Heinrich Strecker (1893-1981) is an Austrian composer. He was born in Vienna but was educated in Belgium in a Catholic school run by German brothers. Strecker would later remember his school years: “Given my extraordinary musical talent my teachers gave me free lessons in piano, cello, tenor horn, trumpet, flugelhorn, horn, trombone and organ. Besides I was trained to play the violin upon a master level. I was soon regarded not only as the best musician but also as the best singer of the school. No feast day went by without me singing Gregorian chants as a soloist in Church or performing before the highest ecclesiastical and secular dignitaries like the King of the Belgians for whom I played, as a climax, my own composition, a violin concerto.” Ahem…

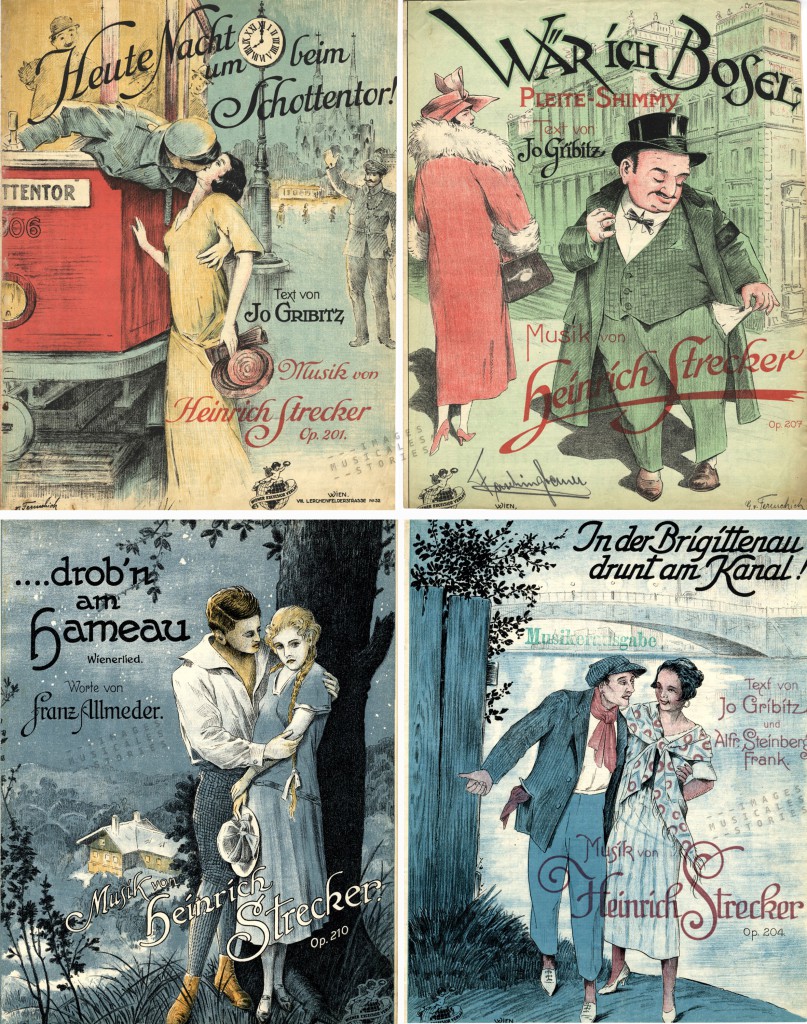

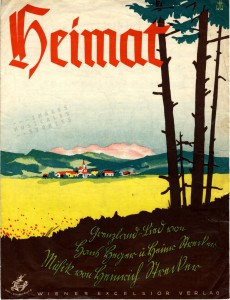

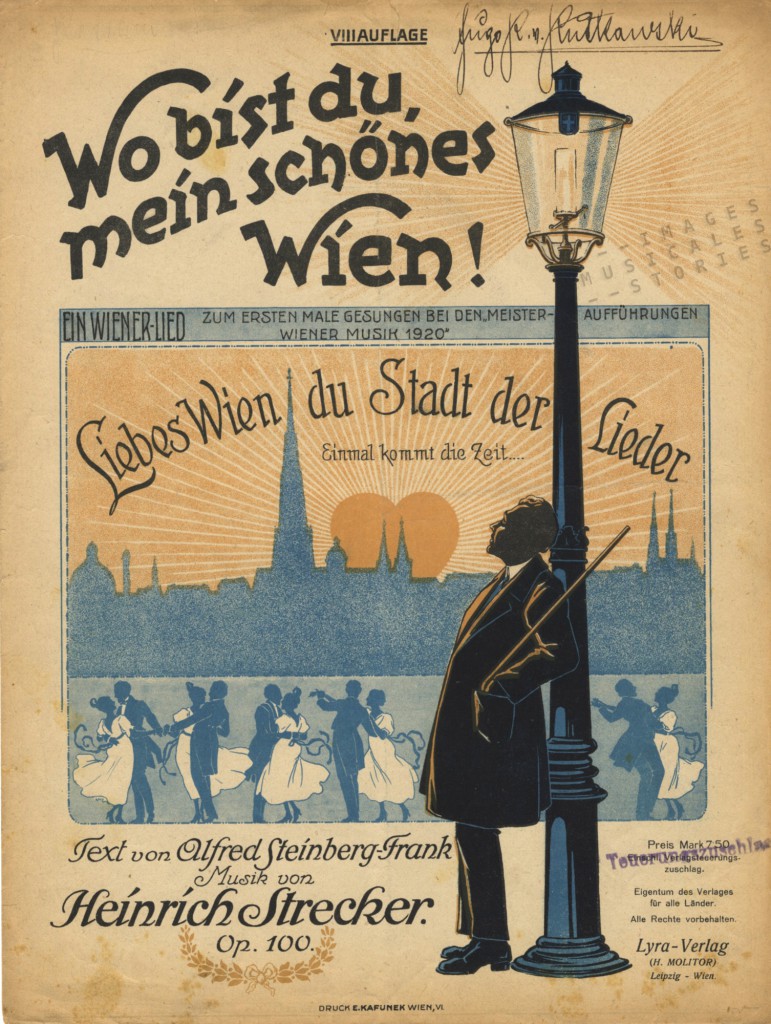

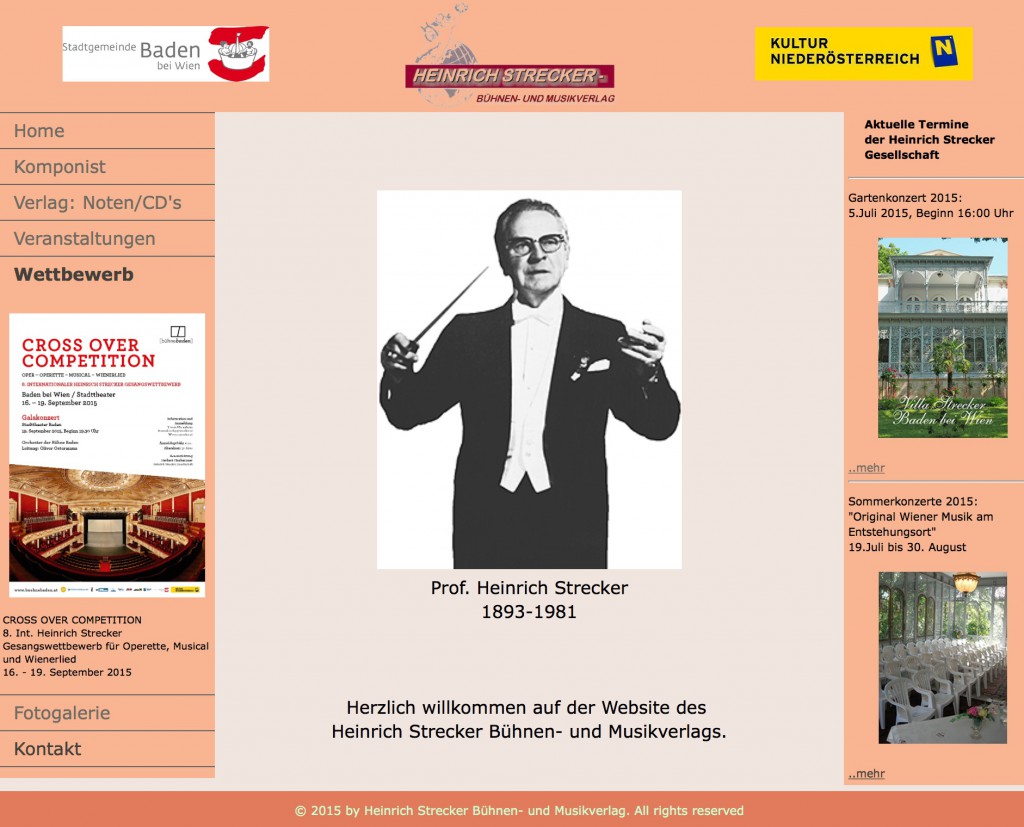

