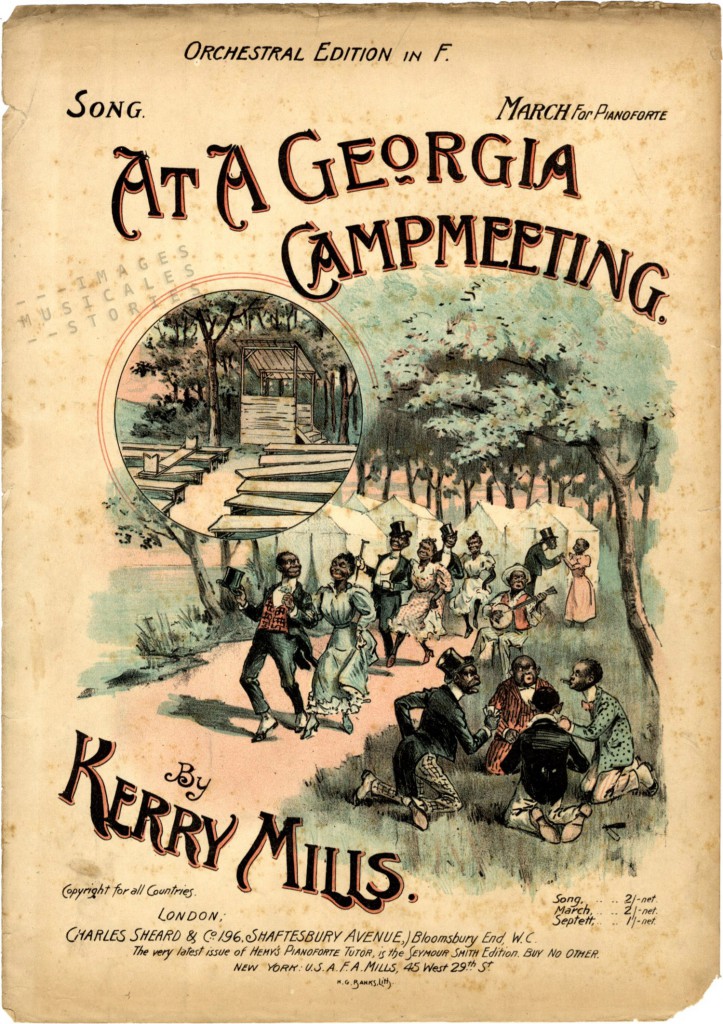

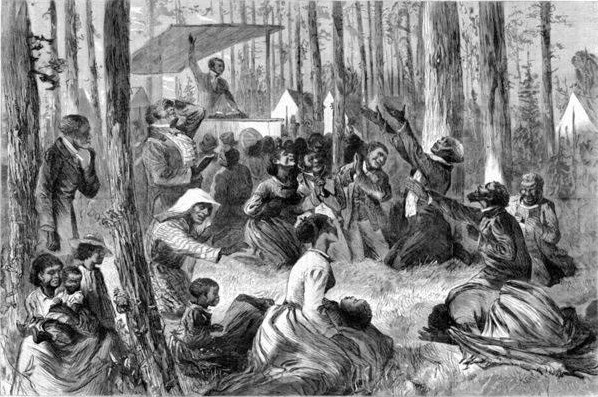

Though the term ‘camp meeting’ might be common knowledge for Americans we are not familiar with it. We tried to infer its meaning from the above English cover illustration by Banks. We see African Americans in a pastoral scene. Three couples are dancing a cakewalk accompanied by a banjo player. In the background a man is trying his luck with a girl. A front scene shows four card players in an animated game. The agitation of the man in his top hat is perhaps related to the razor lying nearby. Was it used by a cheater to mark the cards? Or is it the racist stereotype to symbolise the menace of violence in this idyllic spot? In the distance is an encampment: we see tents, wooden benches and the shelter or arbour as if for a leader or speaker. From this late 18th-century image we can suppose that a camp meeting was a festive gathering. The black community apparently met there, had fun and spent the night in the woods, right?

The Frenchman Léonce Burret gives us his interpretation of a Georgian camp meeting: he draws a cartoonish African-American wedding. The couple, smartly dressed, is dancing a cakewalk accompanied by an accordion player. Mhmmm could a camp meeting have something to do with weddings among black citizens? In this cover it was certainly represented in a condescending, European way. Or didn’t Léonce Burret have a clue as well?

