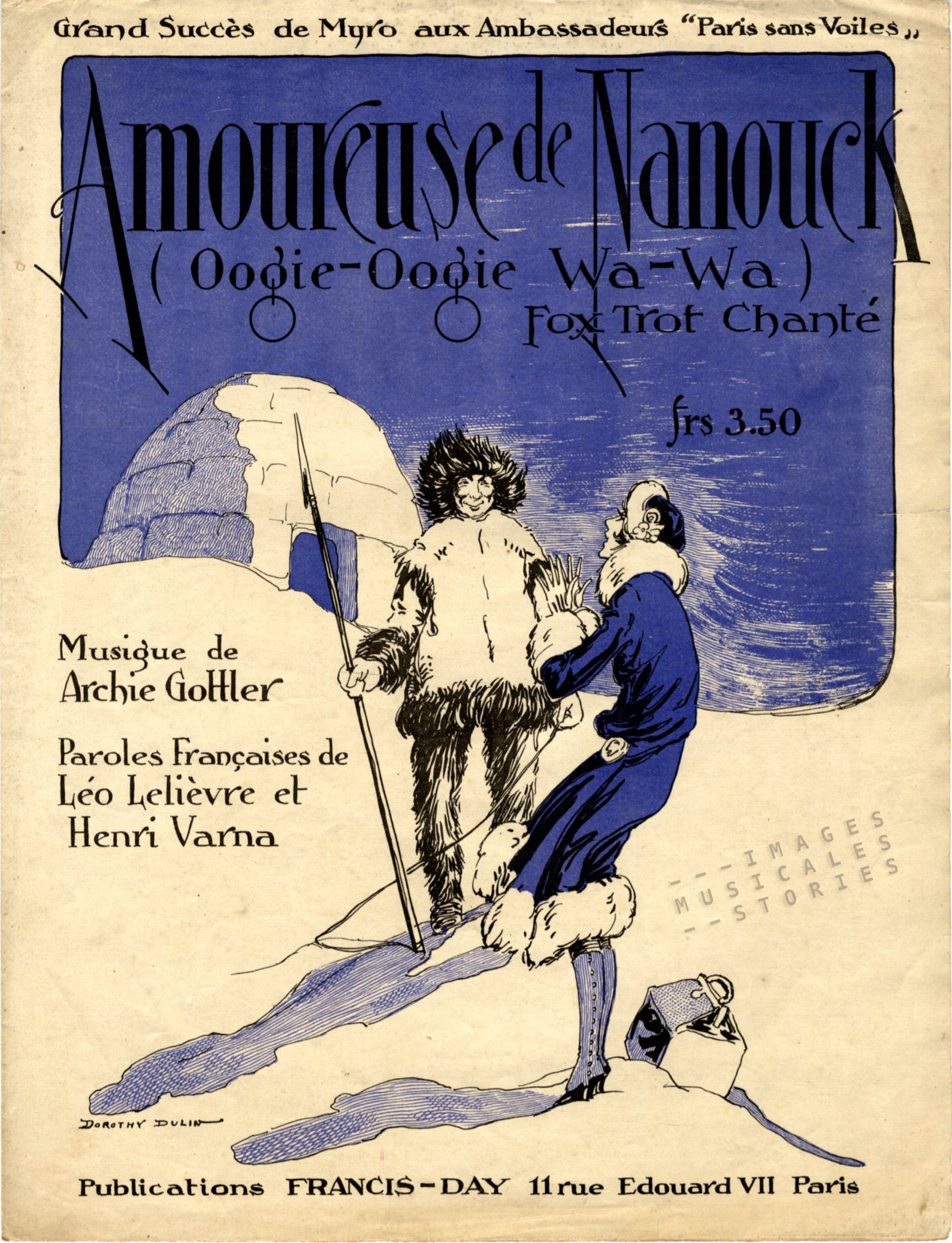

The Parisian flapper dressed in her fashionable fur-trimmed winter coat is obviously infatuated with Nanook, an Inuk hunter. We can imagine that she travelled so far up North to meet the subject of her fancy, after having seen him in a Paris cinema. Nanook of the North, a docudrama filmed by Robert Flaherty in 1922 was a world-wide sensation that prompted an ‘Eskimo craze’ in the Western world.