In 1910 Strecker returned to Vienna and would become the self-proclaimed saviour of the Wienerlieder (Viennese Songs). Wienerlieder were critical, ironic, funny songs about life in and around Vienna, sung in the local dialect and blending humour with melancholy. These popular songs had known their heyday in the 19th century’s last quarter. According to Strecker the Wienerlied had little chance against the modern foxtrot: “Publishers had only a pitying smile for my futile struggle for the dying Wienerlied”. Still, Heinrich Strecker sensed the financial potential of its revival and in 1922 founded his own music publishing company, the Wiener Excelsior Verlag. He composed operettas and hundreds of songs which “glorified Vienna and began their triumphal march throughout the world”.

We are coming to the gist of our story. In 1933 Strecker became member of the NSDAP, the German Nazi party. At that time the Austrian government tried to suppress National Socialism, and his Nazi affiliation cost Heinrich Strecker six months of detention in 1936. After his release he conveniently made an extended tour in Germany. Strecker returned to his homeland in 1938, right after the Anschluss. Our composer welcomed this annexation of Austria to the German Reich with two songs: Deutsch-Österreich ist frei! and Wach auf Deutsche Wachau. This last song became also known as the Ostmarklied, ‘Ostmark‘ being the new Nazi name for Austria. The words of the song allow little doubt as to Strecker’s sympathies:

- Von Burg zu Burg die Frage geht,

wann denn die Ostmark aufersteht,

ob auch der Bruder endlich heimwärts fand,

heim in das große Vaterland? -

- From castle to castle the question spreads,

when will Ostmark rise again,

whether the brother finally found home,

back into the great fatherland?

- From castle to castle the question spreads,

No wonder that this Ostmarklied became a Nazi battle song. The same ‘honour’ also befell Heimat, another one of Strecker’s successes.

