By showing this young lady with two enormous hatboxes swinging on her arms, de Valerio marks her as a milliner or une modiste (a hat maker or seller). She seems in a festive mood and is singing the careless refrain of the Chanson des Catherinettes.

I had never heard of Catherinettes before, prompting me to dig into its meaning and history.

According to legend Catherine of Alexandria was imprisoned by the Roman emperor Maxentius because she was a Catholic. We are in the early 4th century. After having unsuccessfully tried to break her faith, he strangely proposed her to marry. But Catherine had consecrated her virginity to Jesus Christ and rejected his offer. Maxentius, smitten by the beautiful but devout young lady, did not take no for an answer: he tortured Catherine on a spiked breaking wheel. She was miraculously saved from that ordeal: instead of her bones, the wheel itself broke. Sadly, her besotted persecutor showed grace nor mercy, and gave the order to behead her. That is how Catherine became venerated as a virgin martyr and was nominated patron saint for maidens and spinsters.

From the 12th century on the French started to honour Saint Catherine on each 25th of November. That day, Sainte-Catherine, was seen as a coming of age feast for unmarried women who had reached the age of 25. With flowers and ribbons unmarried girls used to create a beautiful headdress to coiffe (or cap) Saint Catherine’s statue in the church. When the maidens were 25 years old they stuck one needle in the headdress. This was meant as a warning: don’t wait any longer to find a husband. A second needle was pinned when they were 30 (time is running out!), and a third one at 35. Then one had definitely become a spinster with all hope lost…

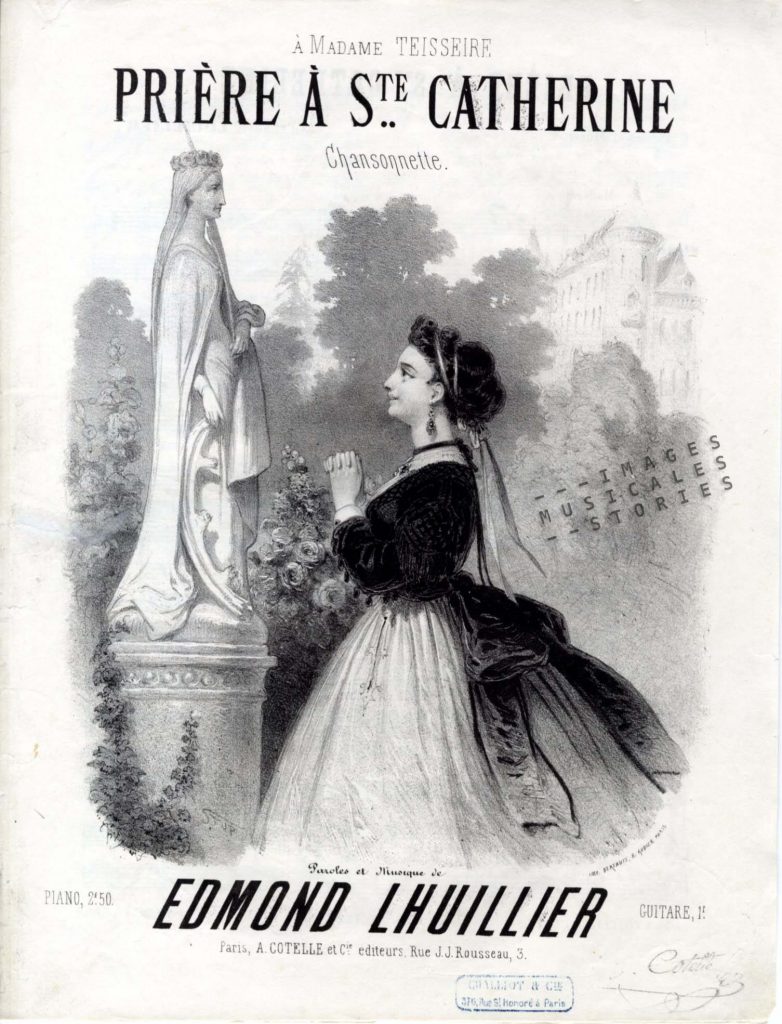

The expression ‘coiffer Sainte Catherine‘ became synonymous with still being a single woman at (or after) 25. On the day of Sainte-Catherine these single women prayed for a future husband to their patron saint. But to assist the saint in helping these young women to find a suitor, a ball was arranged on Saint Catherine’s day all over France.

