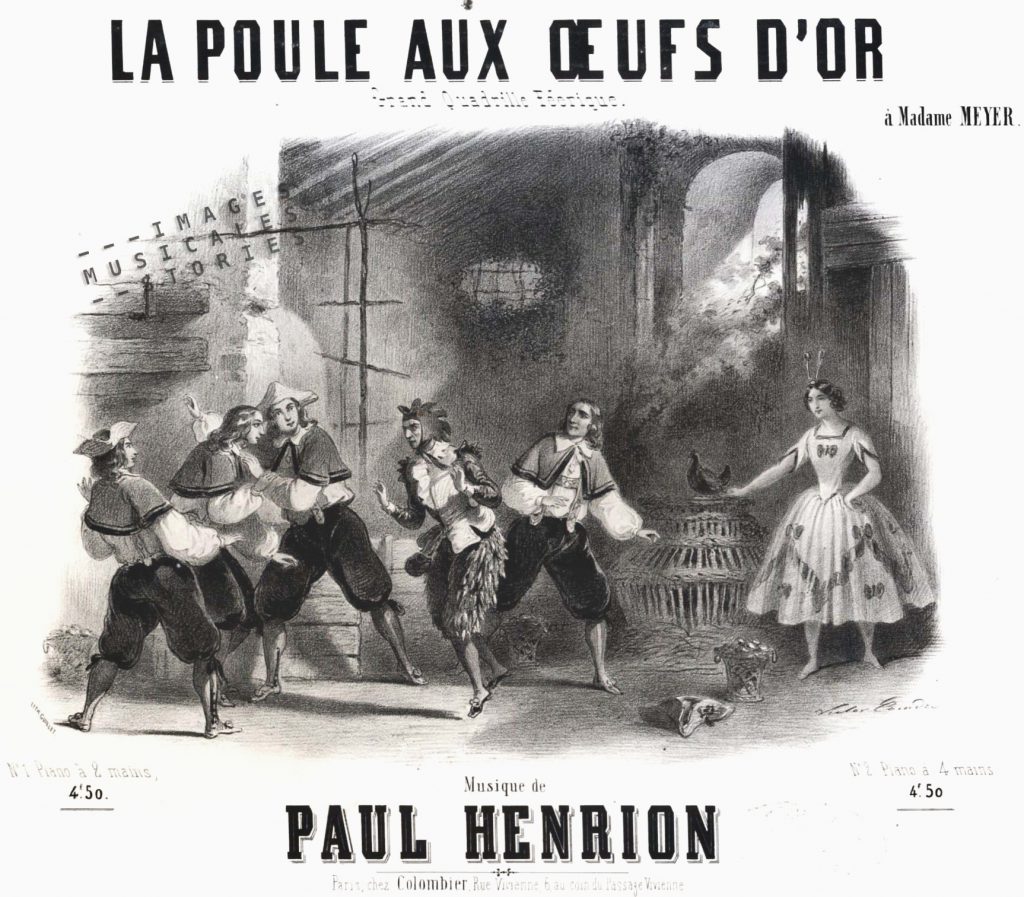

17th century Jean de la Fontaine wrote the fable La Poule aux oeufs d’or (The Hen with the Golden Eggs). It tells about a farmer with a hen that lays an egg made of gold, every single day. To discover the source of his good luck —and hoping to increase his prosperity— he opens the hen thus killing the animal without finding anything. The moral conclusion is that greed can ruin one’s good fortune.

