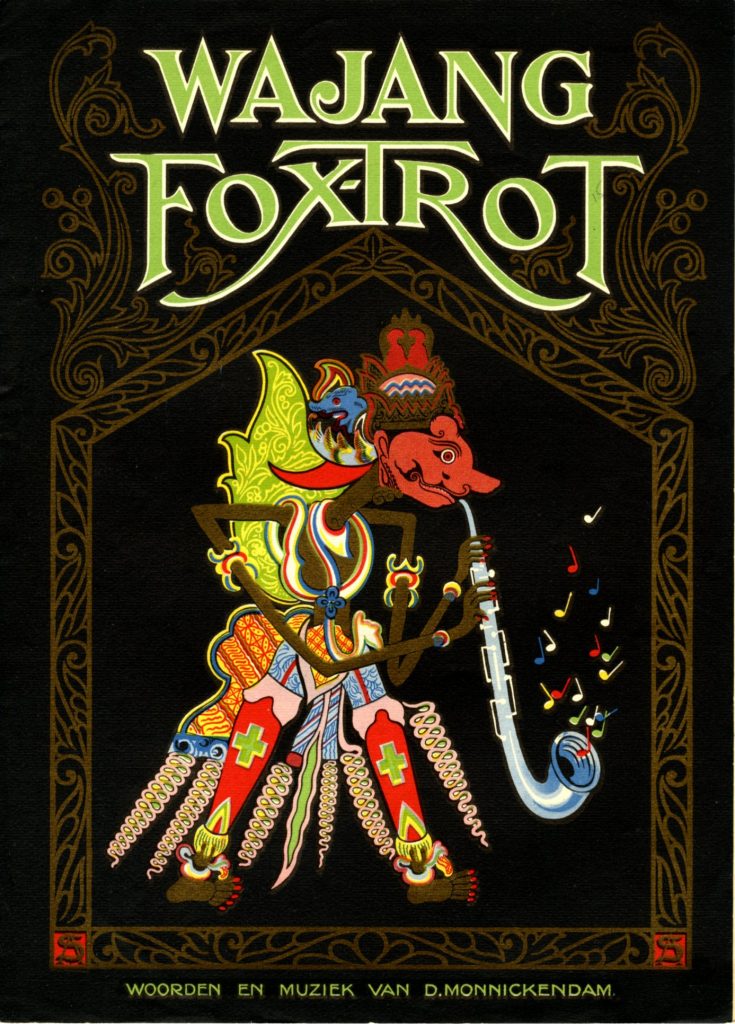

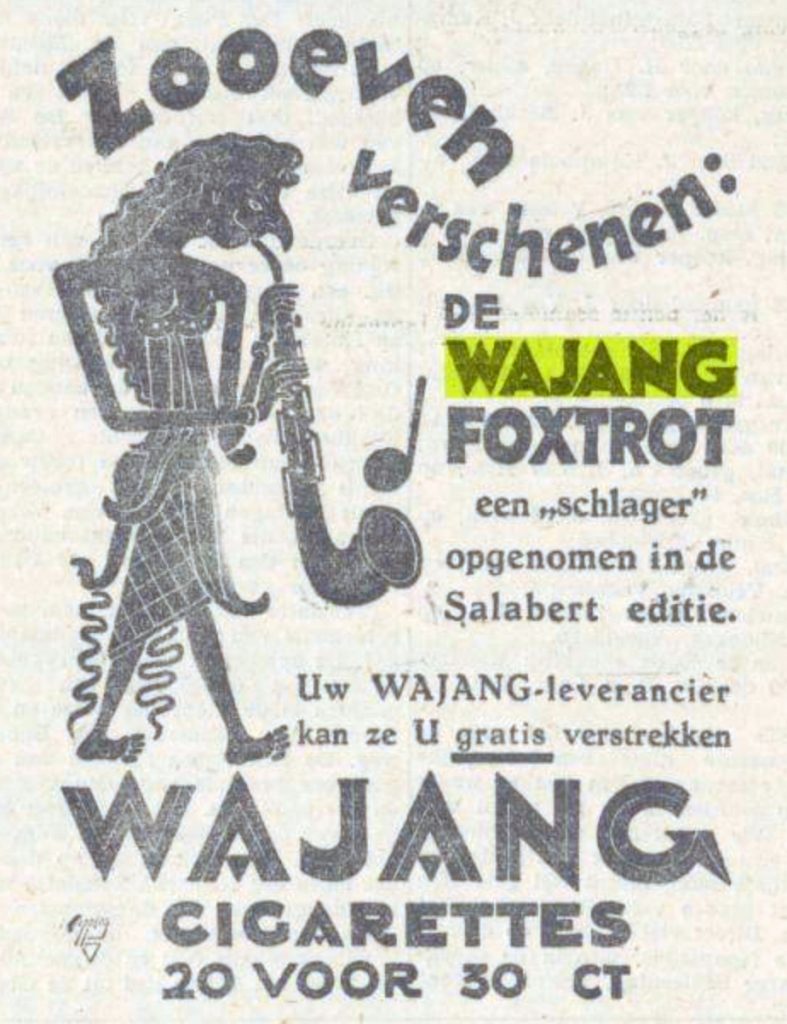

In our sheet music collection we found a second Dutch song promoting cigarettes. Its colourful cover shows an Indonesian wayang puppet playing the saxophone, mixing East and West. Wayang kulit is the traditional puppet-shadow theatre in Indonesia. The Wajang cigarette brand was launched in 1930. From a Dutch newspaper announcement we learn that the Wajang Fox-Trot song was published in the same year.

