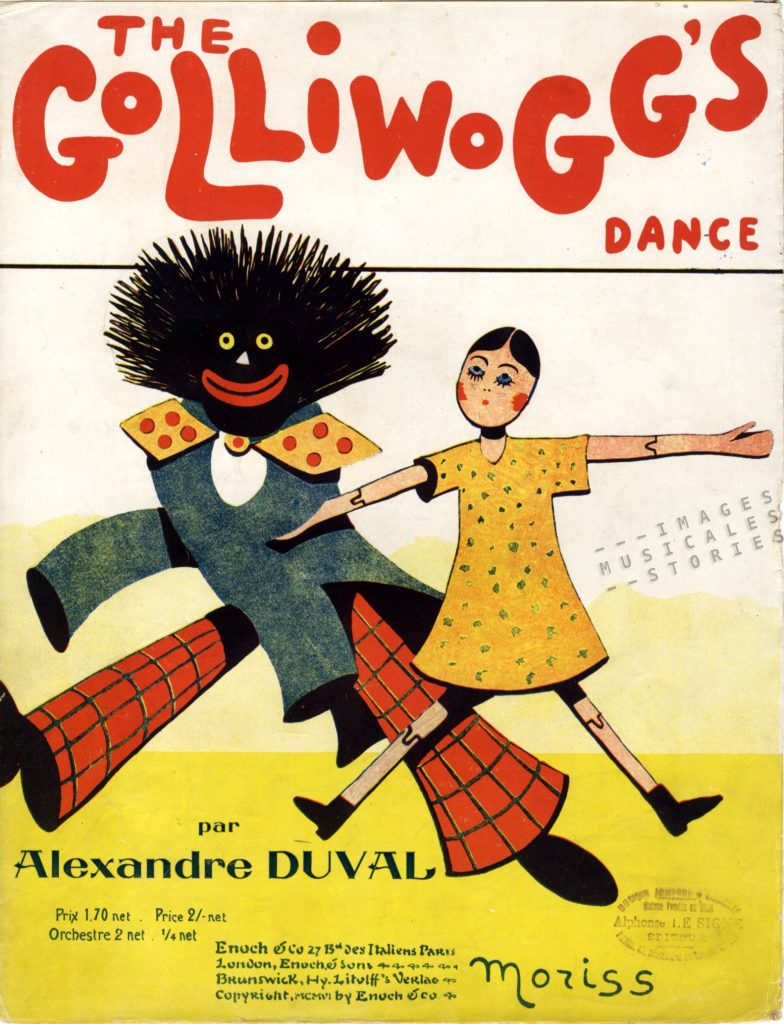

The colourful cover for Alexandre Duval‘s The Golliwogg’s Dance (1906) was drawn by illustrator, cartoonist and comedian Maurice Boyer, aka Moriss (1874 – 1963). The music and cover clearly wanted to build on the success of the series of children’s picture book illustrated by Florence Upton.

This series around a ‘Golliwogg‘ character started in 1895 when the American-

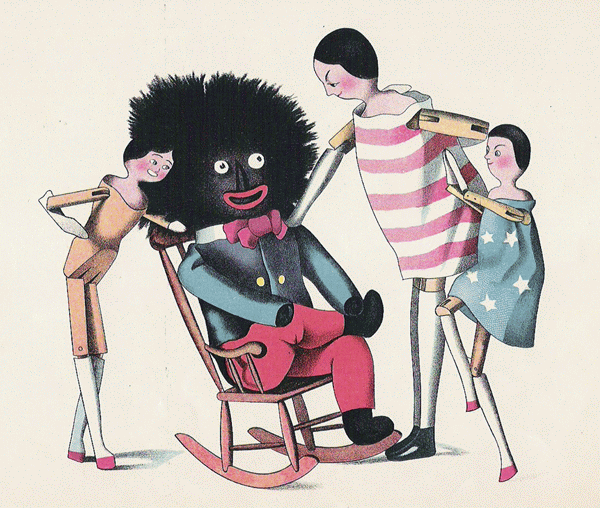

Unluckily, Florence and Bertha did not trademark the Golliwog and soon, following the success of the children’s books, all kinds of doll manufacturers began producing Golliwog dolls. They were stuffed black figures, with a friendly look but having a bad hair day, wearing red pants and a bow tie. In England during the first half of the twentieth century, the Golliwog became almost as popular as the Teddy Bear.

