

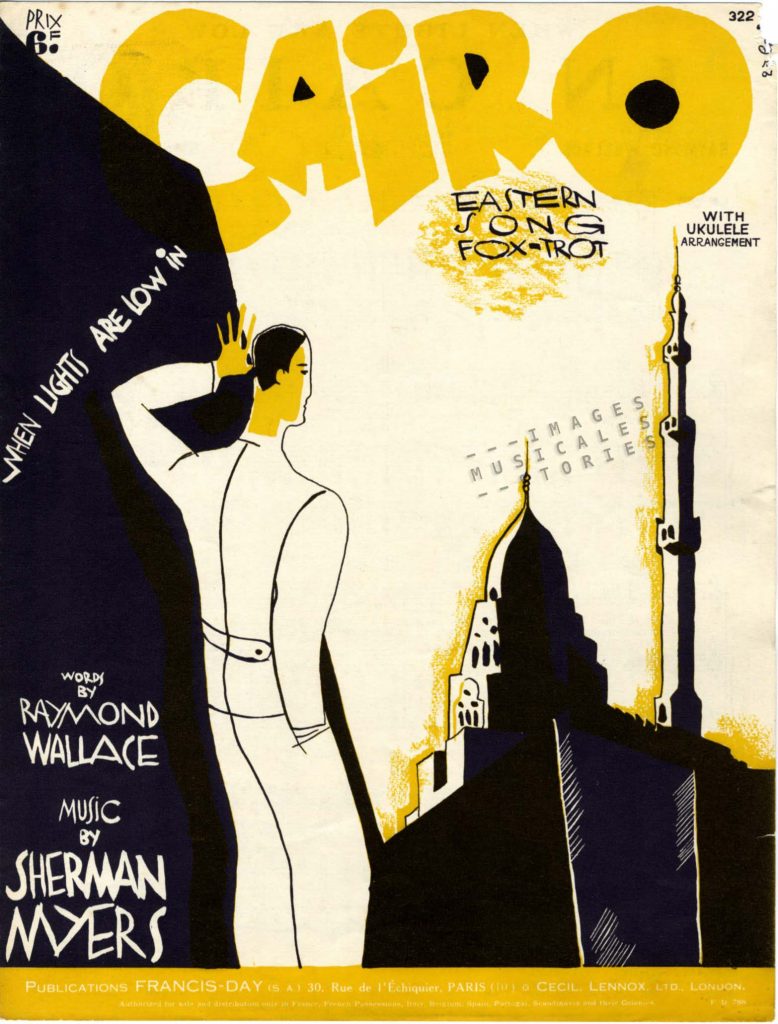

Each Egyptian adventure started in Cairo where one could swarm the bazaars and curio shops.

From there one visited the obligatory sphinx and took a sightseeing camel ride around the pyramids.

Then one took a wagon-lit to Luxor, or visited the famous ruins along the Nile by steamer.

