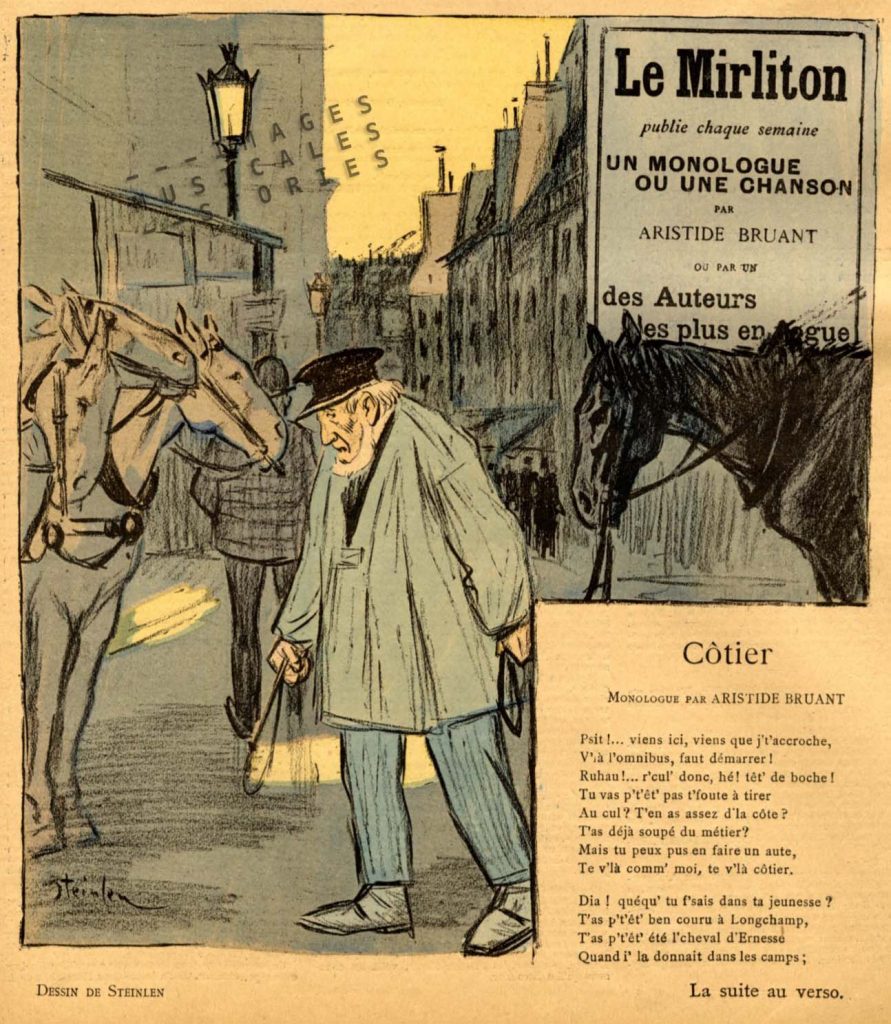

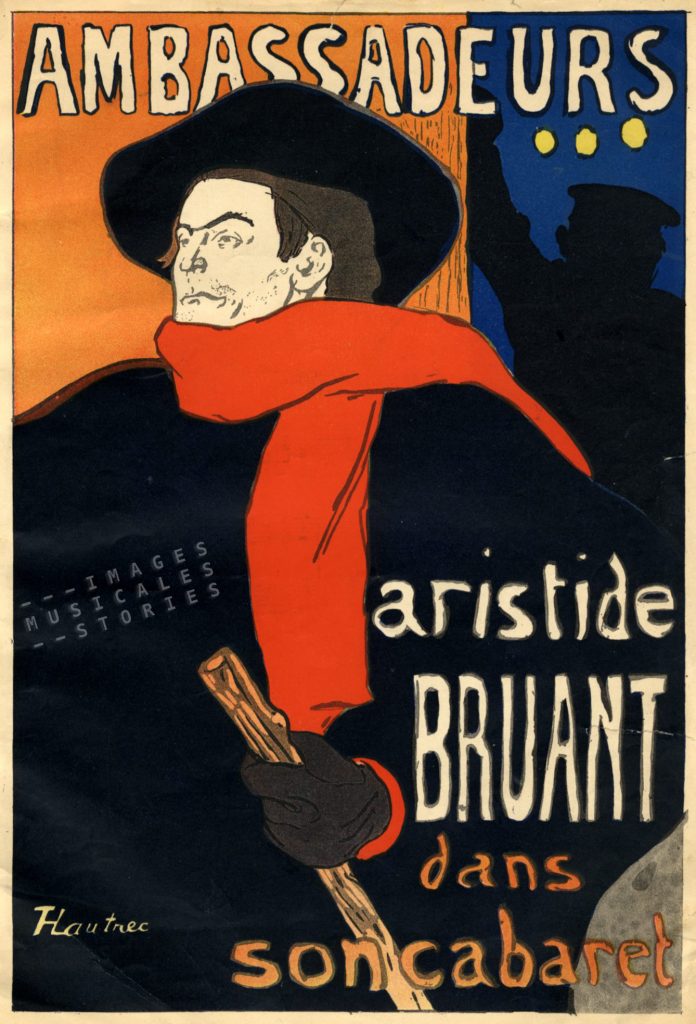

In 1885 Aristide Bruant (1851-1925) opened his Parisian cabaret, Le Mirliton. At the same time he started to publish a journal, with an identical name. Bruant filled his four-page periodical with the lyrics of his songs, poetry, news about spectacles and of course about Bruant himself. He commissioned Theophile Steinlen to create the covers for his Mirliton journal. It is told that Bruant was friends with Toulouse-Lautrec, who immortalised in 1892 the disdainful singer on a poster for the Ambassadeurs cafés-concert.

Bruant’s songs were chansons réalistes about working-class Parisian people written in street slang, the proletarian argot that borrowed its vocabulary from thieves and artisans. He even published the Dictionnaire de l’argot au XXe siècle for those who needed help in understanding the difficult Parisian jargon.

