This drawing of a crucified owl illustrates a gruesome tradition. Not so long ago it was still practised in rural France. With a wingspan of nearly one meter and its nightly eerie shrieks (listen for yourself), the barn owl was thought to be a bad omen. To keep evil at bay superstitious farmers used to trap the bird and nail it, sometimes still alive, above their barn’s door.

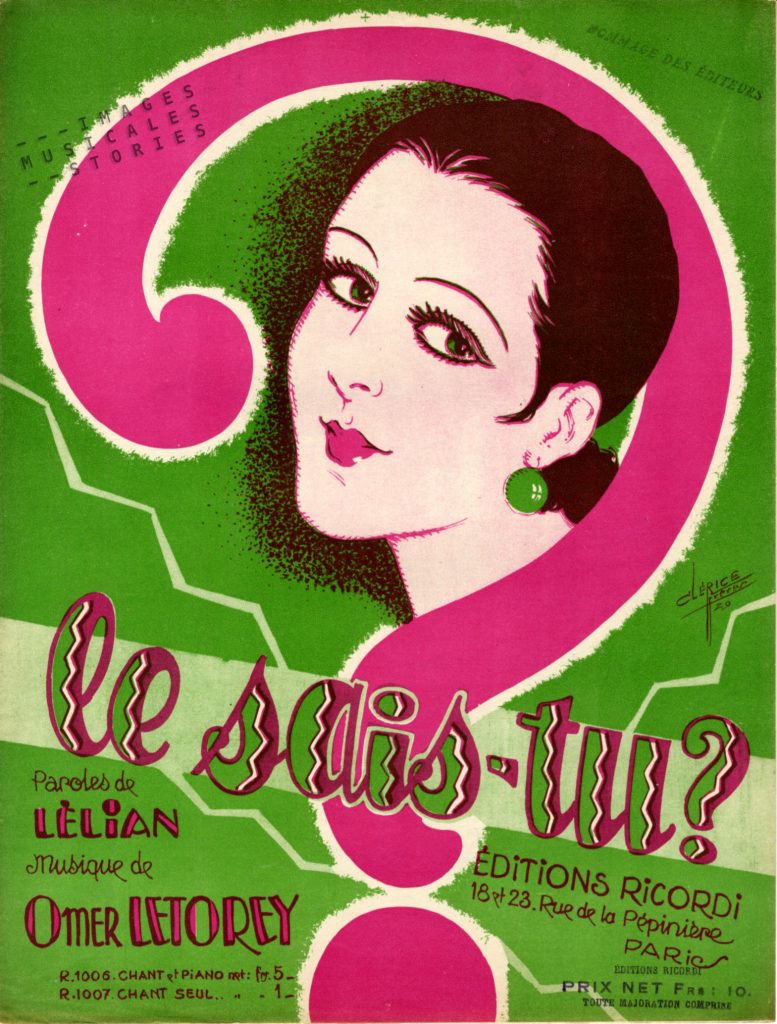

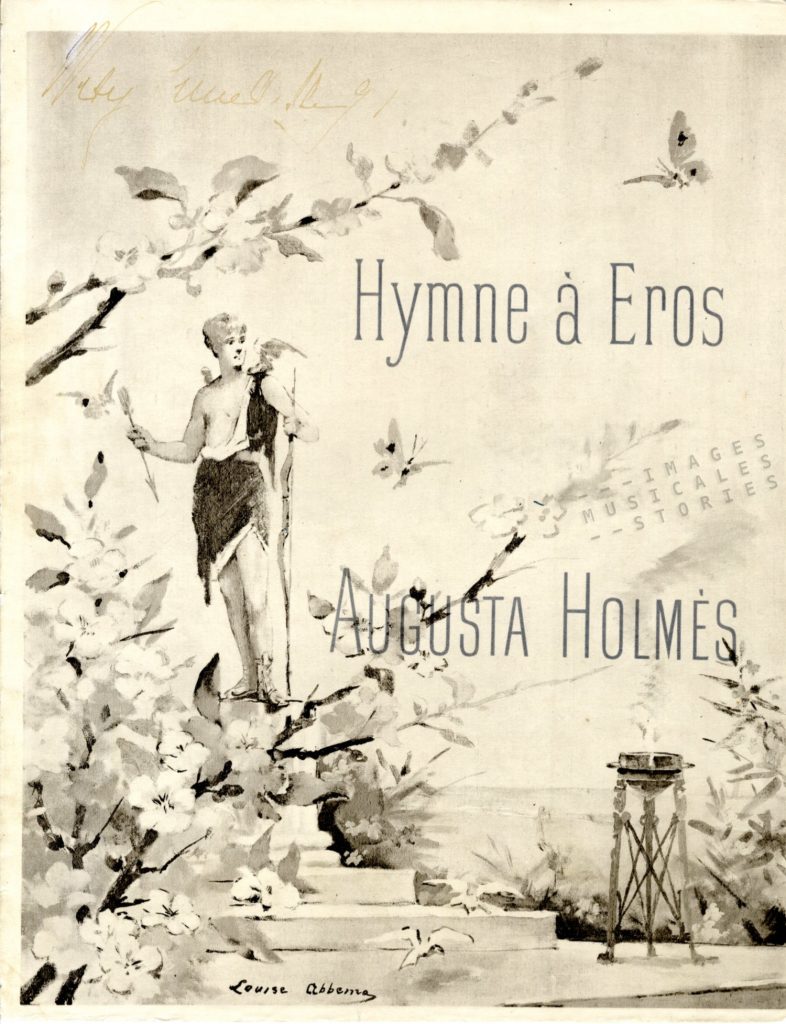

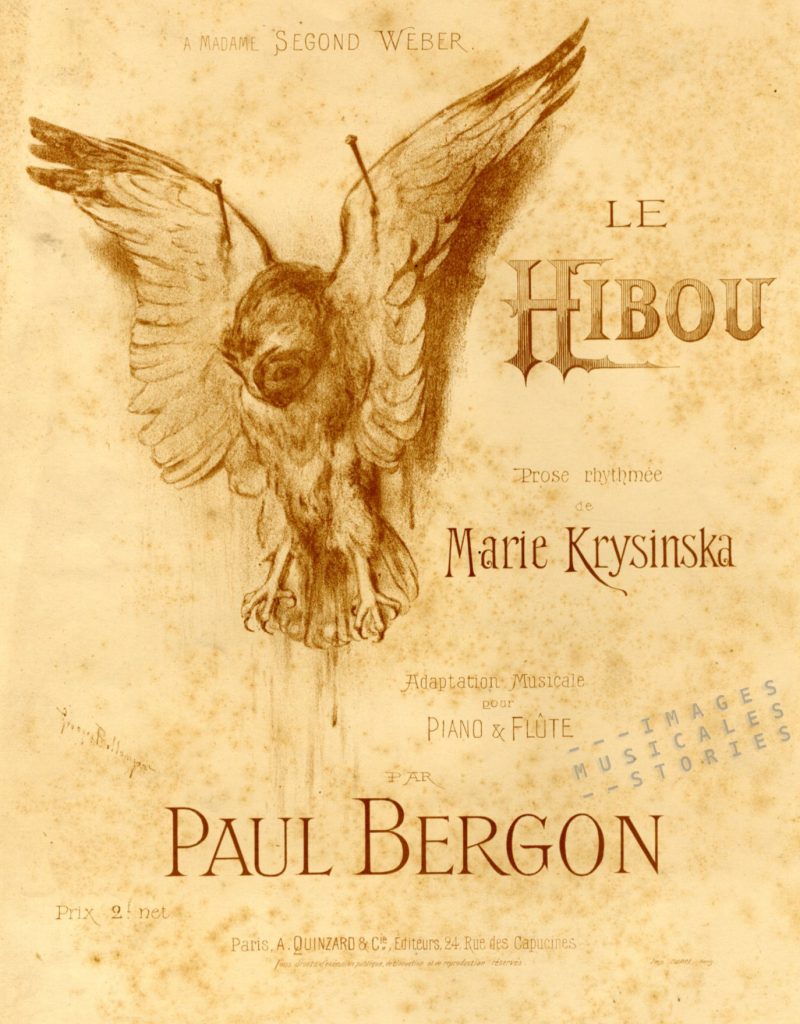

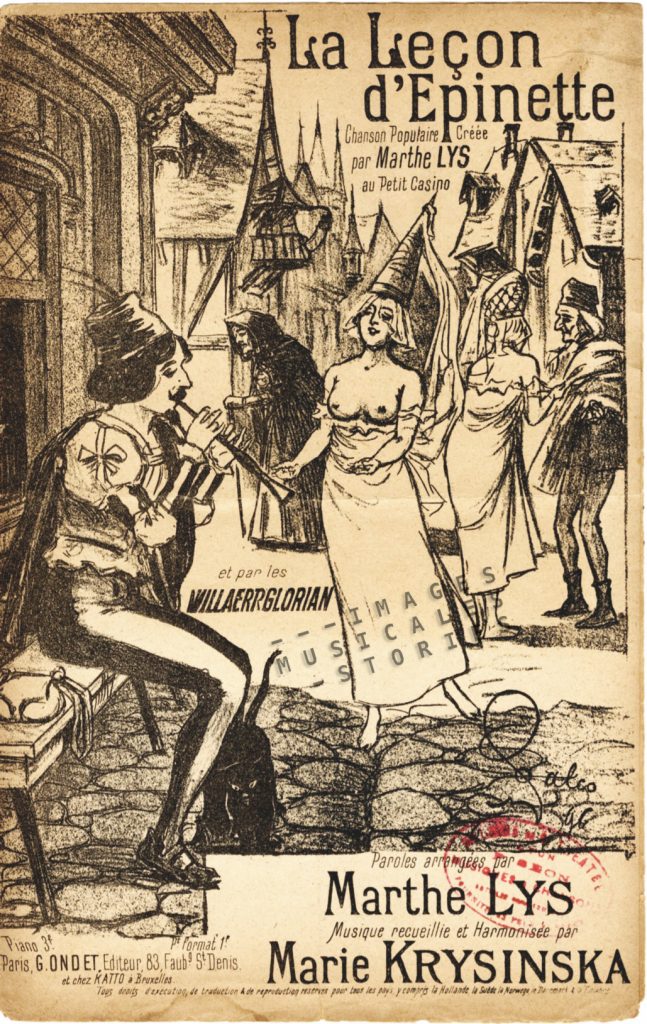

The cover is by lithographer Georges Bellenger, the husband of Marie Krysinska who wrote the poem Le Hibou. As a young woman of the Polish upper middle class Marie Krysinska (1857-1908) entered the Parisian conservatoire where she studied composition and harmony. Soon however she would abandon her classes to follow a more offbeat course of life. Krysinska discarded the conventional musical forms in favour of a freer form of expression. She started to experiment with a new artistic form in which she would mix music, theatre and poetry.