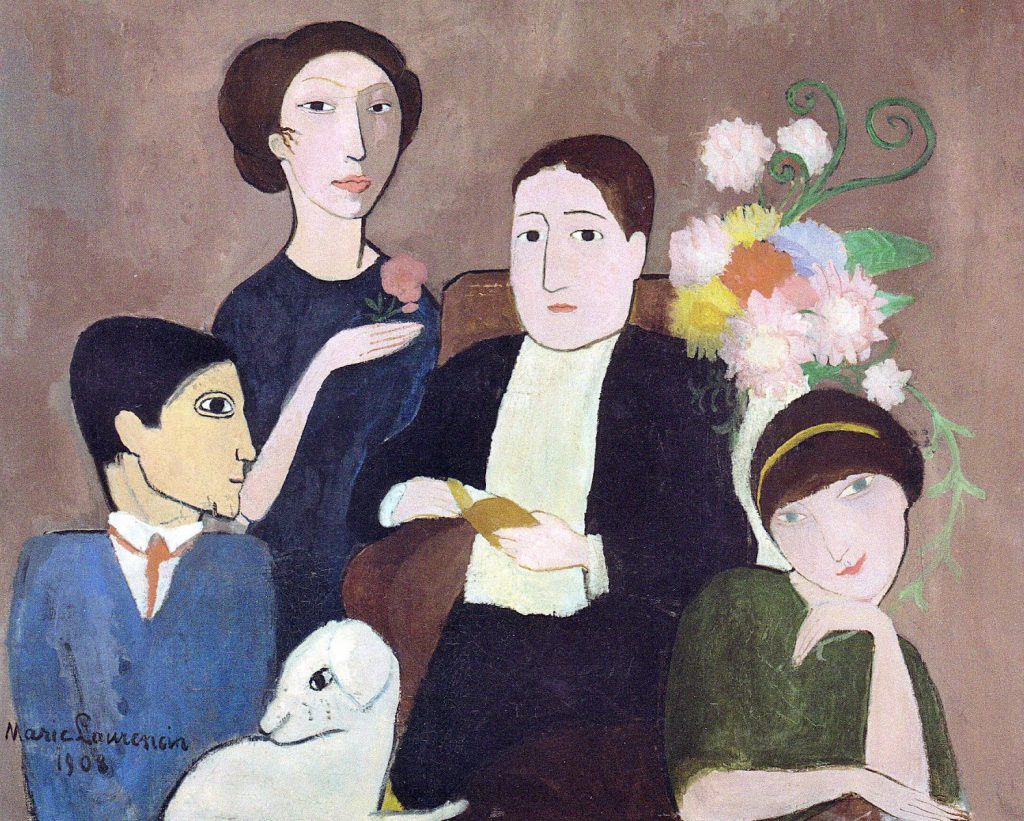

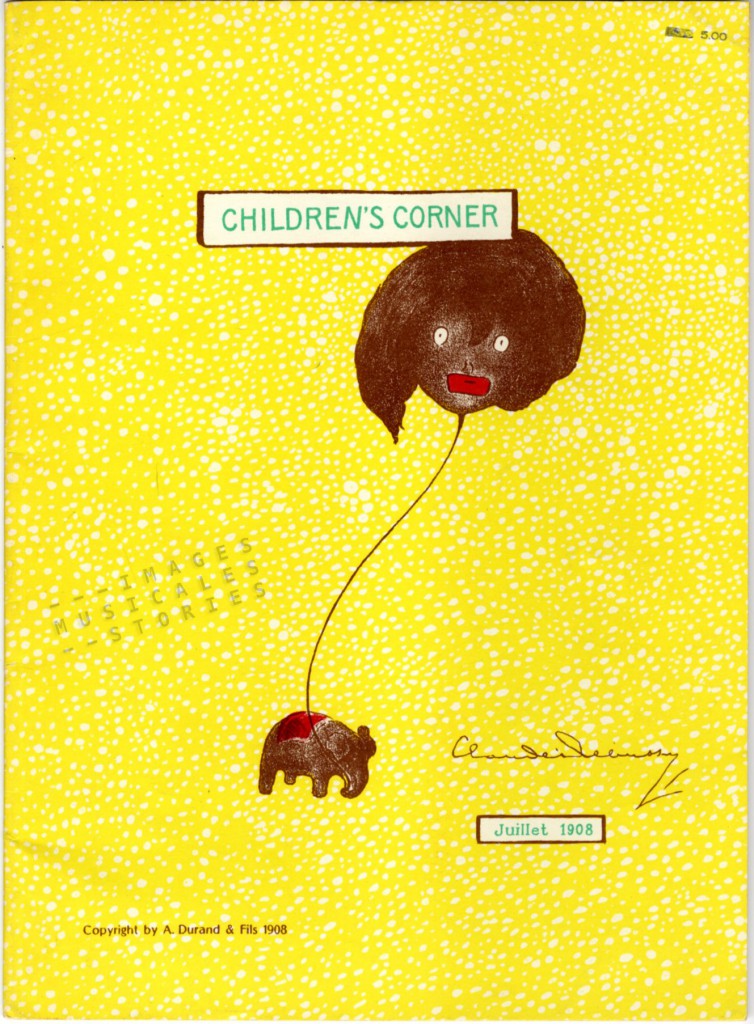

In France the Golliwog inspired Claude Debussy. Golliwog’s Cakewalk is the sixth and final piece in his piano solo suite Children’s Corner (1908). Debussy dedicated this suite, about toys coming to life, to his much beloved daughter Emma, nicknamed Chouchou. The cover with a small elephant holding a gigantic Golliwog balloon is rather surrealistic, and was drawn by Debussy himself. The Golliwog’s cakewalk is clearly influenced by Afro-American ragtime and jazz.

The doll created by Florence Upton had everything of the blackface minstrel tradition: black skin, big mouth, frizzy hair, a festive dress with bow tie and tailcoat jacket. In 1913, the always wayward ballet dancer Alexander Sacharoff made his own ‘white’ interpretation of Debussy’s Golliwog. In it he patently declared his love for outrageous costumes and wigs.

While Florence’s original Golliwog character was jovial and friendly some later specimens were sinister or menacing. This is also true in Marcel L’Herbier’s short phantasy film from 1936. A little girl, together with her toys, watch the fearful dance of a Gollywog-Jack-in-the-box. The world-famous Alfred Cortot is at the piano, playing three pieces from Debussy’s Children’s Corner. The Golliwog’s Cakewalk starts at 5:32. That scene is preceded by a message —now considered overtly racist— warning the audience to certainly applaud the ‘terrible nègre‘ who can otherwise become very mean.