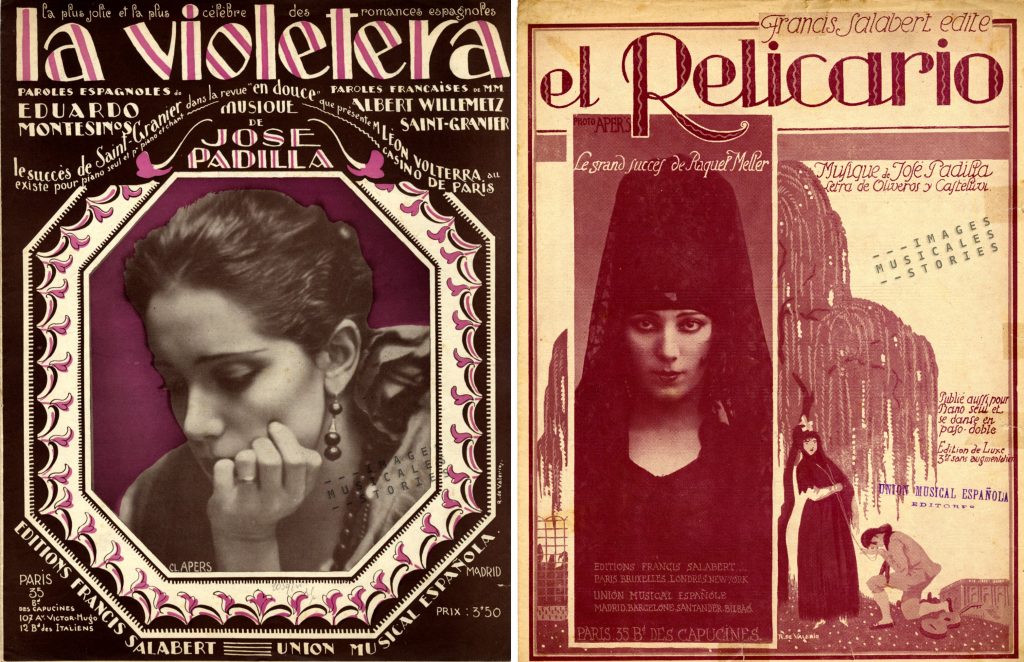

The sheet music above was composed for a play that diverges entirely from the original moral tale. This quadrille is part of a féerie, or fairy play. In a féerie the plot is subordinate and auxiliary to the spectacle and the stage effects.

This typical French theatrical genre was known for its fantasy plots and spectacular visual effects. Think smoke machines, stunning lightning and sound, and mechanical contraptions to magically change stage sets. Féeries combined captivating music, colourful ballet, pantomime and acrobatics. They developed in the early 1800s and became hugely popular in France throughout the nineteenth century. Their stories were melodramas borrowed from fables and fairy tales, with a penchant for the supernatural. A full-length féerie often ran for several hours.