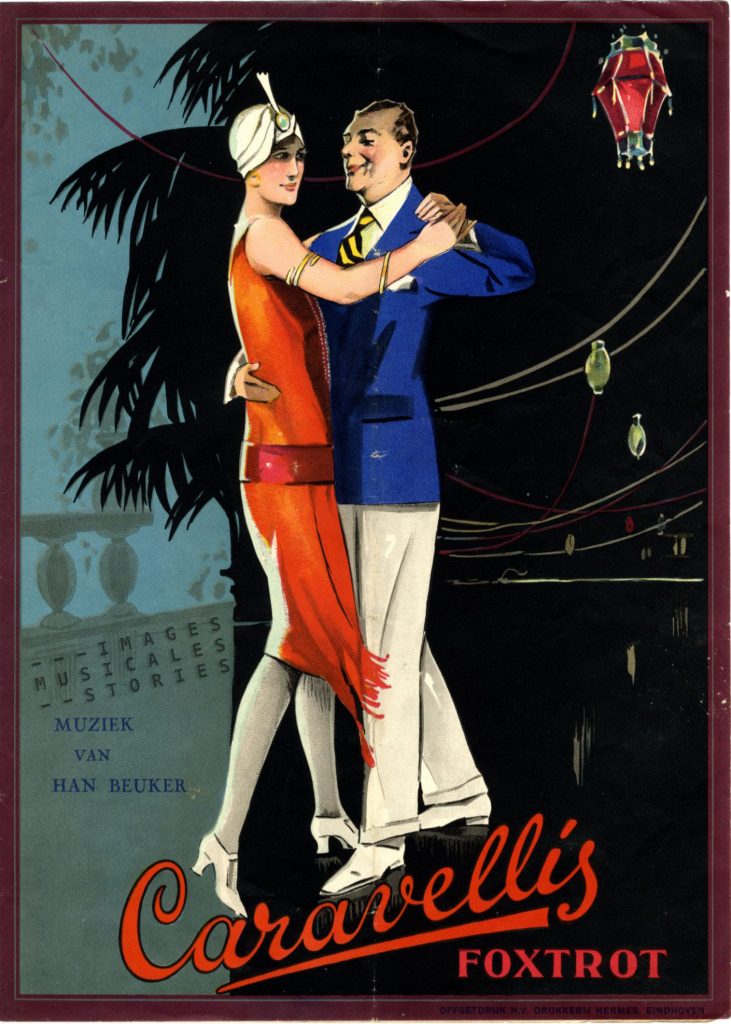

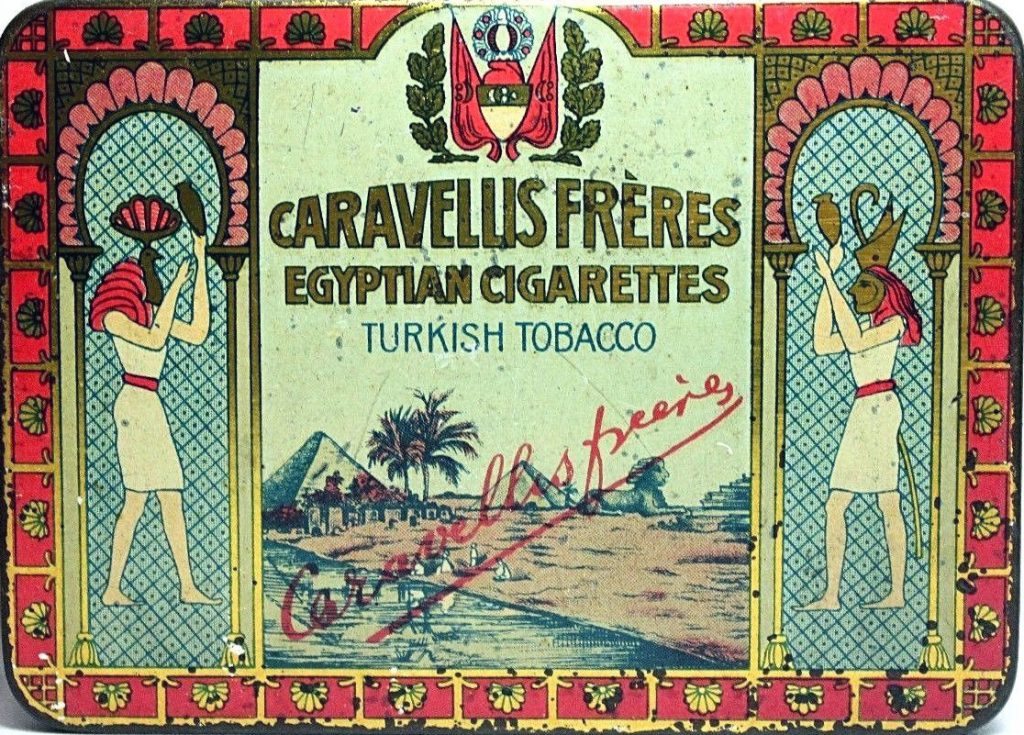

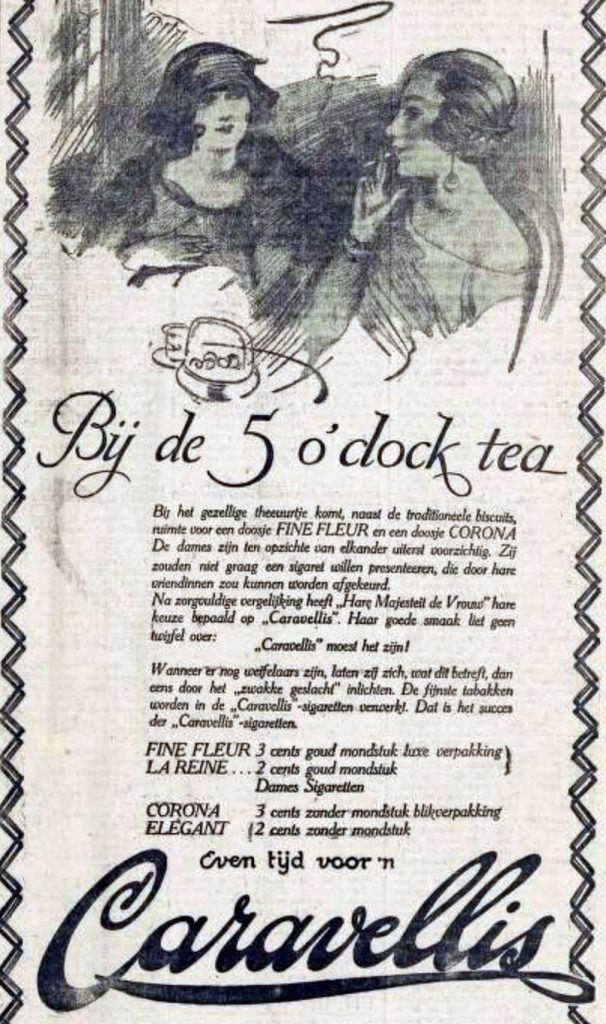

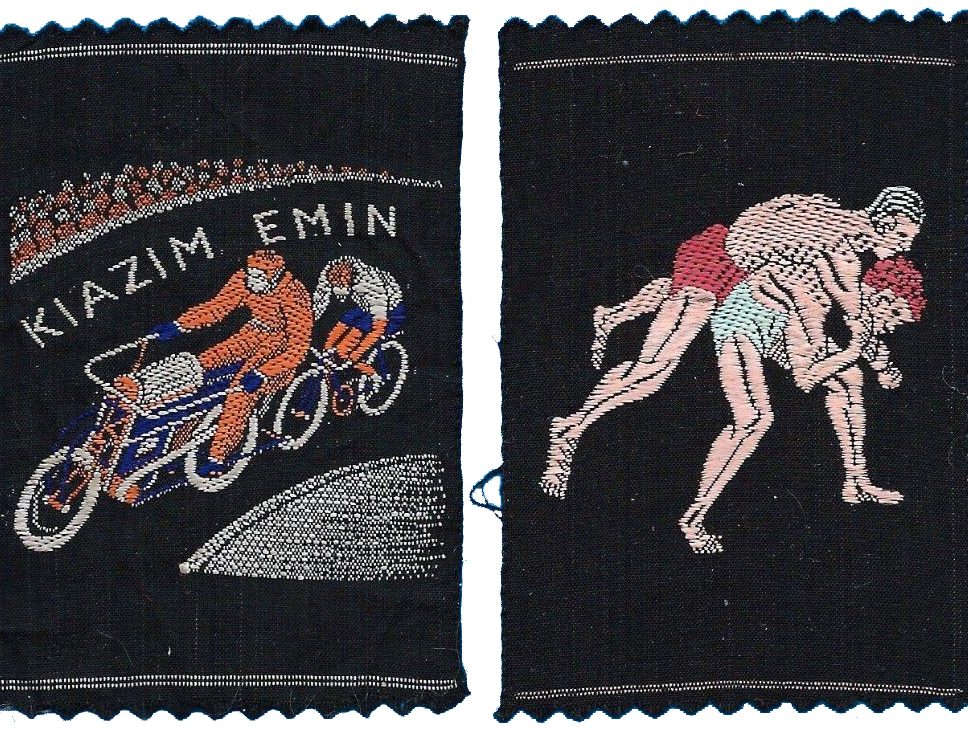

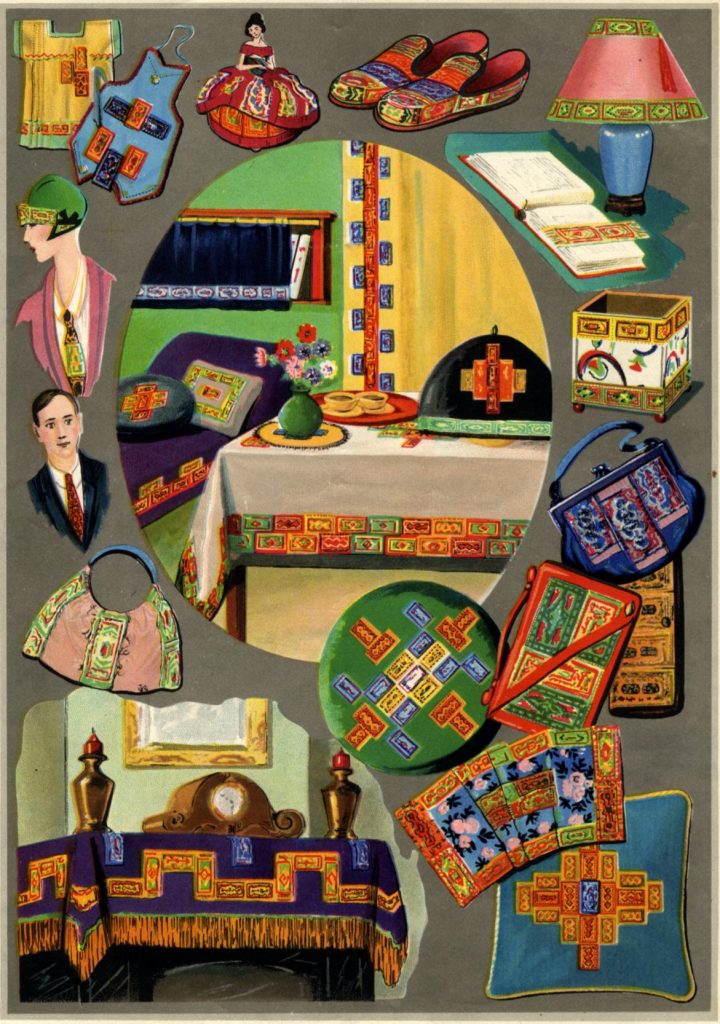

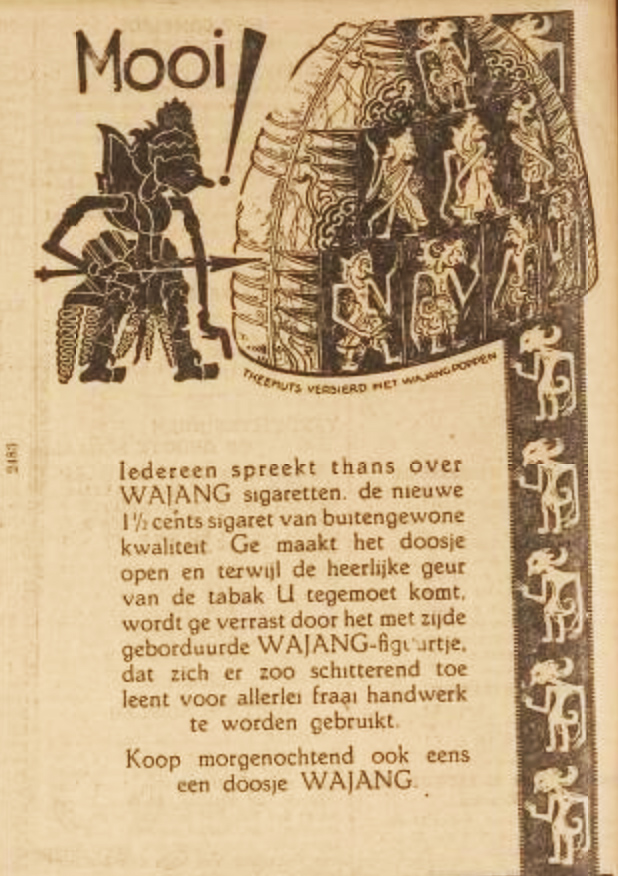

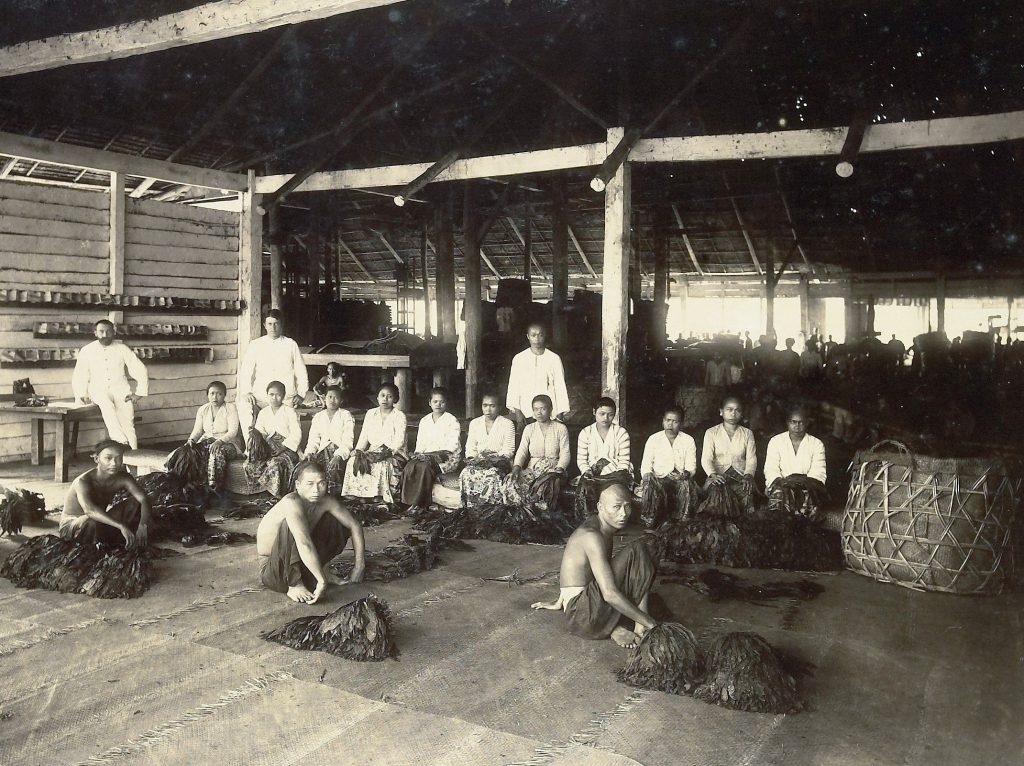

For centuries the Dutch had auctioned tobacco originating from the Spanish