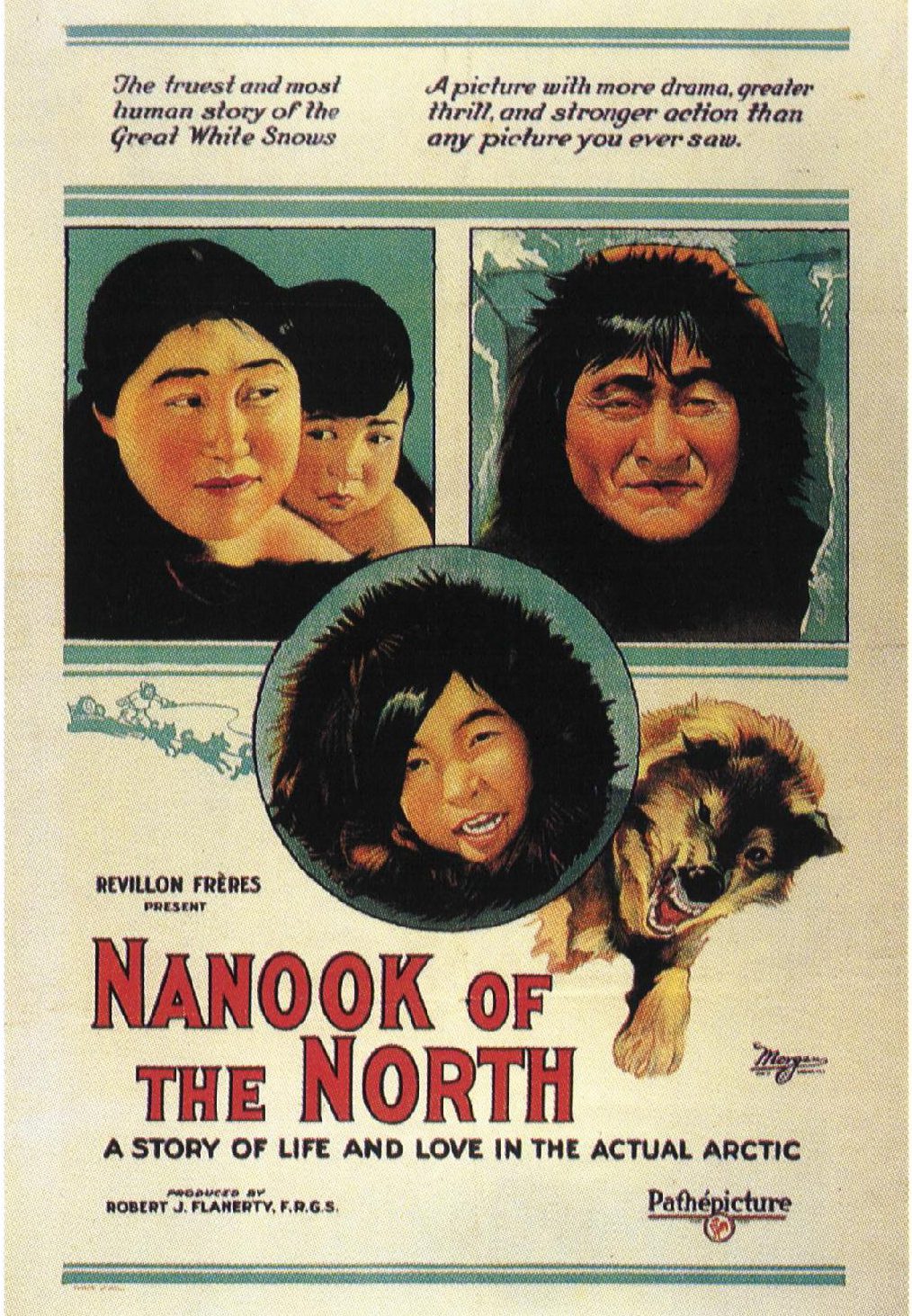

From 1910 Flaherty had made a few explorations to the North. At one moment he started shooting film of the Inuit life. In 1916 he had collected enough footage for a movie, but he lost almost all of it by dropping a cigarette onto the highly inflammable film. Flaherty returned to the North and this time concentrated on one Inuit family. His cinéma-vérité tour de force is considered a masterpiece even if most of it was staged. Nanook wasn’t the real name of the protagonist and his children were not his real children, nor were his wives his real wives. During the filming these ‘wives’ even became Flaherty’s mistresses. And with one of them he had a child that he later abandoned.

Since it would have been impossible to film inside the dark interior of an igloo, a special set was built consisting of half an igloo. The film was meant to give impressions from the far north of the Polar Regions. In reality Flaherty‘s shots conveniently came from the north-eastern part of Hudson Bay. But at that time there were no rules for filming a documentary.

Nanook of the North was a kind of advertising film distributed by Pathé. It was financed by the Parisian fur traders Revillon Frères. They were the largest fur company in France with branches in London, New York and Montréal, and 125 fur trading posts. Nanook of the North was filmed near one of their trading posts at Inukjuak, Quebec.