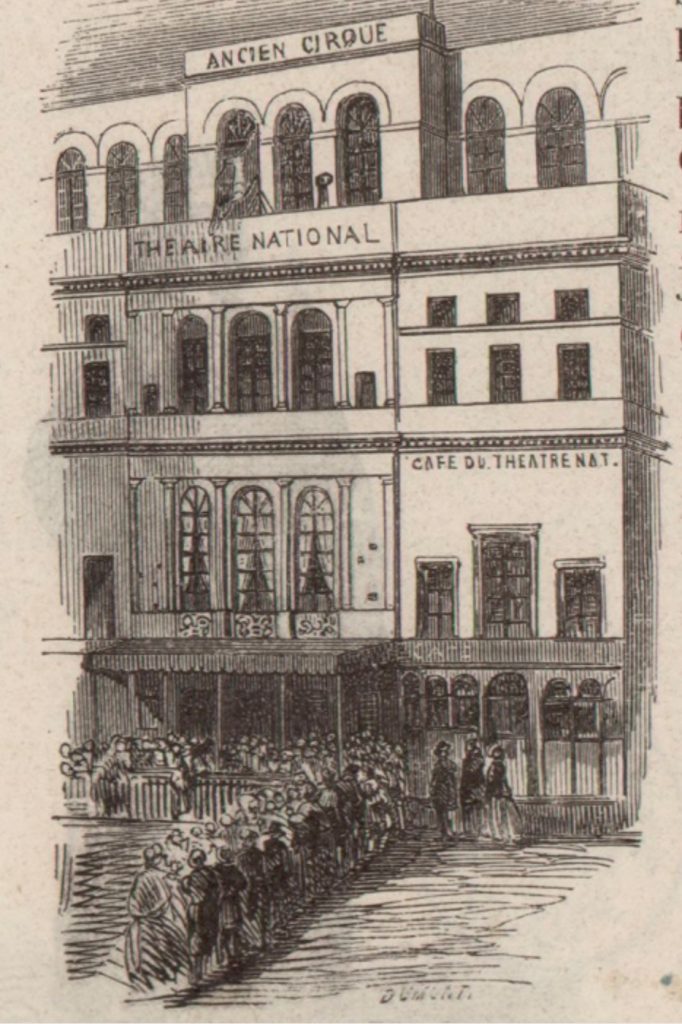

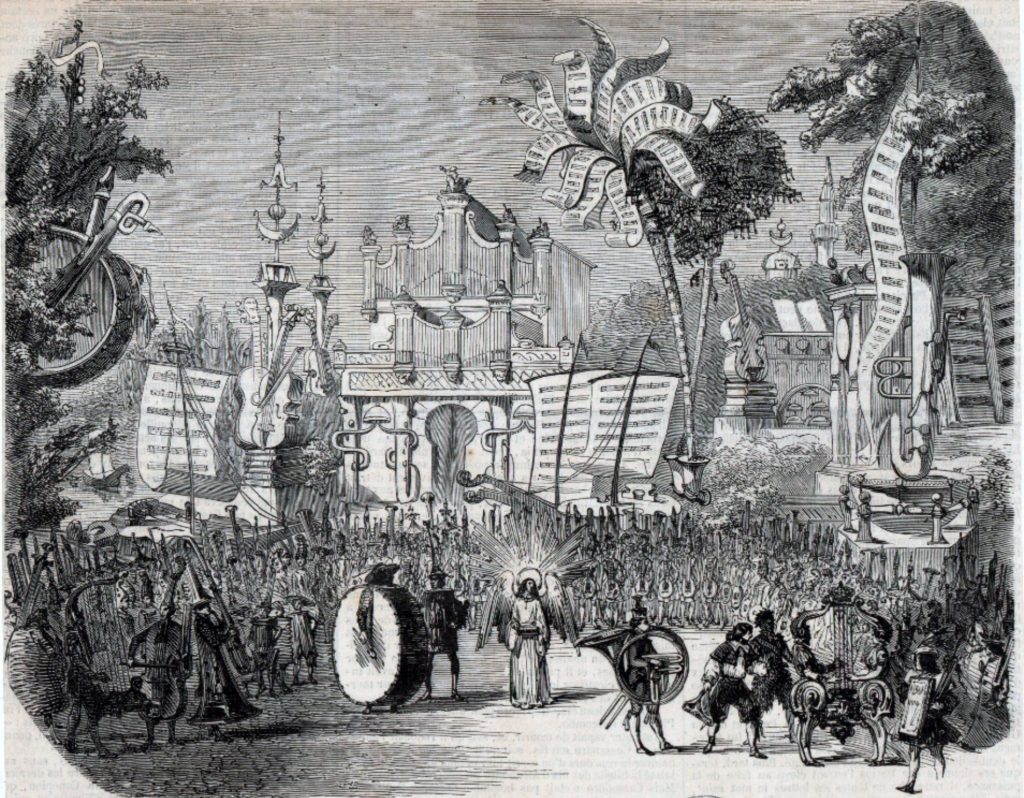

The 1848 premiere of La Poule aux oeufs d’or was at the Théâtre National on the famous Boulevard du temple, now gone but at that time the Parisian Broadway. The Théâtre National was previously a circus, and therefore commonly called Cirque national. La Poule aux oeufs d’or was a great success, if we can rely on the drawing of the crowd on the opening night. And it was relaunched in 1859.

I started reading the scenario but gave up after two pages. It was enough to realise that the play was rocambolesque: an absurd mix of ridiculous adventures, burlesque characters and the obligatory ingenue. In the mocking words of the French writer and critic Théophile Gautier: “The characters, brilliantly clothed, wander through a perpetually changing series of tableaux, panic-stricken, stunned, running after each other, searching to reclaim the action which goes who knows where; but what does it matter! This dazzling feast for the eyes is enough to make for an agreeable evening.”

