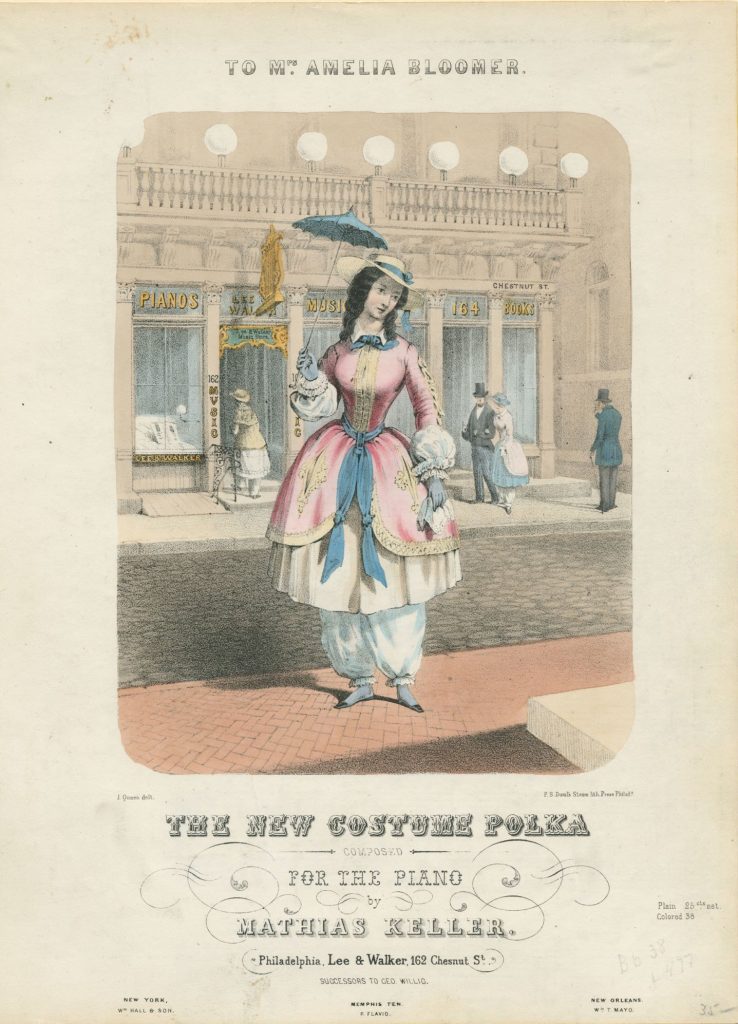

On the cover of The New Costume Polka an elegant woman holds a tiny blue parasol. She wears a corseted coat and wide skirt over her white bloomers. The outfit is trimmed with elegant golden galloons and decorated with blue ribbons. We see other women dressed in bloomer costume on the sidewalk and entering the shop (which is a detailed depiction of the music publisher’s store, see the street address and the model harp above the entrance). The sheet music is dedicated to Mrs. Amelia Bloomer.

Bloomers first appeared in the 1850s as an alternative to the heavy dresses. They were loose-fitting ankle-lenght trousers, inspired by Turkish pantaloons and worn under a shorter skirt. The garment was named after Amelia Bloomer, an American women’s rights and temperance activist. Amelia Bloomer did not invent the bloomers though, it was another women’s rights advocate, Elizabeth Smith Miller who first wore the outfit. But Amelia Bloomer enthusiastically promoted wearing pantaloons in The Lily, the first American newspaper edited by and for women.