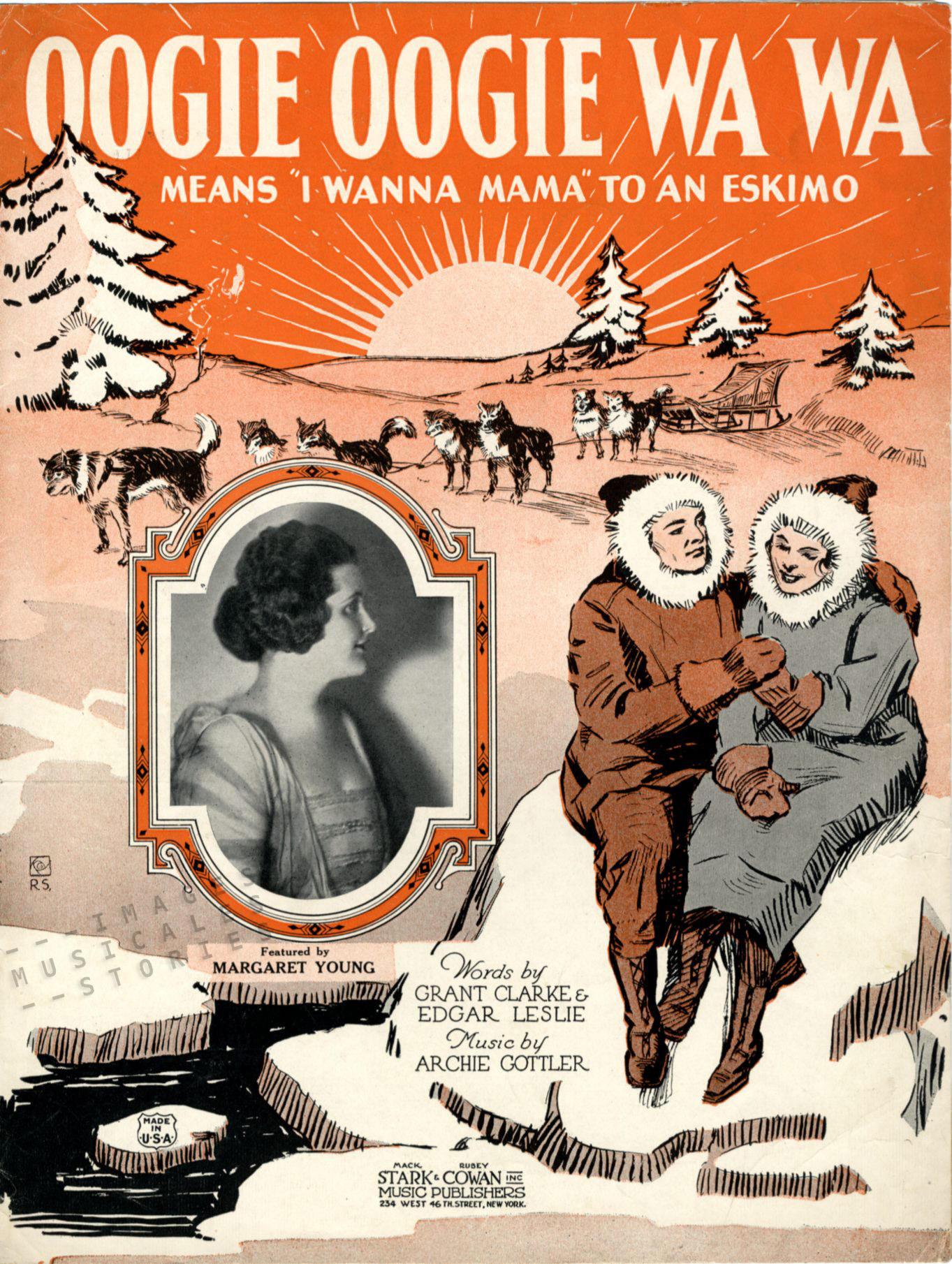

After the release of the film, Margaret Young introduced the humorous song Oogie Oogie Wa Wa in vaudeville, a song with the usual double entendre. Quickly the song became one of the popular tunes of the day and was translated in French as Amoureuse de Nanouck. It was one of Al Jolson’s greatest hits. At one point it was banned from being played at local music pavilions until it had been analysed by the Morals Committee.