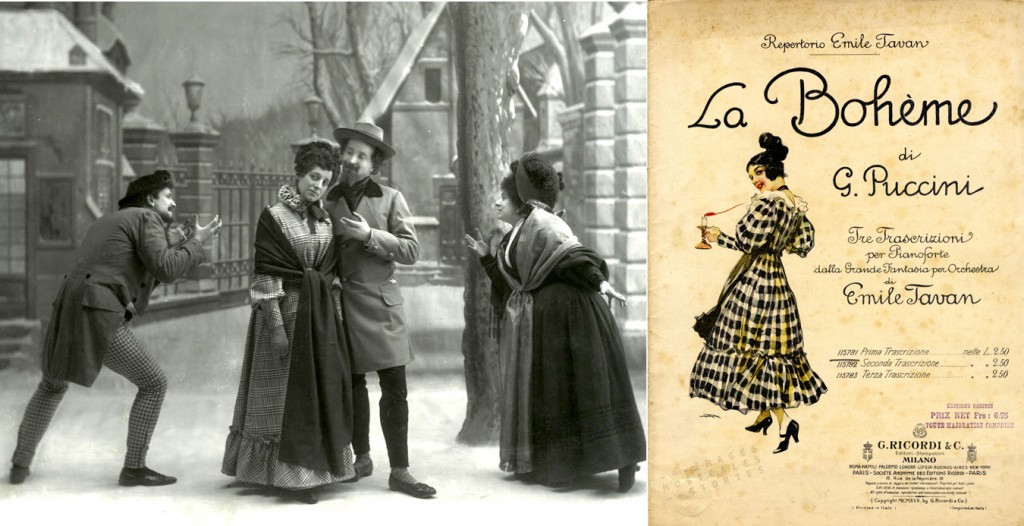

Tellingly, it was in Bremen (Germany) that his operetta The Eternal Waltz premiered in February 1938. Not until three months later, after the Anschluss, could Strecker triumph its premiere at the Vienna Volksoper. By that time Nazi rules already had started the persecution in the Austrian musical world. Jews were prohibited to own commercial enterprises. The work of Jewish composers and authors were banned: performances were prohibited as was the sale of their sheet music. Their printed scores were destroyed or marked as unavailable.

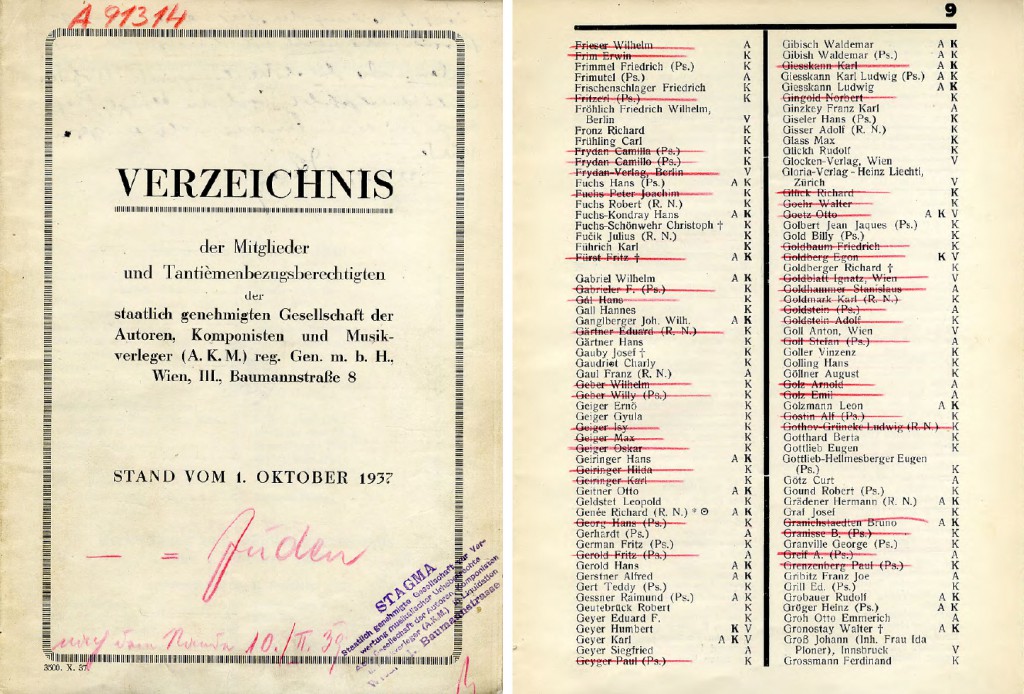

Barely three months after the annexation, Heinrich Strecker became vice president of AKM, the music copyright agency. It was then already fully compliant with Nazi rules. Earlier, in March 1938, AKM’s council had been dismissed and a Commissar Chairman appointed. Immediately a questionnaire had been sent to all members asking racial and religious questions. In June of the same year the AKM was replaced by STAGMA, the society for musical performing rights from Nazi Germany. STAGMA was administered by the Reichsmusikkammer directed by Joseph Goebbels.

