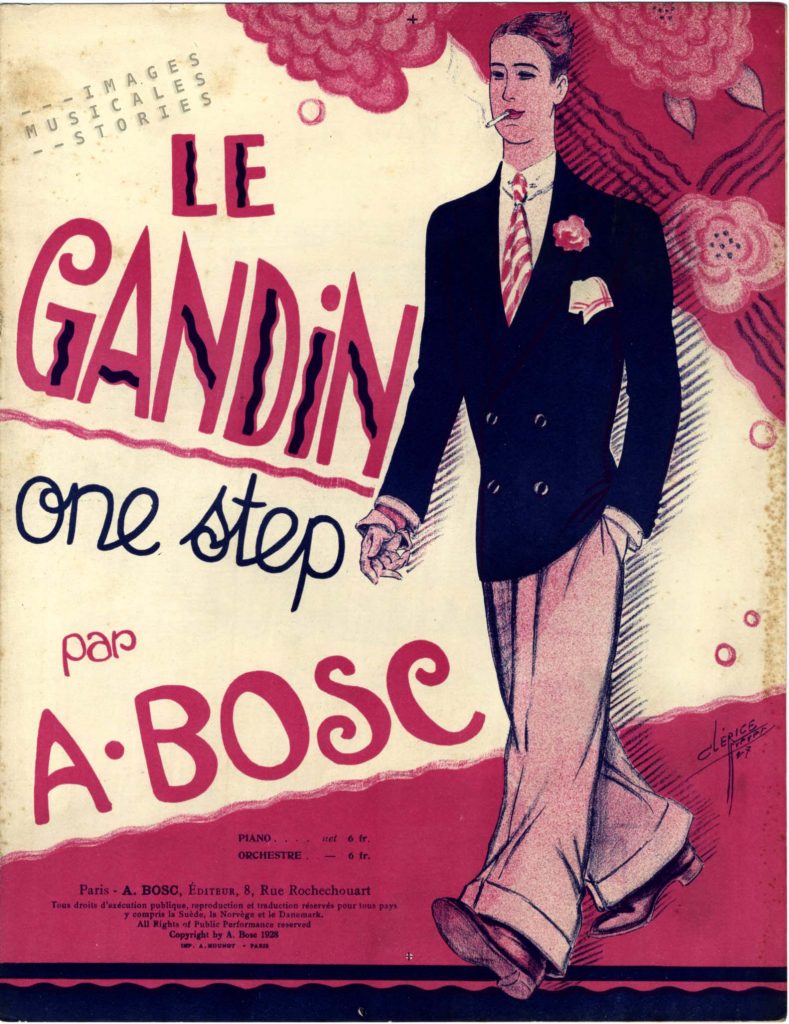

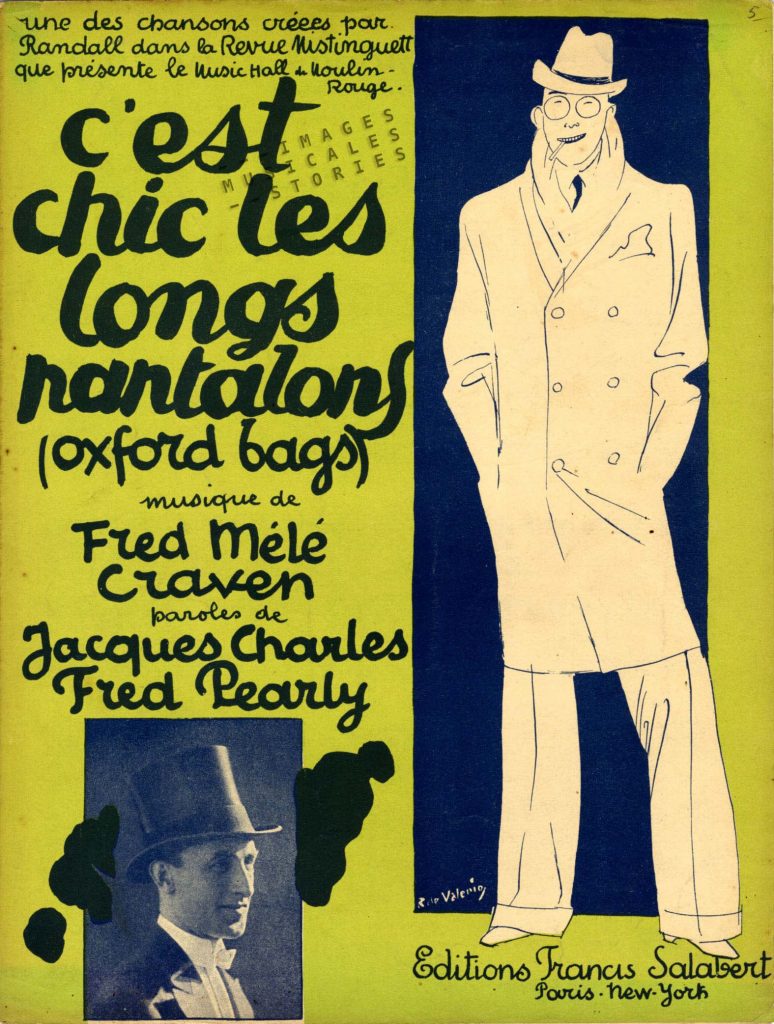

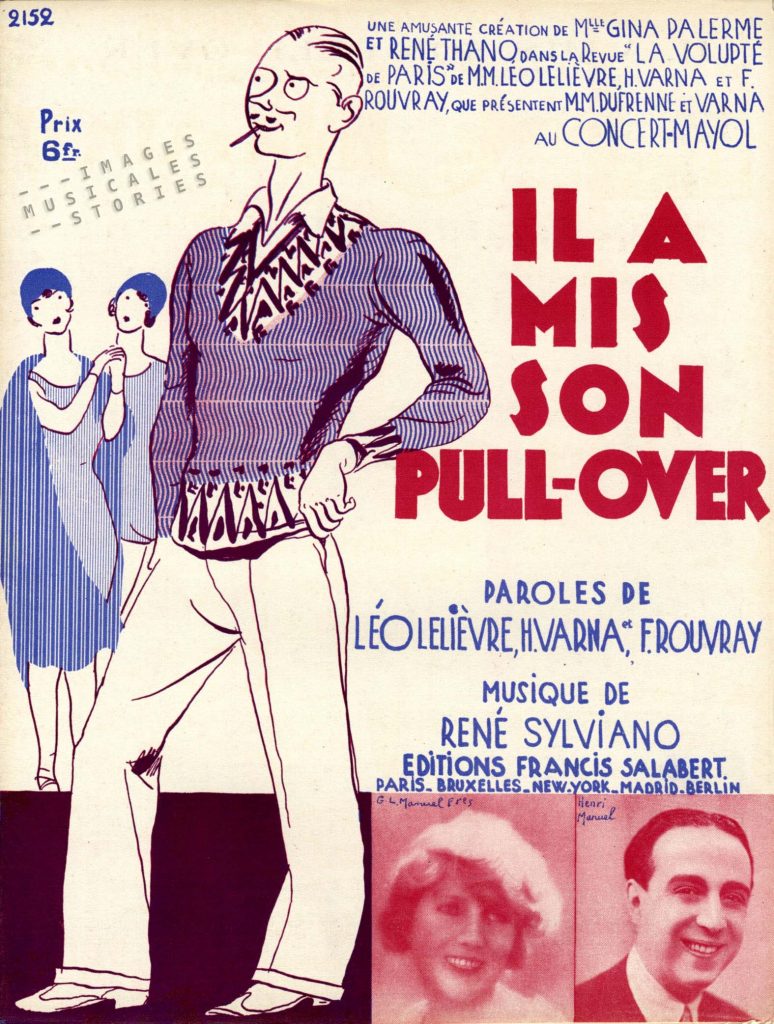

Bloomers were not the only pants fashion worthy of a song or dance. Proudly this young man struts around, wearing very capacious trousers called Oxford bags. The fashion of these wide-cut trousers started in 1924 in the city of youth, Oxford. They were typically made of flannel, with a circumference of usually 66 cm around the knee and 60 cm around the ankle. These Oxford bags were sometimes also named ‘Charleston trousers’ or ‘collegiate pants’.

In those days young men in Oxford were seen as fashion icons. They were reported in the newspapers and their vestimentary code had a worldwide impact. Our sheet music covers are sure witnesses of that influence on the vogue in Paris.