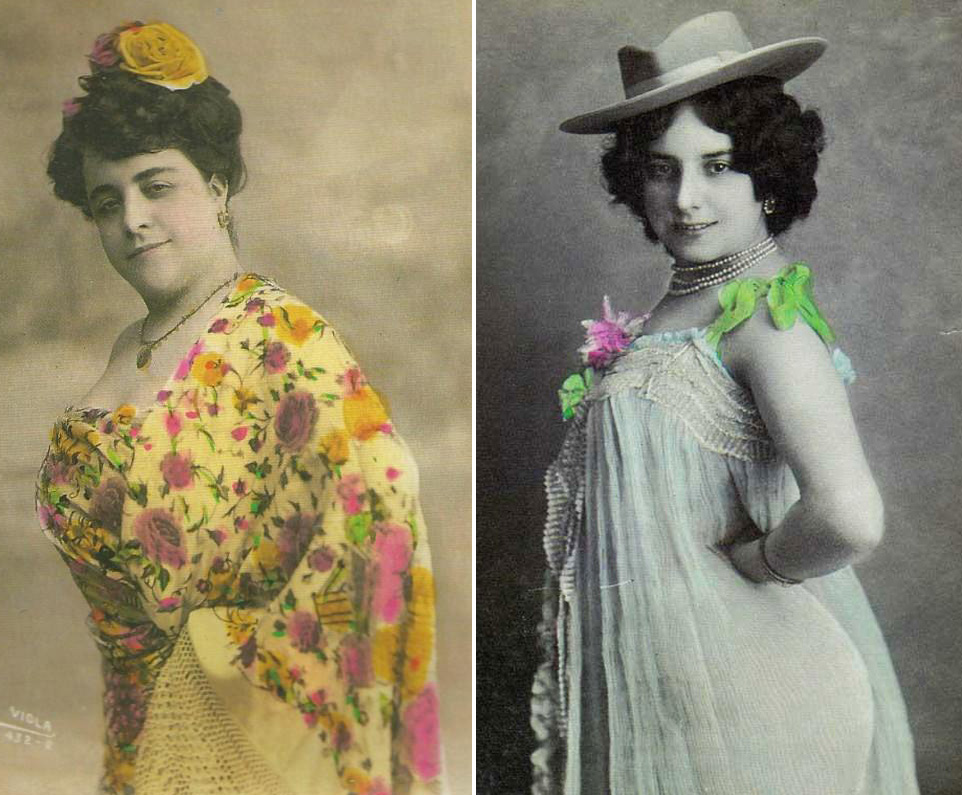

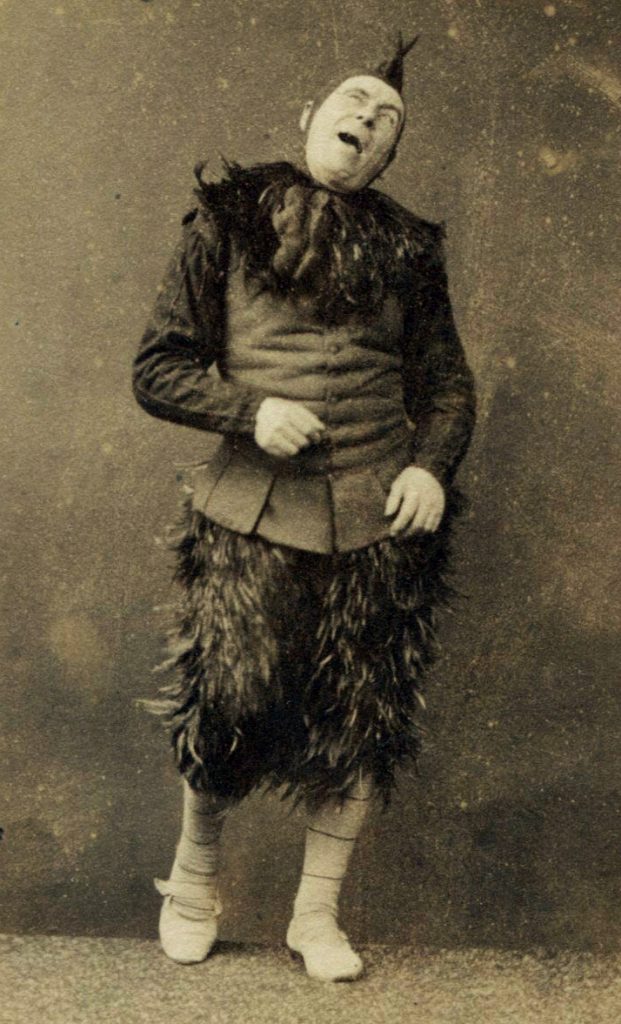

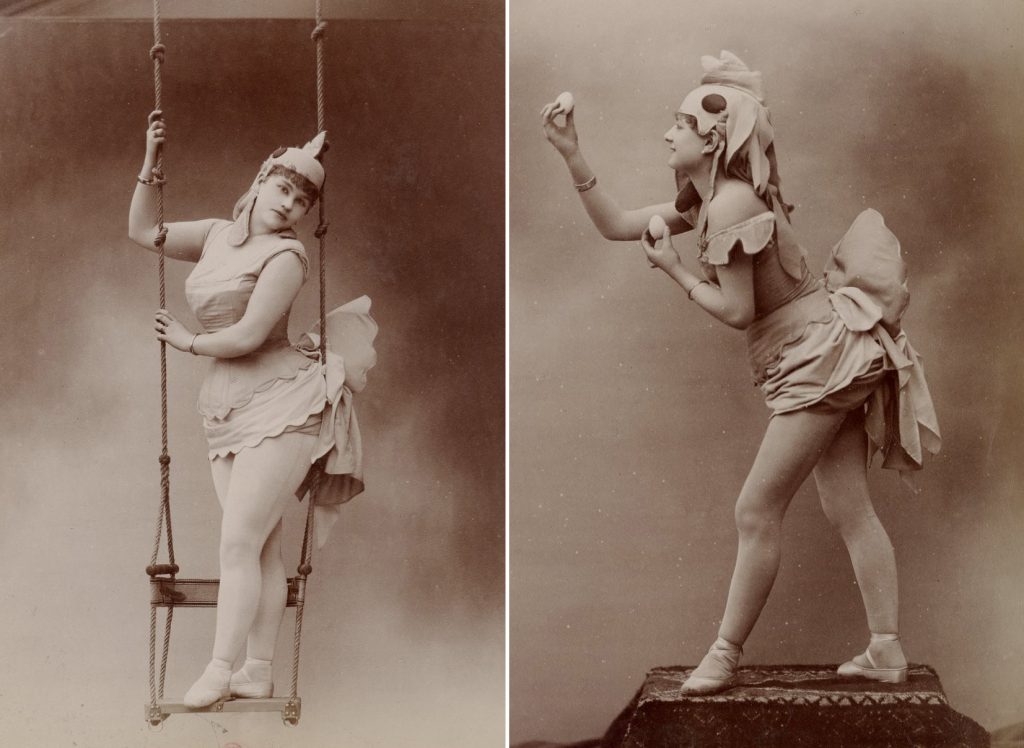

In La Poule aux oeufs d’or the characters were brilliantly clothed indeed as shown by the pretty costume drawings.

An angel and Satan provided the essential magic in La Poule aux oeufs d’or. In a féerie such supernatural forces used to drive the characters through fantastic landscapes and amazing adventures, typically with magic totems (in this case the golden eggs) used to transform people, things, and places. Wow!

But in the first place the audience came to see and appreciate the tricks. For La Poule aux oeufs d’or 24 elaborate stage settings or tableaux were built. Each one created an enchanted universe of dazzling attractions, spectacular effects and sophisticated optical illusions. In full view of the audience a cottage would transform magically in a palace. In another scene windmills would turn into gondolas while a lake emerged from the ground. Of course a large crew in charge of design and stagecraft was needed.