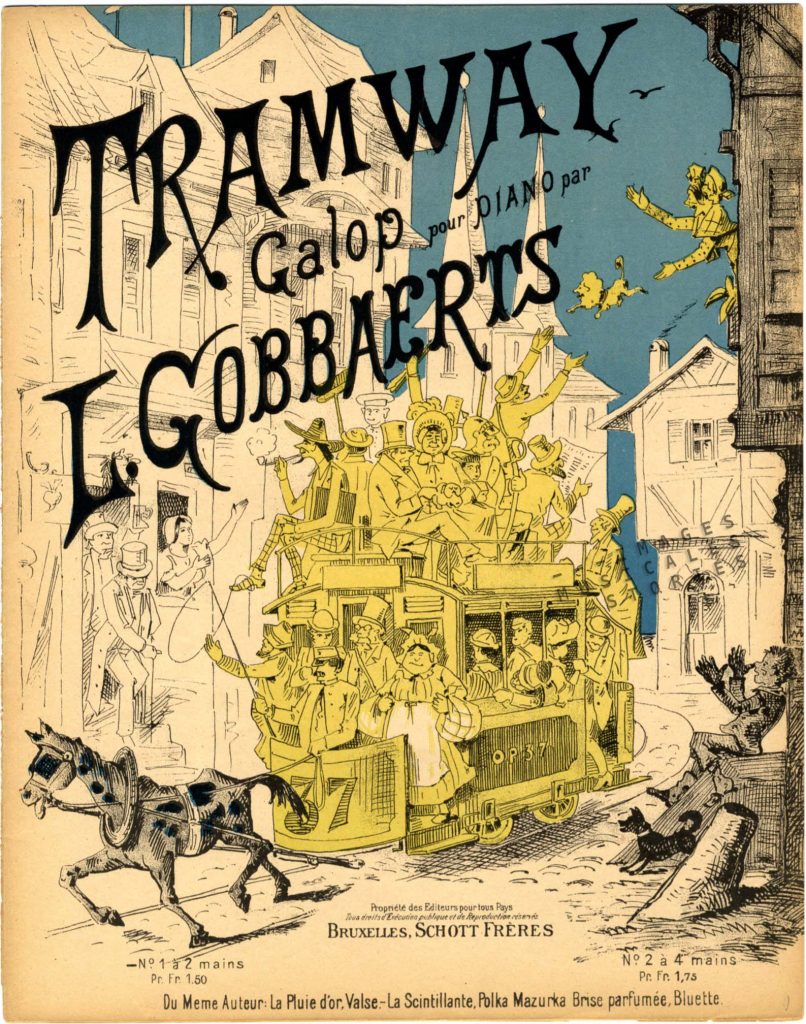

The song above is about an elderly côtier who talks to his worn-out horse. In the 19th century and in the beginning of the 20th, men with extra horses (chevaux de renfort) stood at the bottom of steep slopes to help horse-drawn carriages and carts to climb up the hill. These côtiers frequently offered their services to the coachmen of omnibus lines.

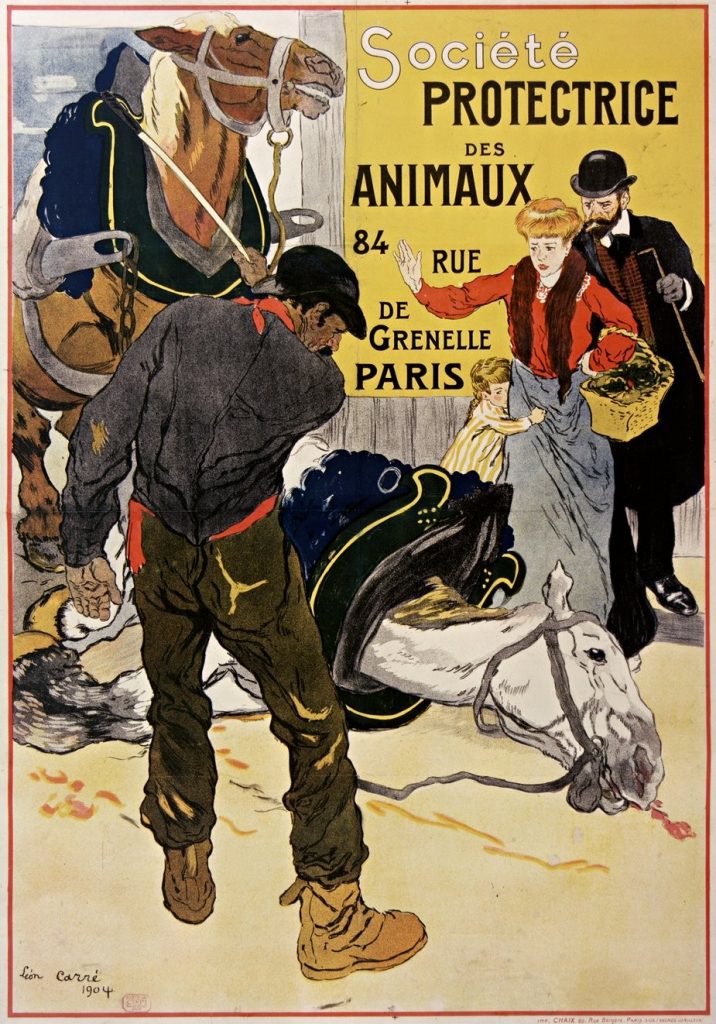

Many of the drivers didn’t care for animal welfare. They were brutal to their horses who were thus being reduced to live machines. It is but in 1843 that a Paris police prefect signed the first decree to prohibit drivers from hitting their horses with the handle of their whips. And 1850 saw the first law for the protection of domestic animals.

It was also the start for the Society for the Protection of Animals (SPA). In Le Cheval à Paris de 1850 à 1914 we read the following chilling account:

“More importantly, the SPA obtained authorization for veterinarians to immediately treat horses suffering from sunstroke on the public road, without having to wait for the owner’s agreement. At least one would no longer see these animals dying on the road for hours on end, in excruciating conditions, because no one had been able to get hold of its owner. When the owner remained untraceable, one had to call the commissaire de police who then entrusted the animal to the renderer. The Macquart and Tétard knackers then arrived with their car, (…) they hauled up the horse with a hoist and led it either to the animal pound or to the veterinarian (…) or if the horse meanwhile had died, to their own establishments.”