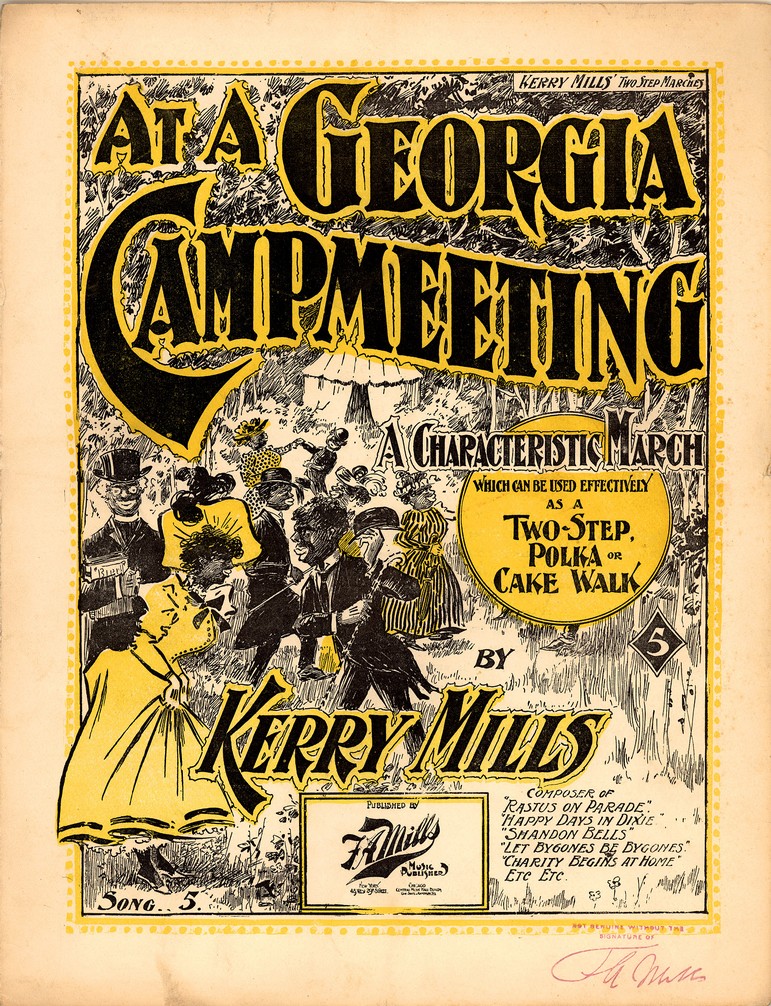

Time to bring in the American original sheet music published by the composer Frederick Allen ‘Kerry’ Mills himself. Again we see a merry gathering of African Americans enjoying a cakewalk, and we also view a tent in the background. But this time, on the far left there is a preacher holding a bible. We get another clue from Kerry Mills’ foreword to his cakewalk, telling us that his march was not intended as part of a religious exercise.

All right, finally a camp meeting is something spiritual, a religious meeting held in the open air or in a tent‘ according to the Oxford Dictionaries.