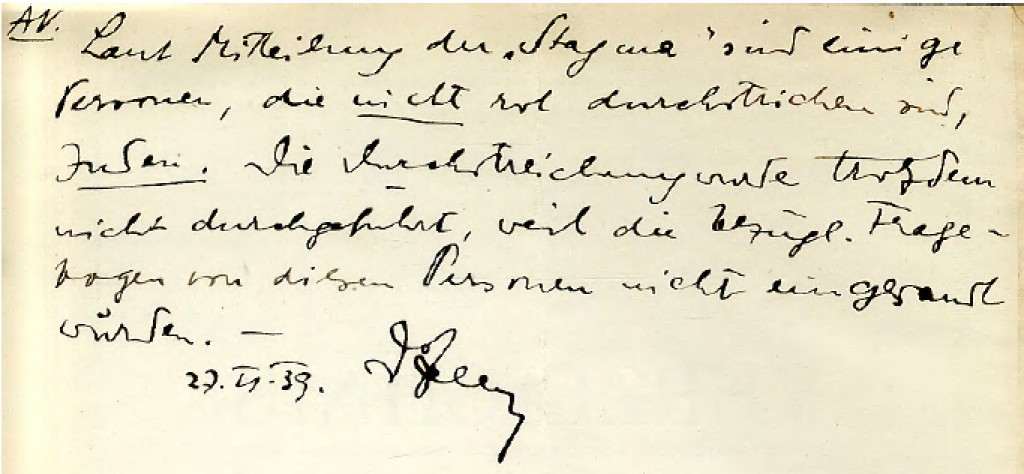

In 1939, in a booklet containing an AKM membership directory someone deleted the names of Jewish members by hand with a neat red line. The legend written on the booklet reads: ‘- = Jüden’. These were to be blacklisted! A handwritten note inside this booklet chillingly explains that some members had not yet been crossed off because they had not submitted their completed questionnaires, asking them about their race.

Franz Sobotka, a Viennese music publisher owning several companies, was part of the list but his name was not deleted. Nonetheless in mid-May, the month in which Strecker was attending the premiere of his operetta, Sobotka fled Vienna with Hermine, his Jewish wife. He had heard that his family was at risk of imminent arrest by the Gestapo. They crossed the border to Czechoslovakia and reached the safety of Karlsbad (Karlovy Vary). Later Strecker will do away with the Sobotka’s refuge as a ‘health cure’.