At the beginning of the twentieth century the tradition of la Sainte-Catherine was practically lost. But then, rather suddenly, it shifted from a catholic peasant celebration to an exuberant Parisian festivity. There and then it became very popular. In the modern age women had entered the workforce on a large scale. In Paris that was particularly so in the fashion trade. So Saint Catherine’s day became a celebration for working girls, which was at that time more or less synonym with unmarried girls, because once a girl married she was also supposed to stop working. Sainte-Catherine thus became especially popular in fashion houses and among milliners, although also shop-girls and typists participated. It is those unmarried girls, at the age of 25, that were called Catherinettes.

A typical Saint Catherine’s day would follow the next scenario. At breakfast the Catherinette admired her greeting cards, received from friends and colleagues, wishing an abundance of potential suitors and reminding her that the time had come to find that much sought after husband. Celibacy for ‘elderly’ women was still stigmatised, as witnessed by the postcard below.

A typical Saint Catherine’s day would follow the next scenario. At breakfast the Catherinette admired her greeting cards, received from friends and colleagues, wishing an abundance of potential suitors and reminding her that the time had come to find that much sought after husband. Celibacy for ‘elderly’ women was still stigmatised, as witnessed by the postcard below.

In the morning at work, her colleagues had made her a special hat. At first these hats were quite simple, resembling a traditional coiffe. The predominant hues of the hats were yellow and green, the customary colours of Saint Catherine. Usually attached to it was a small sprig of orange blossom, the traditional flower of the bridal bouquet.

But year after year these hats were more elaborated upon, and became more intricate especially those from the hat-making and dressmaking trades.