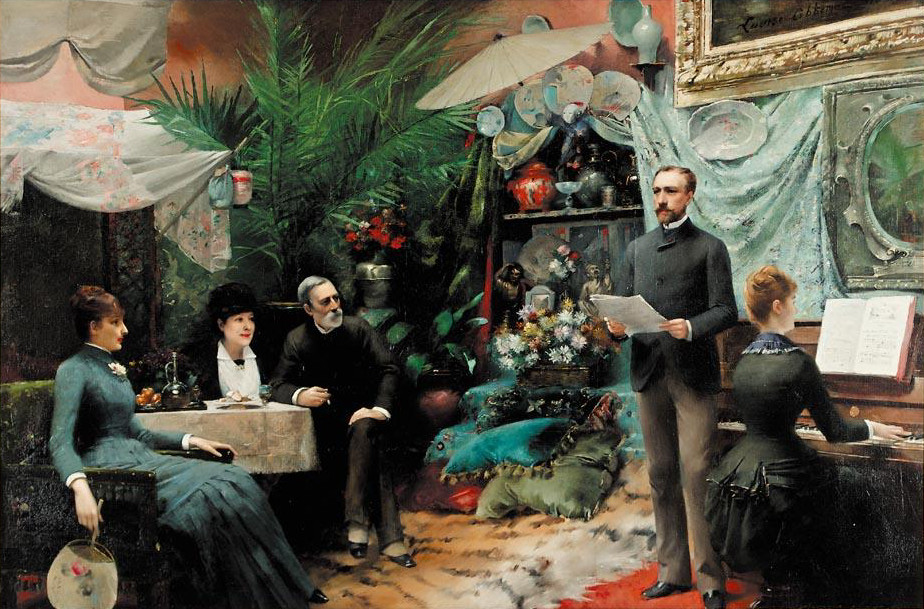

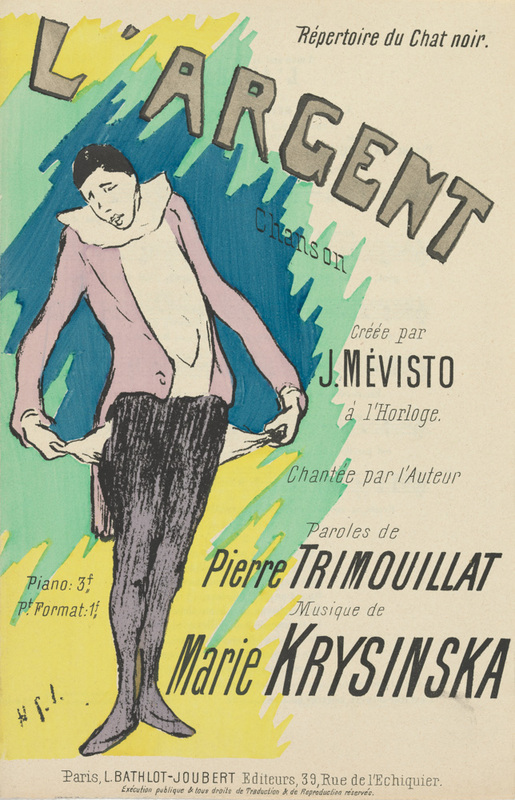

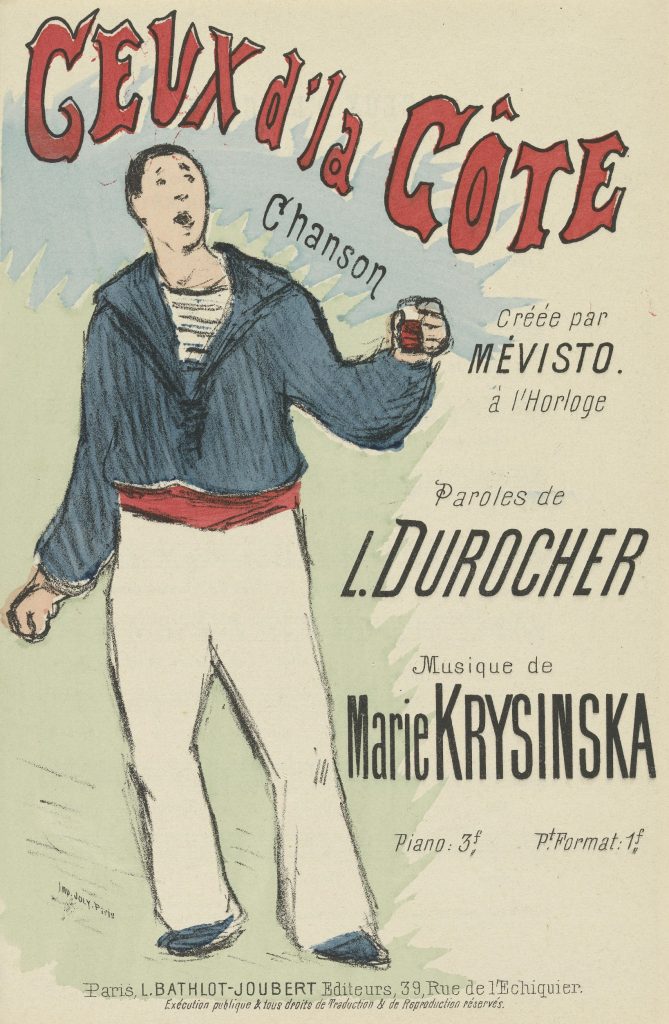

She mingled with other free spirits and was the only female founding member of the literary circle Les Hydropathes (meaning those who are afraid of water and prefer alcohol). She participated in similar nonconformist gatherings: the Zutistes, Jemenfoutistes and Hirsutes. They all came together at Le Chat Noir, the famous cabaret in bohemian Montmartre that embodied the spirit of the Belle Epoque.