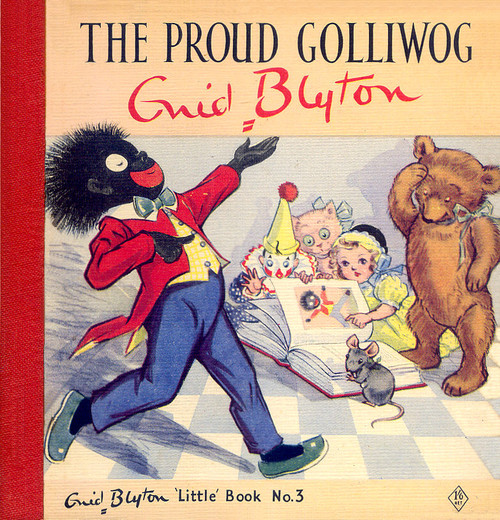

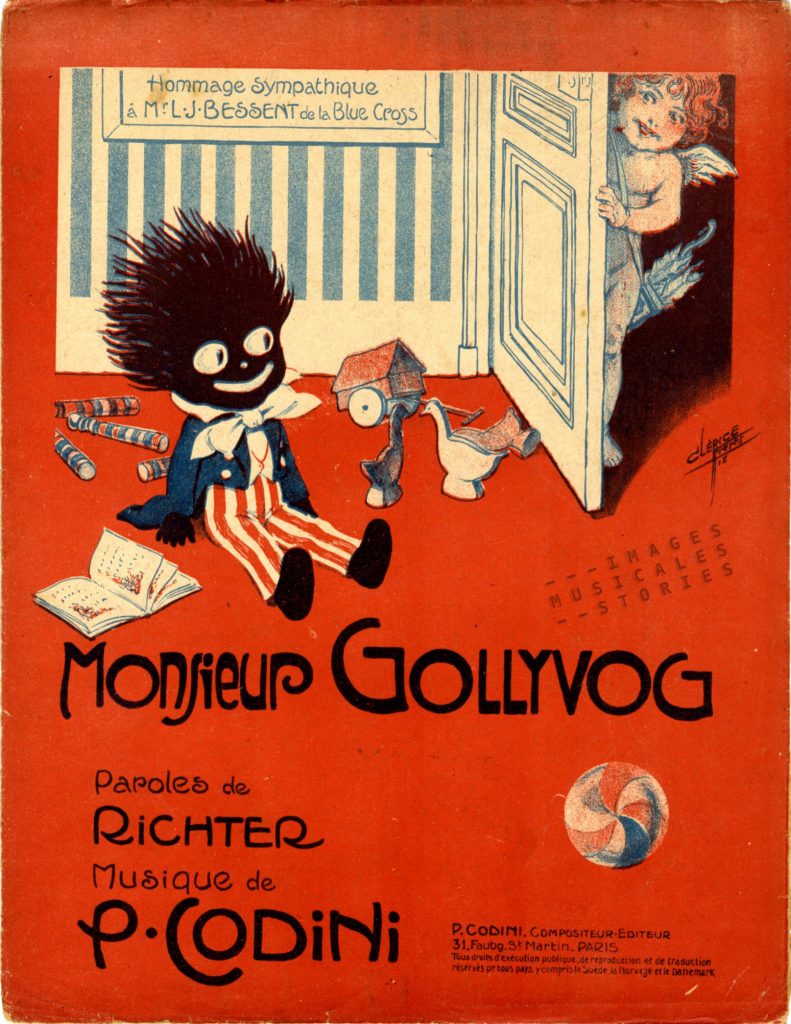

Even the famous Enid Blyton also incorporated a rather evil Golliwog in her books. But it was later banished from revised editions. The popularity of the Golliwog contributed to the spread of the blackface iconography in Europe. Unaffected by a few fearsome embodiments, European children adored their doll. Like their parents they were racially insensitive and not aware that the blackface itself represents a demeaning image of black people. The prolific illustrator Clérice even paired a gentle ‘Gollyvog‘ (yes, the difficult double-U for the French ) with his characteristic cupid.

The popularity of the Golliwog contributed to the spread of the blackface iconography in Europe. Unaffected by a few fearsome embodiments, European children adored their doll. Like their parents they were racially insensitive and not aware that the blackface itself represents a demeaning image of black people. The prolific illustrator Clérice even paired a gentle ‘Gollyvog‘ (yes, the difficult double-U for the French ) with his characteristic cupid.

And of course the Golliwog was also used for marketing other things than sheet music.

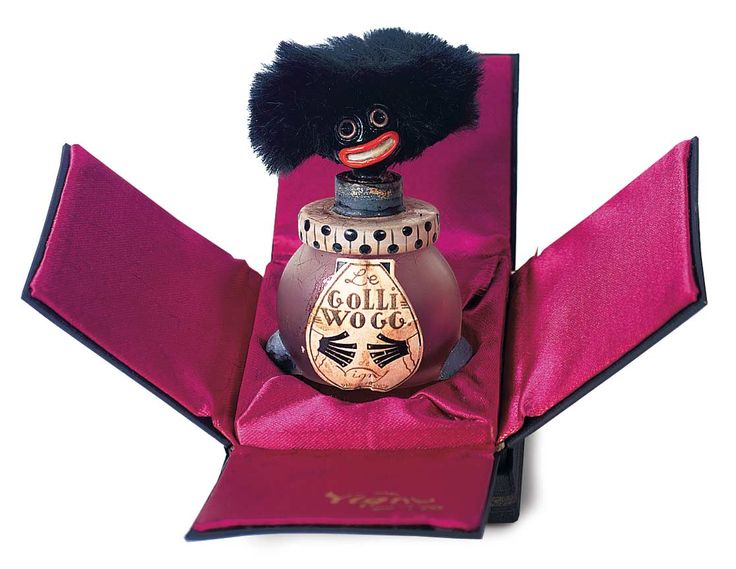

De Vigny created a spicy, floral, oriental perfume for ladies. The fragrance was launched in France in 1919 as ‘Golliwogg’. Its bottle was designed by Michel de Brunhoff, who worked for Vogue France. He was the brother of