Girls like simple things,

Beads and ten cent rings,

They kiss you for a chocolate drop,

Imagine if a fellow had a candy shop…

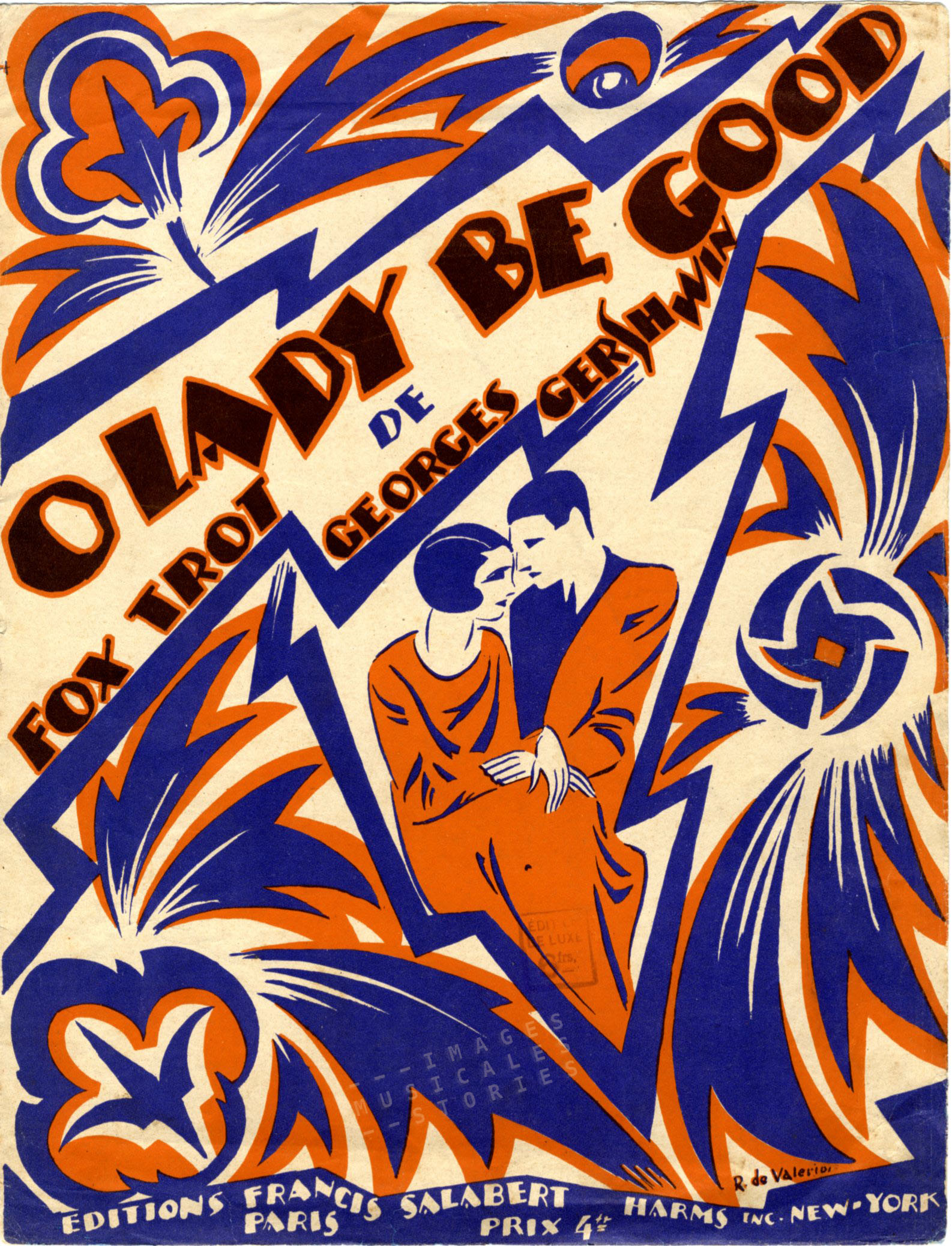