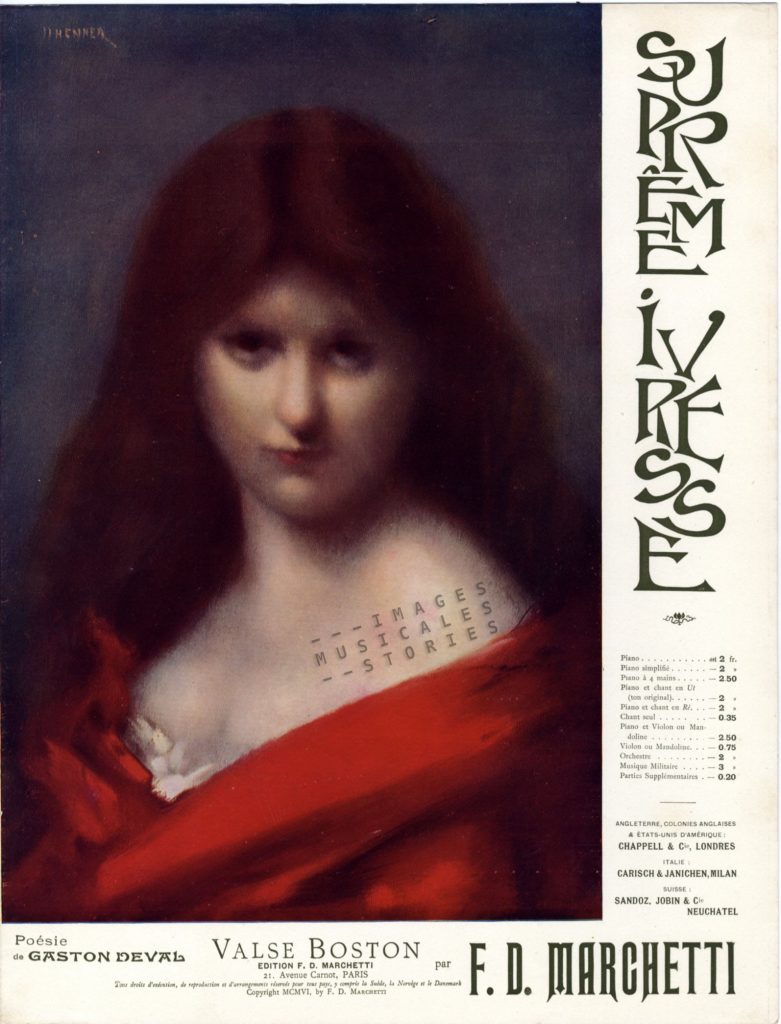

At Le Chat Noir Marie Krysinska became the house pianist for a while. It was an exciting place to be for a young artist. Moreover, as a woman her role was unique: she accompanied singers, composed songs, and also performed her own poetry on stage. At that time, interpreting romances by accompanying oneself was customary in intimate or mundane settings such as salons, but quite unusual in front of a large audience.