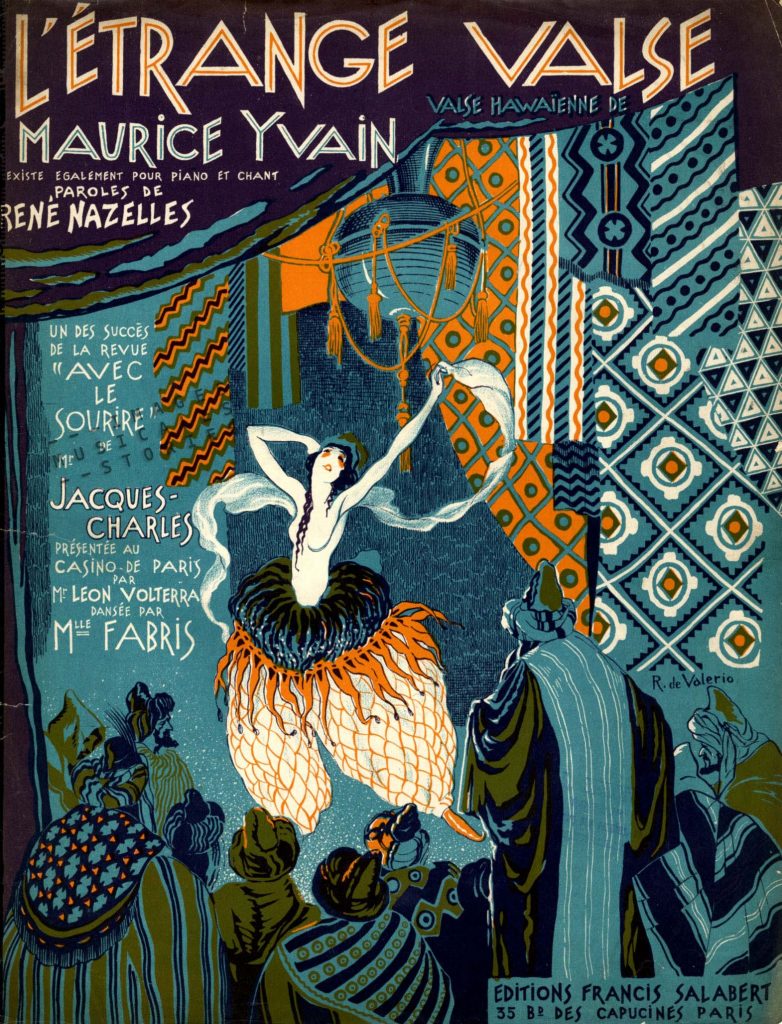

The instant popularity of the Oxford-style trousers is illustrated by the song C’est chic les longs pantalons or Oxford Bags created at the Moulin Rouge in 1925. The cover for this song is illustrated by Roger de Valerio. He might have drawn a self portrait here: the young man is wearing de Valerio’s typical round horn-rimmed spectacles. Or he could have been joking: allegedly some followers of fashion wore these round spectacles with plain glass just to give “an appearance of owlish sapience”.

French papers were making fun of the ‘elephant leg’ trousers. Surely, if fashion wasn’t French it could not be elegant, could it?

It is said that these large trousers became the style because students were not allowed to wear knickerbockers in lectures, so they hid them under Oxford bags. However, the belief is now that rowers used to slip them over their shorts during cold weather, the equivalent of a tracksuit. One such a pair of rowing-over trousers (already coined Oxford bags in 1896) is kept at the River & Rowing Museum, in Henley-on-Thames.

At first Oxford bags were worn with a double-breasted blazer but soon they were accompanied by pullover sweaters, another Oxonian fashion statement. “Conservative Oxford continues to add bizarre notes to the prevailing mode of men’s fashion. After the flapping Oxford bags of a previous year fanciful coat-sweaters of exotic colours, called pullovers have captured the undergraduate fancy.” (The Chicago Tribune, 26 October 1926). The newspaper continued to state that the pullover’s unusual popularity may be traced to the 1926 lockout of one million coal miners and the ensuing cold lecture rooms.

The Oxford trousers as a fashion item were taken to extremes. One pair even had a 122 cm wide hem, and extravagant trousers such as these were getting all the attention. But still, the normal kind of Oxford pants were to stay right up into the 1950s.

In the 1970s Oxford bags found their second life in the Northern soul scene, a British subculture that emerged out of the mod movement in the North of England. The youths danced all night to rare vintage vinyls of black American soul with a heavy beat and fast tempo. They had a particular dance style, spinning around, kicking in the air, performing splits and backdrops. A typical sweat-soaked all-nighter was fuelled by popping Dexedrine pills to keep dancing for hours. Beer was not served though, because the dance clubs could stay open as long as no alcohol was offered.

For practical reasons the boys chose light and loose-fitting clothes to easily move in: high-waisted Oxford bags, polo shirts, sports or track jackets and leather soled shoes for good gliding across the dance floor. Often patches representing the soul club allegiance were sown on the vest or shirt.

In this 25 minutes ‘Wigan Casino’ documentary from the seventies we can appreciate the dance moves of Northern soul devotees who lose themselves to their favourite music. The Wigan Casino (1973-1981), a night club in Greater Manchester, was the primary venue for Northern soul music.