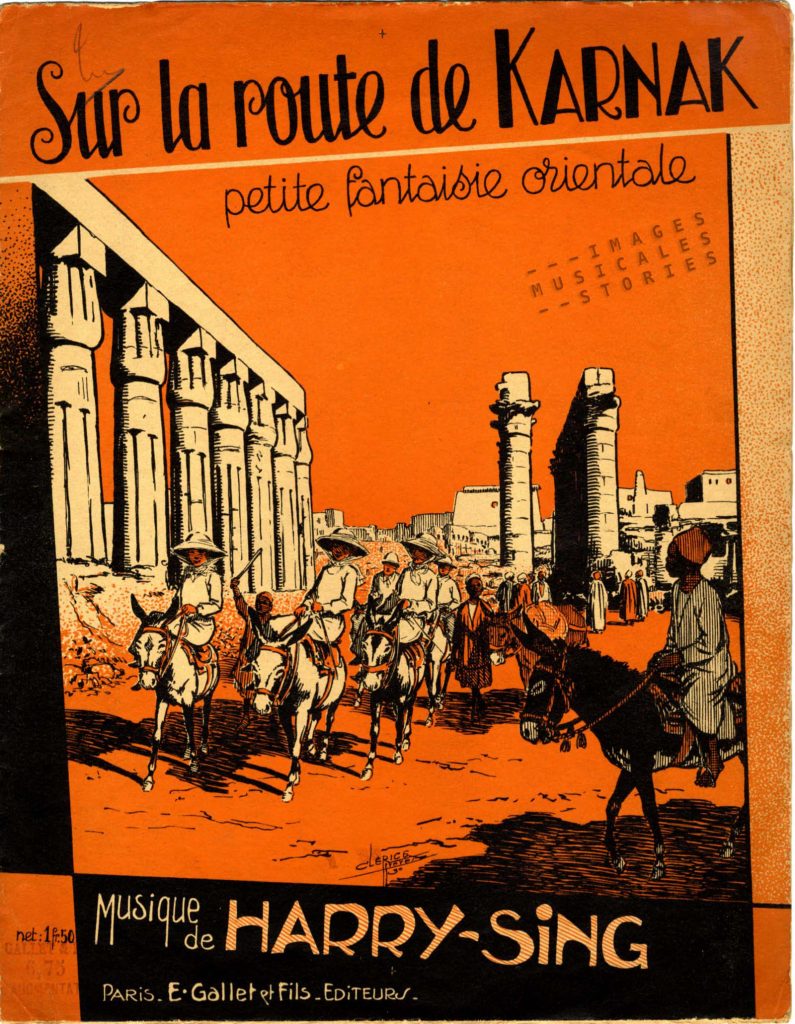

In Luxor one checked in at the Winter Palace Hotel or one of the other luxury hotels. With a bumpy ride on a mule under the scorching sun one went to see the Karnak temple complex…

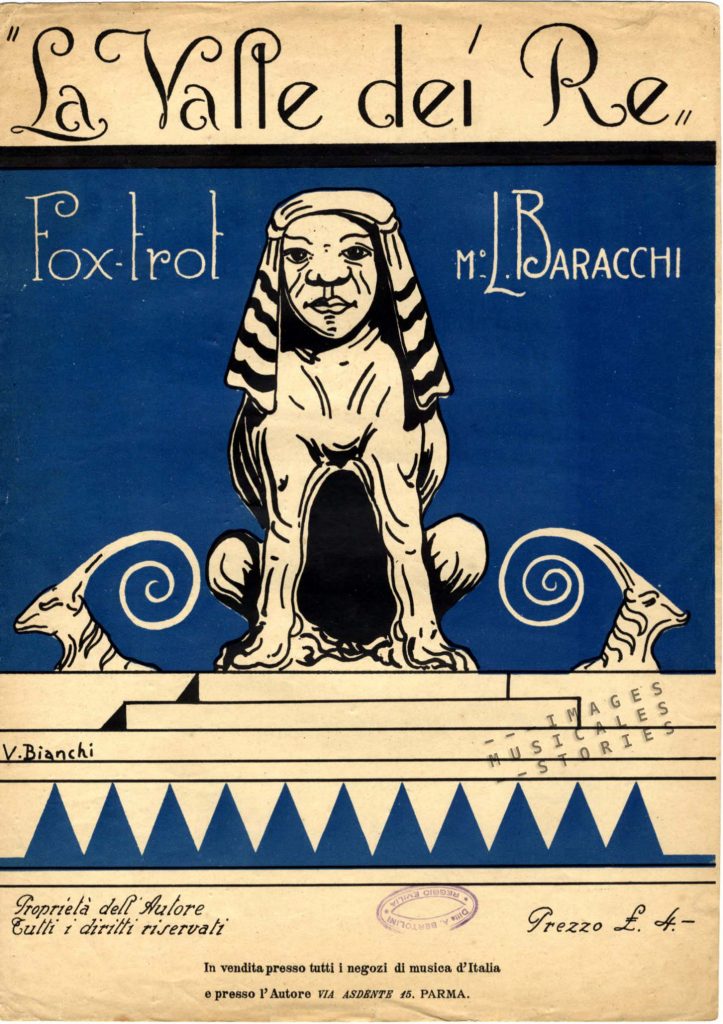

… to finally arrive at the high point: the Valley of the Kings and the grave of Tutankhamen.