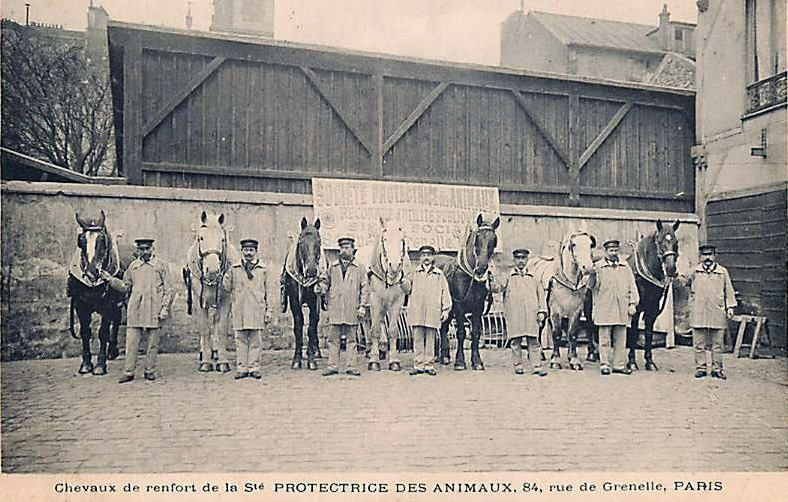

From 1890 on the SPA had their own chevaux de renfort in Paris, stationed beneath recognisable cast-iron poles. They also employed their own côtiers.

Bruant’s song ends with the following morbid words spoken by the côtier to his horse:

Et pis après c’est la grande sorgue,

Toi, tu t’en iras chez Maquart

Moi, j’irai p’têt ben à la morgue..

And then arrives the big night,

You will go to Maquart

I’ll go to the morgue.

So the poor horse was destined for Maquart, the horse knacker established in Aubervilliers since 1841. In 1886 Maquart processed 300 to 350 horse carcasses per month, using 5 industrial boilers. At the beginning of the 20th century Léon Bonneff describes Aubervilliers, a commune in the north-eastern suburbs of Paris, as follows “…there exists a terrible and charming village. In it merge the waste, the residue and the nameless filth of a capital city. Will go there: dead horses, horses to be slaughtered, horses that veterinarians reject for consumption*, horses that almost die on the street; there passes the blood of slaughterhouses in hot and steaming barrels.”

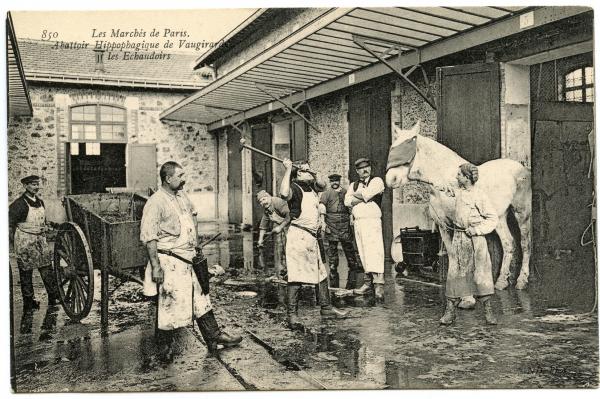

* Yes, the French eat horses. This postcard gives a macabre view of a slaughterhouse at a market for the consumption of horse meat.