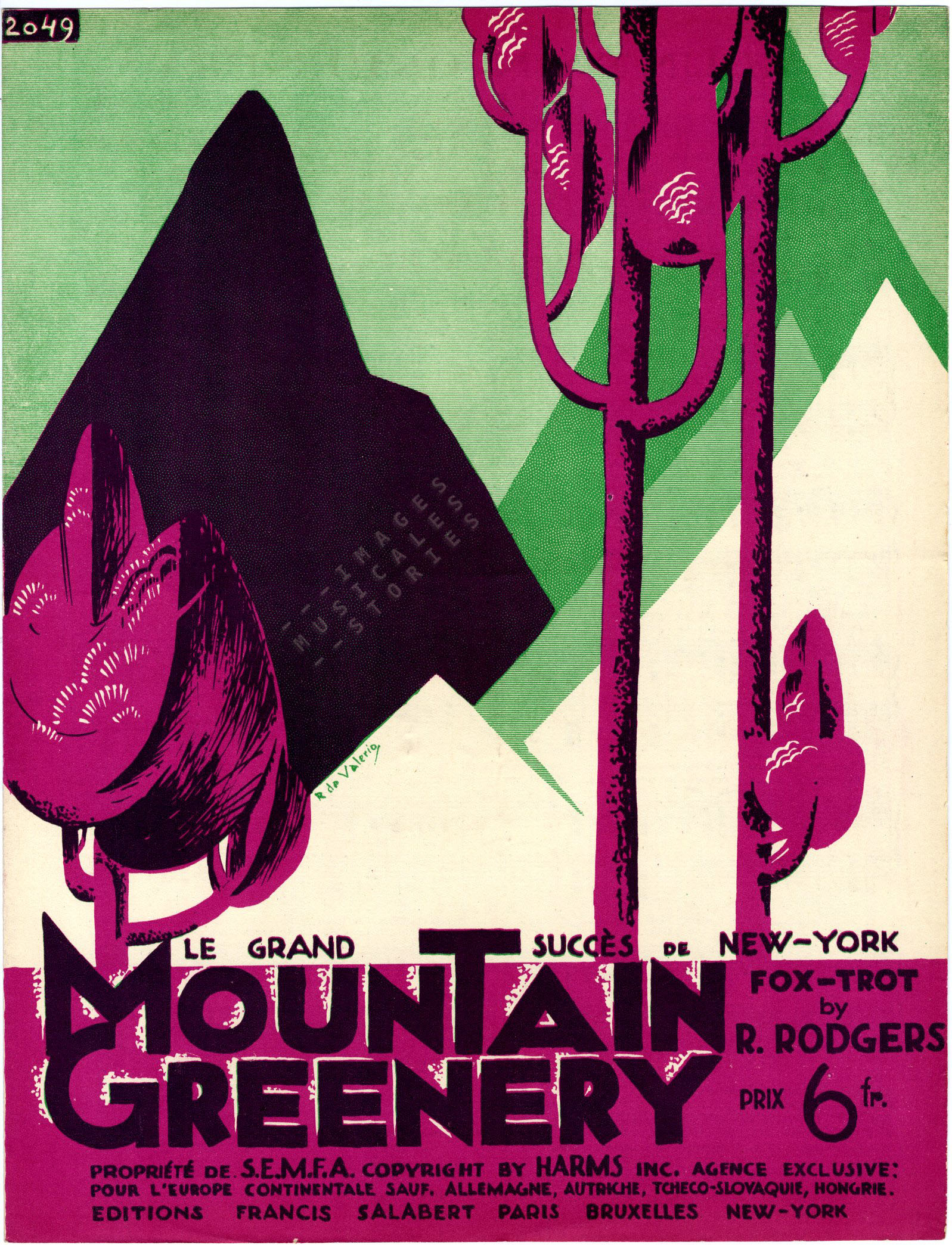

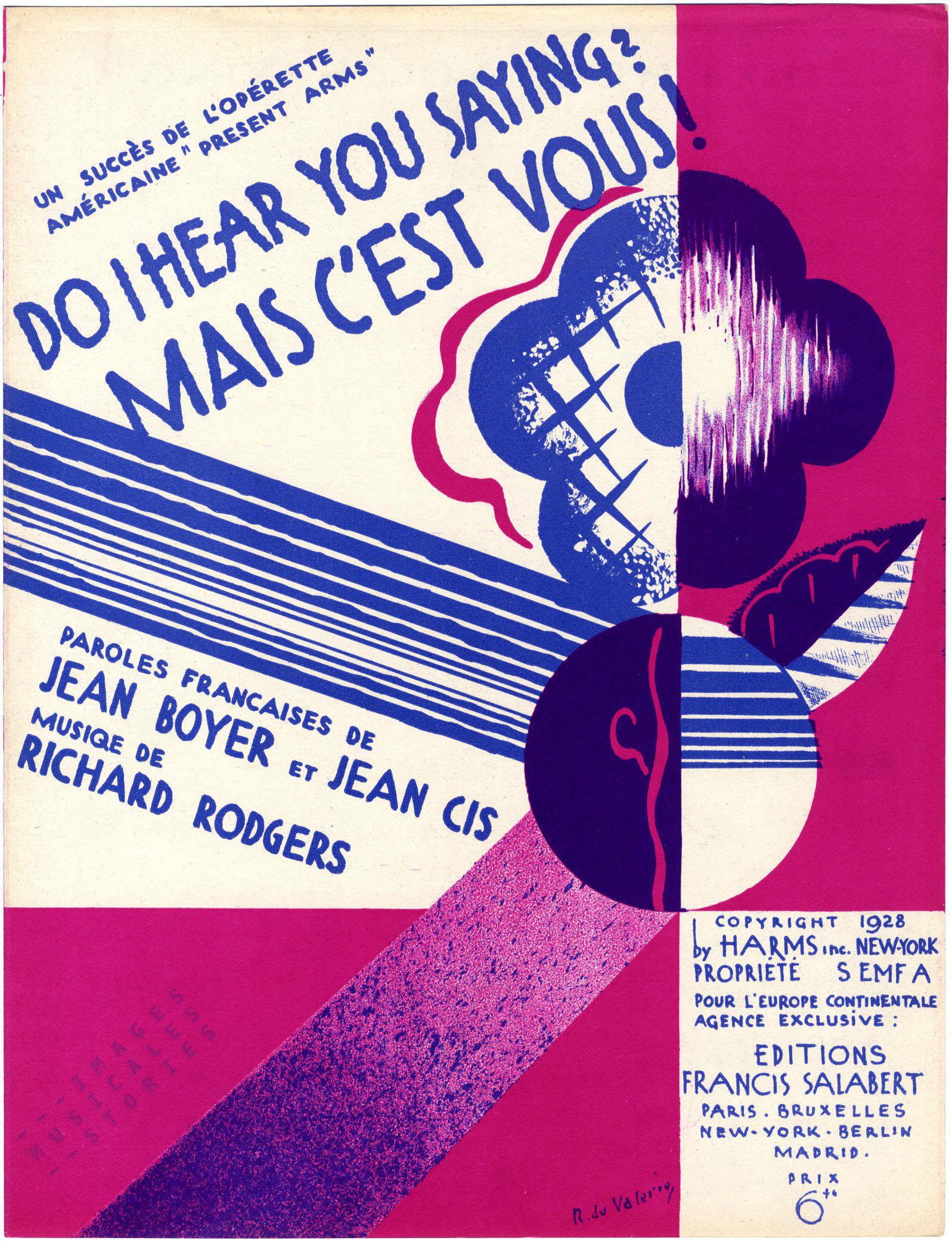

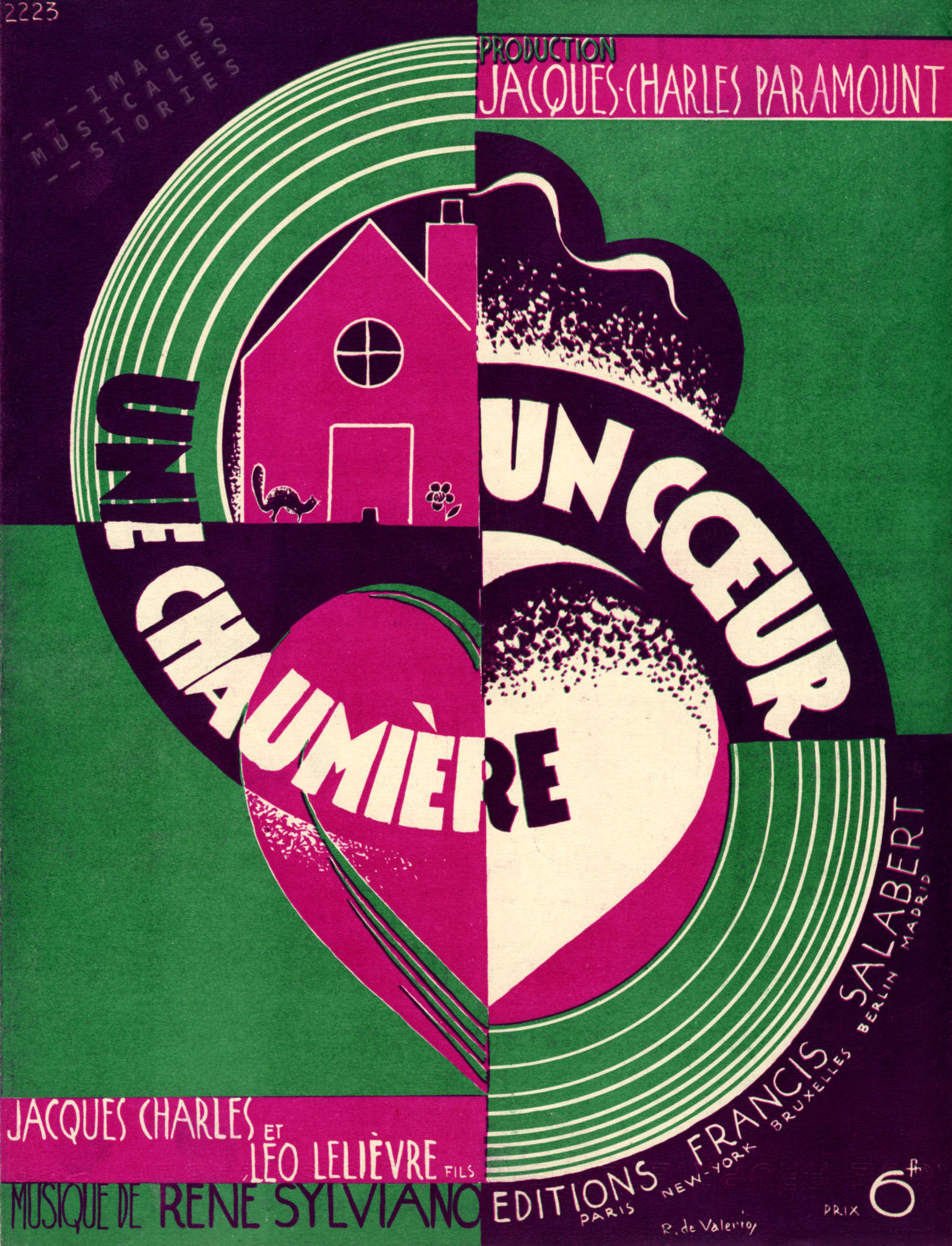

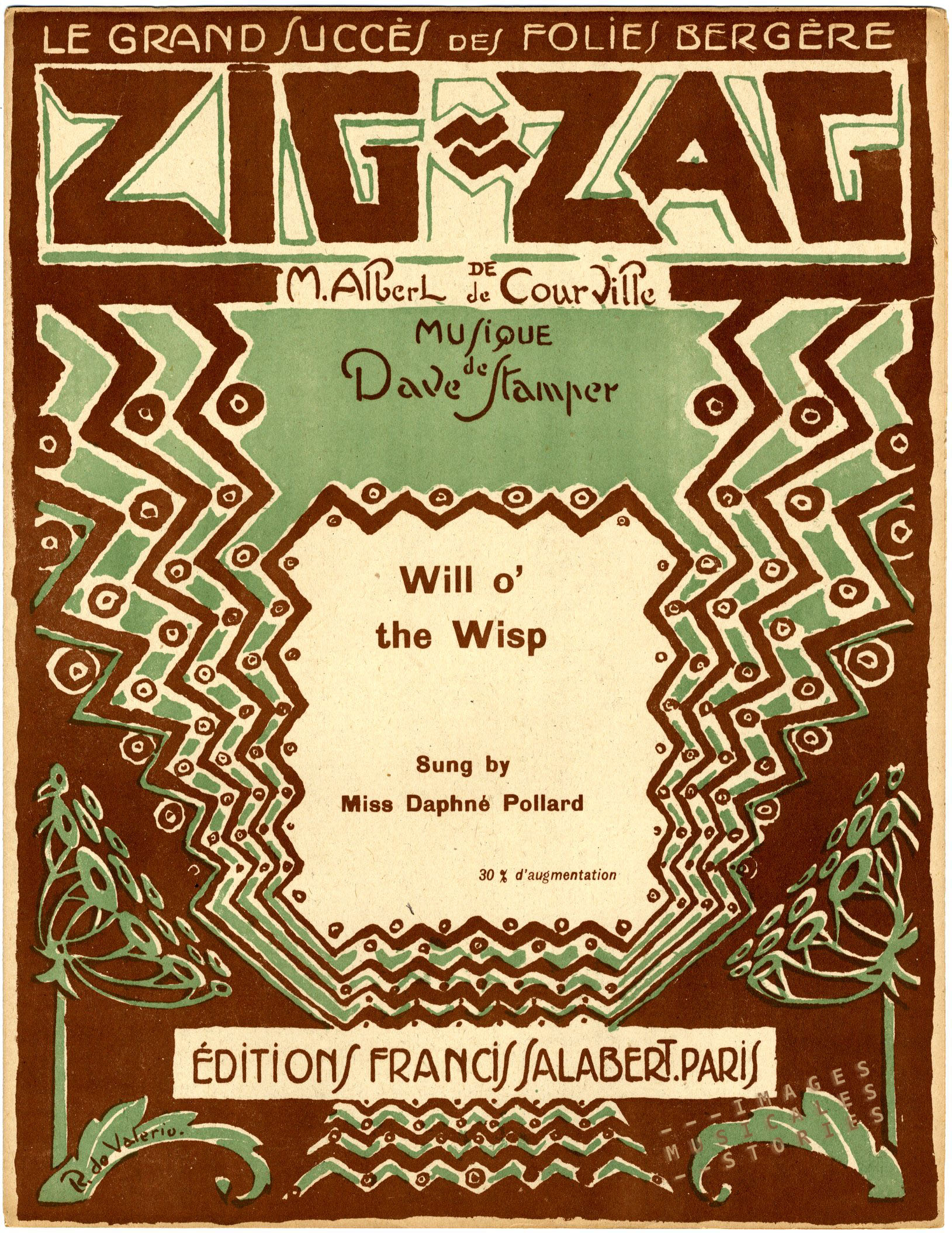