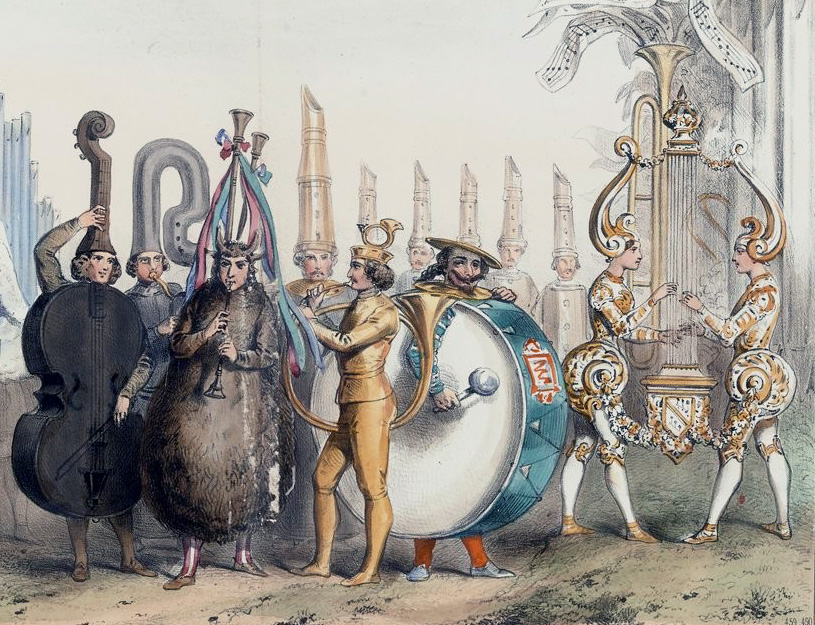

The grand finale stage led to the apotheosis: all actors, dancers, musicians and extras were united on the Île de l’harmonie (the isle of harmony) with a musical flourish.

A colourful drawing shows a detail of this tableau illustrating the clever design of the costumes and props.

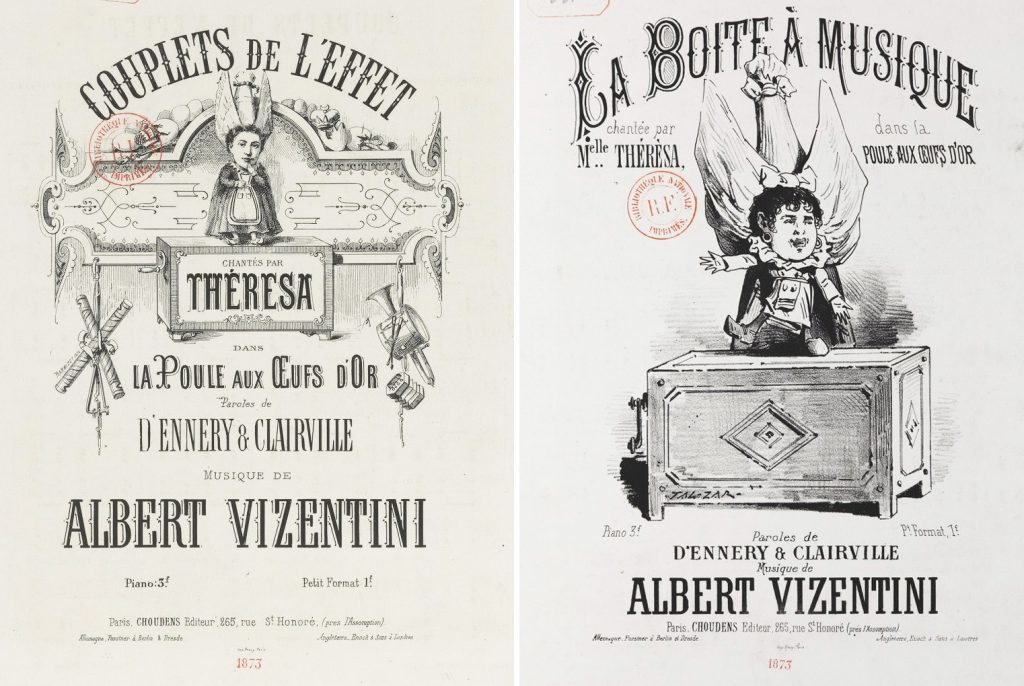

La Poule aux oeufs d’or was later staged in other productions. In the 1870s version, even the grande vedette and forcefull singer Mademoiselle Thérésa, played a role in La Poule aux oeufs d’or. This production was so successful that it would travel to London.

