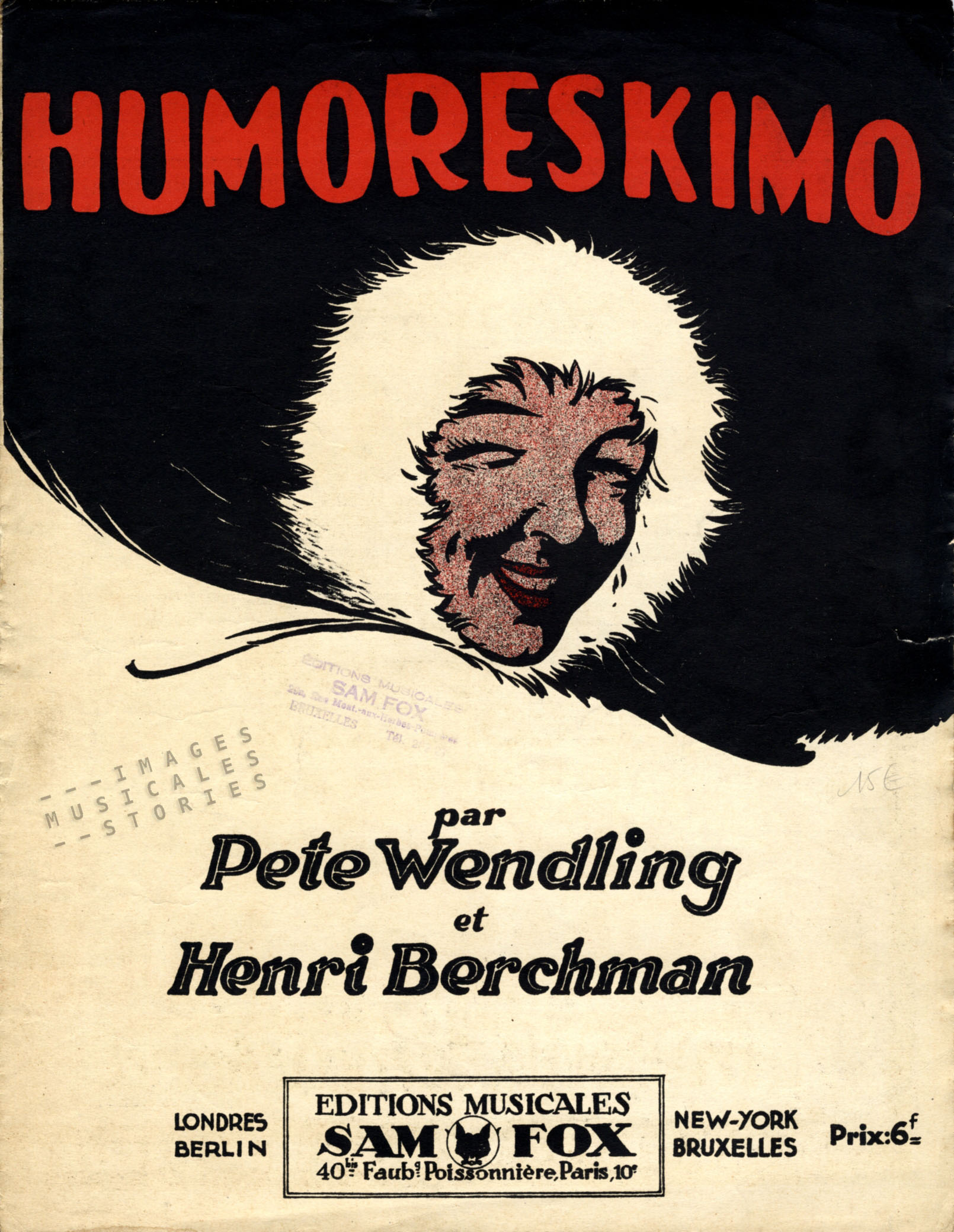

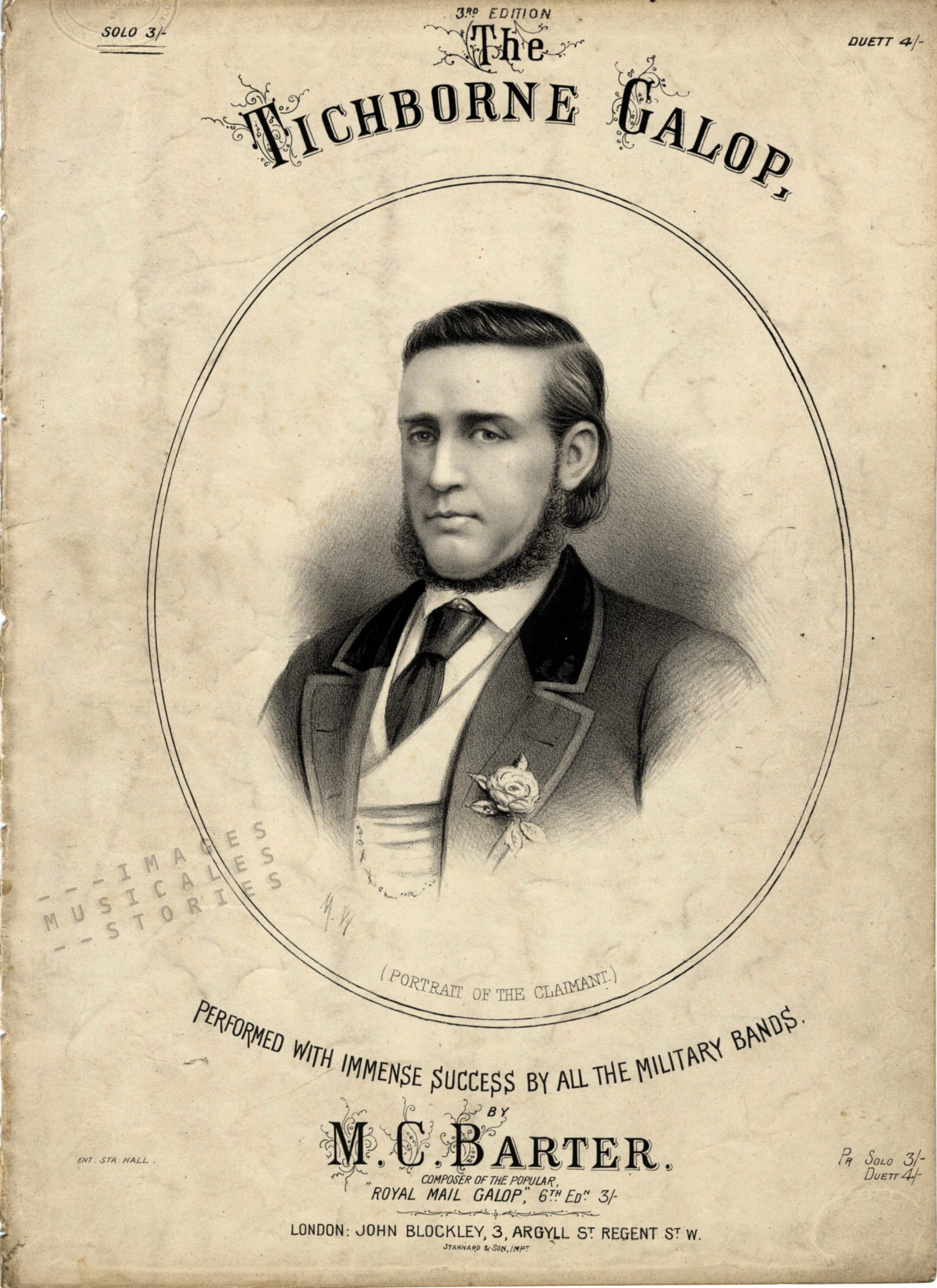

This cover from our sheet music collection bears a portrait of the Claimant to the Tichborne title and fortune. The story about the sensational reappearance of the long-lost Roger Tichborne captivated all of England’s Victorian public. The tale is still shrouded in mystery, at least as to how people are craving to be fooled, again and again…