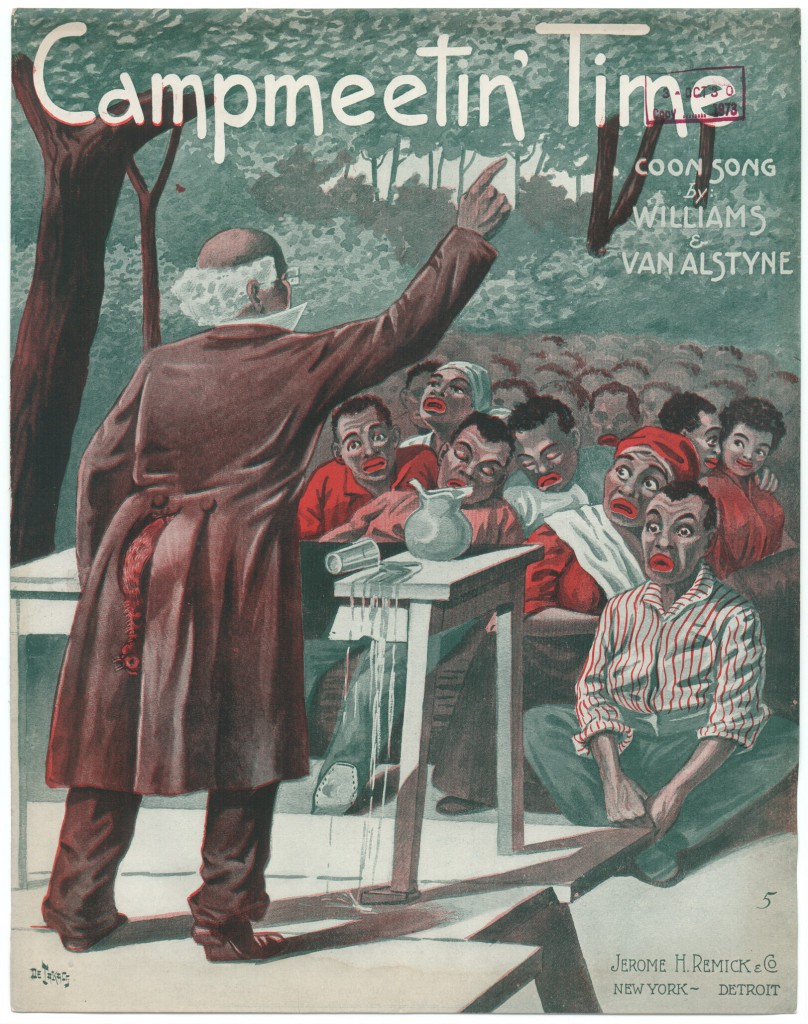

The religious significance of a camp meeting, is confirmed by American illustrator André de Takacs in the above sheet music. A cleric is preaching so fiercely that he upsets his glass of water. The death chicken hidden behind the preachers coat is another early 20th century racist stereotype, associating stealing chickens with black people. Four worshippers consider the terrors of hell while a young couple imagines the glories of heaven.

We searched for the history of ‘camp meetings’. The spiritual practice seems to have its origin in the Second Great Awakening, an evangelical movement promoted by protestant preachers in the early 19th century in America. Originally camp meetings were held in sparsely populated frontier areas without churches and full-time ministers. So the solitary settlers would travel to a particular camping site. There they could listen to itinerant preachers, pray and sing hymns non stop for an entire week. Maybe due to exhaustion from the ceaseless services, some participants lost control of their emotions. Sinners would fall on the ground amid shrieks and cries for mercy (the falling exercise), shake their limbs and head violently (the jerks) or roll over the floor uncontrollably (the rolling exercise).

But a camp meeting was also a welcome reprieve for the farmers who had lonely and difficult lives. It was an opportunity to reunite with family and friends. And aside from spiritual support, a camp meeting also offered singing, music playing, and dances.

Camp meetings stayed popular with rural Americans around the Bible Belt. According to the New Georgia Encyclopedia camp meetings were so popular in Georgia by the 1890s that the phrase ‘at a Georgia camp meeting’ became a common expression. Early on, camp meetings also attracted many African Americans. They came together with white people, staying in segregated quarters or went to their own camp meetings.

Today revival camp meetings are still used to reinvigorate churches.

In 1904 the modernist American composer Charles Ives (1874-1954) gave his nostalgic Third Symphony the subtitle ‘The Camp Meeting’. He remembered the evangelical revival services from his childhood, and he used the hymn tunes as basic material for this composition. Ives’ music was considered radical for its day and it was largely ignored during his life (the symphony premiered not until 1946). Even today, his music isn’t frequently programmed either and that is a pity. Listen for yourself: here is the first movement, Old Folks Gatherin’. Spiritual power, full force!

Het afstotende van deze Amerikaanse bladmuziek is dat men de Afro Amerikanen altijd afbeeld als domme mensen met enorm dikke lippen. zeer discriminerend en ik zal deze bladmuziek dan ook nooit aanschaffen. Dat jullie dat wel doen,vanwege de historie van bladmuziek dat begrijp ik volstrekt.

Je hebt volkomen gelijk Bram. We laten dan ook niet na om te benadrukken in onze posts dat het racistische en stereotype afbeeldingen zijn.