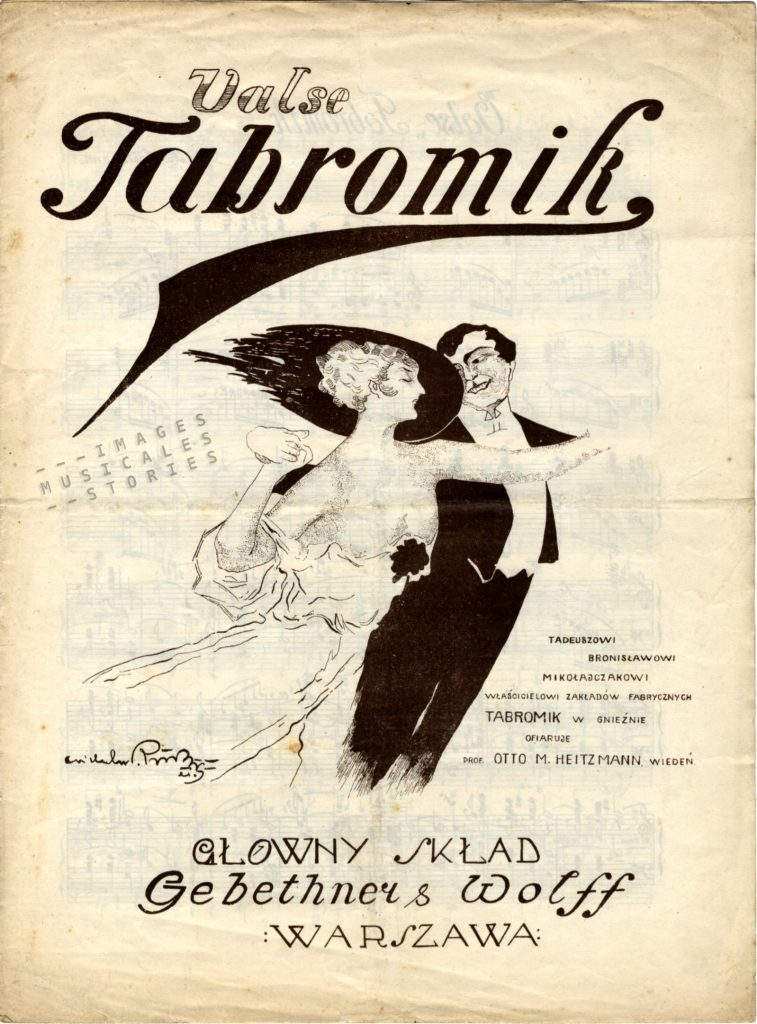

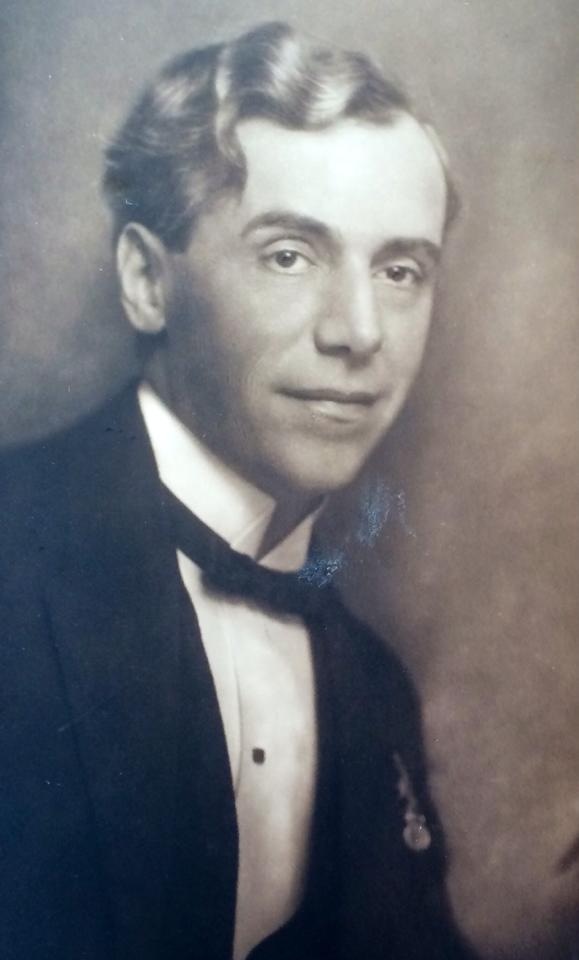

Alexandra Chava Seymann wrote us from Vienna about her grandfather, the composer of Valse Tabromik. Otto Heitzmann (1885-1955) was born in Linz, Austria. His parents continued the prestigious Viennese piano company founded by his grandfather Johann Heitzmann in 1839.

