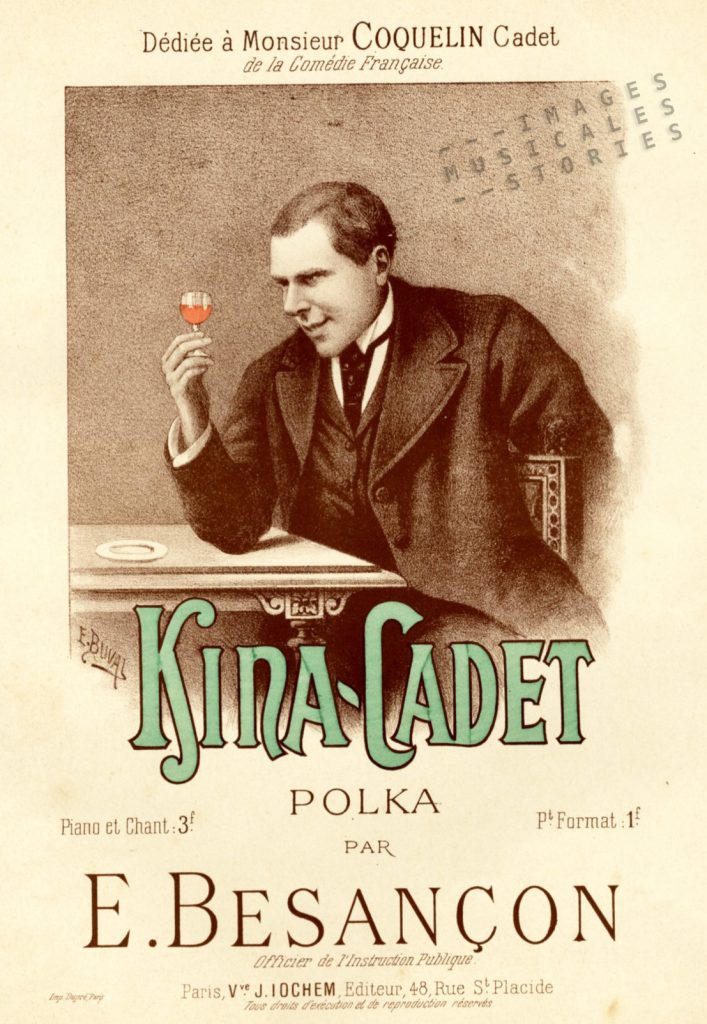

The man looking rather ominously at his bitter is popular French actor, Ernest Coquelin (1848–1909). His older brother was also an actor, and that’s why Ernest was nicknamed Coquelin Cadet. The sheet music title proves that Coquelin Cadet —probably in an effort to turn his notoriety into money— lent his name to a beverage named Kina-Cadet. These quinine-based wines, or kina’s, were very popular during the fin de siècle as aperitif or as ‘medicinal’ wines.

The source of quinine is the bark of the cinchona or fever tree, native to the Andean tropical forests. The Quechua people grounded the cinchona bark into a fine powder that they used as a remedy against fever. The Jesuits in colonial Peru, having learned of this local use, introduced cinchona bark in Europe as a powerful antimalarial around 1640. Although according to some it was the wife of a Spanish viceroy to Peru, the countess of Chinchon, who brought it back with her after being cured of a fever by her Peruvian maid. In 1820 two French pharmacists isolated the active chemical compound, an alkaloid that they called quinine. From then on pure extracted quinine was used to treat malaria instead of the bark.

The source of quinine is the bark of the cinchona or fever tree, native to the Andean tropical forests. The Quechua people grounded the cinchona bark into a fine powder that they used as a remedy against fever. The Jesuits in colonial Peru, having learned of this local use, introduced cinchona bark in Europe as a powerful antimalarial around 1640. Although according to some it was the wife of a Spanish viceroy to Peru, the countess of Chinchon, who brought it back with her after being cured of a fever by her Peruvian maid. In 1820 two French pharmacists isolated the active chemical compound, an alkaloid that they called quinine. From then on pure extracted quinine was used to treat malaria instead of the bark.