The aristocratic Roger Tichborne grew up in Paris and spoke English with a pronounced French accent. As a young man he was travelling in South-America when he learned that his father had succeeded to a baronetcy. Roger would be next in line to inherit the tile. Shortly after receiving this news in 1854, Roger sailed to Jamaica but never arrived. Four days after his departure from Rio de Janeiro, the wreckage of his ship was found without a sign of its passengers: Roger Tichborne was lost at sea.

Roger’s mother clung to the rumour that some of the passengers on the wrecked ship had been picked up by a passing vessel on its way to Australia. In 1862, when her husband died, she desperately searched for news from her son. Her advertisement in Australian newspapers described Roger as being rather tall with light brown hair, blue eyes and a delicate constitution. It also mentioned that Roger was the heir to the extensive estate of the deceased Sir James Tichborne. Lo and behold, in 1865 an Australian announced that he had lived under the pseudonym of Thomas Castro, and now claimed that he in fact was Roger Tichborne. He started corresponding with his English ‘mother’.

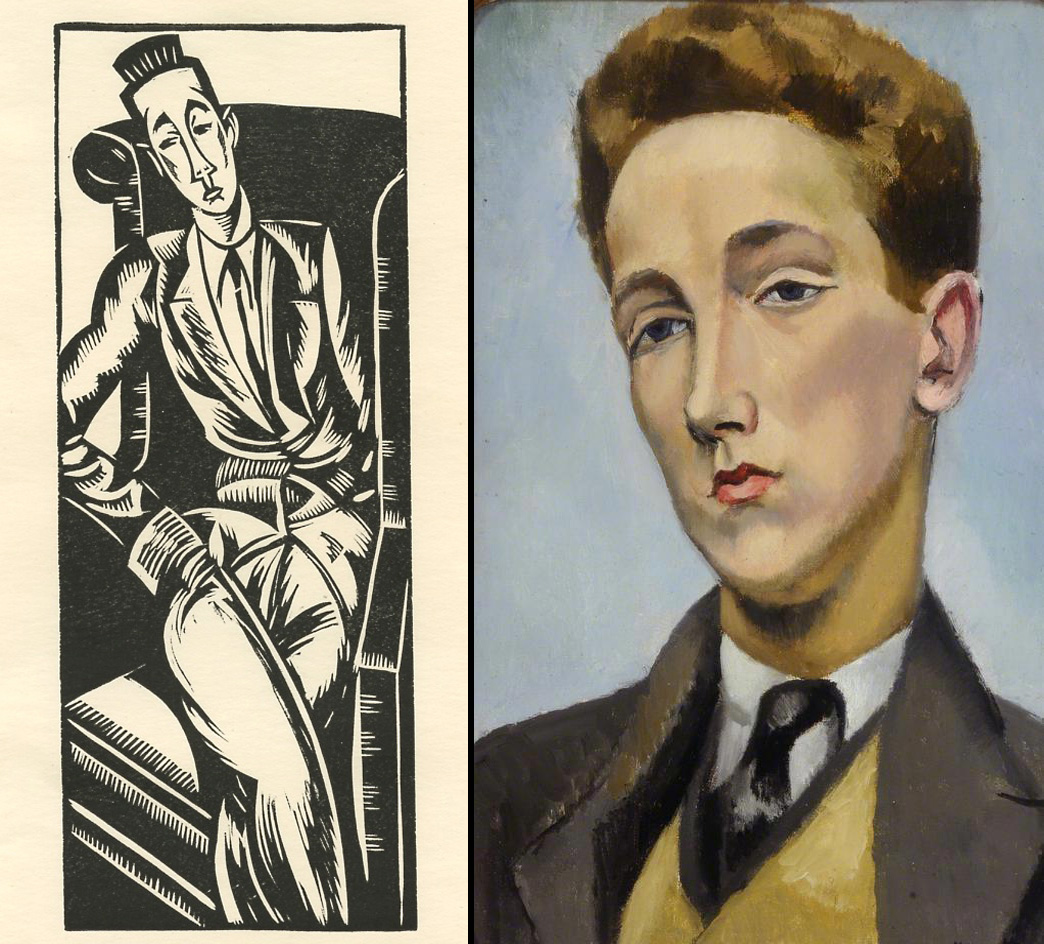

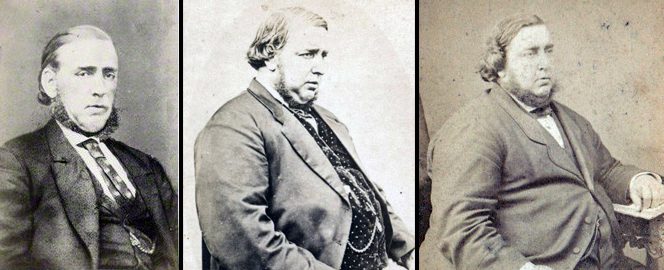

Roger Tichborne’s last picture taken in South America showed a thin, somewhat effeminate man. So Thomas Castro wrote to his wannabe mother that he had gained some weight. When he set sail – the voyage paid by Mrs Tichborne of course – he weighed 100 kg and by his arrival in England he had put on another 30 kg.