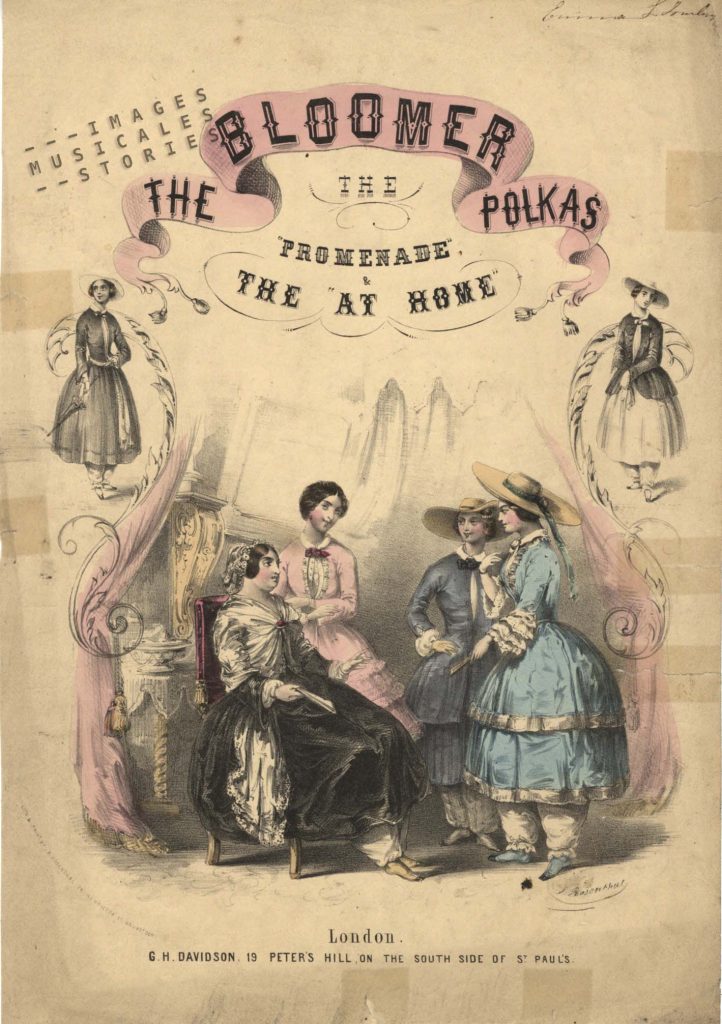

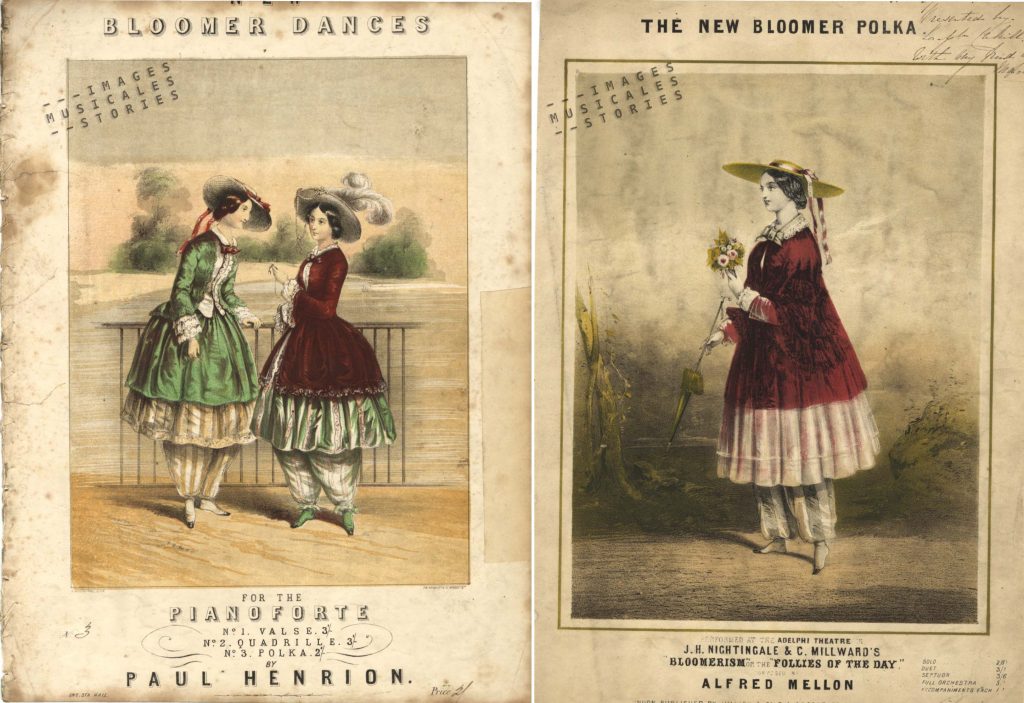

As most leaders of the women’s rights movement and emancipated women wore the new costume, bloomerism became synonym for an early form of feminism. The bloomers were fiercely mocked by opponents and an avalanche of cartoons and satirical poems followed, criticising those who wore them. The New Bloomer Polka was performed in the London sketch ‘Bloomerism or The Follies of the Day‘.

And so, although Amelia Bloomer dressed for several years in bloomers, in 1859 she dropped the fashion in favour of conventional ankle-length dresses. She gathered that the attention and the ridicule in the popular press became a distraction: “We all felt that the dress was drawing attention from what we thought of far greater importance—the question of woman’s right to better education, to a wider field of employment, to better remuneration for her labour, and to the ballot for the protection of her rights.”