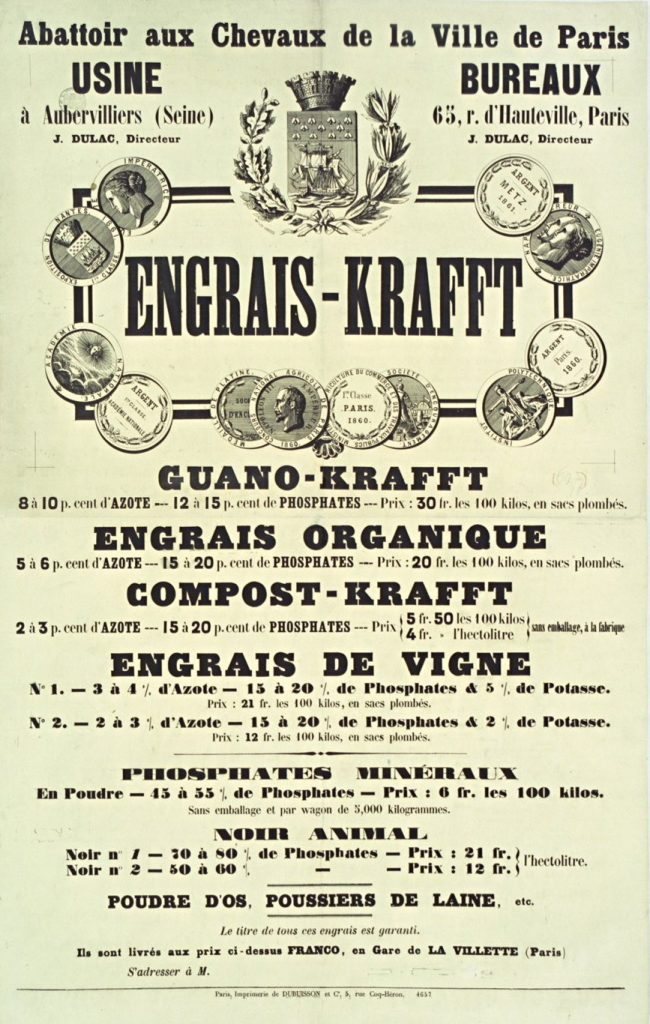

All that organic waste of the horses created foul smelling tanneries and fertiliser factories in the neighbourhood of slaughterhouses and knackeries. The côtier’s poor horse probably would end up as glue or fertiliser. Or as something that took my attention in the publicity for the slaughterhouse: noir animal. I had never heard of this but I learned that it is bone char.

All that organic waste of the horses created foul smelling tanneries and fertiliser factories in the neighbourhood of slaughterhouses and knackeries. The côtier’s poor horse probably would end up as glue or fertiliser. Or as something that took my attention in the publicity for the slaughterhouse: noir animal. I had never heard of this but I learned that it is bone char.