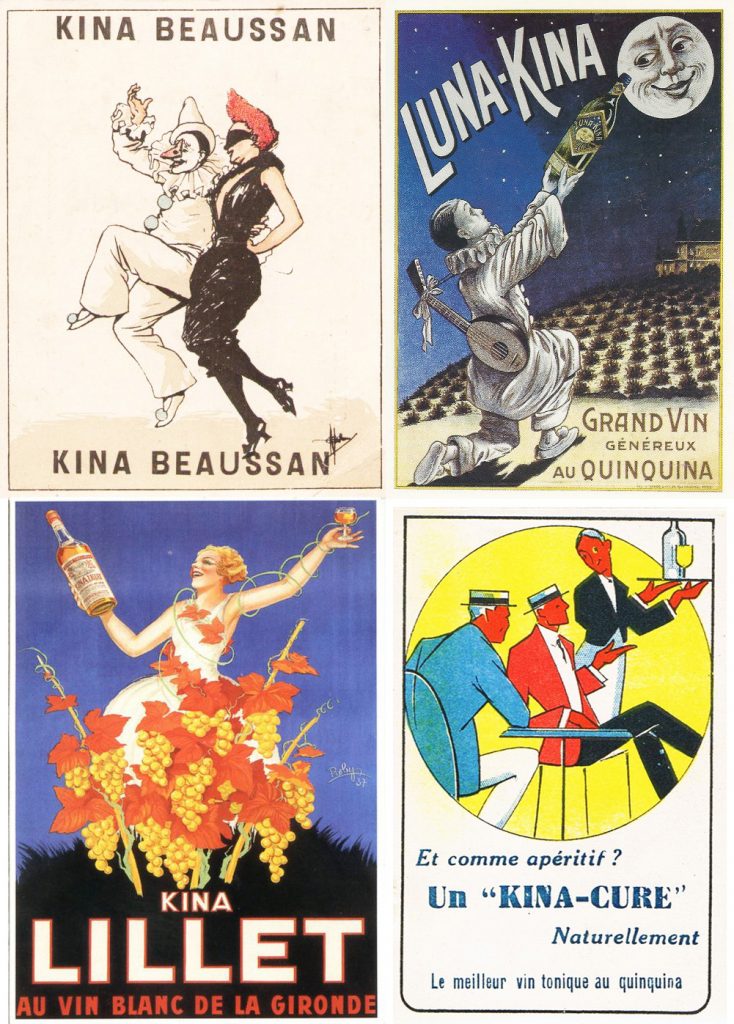

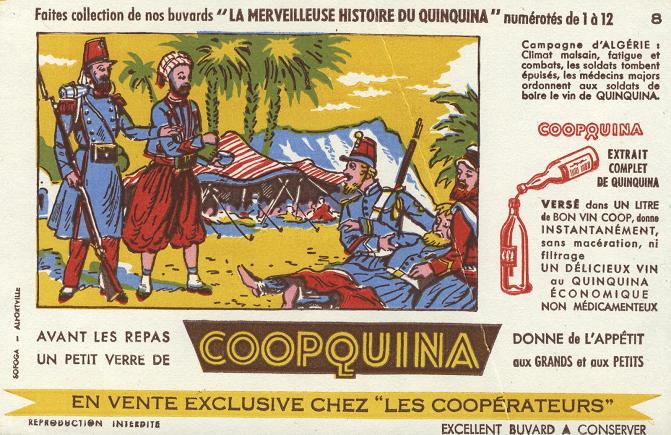

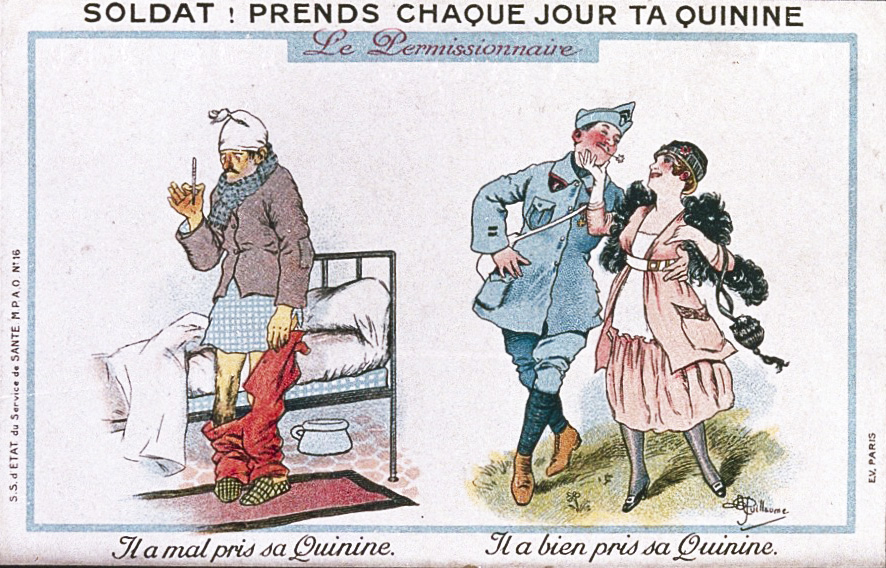

As a result of 19th century European colonialism, the demand in quinine rose for colonials and soldiers stationed in malaria-infested areas. To make the bitter quinine more palatable it was mixed into a liquid, commonly gin (for the British). Or it was blended with fortified wine, herbs and spices (pour les Français). And of course today quinine still is a flavouring of tonic water, bitter lemon, vermouth, and cocktails.

According to Dubonnet, the French government even held a contest in the 1840s, looking for a new drink that contained quinine and also could be enjoyed by the troops.

According to Dubonnet, the French government even held a contest in the 1840s, looking for a new drink that contained quinine and also could be enjoyed by the troops.