But as Alexandra Seymann tells us “Otto M. Heitzmann turned out to be more interested in actually creating and making music than in manufacturing pianos. He became a composer, conductor and music director. He worked in Poland, Denmark, Iceland, Austria, Germany, and the Czech Republic. He was married three times, first in Poland, then in Denmark (where he left two children), finally in Austria (where my mother was born). Unfortunately, due to his vagrant life, two world wars, and also family conflicts (his third wife was not exactly happy with his artist’s life and cut ties with him), there is close to nothing left of his portfolio.”

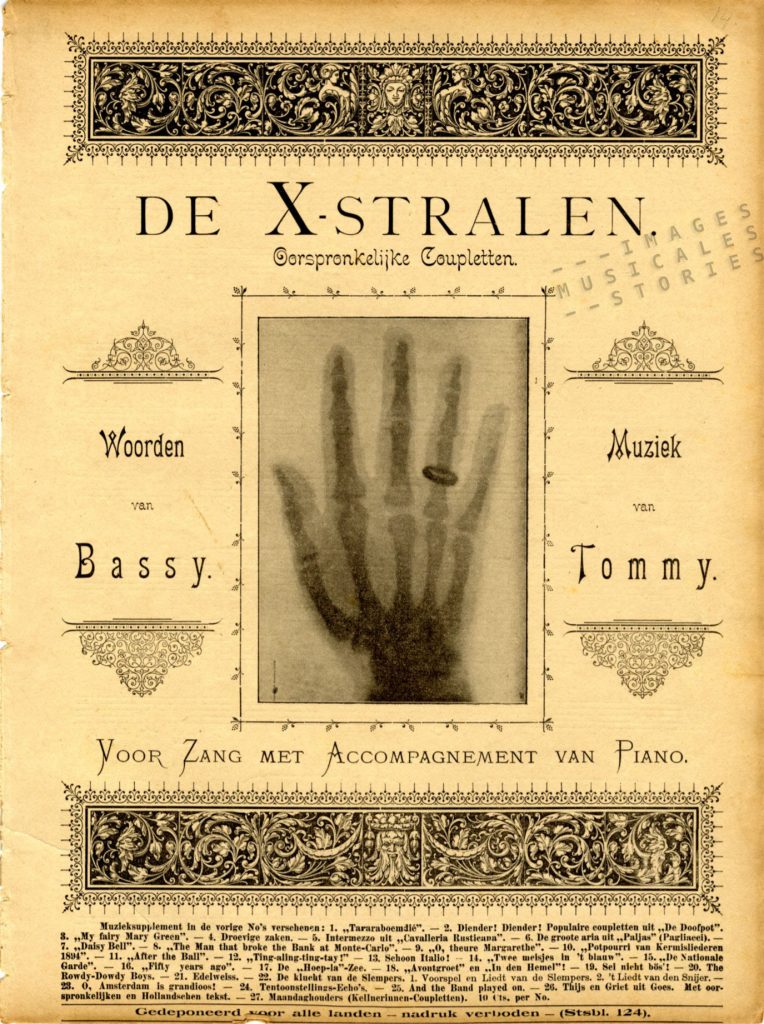

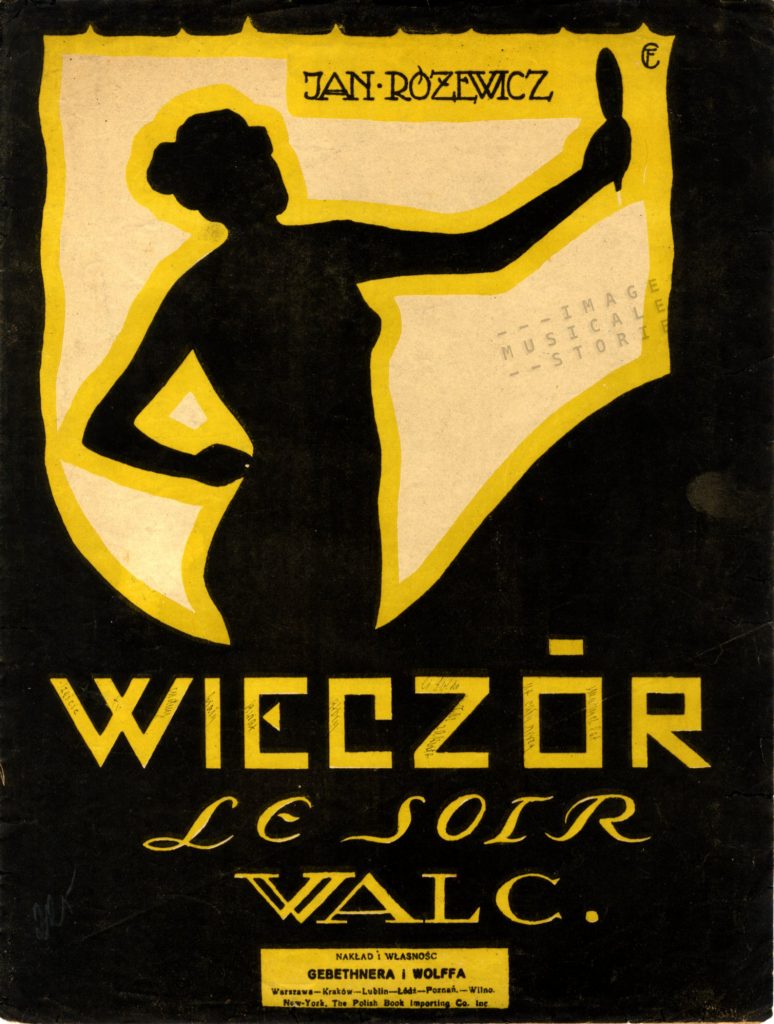

Otto Heitzmann composed the Tabromik walz while working in Poland in the early Twenties. The sheet music is used to promote Tabromik, a vodka and liquor factory in Poznán and Gniezno, Poland. The brand took its name from the first letters of the factory owner’s name, Tadeusz Bronislaw Mikołajczyk (1895-1933).

Mikołajczyk was an ambitious businessman who had only completed elementary school. He taught himself marketing and advertising and founded Tabromik in 1920. It is not clear where he got the funds for the company’s development but after a year it is said he already employed 250 people. He also started other successful projects but got involved in speculative and shady business and ended up bankrupt. Shortly thereafter, he died young as the result of an accident.

The illustration of the sheet music was created by Wilhelm Ludwik Rudy (1888-1940). The same year Rudy also designed a set of air mail stamps. They were issued by Aerotarg, the first Polish airline, in agreement with the Polish Post. Attached to each stamp was an advertising label, inscribed T.A.B.R.O.M.I.K. These stamps had to be bought for airmail in addition to the normal postage rate.