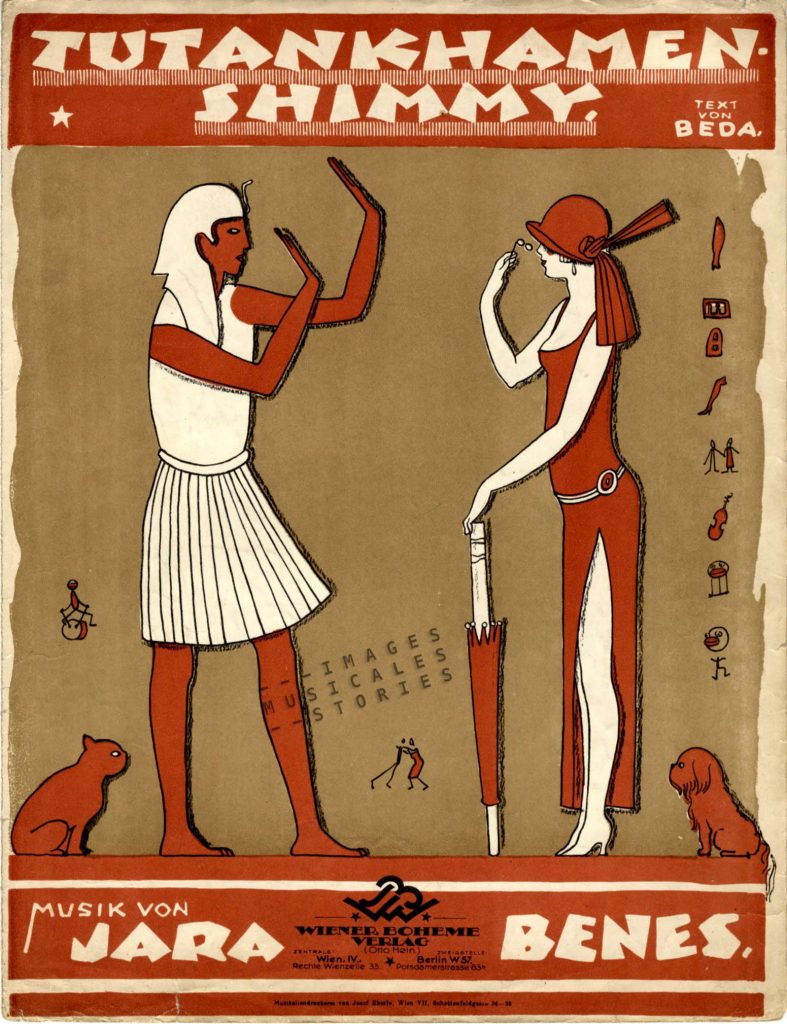

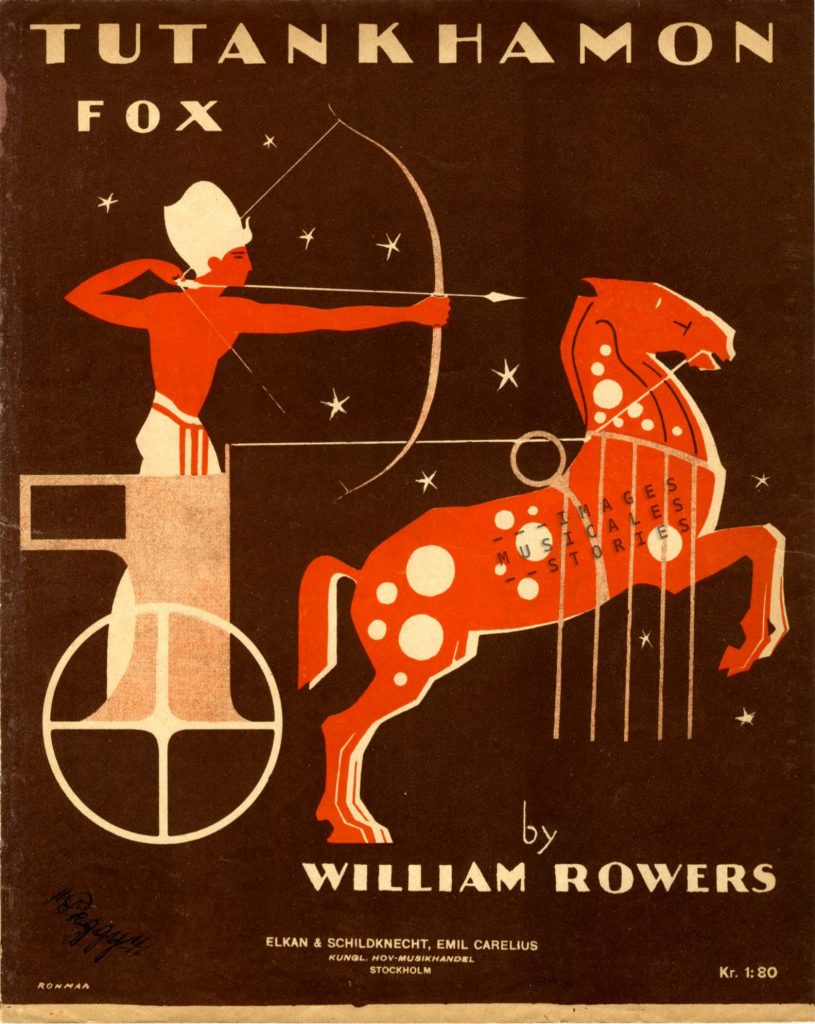