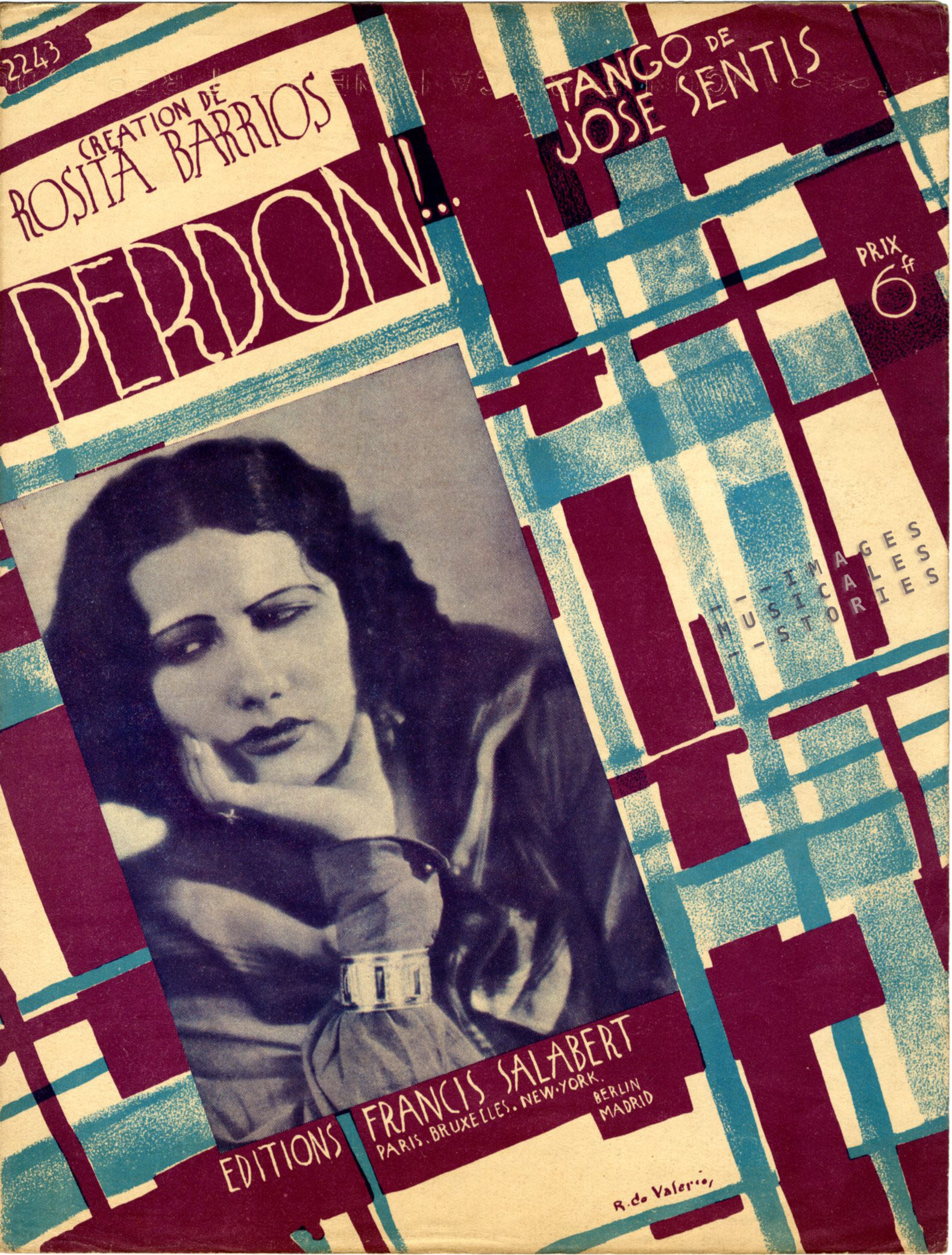

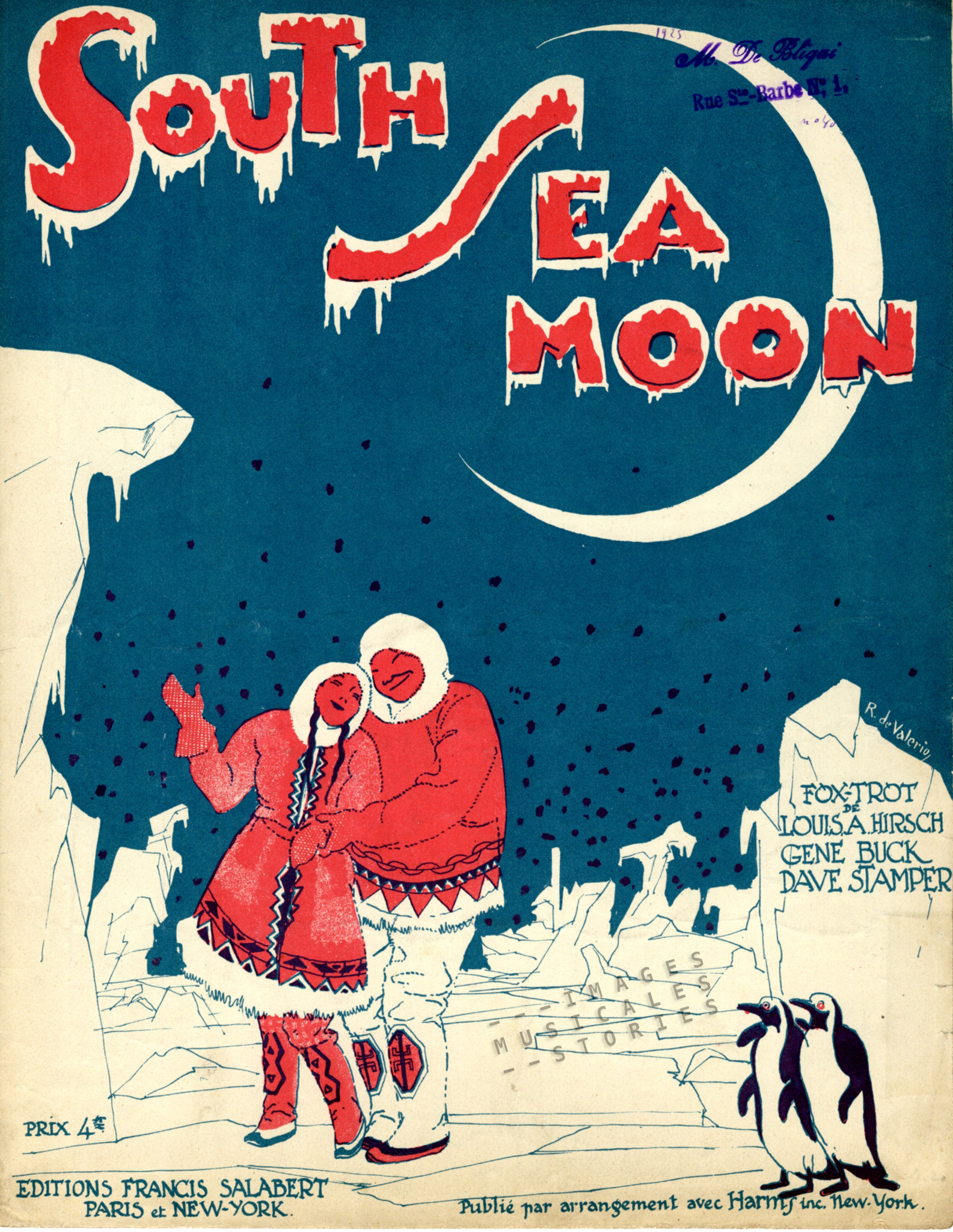

Around the same time, Salabert published the song South Sea Moon. I don’t know what got into Roger de Valerio when he illustrated the cover for this song with a couple of Inuit resembling Nanook and one of his ‘wives’. One normally associates the South Sea with tropical Islands and blue lagoons.