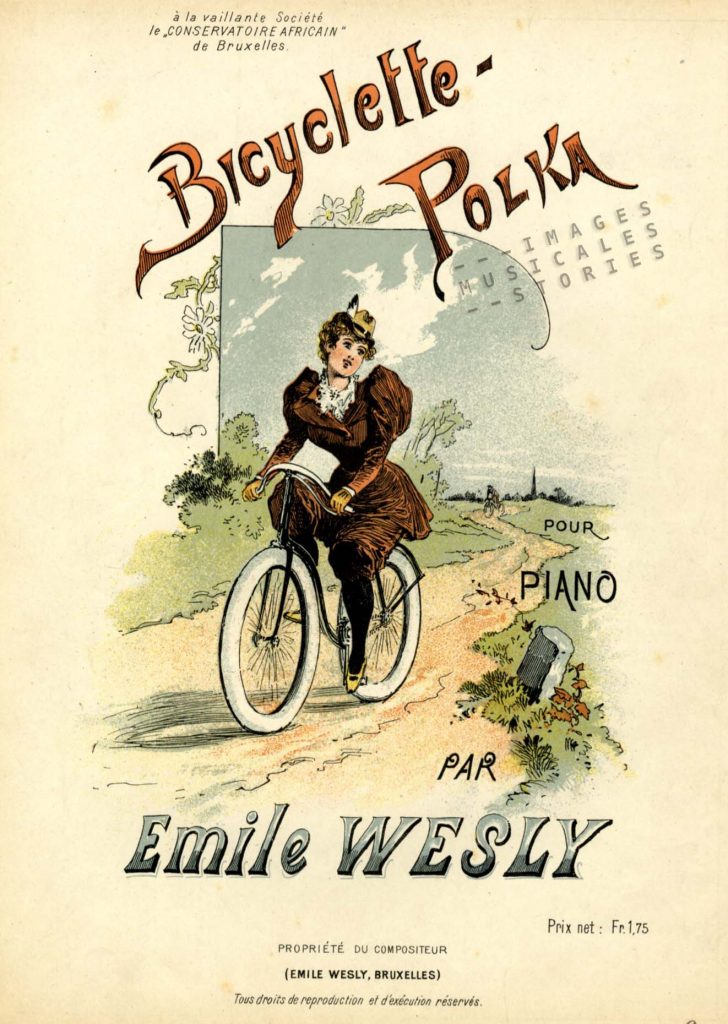

The bloomer costume died—temporarily. It was to return much later (in a different form), as a women’s athletic costume in the 1890s and early 1900s. It goes without saying that these cycling trousers, along with women on bikes, were also a target of ridicule.