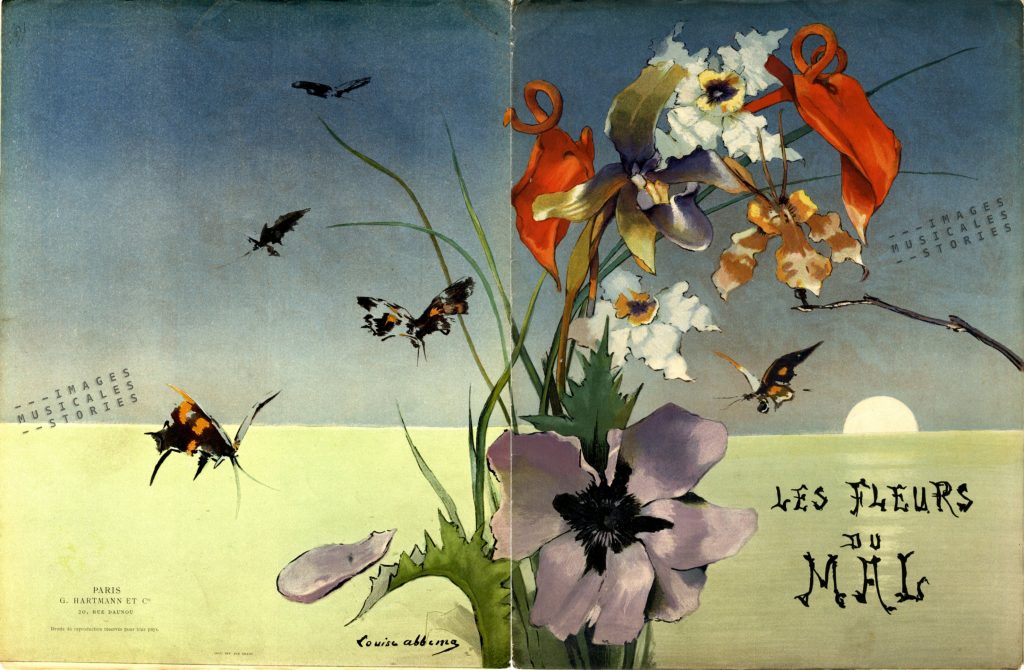

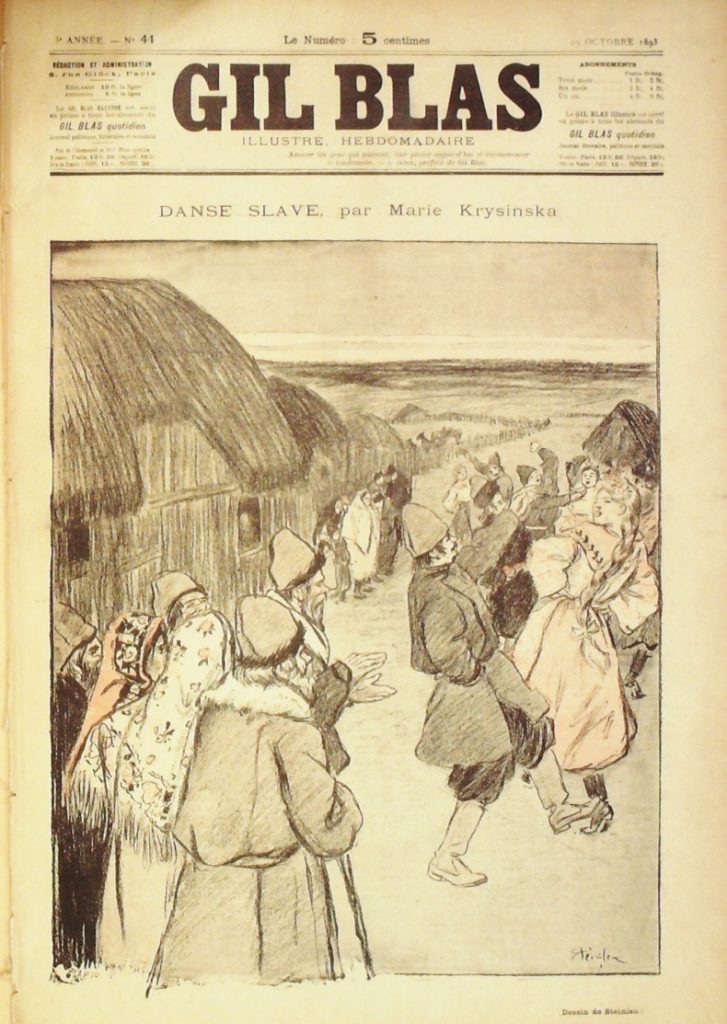

Le Chat Noir published a weekly magazine which would regularly print Marie Krysinska’s poems. Most of the poems of her poetry collections Les Rythmes Pittoresques were first published in Le Chat Noir. Many were dedicated to artists or personalities of the cabaret. Her verse would also appear in other literary magazines like Gil Blas, La Vie Moderne, and in the French feminist newspaper La Fronde.

Marie Krysinska was at the centre of the debate surrounding the birth of French vers libre or free-verse poetry in the 1880s. Free verse does not use the basic rhythmic structure, rhyme, nor any musical pattern but more or less follows the rhythm of natural speech. In the quarrels over the origin of free verse, Krysinska and Gustave Kahn, a male symbolist poet, vied for the title.

It was in fact Krysinska’s poem Le Hibou, published in La Vie Moderne in 1883, that triggered this debate. According to his own writings, Kahn came to see this poem, by accident, when he was serving his country in Tunisia. To his great surprise Le Hibou was written in free verse, looking precisely like his own try-outs. He claimed that it was signed by a person who knew him very well and who used his aesthetics during his forced absence. Thus Kahn christened himself father of the free verse while accusing Krysinska of plagiarism. Krysinska had to counter this if she wanted to stand up for her contribution to literature. She managed to prove that her free-verse poems had been published five years earlier than those of Kahn (*).

In the ensuing public debate it became bon ton to mock Krysinska. The French essayist Laurent Tailhade, attacked her and other female performers virulently:

“I never have encountered a more deplorable gathering of ugliness, or a more unpleasant version of feminine clothing. One or two pretty women, lost in the midst of these crooks, gave the eyes a needful rest. Meanwhile the other ones performed their show. Among these ladies was a poetess with some fame between Boulevard Saint-Michel and Montparnasse, the Polish Jew Marie Krysinska. She was seeking the attention of young men by childish airs and advances of an ape-like ingenuity. Big, fat and already far from morning glory, she undulated melodramas on a piano which had lost it sharps.”