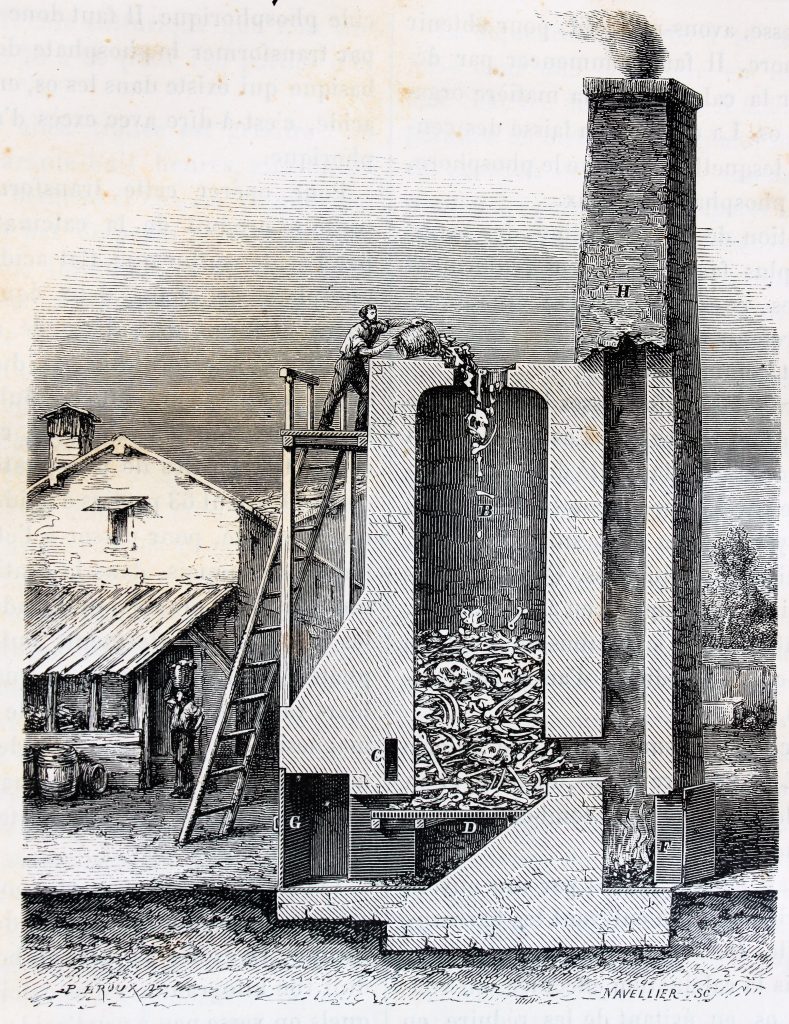

To make bone char the animal bones are heated at incredibly high temperatures with low oxygen concentration, and are thus reduced to carbon. Historically, bone char was (and still is) used in sugar refining as a discolouring and de-ashing filter agent, particularly for cane sugar. Be careful vegans. Bone char filters are not used to process beet sugar.

Bone char is also used as a black pigment for artist’s paint and drawing ink because of its deepness of colour. Bone black and ivory black are artists’ pigments which have been long in use. I will never look in the same way at Manet’s beautiful intense ivory black.

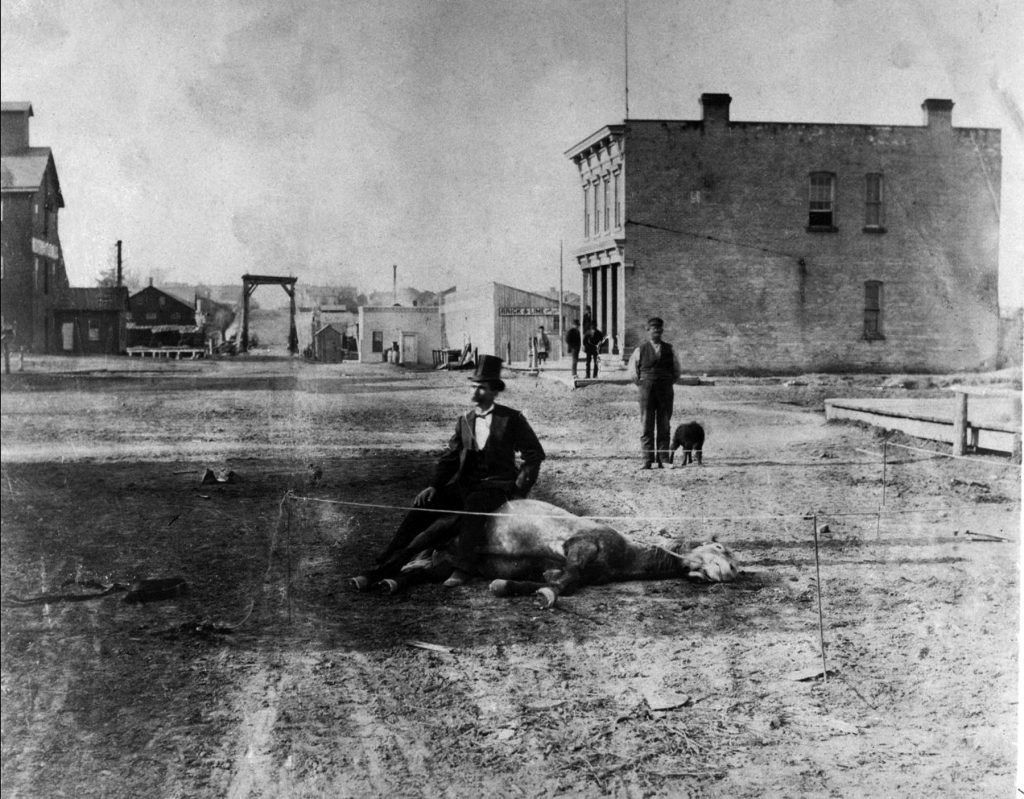

During our research we came across this puzzling photograph of the strange relation between man and dead horse — no comment.

Time now for a light-hearted and very danceable song to promote an animal-friendly lifestyle. Get those vegan vibes, here is Macka B!

Reference: ‘Le Cheval à Paris de 1850 à 1914’ by Ghislaine Bouchet (Mémoires et Documents de l’Ecole de Charte n° 37, Librairie Droz, Genève, 1993)