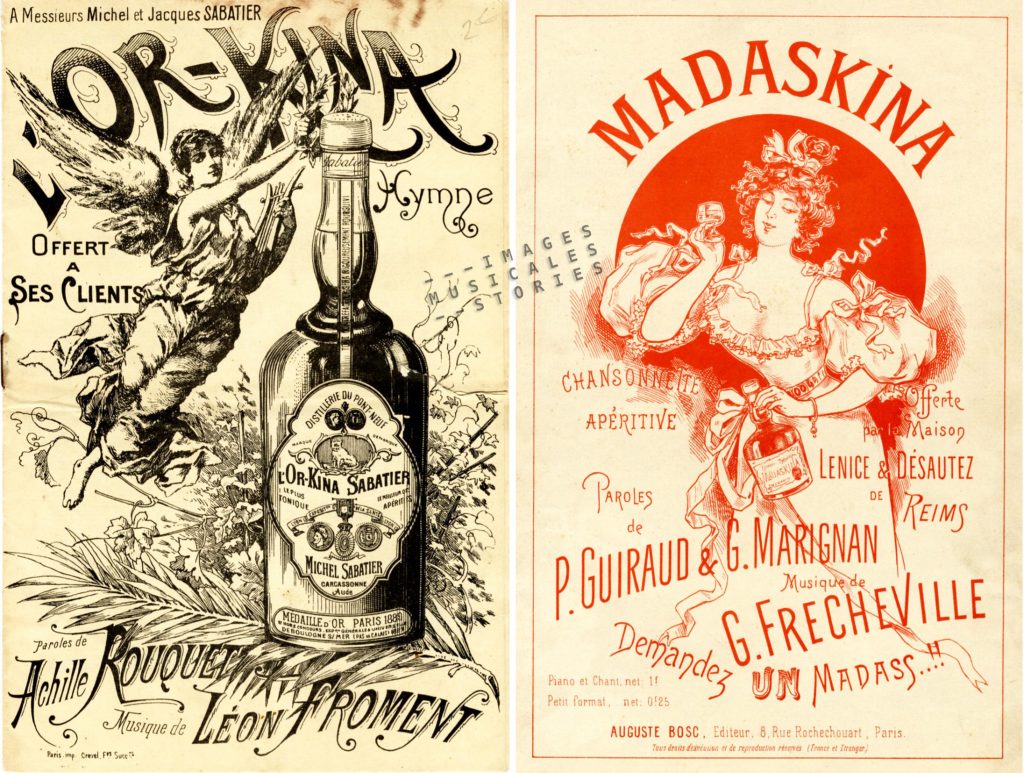

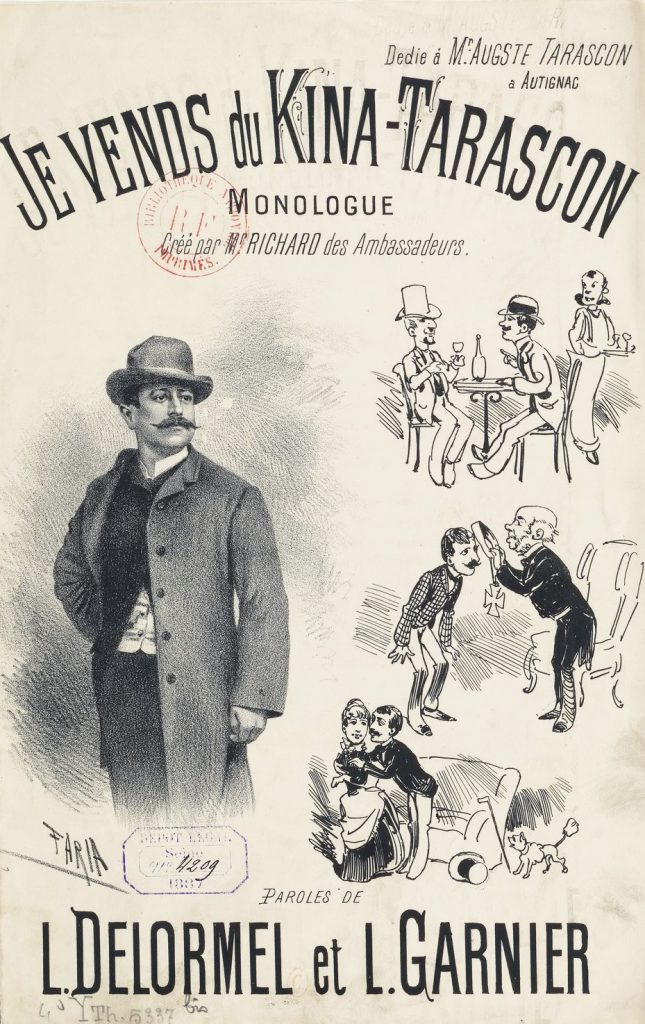

At the end of the 19th century the number of different quinine wines on the market exploded. To our delight, this commercial competition gave rise to songs and sheet music to promote some of these Kina brands.

These quinine wines were not only sold in liquor stores but also in pharmacies. It was recommended to take at least one glass a day, and even a spoonful for children. The Kina tonic wines supposedly had invigorating effects…

The publicity above (for Marsala Kina) was illustrated by Ballester using an ephemeral sculpture technique which we explained in an earlier post. Vouched for by a doctor Valiès, the advertisement tried to convince the potential user that kina wines were indeed medicinal. The fortified wine was infused with iron salts, quinine, kola, coca, tannins and iodine. It could be used against all kinds of diseases and was infallible to combat chlorosis, anaemia, tuberculosis, rheumatism, pale colours, states of languor and weight loss due to undernutrition, overwork, etc.

The publicity above (for Marsala Kina) was illustrated by Ballester using an ephemeral sculpture technique which we explained in an earlier post. Vouched for by a doctor Valiès, the advertisement tried to convince the potential user that kina wines were indeed medicinal. The fortified wine was infused with iron salts, quinine, kola, coca, tannins and iodine. It could be used against all kinds of diseases and was infallible to combat chlorosis, anaemia, tuberculosis, rheumatism, pale colours, states of languor and weight loss due to undernutrition, overwork, etc.