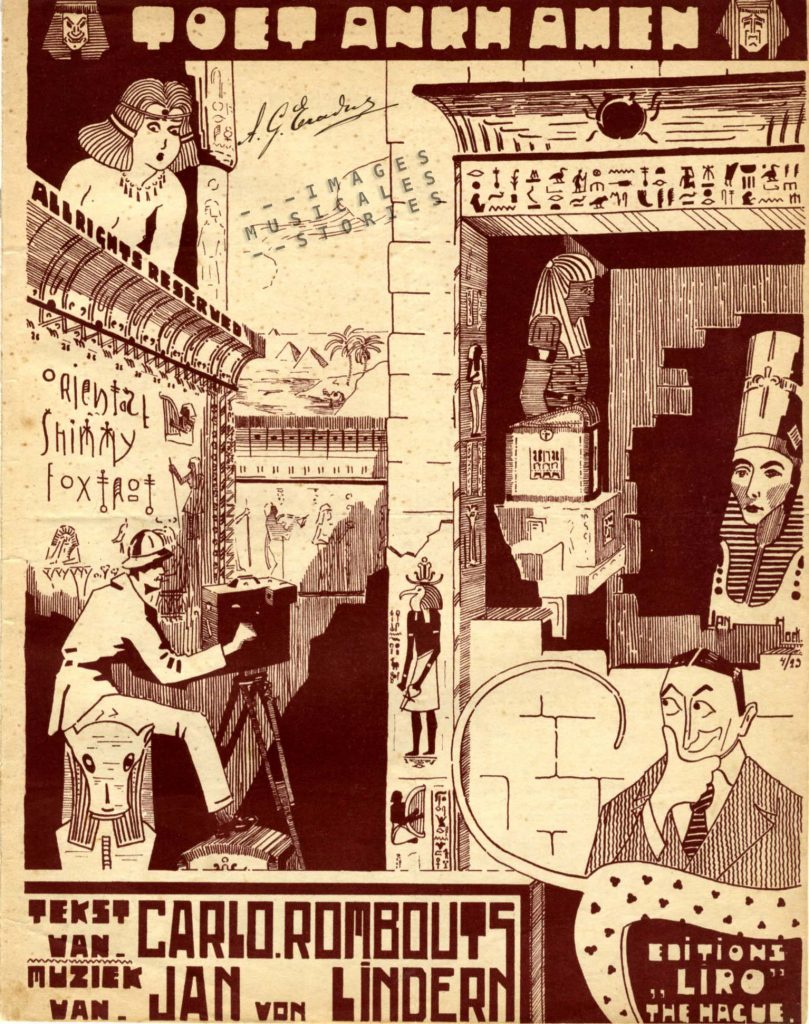

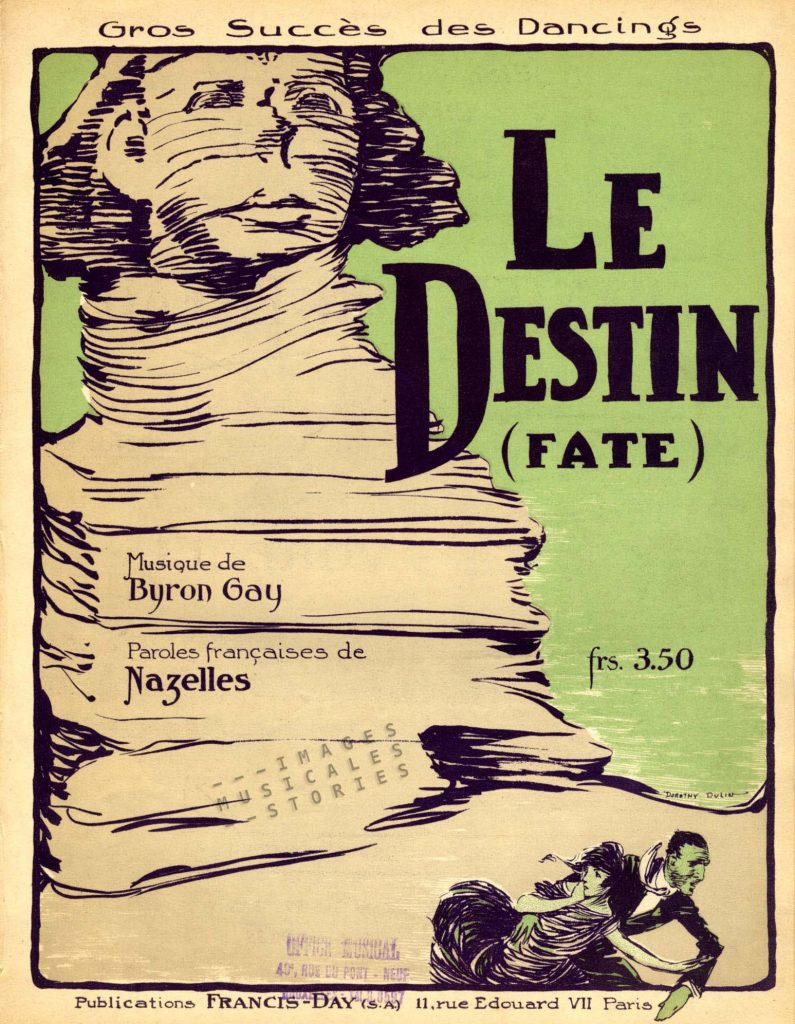

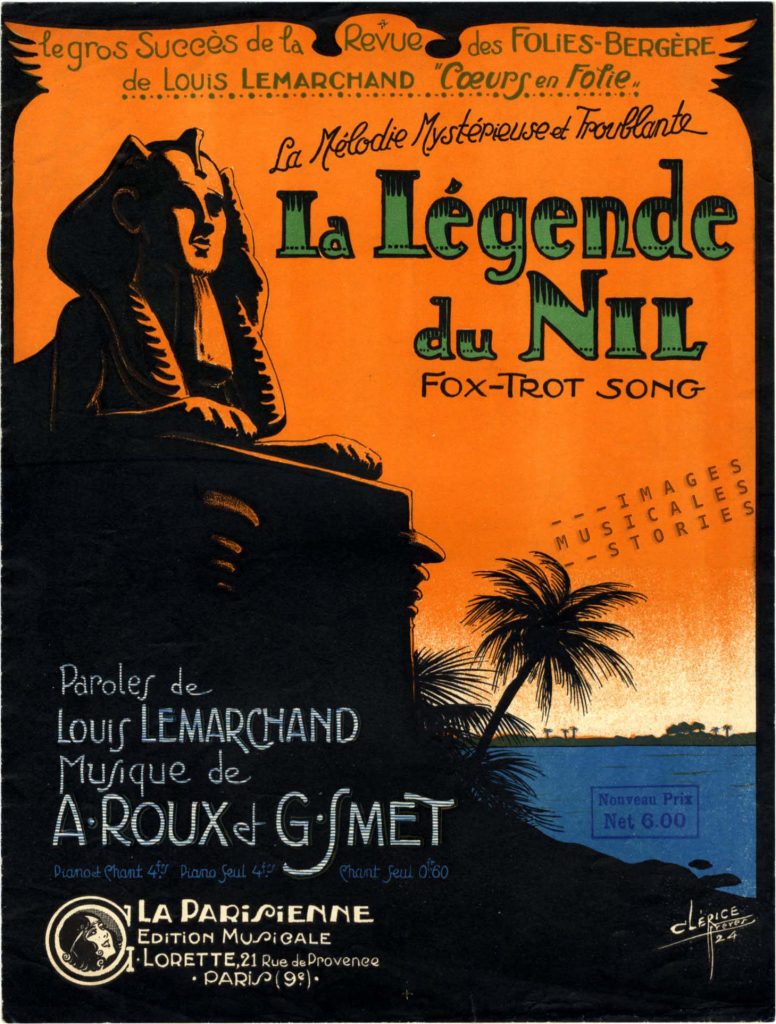