The short-lived Aerotarg was founded in Poznań in 1921 in order to serve visitors of the first Poznań Industrial trade fair. The organizers of the fair financed the venture. Aerotarg leased six Junkers F 13 aircrafts and the first regular Poznań-Warsaw and Poznan-Danzig flights were set up.

Between May and June the newly created airline transported around 100 passengers and 3 tons of parcels. The venture turned out to be unprofitable and ceased operation less than a month after its start-up. The fair committee lost its venture capital.

In the copyright statement of Valse Tabromik Mikołajczyk proudly mentions Tabromik’s ‘Publishing and Advertising Department‘, giving it a prestigious cachet . Compared to other Polish sheet music from the time though, it looks to us a rather clumsy publication. It is printed in black and white on thin, cheap paper with the notes shining through. The typography is uninspired. In an attempt to brighten up the cover Wilhelm Rudy drew a slightly bizarre couple: he grins idiotically at his waltzing partner while she —oblivious to her fraying hat— stiffly tries to ignore an upcoming nipple gate.

Apart from the few air stamps above, I could find almost nothing about the life and work of this illustrator, although there is the horrendous fact that Wilhelm Rudy died in the Katyn massacre in April 1940.

To conclude, Alexandra Seymann explains how so few things have remained from her grandfather’s musical opus: “Otto Heitzman died in 1955 in Waidhofen an der Thaya (Lower Austria), Austria, at the age of 70; my mother was merely 11 at the time, and I never got to know my grandfather as I was only born more than two decades later; the children from his second marriage died before I could get in touch with them. The Heitzmann family is now dispersed all over the globe, but there is very little information and very few documents left of Otto. I try to piece together whatever I can find in archives, old newspapers, official records. Finding a complete composition is a beautiful and touching moment!“