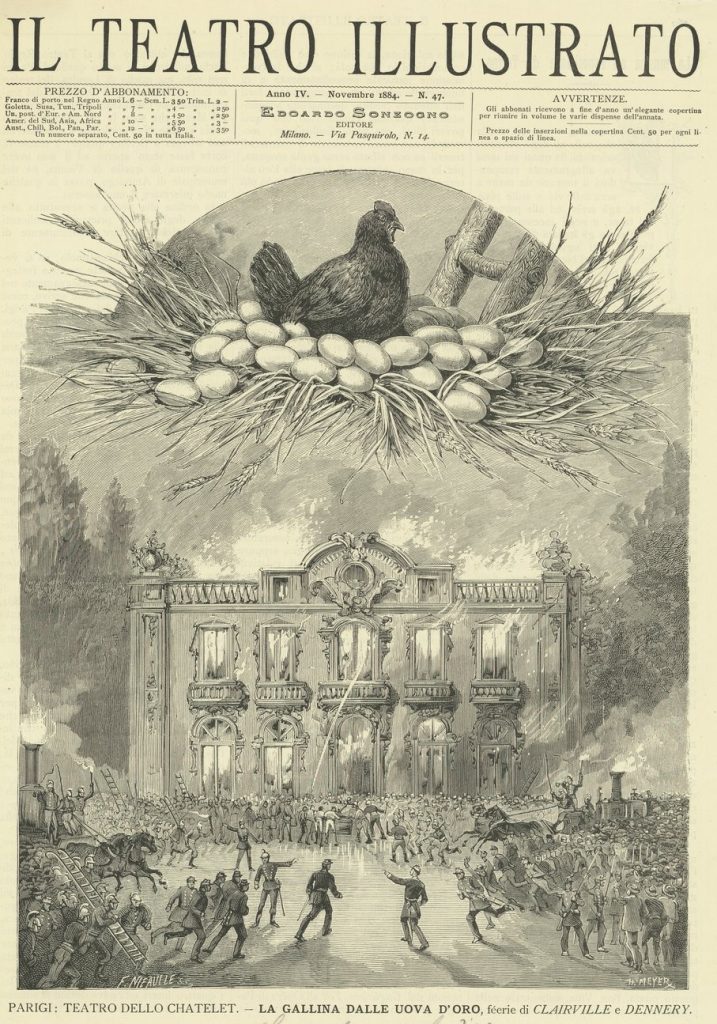

Ten years later La Poule aux oeufs d’or was restaged at the Théâtre du Chatelet.

An Italian journalist reviewing that performance reported that his jaw dropped when he saw a hundred and fifty bricklayers and carpenters, all played by children between six and twelve years, constructing a house. But what most impressed him was a house on fire extinguished by a regiment of firefighters acted by persons of short stature and he was overwhelmed by the indescribable effects of the electric light. A real nouveauté at that time. He wrote: “Just take a look at our illustration to understand how much enticement it provided to the spectator.”

In the 1890s La Poule aux oeufs d’or became a pretext to bring a little bit of nudity at the Folies Bergère. Yes, the end of the live feérie was in sight…

It fell out of popularity by the end of the 19th century, by which time it was largely seen as entertainment for children and disappeared from French stages.

The féerie quickly reincarnated as a popular cinema genre in the 1900s. The forerunner in the genre, was Méliès but the French Gaston Velle was also a prominent pioneer of special effects. He began his career as a travelling magician, before applying his illusionist skills to the cinema.

Velle’s silent short La Poule aux œufs d’or (16 min) was produced by Pathé Frères in 1905. The scenario of the film is much simpler than for the theatrical féeries and it goes back to the roots of the story. You can watch the complete film on YouTube, but we start at the apotheosis. If you haven’t time to watch the complete sequence, may we suggest to at least watch the strange 3:40 scene? Though at 7:55 (and at 8:48) you will not be less baffled…