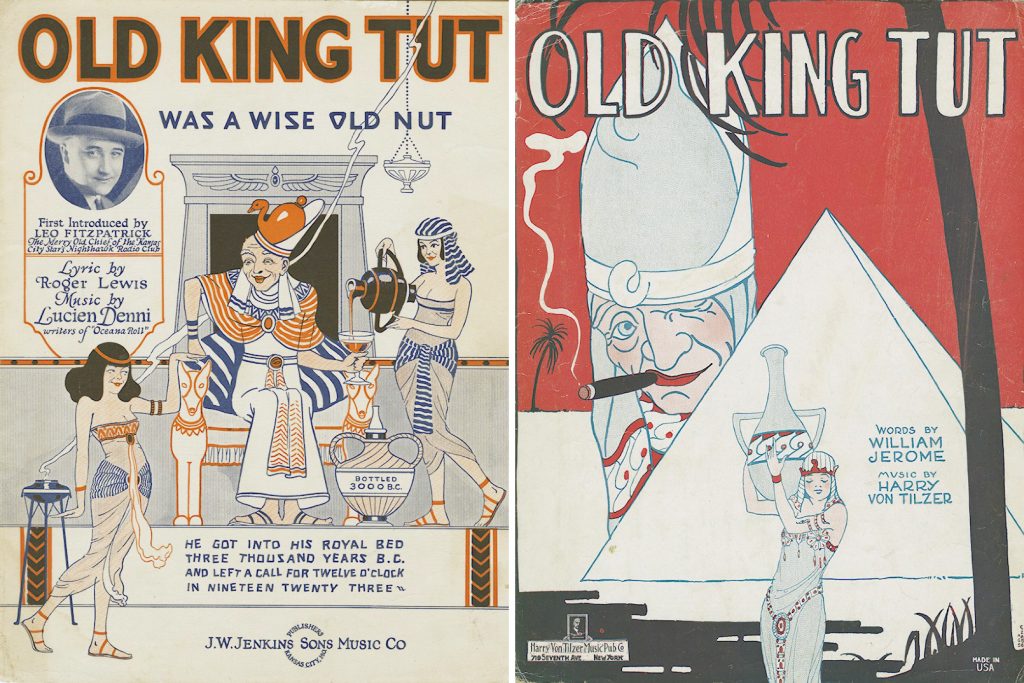

And of course Tut-mania made its mark on the music world also. Soon after King Tut’s discovery, his effigy started to appear on sheet music covers.