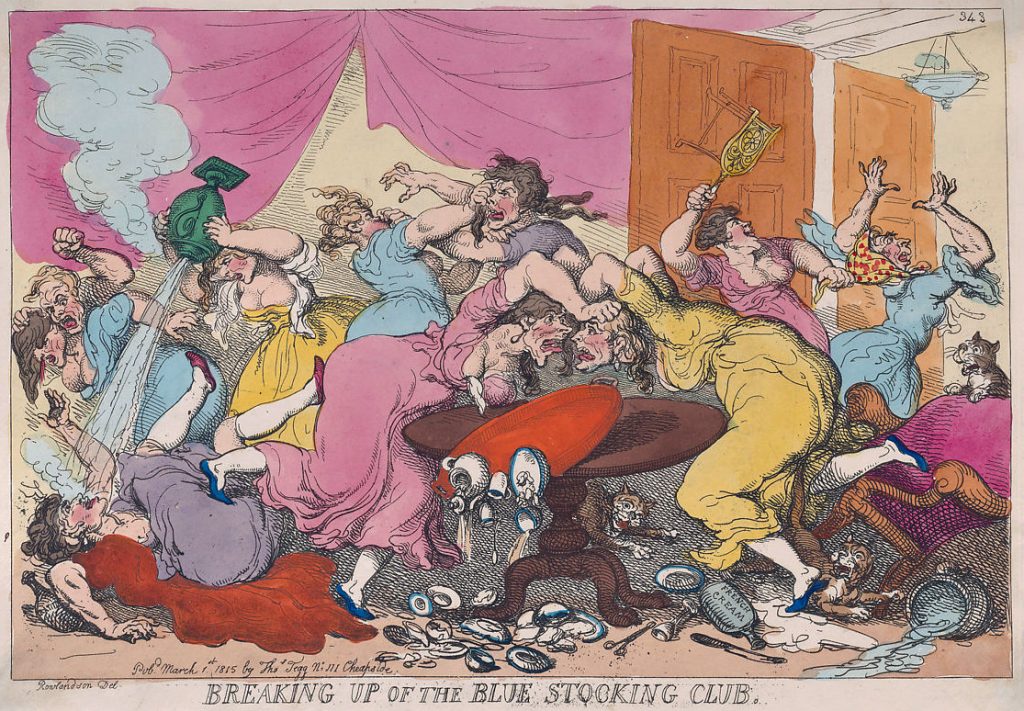

The same writer further ridiculed Krysinska in a poem in which he named her Marpha Bableuska, making allusions to the Blue Stockings that had already become a pejorative term by the late eighteenth century.

Apart from this female gender bashing, Marie Krysinska had to endure criticism and rejection by the symbolist movement. At the time of her dead, an obituary didn’t even acknowledge her poetry. Only her heydays at Le Chat Noir were remembered. Because of her beautiful and musical poetry Marie Krysinska though —in my humble opinion— deserves a better place in literary history.

Le hibou

Il agonise, l’oiseau crucifié, l’oiseau crucifié sur la porte.

Ses ailes ouvertes sont clouées, et de ses blessures, de grandes perles de sang tombent lentement comme des larmes.

Il agonise, l’oiseau crucifié!

Un paysan à l’oeil gai l’a pris ce matin, tout effaré de soleil cruel, et l’a cloué sur la porte.

Il agonise, l’oiseau crucifié.

Et maintenant, sur une flûte de bois, il joue, le paysan à l’oeil gai.

Il joue assis sous la porte, sous la grande porte, où, les ailes ouvertes, agonise l’oiseau crucifié.

Le soleil se couche, majestueux et mélancolique, – comme un martyr dans sa pourpre funèbre;

Et la flûte chante le soleil qui se couche, majestueux et mélancolique.

Les grands arbres balancent leurs têtes chevelues, chuchotant d’obscures paroles;

Et la flûte chante les grands arbres qui balancent leurs têtes chevelues.

La terre semble conter ses douleurs au ciel, qui la console avec une bleue et douce lumière, la douce lumière du crépuscule;

Il lui porte d’un pays meilleur, sans ténèbres mortelles et sans soleils cruels, d’un pays bleu et doux comme la bleue et douce lumière du crépuscule;

Et la flûte sanglote d’angoisse vers le ciel, – qui lui parle d’un pays meilleur.

Et l’oiseau crucifié entend ce chant,

Et oubliant sa torture et son agonie,

Agrandissant ses blessures, –ses saignantes blessures,–

Il se penche pour mieux entendre.

Ainsi es-tu crucifié, ô mon cœur!

Et malgré les clous féroces qui te déchirent,

Agrandissant tes blessures, tes saignantes blessures,

Tu t’élances vers l’Idéal,

A la fois ton bourreau et ton consolateur.

Le soleil se couche majestueux et mélancolique.

Sur la grande porte, les ailes ouvertes, agonise l’oiseau crucifié.

(*) The debate on the vers libre authenticity is still going on. While some scholars attribute its original creation to Marie Krysinska, according to other researchers the ‘real’ first free verse was not written by Krysinska nor by Kahn, but by Arthur Rimbaud.