He then did an odd thing. First of all he went to Wapping in East London where he inquired after the family of his Australian friend, Arthur Orton. After he learned that the Orton family had left the area he met Mrs Tichborne in Paris. Although by that time his weight had reached 150 kg, the excitable mother immediately clasped him to her breast, as if she instinctively had recognised her son. Roger’s Parisian tutor was more percipient: he declared the Claimant an impostor and disclosed his ploy as a fraud. Nonetheless, the gullible Lady Tichborne settled him a yearly income and accompanied him to England.

The rest of the family was very sceptical and objected to the Claimant because of the following reasons:

– his letters were illiterate whereas Roger was well educated;

– he didn’t speak nor understand French;

– he had a Cockney accent;

– he didn’t recognise his family;

– he didn’t have Roger’s tattoos;

– his picture was recognised in Australia as that of Arthur Orton, a bankrupt butcher.

When his ‘mother’ died in 1868 the prodigal son was deprived of his money. In 1871 he claimed his heritage in a tribunal. But he lost his case (not his weight though because by then he tipped the scales at just over 200 kg) and was accused of perjury. A criminal trial followed in 1873 upon which the Claimant’s fraudulent world fell apart: the jury found him guilty and he was exposed as Arthur Orton. He was sentenced to fourteen years in prison.

The two trials were a huge sensation giving rise to extensive media coverage. Bizarrely the Tichborne Claimant became a working-class hero, a defier of the establishment. His supporters, the Tichbornites, saw him as a victim of the aristocratic elite in cahoots with the government, the legal profession and the queen herself. A poor, humble man like the Claimant was denied the right to belong to the la-di-da upper class. His cause became a large popular movement and a Tichbornite candidate even won a seat in Parliament.