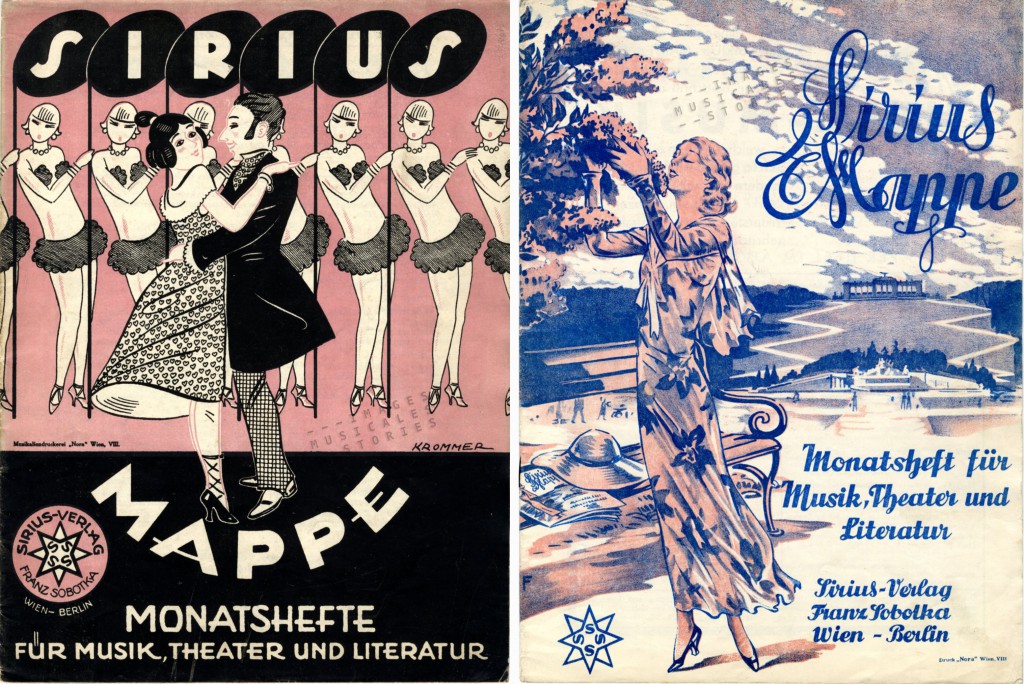

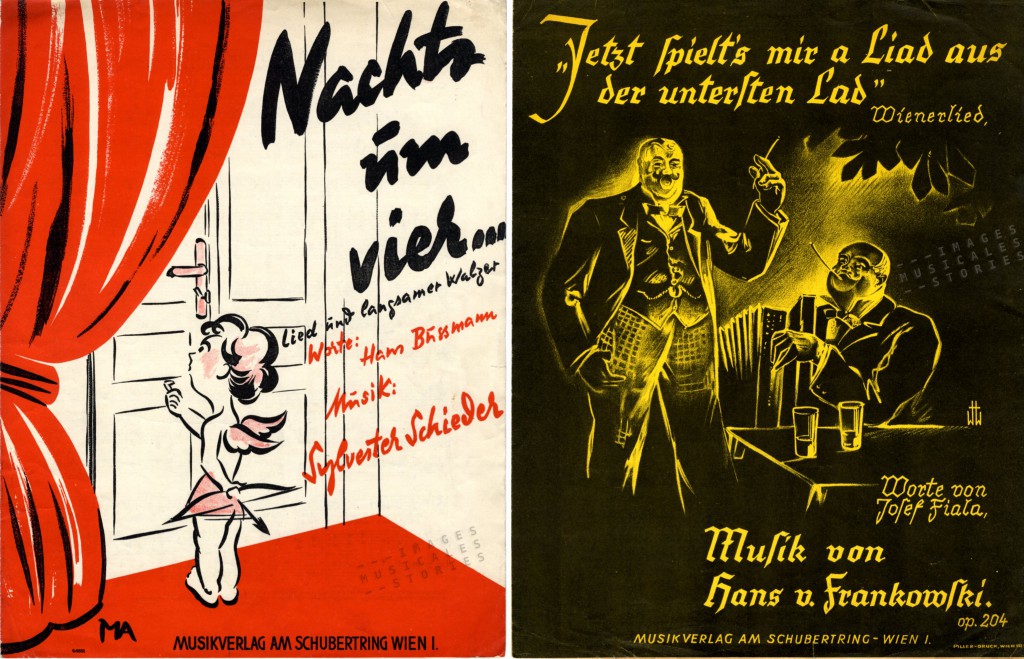

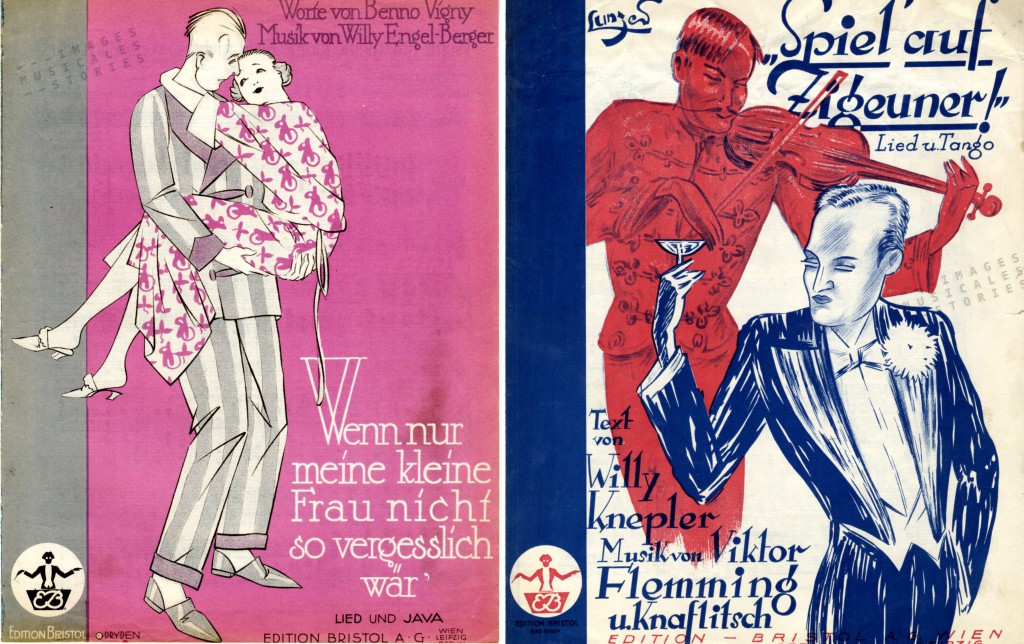

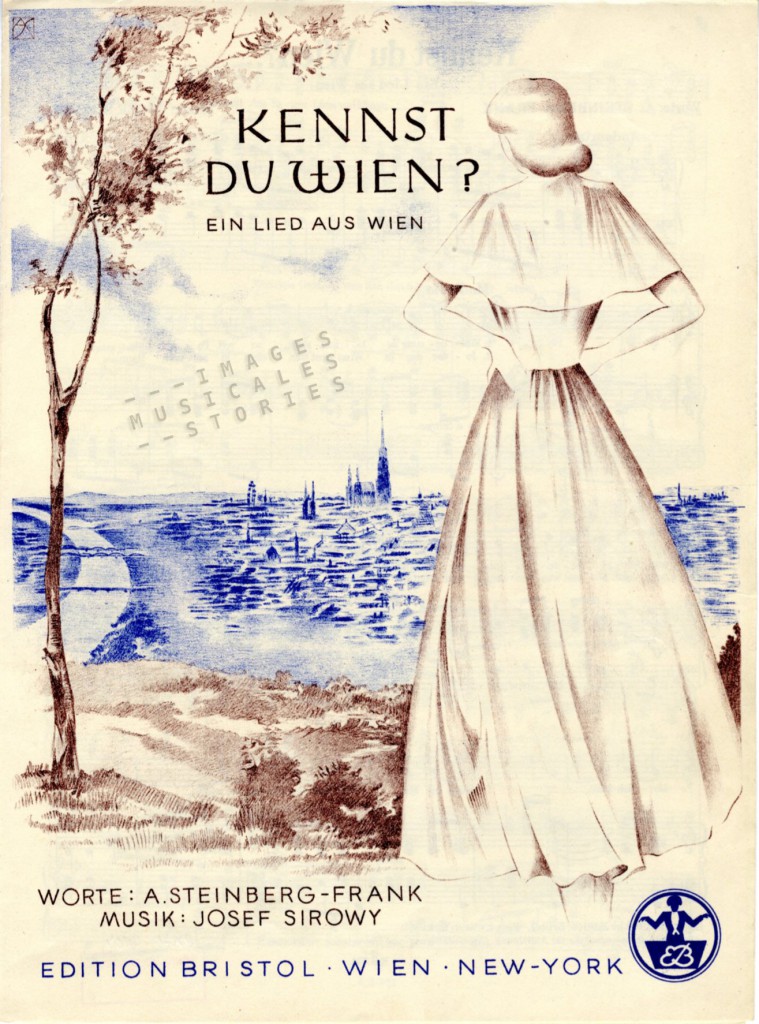

From Karlsbad, the family emigrated to New York. Sobotka’s car was confiscated and he was expropriated of a great deal of his assets. In 1939 Heinrich Strecker acquired the publishing companies (Bristol Verlag, Sirius and Europaton) which belonged to his ‘long-time friend’ Franz Sobotka for a paltry sum. At that time the companies had 18 employees and totalled a significant revenue. Strecker merged Sobotka’s companies together with his own to form the ‘Am Schubertring Verlag’.

While Sobotka was forced to rebuild his life in New York, Strecker was successfully performing in Austria, with many sold-out evenings. In 1942 he was able to buy a castle-like villa.

At the end of the war Strecker fled from Vienna. In 1946 he was accused of high treason for illegal activity, abusive enrichment and insult to the dignity of the librettist Alfred Steinberg-Frank. Streckers publishing house was placed in the custody of the American Property Control: Franz Sobotka, now a US citizen, reclaimed his properties and accused Strecker of taking over his editions under the guise of aryanisation. Aryanisation meant confiscation or forced sale far below the real value. The exchange of letters between Strecker, Sobotka and the American Property Control is made public by Fold3, an online collection of original US military records. The scanned, typewritten letters make a fascinating read.

