Nénette and Rintintin were tiny yarn dolls that took Paris by storm in 1918. Parisian ladies would pin them on their bodice as mascots to protect them from the bombs and shells. Men hung the two small talismans on their watch chain and soldiers would keep them in their knapsack. As is often the case with fetishes, the superstition was conditional: it would ward off danger only if the charming little dolls had been given, exchanged or received, but not purchased.

Guillaume Apollinaire described the Nénette and Rintintin craze in august 1918: “Talismans and amulets have always existed and will always exist. Nénette and Rintintin are a helpful kind of deities in whom the midinettes have put their trust since the beginning of the war; but the cult became widespread only recently, since circumstances have been favourable to its development. It is perhaps the first time that, since Ariadne’s thread, man has put his trust in a few strands of wool, thread or silk. … Nénette and Rintintin are the first gods born in the 20th century.”

The craze in Paris did not last long (after about three months the frenzy was largely over), but the popularity of Nénette and Rintintin knew no borders.

The inspiration for the mascots were two dolls made by the illustrator Poulbot. Francisque Poulbot was famous for his drawings of the street kids of Montmartre. In 1913 he also designed two porcelain dolls, called Nénette and Rintintin as a Christmas novelty for the Magasins du Louvre.

Only a few of these dolls in porcelain were produced. The boy was called Nénette, which is a female nickname, but it was what Poulbot’s wife lovingly called him — he in turn called her Rintintin. At the start of 1914 the catalogues of the large Parisian department stores featured these dolls. At that time, most of the toys and dolls on the market in France were of German manufacturing. Poulbot argued that these had ‘silly looks and oakum wigs‘ and with his two little dolls he wanted to offer a French, more realistic alternative.

It wasn’t a big commercial succes: Poulbot’s dolls were only on the market for a year and the production was halted during the war. But the names of the dolls outlived their commercial failure, and were generously given to the home-made woollen figurines. Albeit the names of the boy and girl were switched.

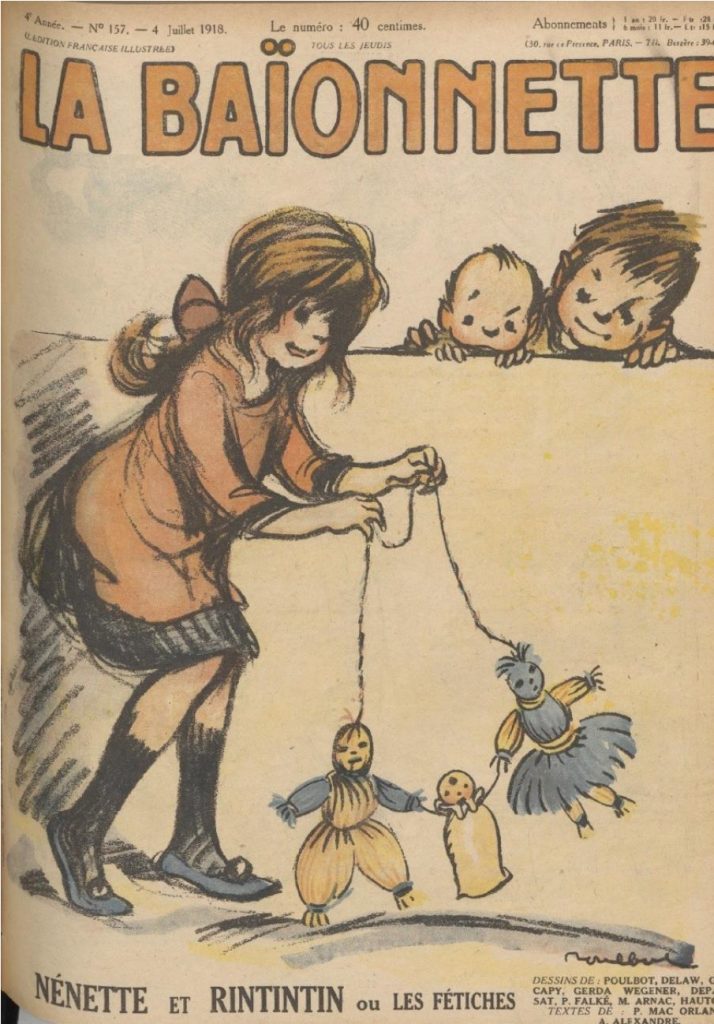

The craze in the spring and summer of 1918 took all forms: cheap woollen dolls were sold in haberdashery shops, lockets and small jewels were designed around the two heroes, and of course they covered the pages of many newspapers and magazines. There were also numerous postcard series published with the adventures of the mascots.