Jean de Brunhoff, creator of Babar. The top of the stopper was fitted with real seal fur. These flasks were sold until the late 1960s. Robertson & Sons, a British manufacturer of jams and preserves, began using the Golliwog —or Gollie as the British lovingly called him— as the company’s mascot in 1910.

De Vigny created a spicy, floral, oriental perfume for ladies. The fragrance was launched in France in 1919 as ‘Golliwogg’. Its bottle was designed by Michel de Brunhoff, who worked for Vogue France. He was the brother of Jean de Brunhoff, creator of Babar. The top of the stopper was fitted with real seal fur. These flasks were sold until the late 1960s. Robertson & Sons, a British manufacturer of jams and preserves, began using the Golliwog —or Gollie as the British lovingly called him— as the company’s mascot in 1910.

The advert above was distributed as late as 1984 when it became muddled by protests, indignation and outcry against its racism.

The Golliwog was also known as a classic contortionist act. A sketch by the Florida Trio from the early fifties gives an idea of the torturous feat. An extremely double-jointed figure in a golliwog costume is doing amazing foldings and bendings. Don’t try this at home!

Let’s end with a quiz question. Into what name did the Golliwogs change their name in 1967, the year in which they recorded their single Tell Me? Not too difficult, if you ask me. Just listen to the first two singing notes and you’ll know the answer.