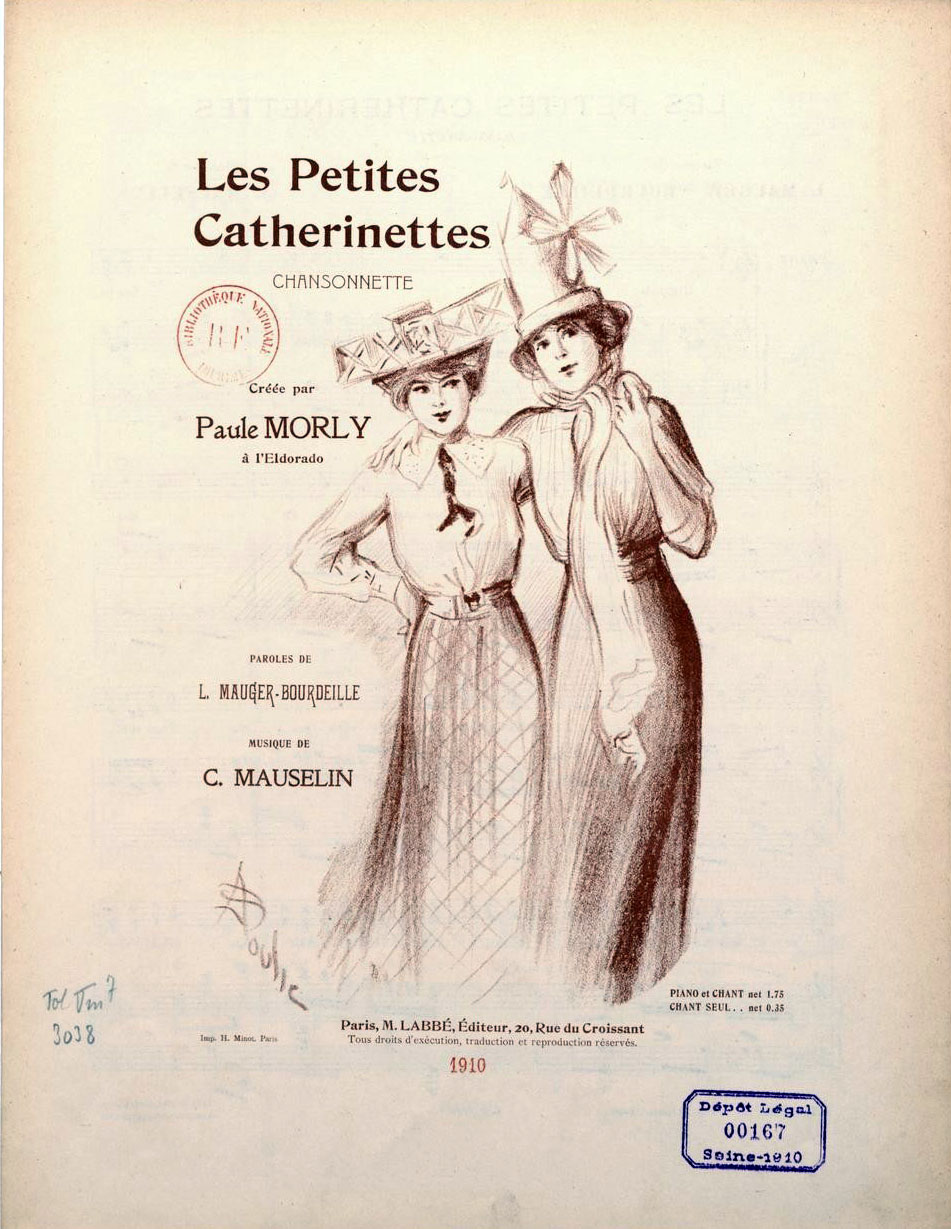

The themes of the hats sometimes followed contemporary events (1), as one sees on the sheet music cover for ‘Les Petites Catherinettes’. The illustrator got his inspiration from a press photo dated November 25, 1909.

The Catherinettes would wear their hats like a trophy throughout their festive day. At work the Catherinettes and their colleagues were offered refreshments and food.

Then they would take to the street, dancing and singing.

Later in the day the Catherinettes could attend a hat contest, or try to become elected queen for the day. The jury for these competitions was composed of renowned artists and sports personalities.

In the evening, dressed in their best attire, the Catherinettes accompanied by their friends and colleagues, went to the ball of Sainte-Catherine where they could perhaps meet their future husband…

Saint Catherine’s male counterpart is Saint Nicolas, protector of children and unmarried men by age thirty. So men were given a respite of 5 years over the women. But the hat for their Saint Nicolas day was definitely less exciting, looking more like a dull nightcap. The Saint Nicolas day for bachelors never became a great success. If we may rely on the postcards, it was not intended for the alpha males…

Fashion houses, especially in the haute couture, became particularly attached to Saint Catherine’s tradition. In the ateliers the festival was a big deal and sets and costumes were created on various themes. They held large parades to show off their wares

Fashion houses, especially in the haute couture, became particularly attached to Saint Catherine’s tradition. In the ateliers the festival was a big deal and sets and costumes were created on various themes. They held large parades to show off their wares. To this day, the renown houses like Chanel still hold on to the yearly tradition. Though I am happy to see that the festival is no longer ‘Ladies only!‘.

If you have time for a (virtual) stroll in Paris, take a walk to the square Montholon in the rue Lafayette. In the shade of its tall oriental plane trees, you can admire the statue of five exhilarated Catherinettes ready for the ball.

(1) The baffling hat with the biplane was probably a tribute to Louis Blériot who became world-famous for making the first aeroplane flight across the English Channel in July of the year the photo was taken (1907). The hat with the Spanish-looking windmill likely illustrates the expression ‘jeter son bonnet par-dessus les moulins’ or ‘to throw one’s bonnet over the windmill’. It refers to Don Quixote who, while tossing his hat over a windmill, imagines that he is challenging a giant.