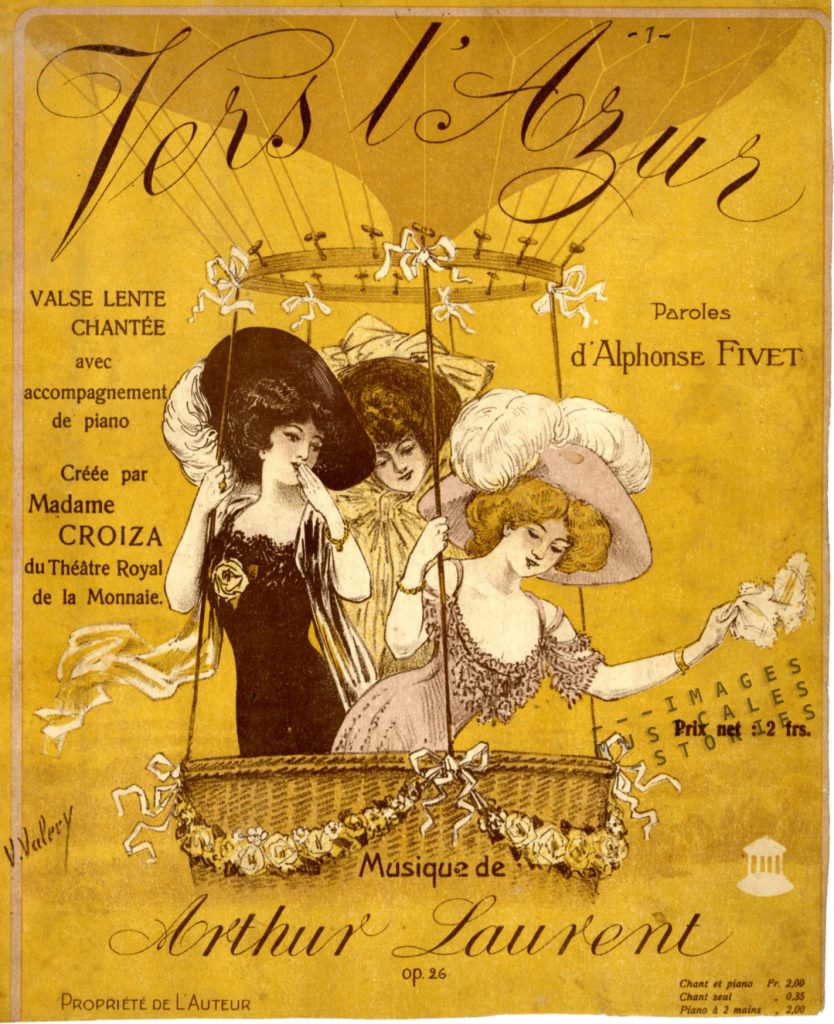

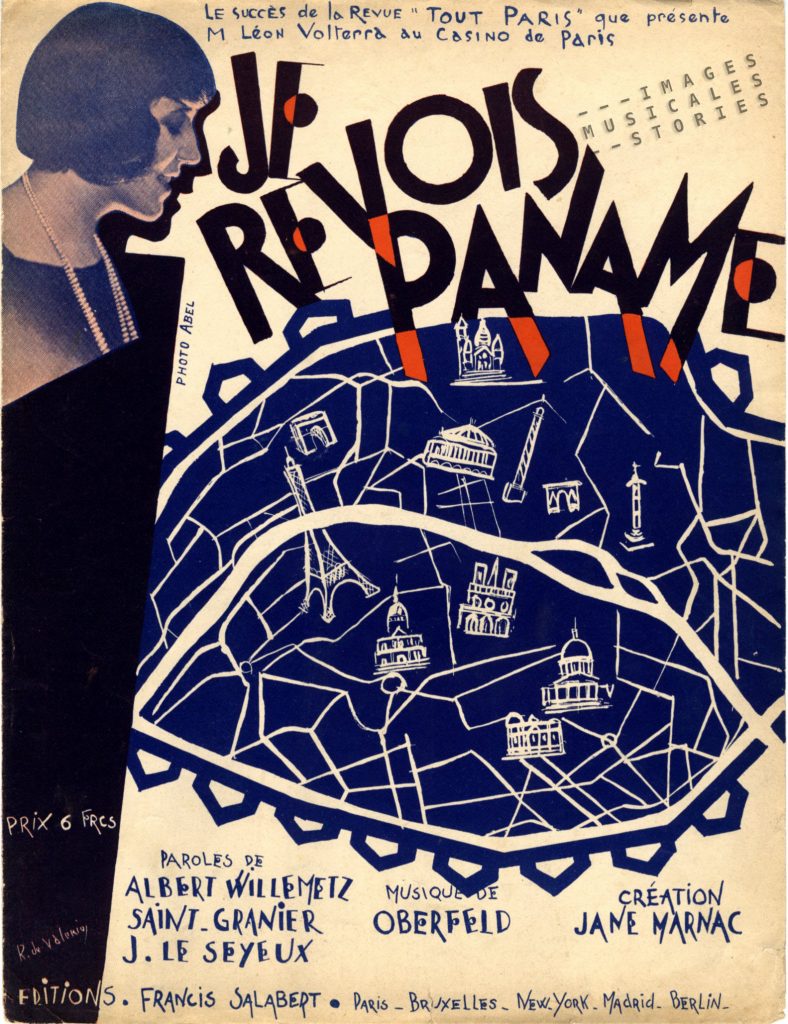

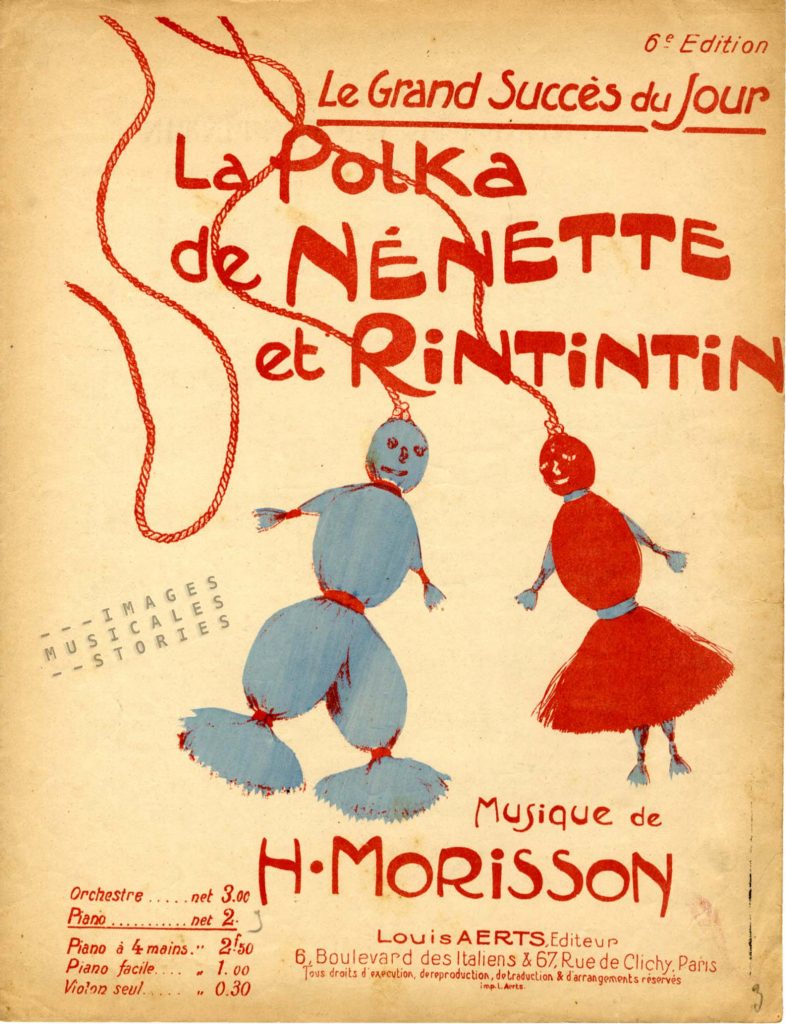

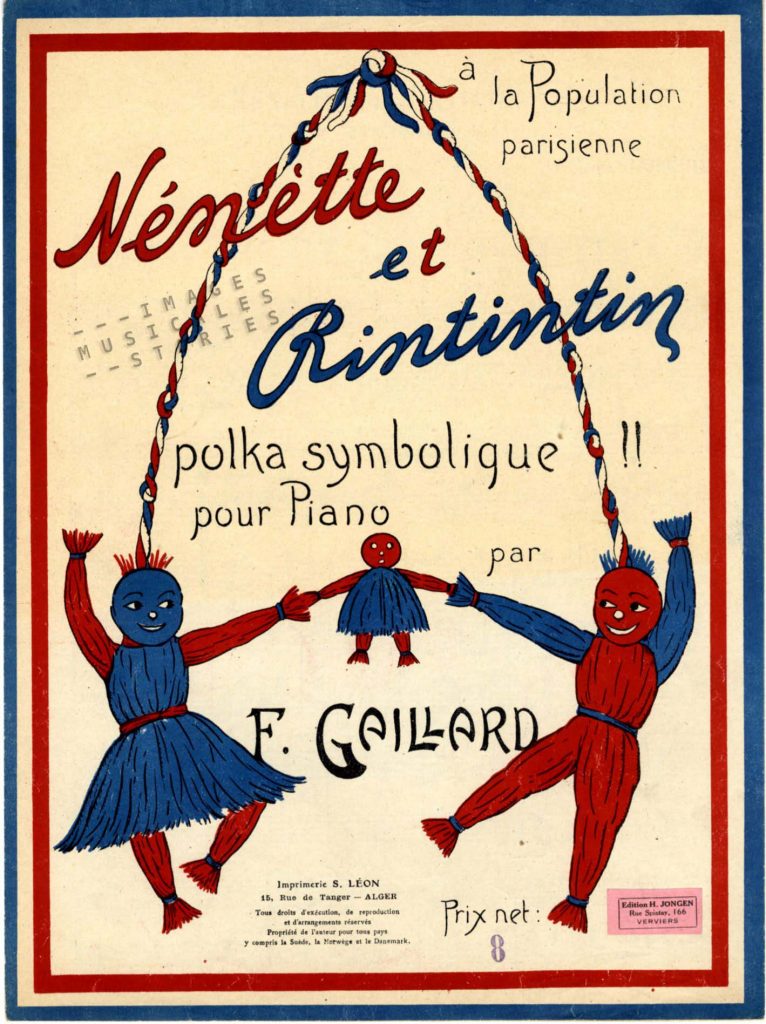