And doctor Valiès spared no expense to sell his wine…

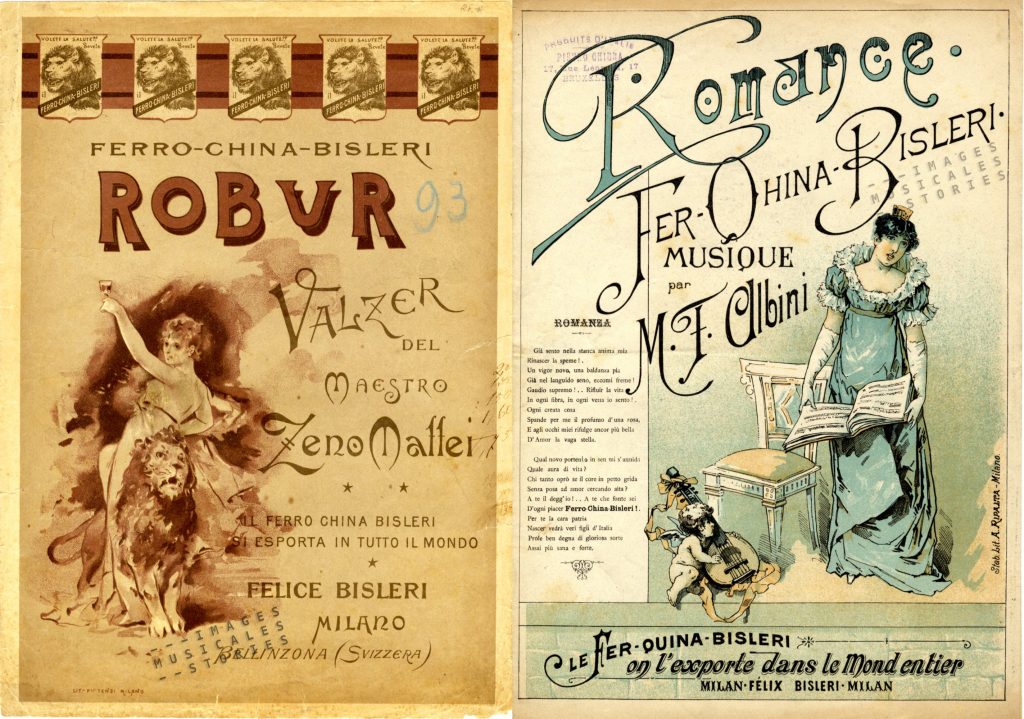

We have found in our collection two other Kina covers which promote an Italian amaro: Ferro-China-Bisleri.

We have found in our collection two other Kina covers which promote an Italian amaro: Ferro-China-Bisleri.

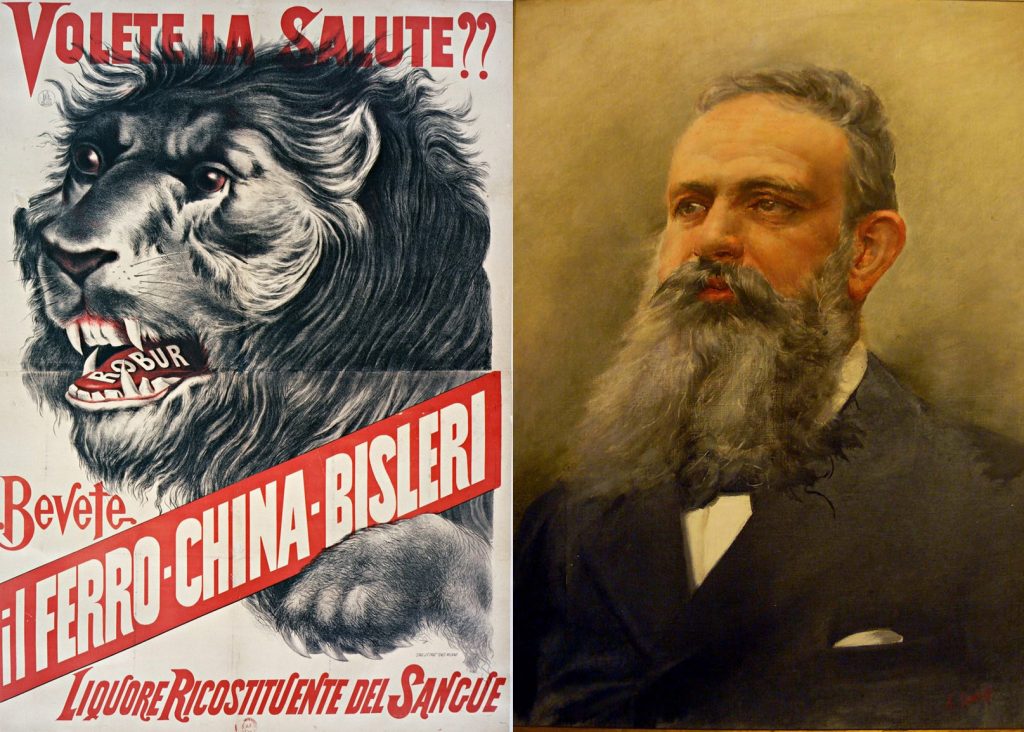

Ferro-China-Bisleri was the first bitter to claim having also infused iron salts within the quinine drink. Its label shows a lion in which mouth one reads ROBUR —signifying force in Latin, and phonetically evoking the roar of a lion. Signore Bisleri himself resembles a lion. He looks very determined and ferocious indeed.