and Portuguese colonies. Then, in the 19th century the tobacco trade and industry grew more important as the tobacco plants were cultivated in the Dutch colonies in Borneo, Sumatra and Java. It is during the Dutch East Indies colonial period that Effendi Frères (again this French chic!) produced the Wajang cigarettes. Just like Caravellis cigarettes, Wajang offered to their customers a collection of tobacco silks: black patches embroidered with a variety of wayang figures. There were different series of these Wajang silks included in the cigarette packs. A newspaper advert suggested to use them for decorating a tea cosy: “You open the box and while the delicious scent of tobacco reaches you, you are greeted by the silk embroidered Wajang figurine, which lends itself beautifully to be used for all kinds of handicrafts.“

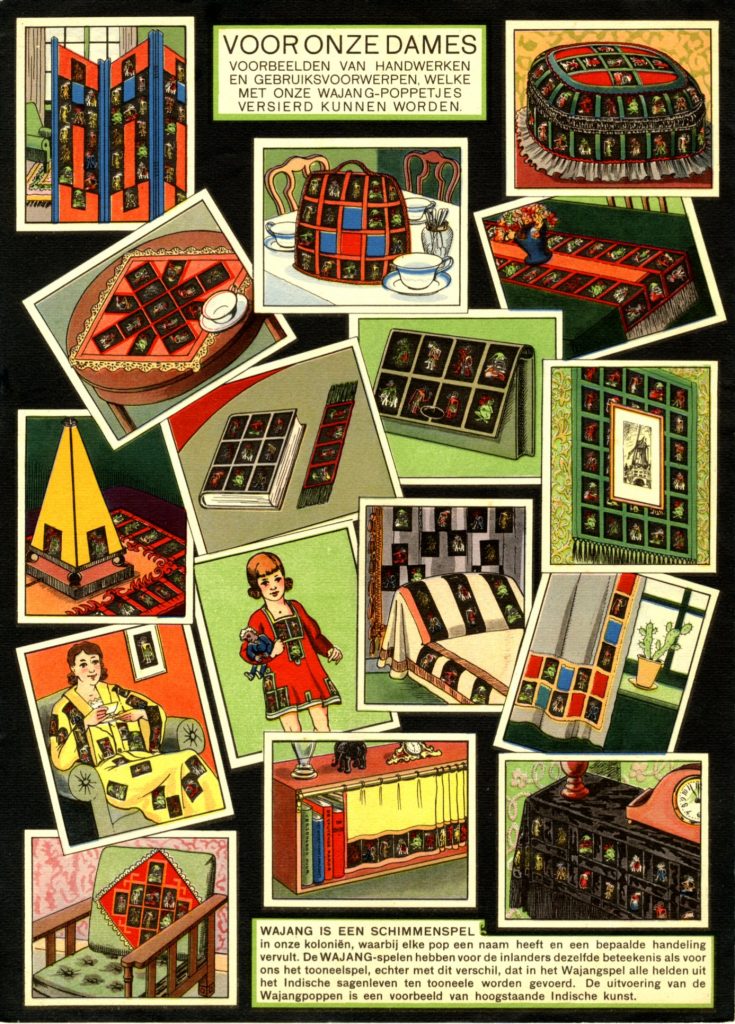

Just as for the previous Caravellis post, the Wajang back cover shows different ways to use the silks. My personal preference is the picture of the symbolic Dutch windmill hung before a tapestry of colonial Wajang silks.