Maybe he confused it with the Southern Ocean? But then again, in his drawing de Valerio combined penguins (living in the Antarctic region) with the happy-looking Inuit couple (living in the Arctic).

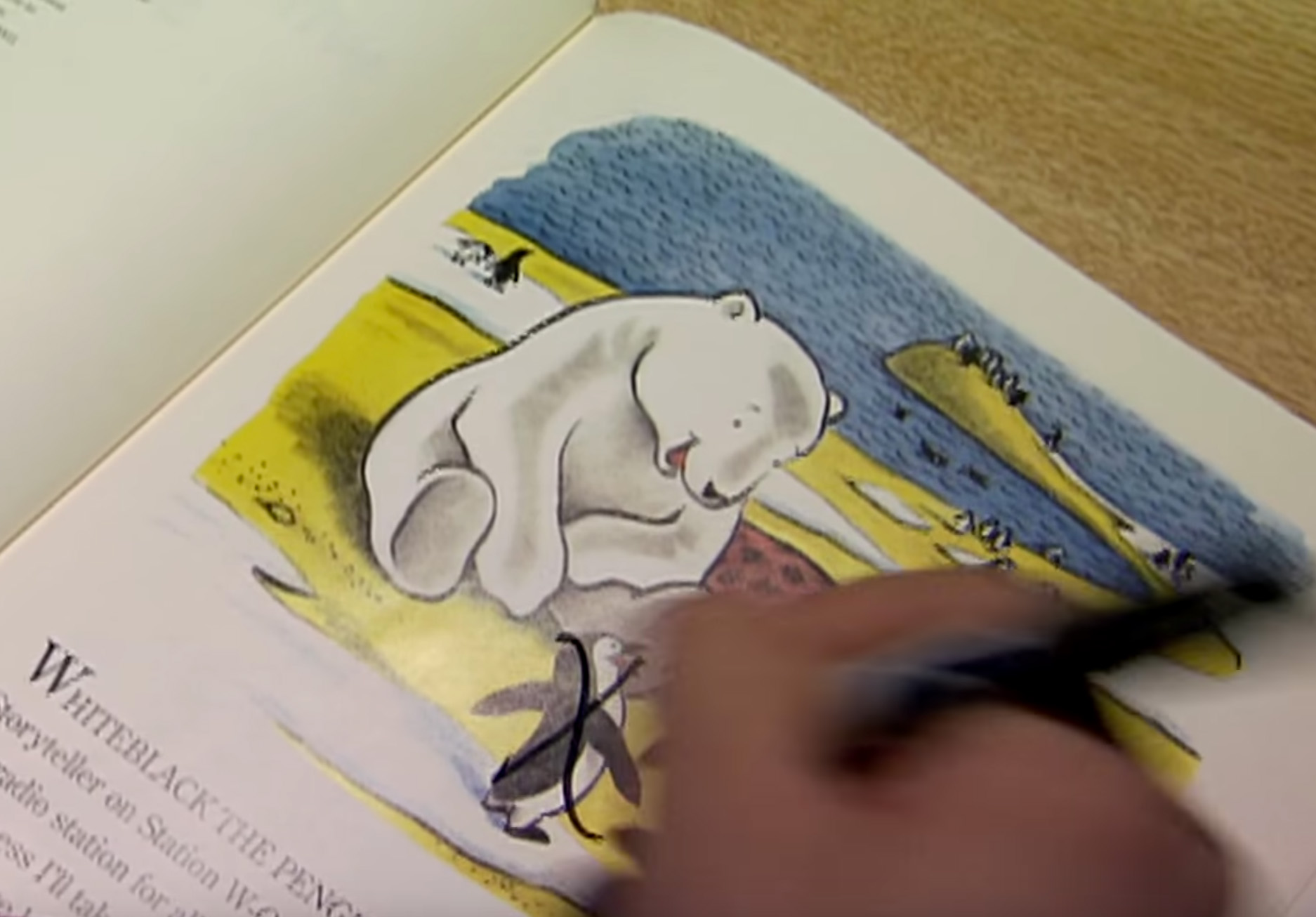

In the mockumentary ‘Qallunaat: Why White People are Funny’ a man from the Book Correction Division is crossing out with a marker all the penguins in drawings where they are pictured together with polar bears. The film is written from the Inuit perspective on the oddities of Qallunaat, the Inuit word for white people.

Quite Humoreskimo!

I have to end this post with one of my favourite songs from the seventies: Don’t Eat the Yellow Snow by Frank Zappa, about a man who dreams that he was an Eskimo named Nanook.

And my momma cried:

Boo-a-hoo hoo-ooo

And my momma cried:

Nanook-a, no no (no no . . . )

Nanook-a, no no (no no . . . )

Don’t be a naughty Eskimo-wo-oh

(Bop-bop ta-da-da bop-bop Ta-da-da)

…

An’ she said

(Bop-bop ta-da-da bop . . . )

With a tear in her eye:

Watch out where the huskies go

An’ don’t you eat that yellow snow