Felice Bisleri had been a freedom fighter under Garibaldi before becoming an inventor and pharmacist. At the tender age of 14, he fled his home to enlist in the Volunteers Corps of Garibaldi. A year later he was decorated with a medal for Military Valour for having distinguished himself in a battle where he continued to fight despite being wounded. It appears that at this young age Bisleri perhaps already drank vigorously from his own Kina wine…

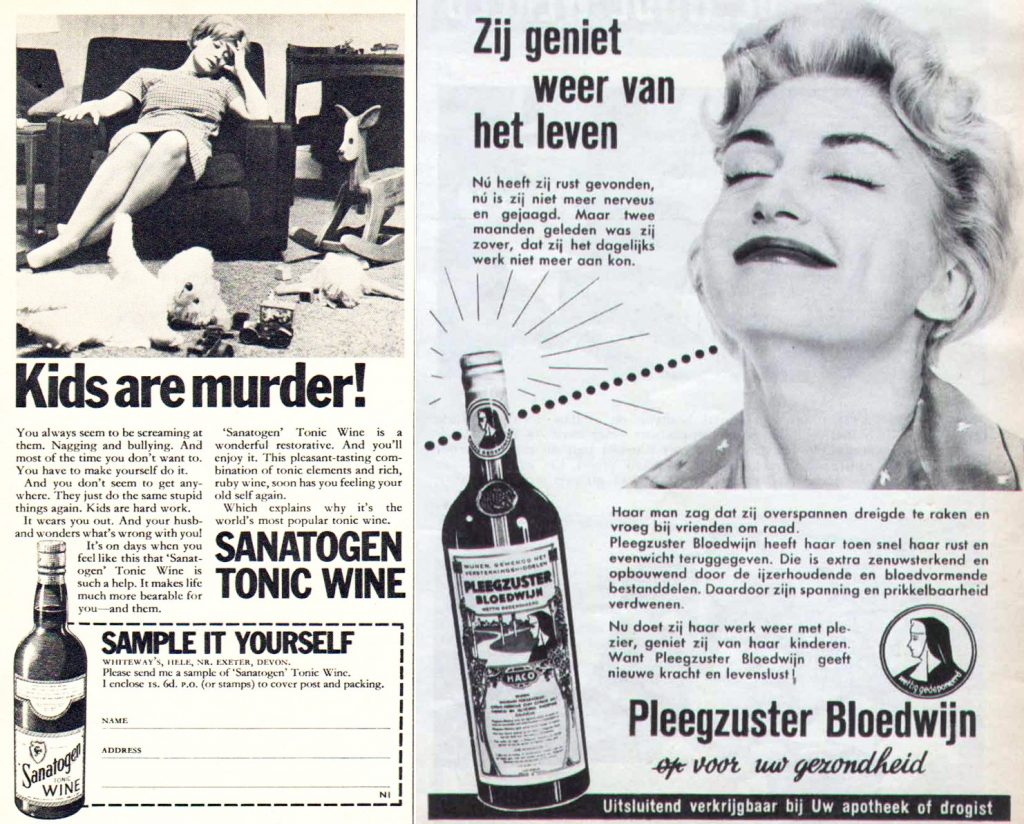

In the sixties and seventies tonic wines knew a revival. Advertisements in women’s magazines and newspapers targeted a new clientele by promising that it was beneficial for ladies.

The publicity claimed that by consuming a few glasses a day of the ‘wonderful restorative’ one could avoid a nervous breakdown. One felt so comfortable and life became suddenly more bearable after drinking this ‘medicine’ with an alcohol percentage of 13.5%.

Dear housewives or mothers, if you can’t cope any more with another day of drudgery, an empty house, doing the dishes and the same old dull household tasks while your husband has all the fun, don’t reach for the booze. Instead listen to Arno with his version of Mother’s Little Helpers and put your feet up.

Our attentive reader Petr informed us that the portrait of Coquelin Cadet by Buval resembles the one drawn by Tamagno for a Kina-Cadet publicity poster. Who copied (or inspired) whom?

(image from http://www.kulturpool.at/plugins/kulturpool/showitem.action?itemId=4295510844&kupoContext=default)

A votre santé … et à celle de Mr Augste (sic) Tarascon : les coquilles d’imprimerie ou fautes d’orthographe ne datent pas d’hier et les partitions n’y échappent pas, on en relève de nombreuses. Ce qui n’enlève rien à l’intérêt de nos illustrations favorites.

Etienne.