Some ladies were extremely handy with the tobacco silks: this elaborate sleeveless evening gown was made from 1.280 Wajang tobacco silks!

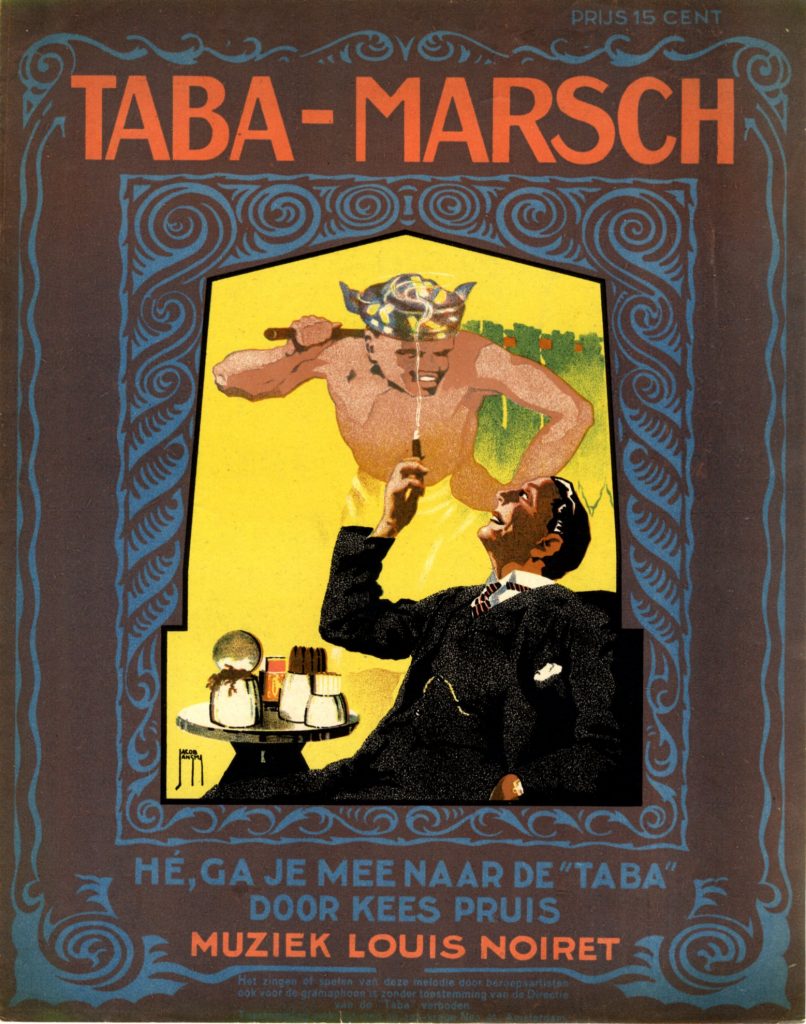

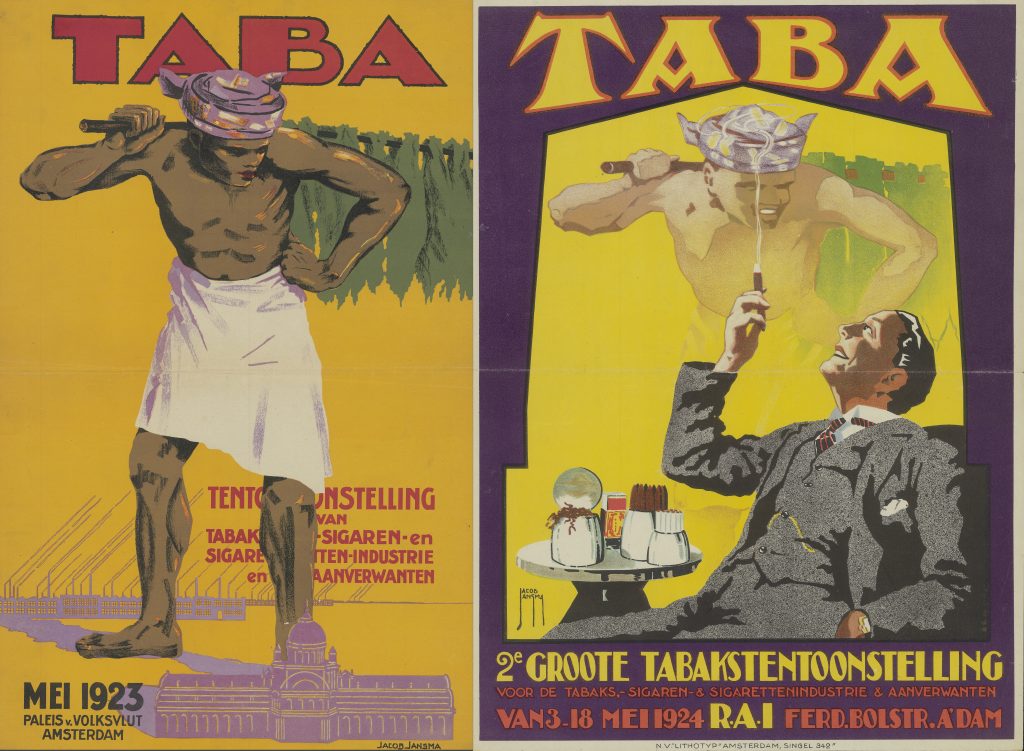

We even found a third Dutch sheet music cover in our collection —from the same period— which promotes tobacco. It is called TABA-Marsch. A rather wealthy and haughty man is enjoying a cigar. His smoker’s paraphernalia is displayed on a side table. In the background, seemingly arising from the cigar smoke, looms a smiling tobacco labourer or koelie (coolie). The strong labourer carries a stick of tobacco leaves on his shoulder.

It is a beautiful illustration but it strongly suggests the offensive colonial attitude of the Dutch at that time. The island archipelago of the Dutch East Indies (a Dutch colony, now Indonesia) was a society with huge class differences. The indigenous people and imported workforces had to live in neighbourhoods or kampongs divided and based on ethnicity. The coolies working on the plantations were contract labourers. Their rights, and more importantly all kinds of restrictions were established with the Koelie Ordonnantie (Coolie Ordinance) of 1880.

The penal sanction was the most outrageous part of this Ordinance which stipulated that a plantation-owner could punish his coolies in any manner he saw fit, including fines. The reasons for punishing a coolie could be many, including laziness, insolence or desertion. Whipping thus became a common practice on the tobacco plantations of the Dutch East Indies. These type of sanctions were gradually abolished from 1931 onwards.

TABA was a large tobacco exhibition (1923 and 1924) held in Amsterdam. Jacob Jansma created the posters for it and used the same illustration for the sheet music. The reason for this exhibition was the malaise in the tobacco economy in Holland.

During the First World War the Dutch economy had blossomed. Thanks to the Dutch neutrality and without foreign competition, the tobacco industry and trade had free rein on the national and international markets. But after WW1, the sudden decline in export and the foreign competition led to massive dismissals in Holland and in the colonies. Hence the TABA exhibitions in order to crank up the business.