Strecker’s defence is a litany of self-pity, presenting himself as a victim of the German ‘occupation’ and of unfortunate circumstances. Like so many other Austrians he refused to acknowledge that he had participated in the persecution of Jews. He denied ever being a member of the Nazi Party: it was his father, conveniently also called Heinrich, who had been a member. He himself ‘was persecuted by the Nazis’. Strecker enumerated his countless successes as a composer and blamed slander by jealous people for his present situation: “Viennese art was my goal, glory my companion, and I was envied by the yapping pack of incompetents as is often the case for successful artists.” In his defence Strecker recounts how in 1944 he got into trouble with a Nazi rival and subsequently his business was closed down. He also argues that he worked closely together with Jewish artists. Which is true: he created for example several songs together with Alfred Steinberg-Frank, who would later accuse him in 1946. Strecker also argues that Goebbels wanted to destroy the Wienerlied. Thus Strecker having been its “pioneer, front runner and king, he also had to fall”.

Strecker declared that after hearing about the aryanisation by Goebbels of several music publishers (Universal Edition, Josef Blaha Verlag, Figaro Verlag, Josef Weinberger Verlag and Friedrich Hofmeister Verlag) he wanted to save at least one Viennese publishing house, namely Bristol Verlag. The perfidious argument of Strecker was that he couldn’t be accused of aryanisation because Sobotka wasn’t a Jew, but an ‘Aryan’. Also part of his defence was his allegation that due to Sobotka’s manipulations he had bought an almost worthless business. Or in Streckers words: “by being so magnanimous I had suffered a terrible ordeal”.

Never in all the letters and accounts did Strecker show a hint of empathy with the Sobotka family who had been forced to flee and had been stripped of its possessions. He was ultimately convicted for high treason. Heinrich Strecker asked for clemency, and in 1950 after a few years of being ostracised, he was reintegrated and rehabilitated. For three decades he continued his work, public activity and lived in the Villa Strecker with his third wife Erika, who is 45 years his junior.

Austria gradually comes to terms with its Nazi past. In 2013 Austrian president Fisher said: “the crimes of Hitler’s Third Reich could not have taken place without the help of the ‘countless perpetrators, accomplices, informants and Aryanisers’ who worked as cogs in the Nazi machine”.

Further reading: Carla Shapreau