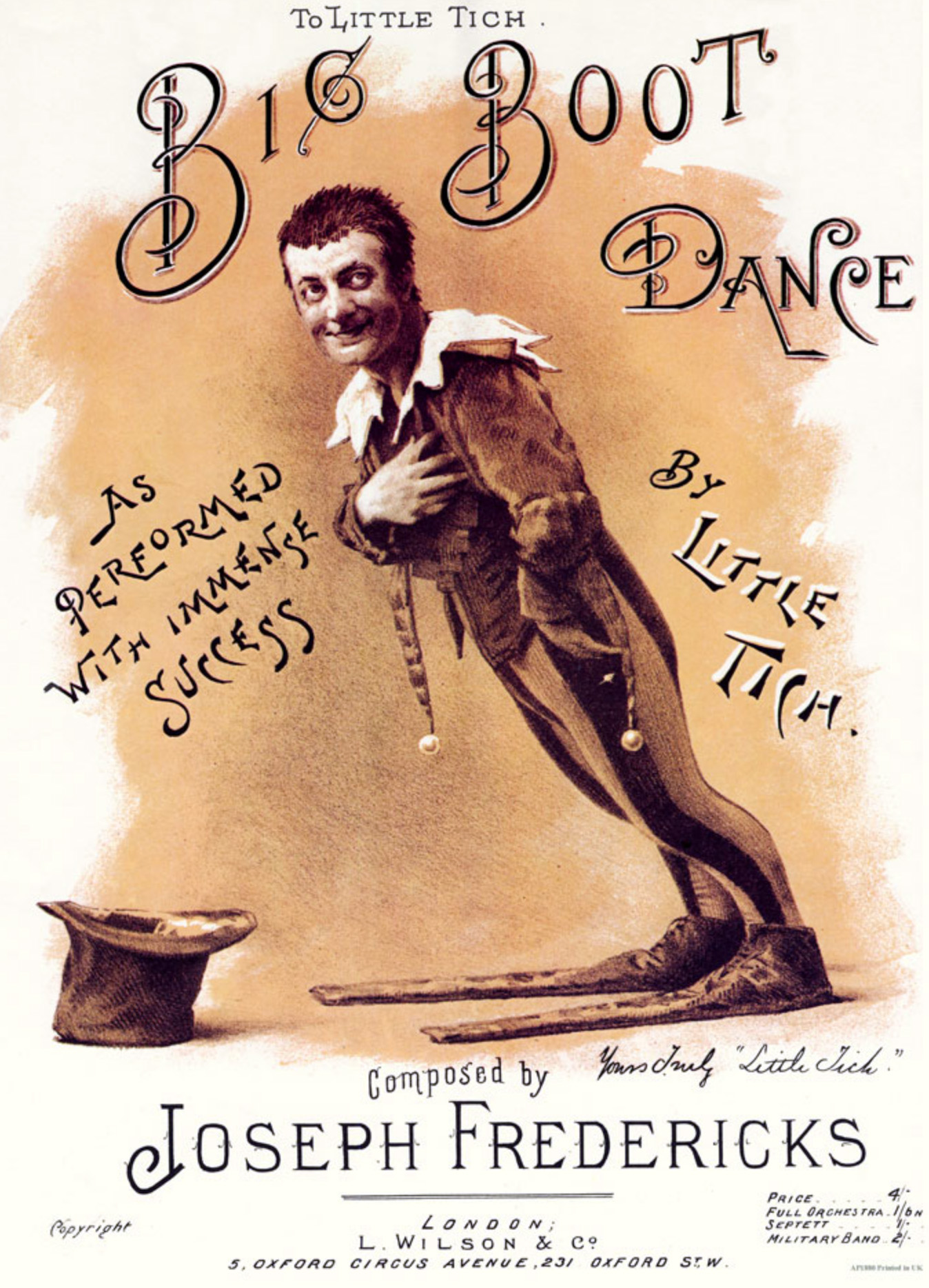

After his release from prison the Claimant, who had already revelled in public attention during his trials, toured with circuses and appeared in music halls. A real music-hall artist, Harry Relph, who was 1,37 m tall, adopted the stage name Little Tich in contrast to the bulky appearance of the Claimant. Little Tich became a successful British comedian, specialising in energetic dances, comedy numbers and songs.

The comedian’s talent sparklingly comes to life with his popular routine act in ‘Little Tich et ses Big Boots’, a short film made by the Frenchman Clément-Maurice for the 1900 World Fair in Paris. Don’t try this at home.