One of the most popular songs was Old King Tut by Harry von Tilzer and William Jerome (1923). Another one (Old King Tut was a Wise Old Nut) was published around the same time. Both depict Tutankhamen as an old man. No one knew at the time that when ‘Old King Tut’ died he was in fact a very young man.

Recently, the song by Harry von Tilzer has featured in the television show ‘Boardwalk Empire’:

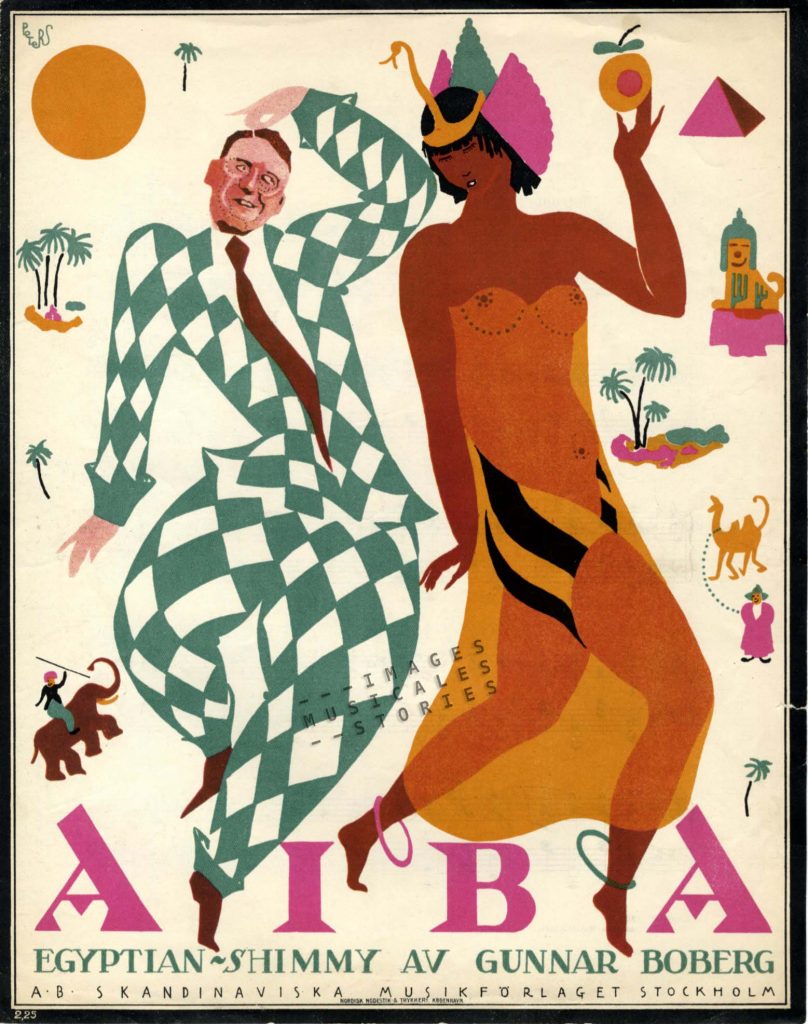

The Tut-mania craze gave rise to a number of novelty dances, with poses one can see in the Ancient Egyptian reliefs. Not easy to twist your limbs this way. Known for his quirky illustrations, Peter Curt shows us the popular Swedish composer Gunnar Boberg trying out the ‘Egyptian walk’.

The British vaudeville artists Jack Wilson and Joe Keppel show you how it is done. Easy enough, get Alexandre Luigini’s Ballet Egyptien on Spotify, throw some sand on the floor and start shuffling!

Even though my grandfather, Wolfgang Ortmann, is not responsible for Tutankhamen Shimmy, I love it, and I have it framed on my office wall.