“But now, for the first time, I see you are a man like me. I thought of your hand-grenades, of your bayonet, of your rifle; now I see your wife and your face and our fellowship. Forgive me, comrade. We always see it too late. Why do they never tell us that you are poor devils like us, that your mothers are just as anxious as ours, and that we have the same fear of death, and the same dying and the same agony–Forgive me, comrade; how could you be my enemy?” – Carl Maria Remarque

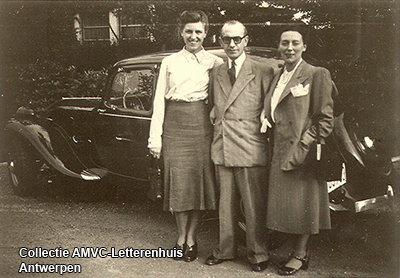

In 1929 the German novelist Carl Maria Remarque wrote his anti-war masterpiece Im Westen nichts Neues (All Quiet on the Western Front). This book about war’s physical horror was the inspiration for a Dutch song by Henri Theunisse. You can hear his wife Jeanne Horsten sing the song together with Louis Noiret.

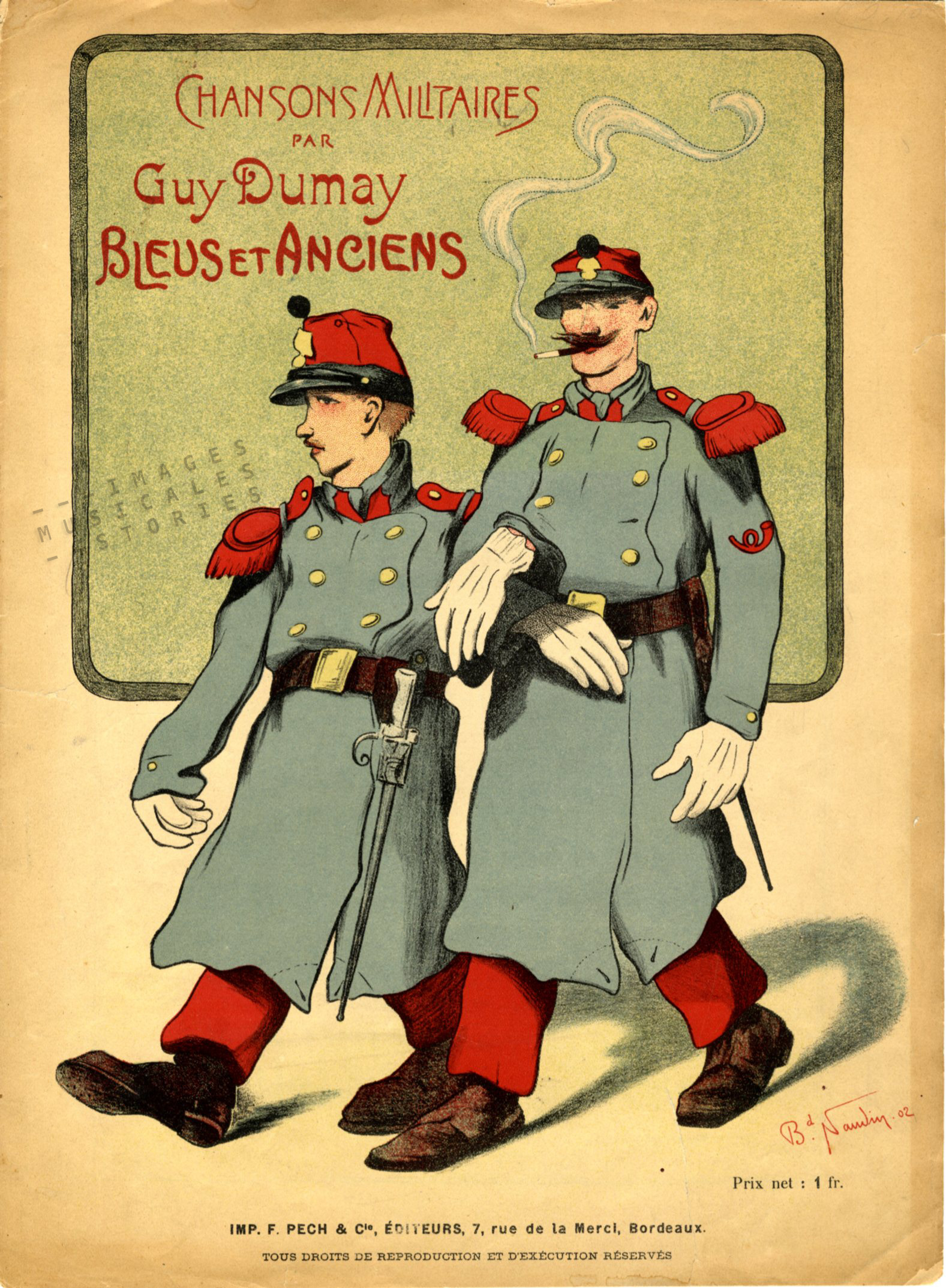

The book follows a young German, barely nineteen, and his fellow German classmates who fight in the Great War. They joined the army voluntarily after listening to the patriotic speeches of their teacher. After weeks of fighting Paul Baumer realizes that war is not glorious nor honourable, and that it makes enemies of people who have no grudge against one another. Amidst the ravages of poison gas, artillery bombs, destroyed horses and lost limbs Paul faces sorrowful disillusionment.

The book became an international bestseller. A year later, in 1930, it was adapted as an American film. It became one of the first talkies to win the Oscar for best picture. Because of the defeatist view on war’s meaningless slaughter the book and film were vilified by the emerging National Socialists In Germany. Goebbels led some Brownshirts into tossing stink bombs from the balcony of a Berlin theatre, throwing sneezing powder in the air and releasing white mice. These obnoxious pranks however went further by shouting insults to Jews and even beating people thought to be Jewish. The show was stopped. The next evenings rallies were organised against the film and similar riots erupted across Germany. The film was banned.

When I was in my early teens All Quiet on the Western Front was required reading at school. It moved me so much though that I couldn’t sleep for nights in a row. Since then I’ve been a committed pacifist.

My language teacher —who was responsible for the class’ reading list— was quite an appearance! She was a short, matronly lady with a heavily made-up face: white powder and ruby lips. Her hair was painted raven-black, which she wore in an imposing chignon. A heavy bosom completed her formidable look. At the time I thought her to be at least 100 years old. She held her husband, a now long forgotten poet and writer, in adulation. Her boundless admiration for him led her to tell us interminable stories about him and his works. Boring, but sometimes surprisingly interesting… Contrary to her old-fashioned demeanour, she was a feminist, a pacifist and atheist.

She not only taught us to appreciate literature but told us all about Simone de Beauvoir’s Le deuxième sexe and the role of Bernadette Devlin in the student-led civil rights movement in 1968. At the same time, as she found us an unruly bunch of young teenage girls, she taught us about etiquette, which magazines were appropriate for young women, and how to decorate our future homes. After all, you wouldn’t want to live in a petty-bourgeois interior, now would you?

Speaking for myself, I’m inclined to say: mission accomplished Mrs R.! Except maybe for the etiquette thing.

This song is for you.