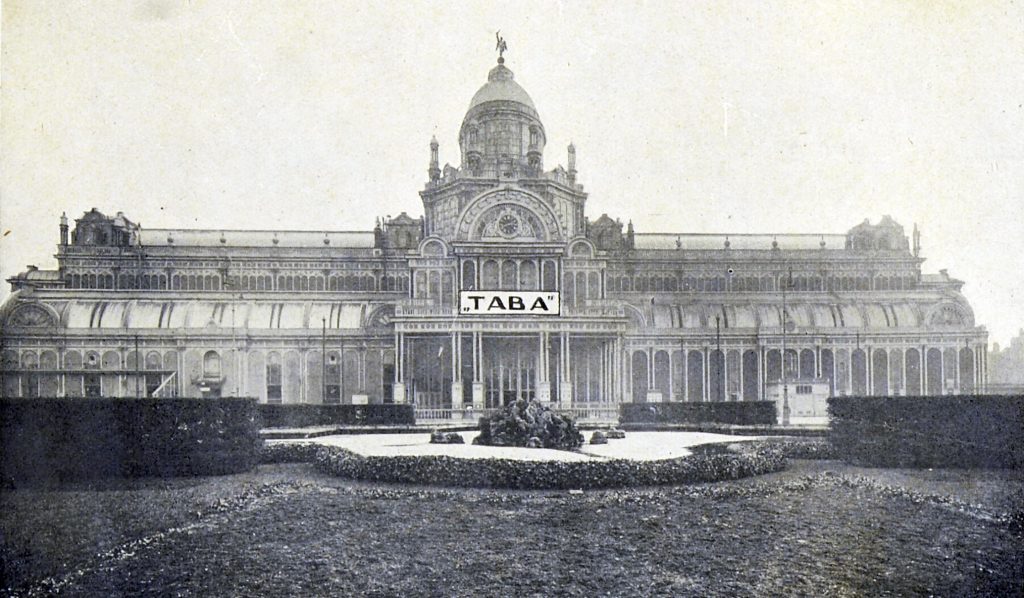

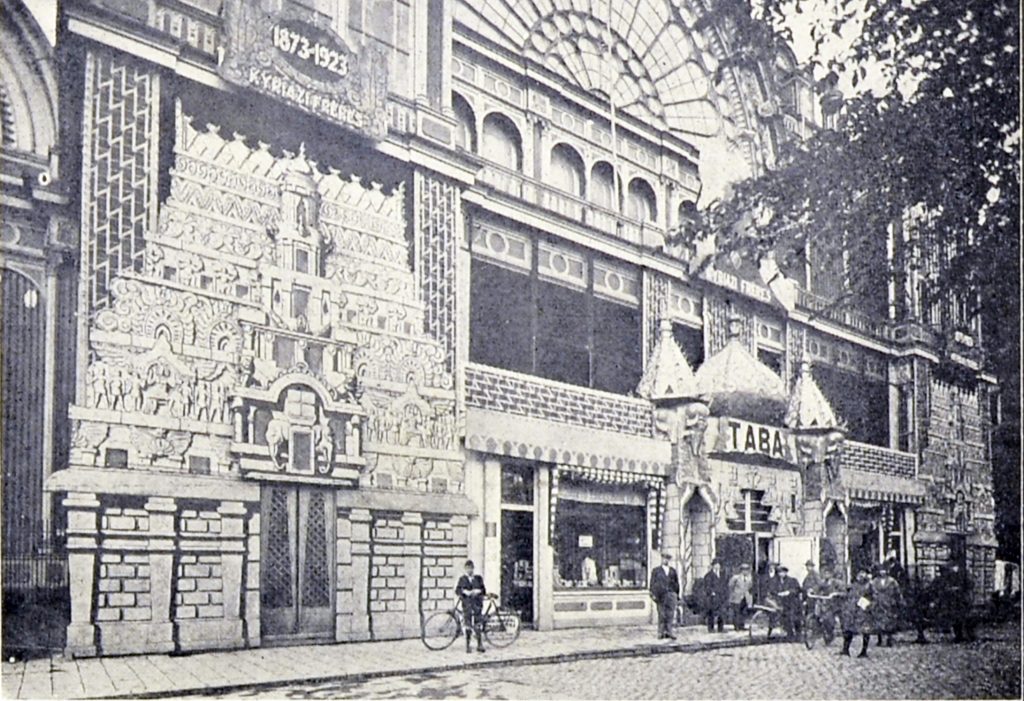

The 1923 TABA exhibition took place in a large hall, the Paleis voor Volksvlijt (Palace for Popular Industriousness). Inspired by the Crystal Palace in London, it was made of glass and cast iron and it was likewise destroyed by fire much to the chagrin of the Amsterdammers.

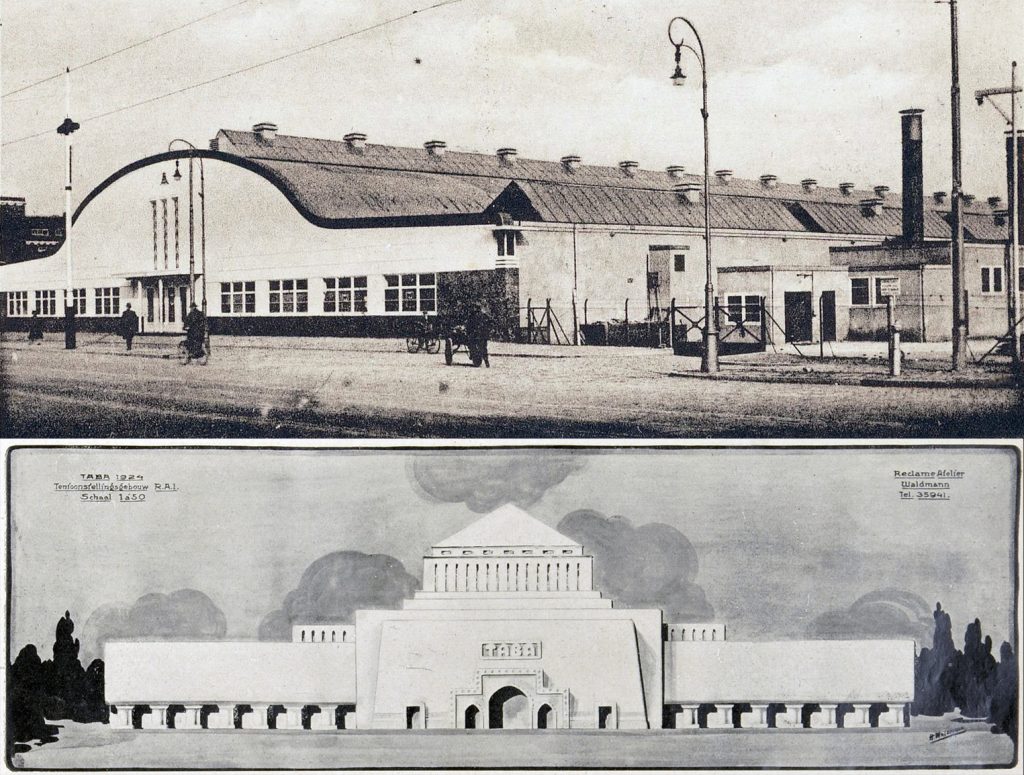

In 1924 TABA moved to the RAI, a newly built ‘state of the art’ exhibition hall, but this event counted significantly less visitors.

In 1925 a new attempt was made to move TABA back to the stylish Paleis voor Huisvlijt and to create an even greater event with lots of foreign exhibitors, but the enterprise failed before it even started.

Enough now for this post. Let’s move on to Tobacco Road with the Winter brothers. YEAH!