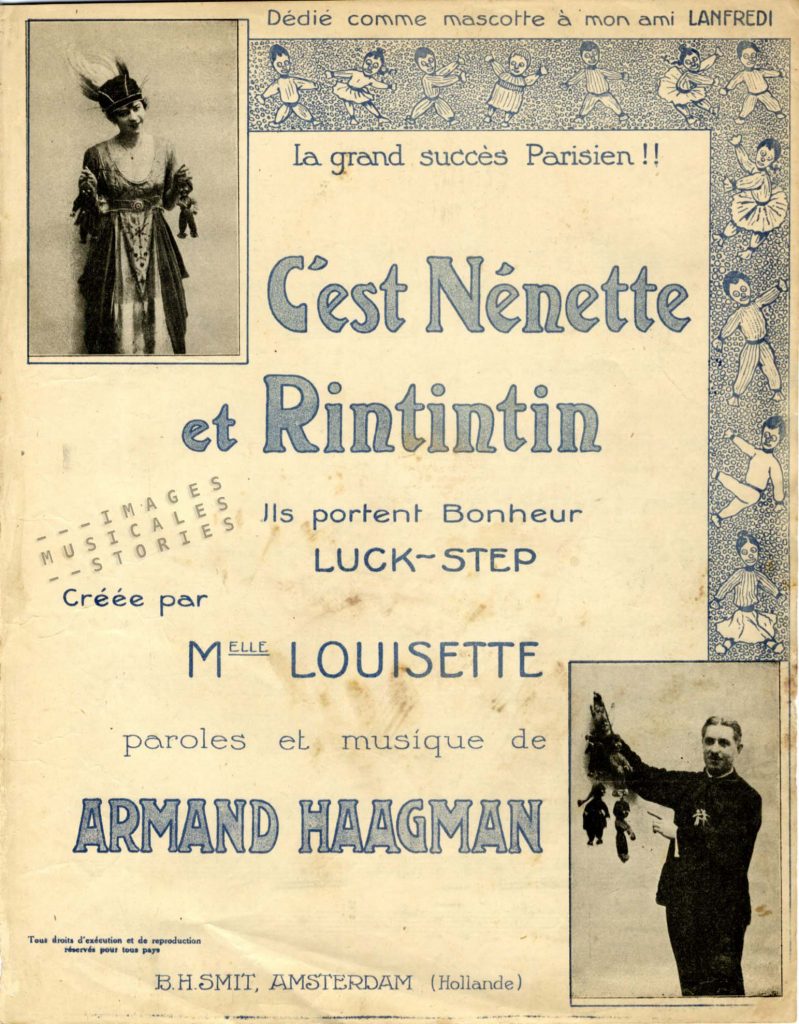

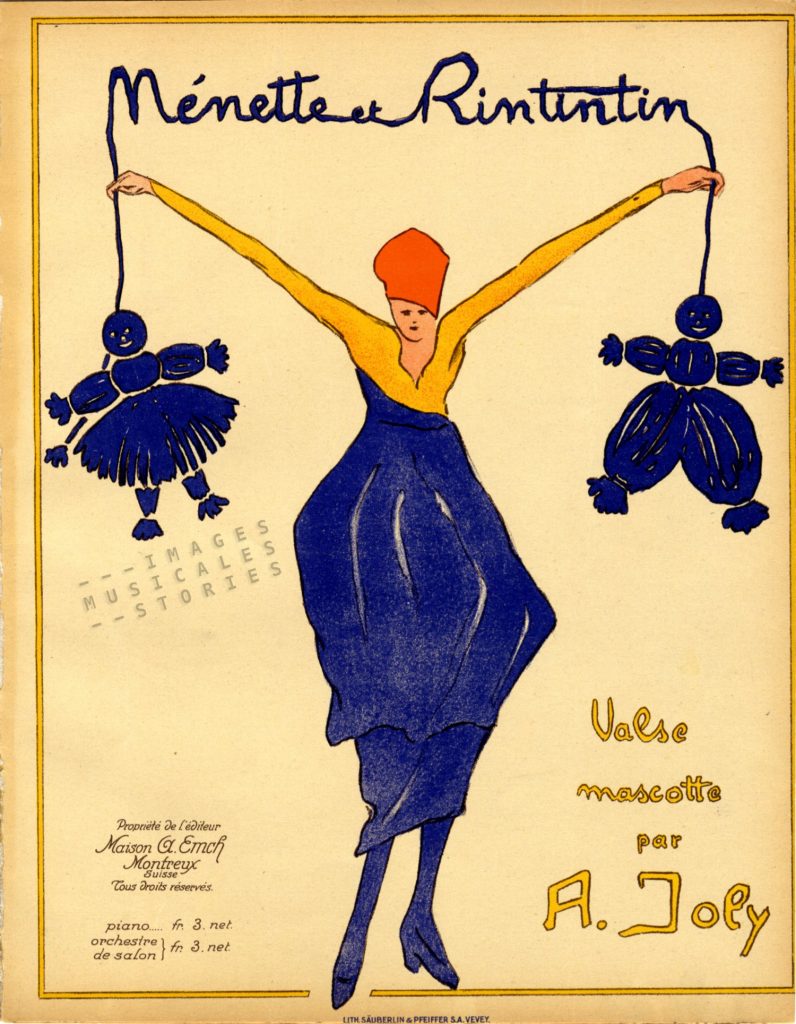

As you would expect, Nénette and Rintintin also have set foot in our sheet music collection. It is proof of their popularity that songs were written about them and tunes composed in their honour. Not only in France, but also in Algeria…

in The Netherlands…

and in Switzerland.

To conclude this lucky post, we found a very short British Pathé news reel buried in the myriads of Youtube films. A souvenir of the once internationally renowned Nénette et Rintintin…