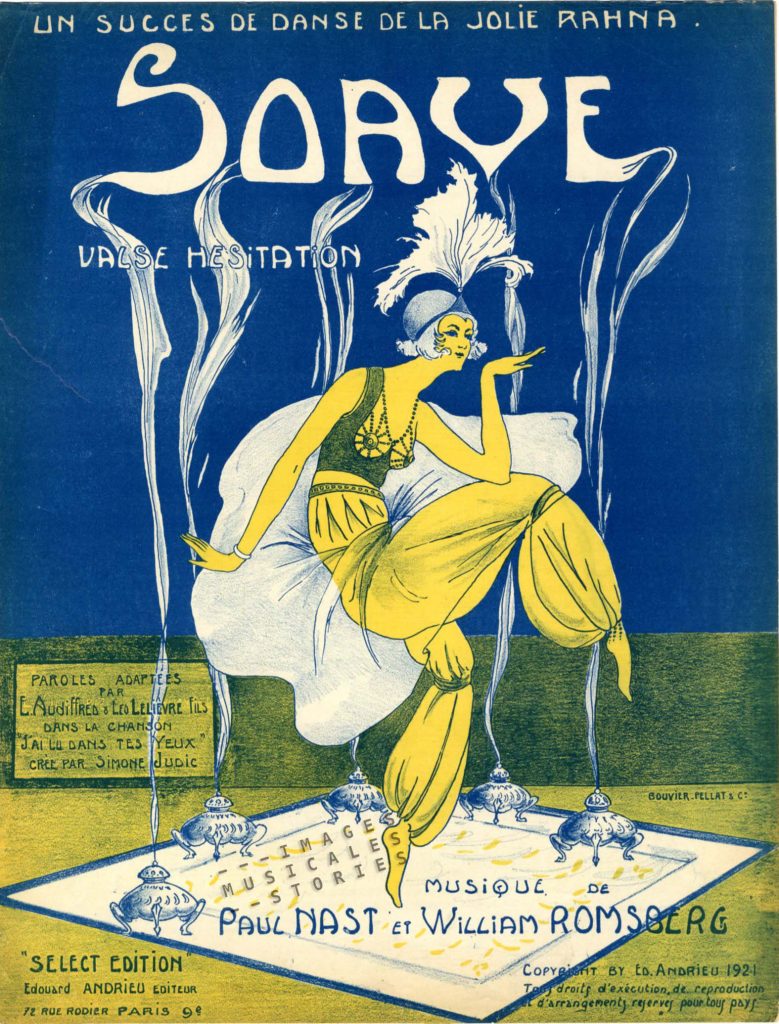

But that wasn’t the swansong of the baggy garnment: the loose-fitting trousers surfaced again in 1911 when couturier Paul Poiret launched his Orientalistic collection and the Style Sultan. Remember that Parisians were at that time enchanted with eastern exoticism and easily dazed by Arabic-Islamic fragrance. From then on the harem trousers, as they became known in the fashion world, would follow the whimsical waves of what is in vogue, and sometimes even be seen as an anti-fashion statement…

What Amelia Bloomer and her feminist companions wouldn’t have dared to imagine is that the bloomers or harem pants would, certainly in the Twenties at the height of art deco, become a symbolic attire —admittedly with at least a hint of nudity— to represent women in their most servile condition: that of the harem woman, with no other role than to please men’s sexual fantasies.

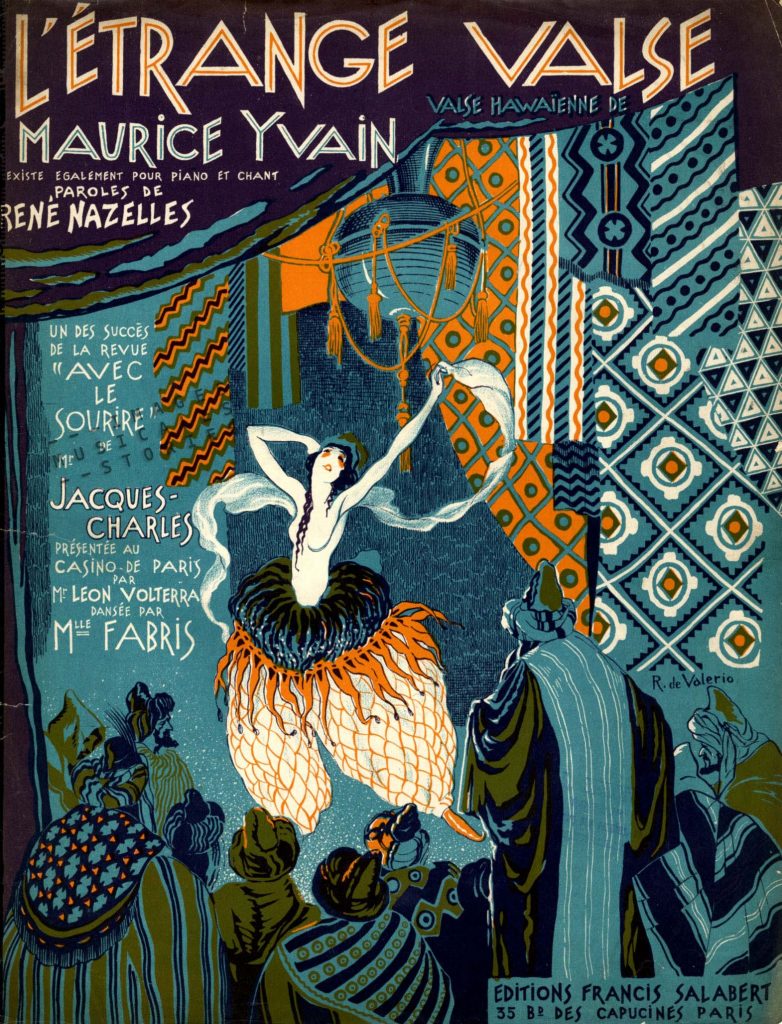

Hey, what a perfect excuse to show some interesting sheet music covers in our collection. They use all the stereotypical elements of such imagery, including a languid female, the implicit eroticism, and an ethnographical backdrop.

And even in the Sixties orientalism had not lost any of its British mystique… You’ll have to imagine your own entrancing rhytm to this silent Pathé film.

Wonderful! tanks! It looks like a dance contest, with a jury.

How History can be funny: there are now in several towns lessons of belly dancing, especially in Stockholm (with probably some feminist connotation)! Around Paris, too….