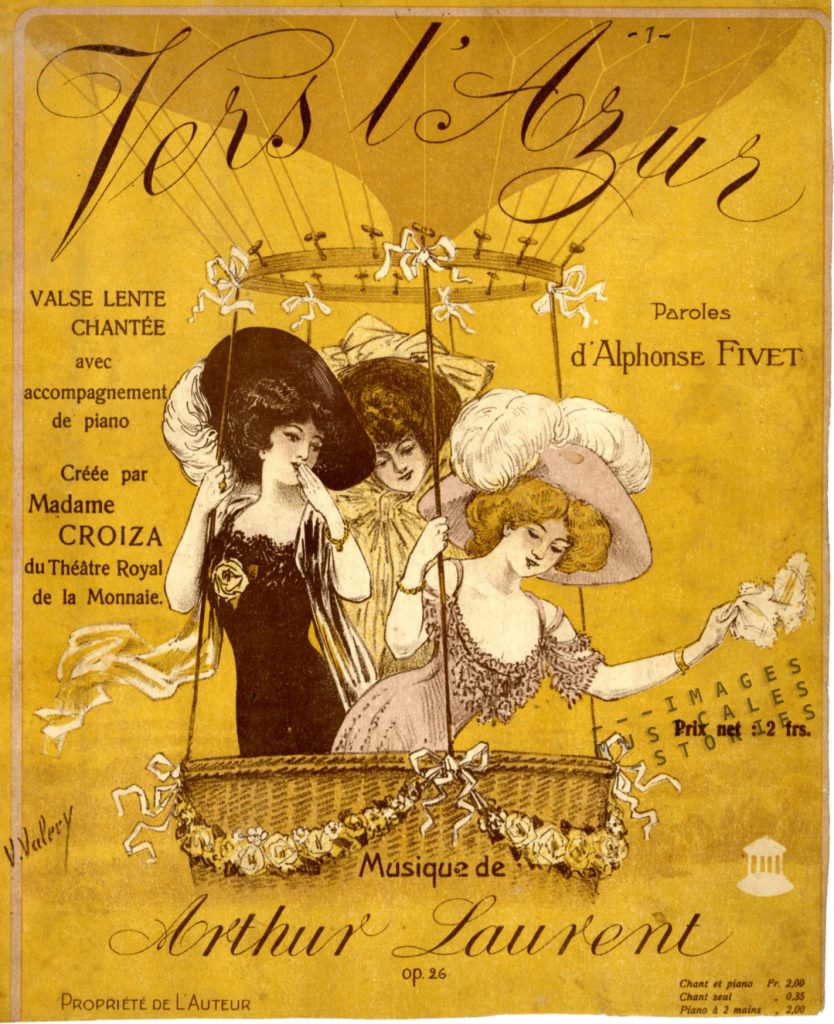

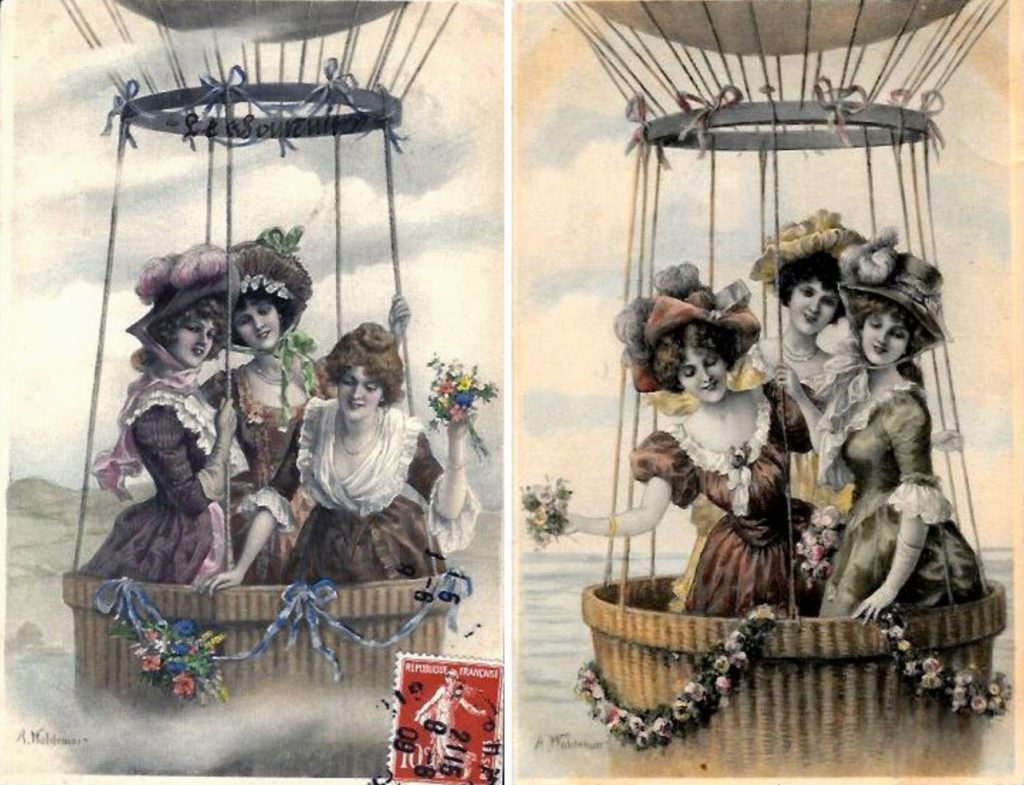

There’s no shame in recycling a good idea, the Belgian illustrator Valéry must have thought. We’ve found just the postcards that most likely inspired his imagination for drawing the cover of the Vers l’Azur waltz…

In 1784, one year after the first free flight with human passengers, Joseph Montgolfier launched a tethered balloon in Paris, which went higher than the highest building. Three ladies formed the gallant crew: Marquise de Montalembert, Countess Podenas, and Mademoiselle de Lagarde. They were the first three women to make a voyage into the sky. From then on, for over a century, women were piloting balloons.

But after the Franco-Prussian war, the role of women in French society became more than ever restricted to being a wife and mother. Flying aerostats wasn’t a sport for them and was claimed as an exclusive male activity. Nevertheless some female aficionados of the sport persisted, albeit discredited by most of their male counterparts. One of them was Camille du Gast, a Belle Epoque singer and daredevil sportswoman who made balloon trips at the end of the 19th century.

The real inspiration for the three female aeronautics on the post cards was the French Marie Surcouf and her friends. The same year one of the postcards was stamped, they had founded the first female aeronautical club in 1909. Marie’s father was an industrialist who owned a factory for making hot air balloons. She married Edouard Surcouf, an engineer and collaborator of her father. He later took over his father in law’s firm and started building large air ships. Marie herself was also an aeronautics enthusiast. For years she urged aero clubs to grant women the same rights as the male pilots. Unsuccessful in her quest, she decided to found Stella, a female aeronautical club in 1909. The club promoted flying in hot air balloons for women, which led to the recognition of women as competent aeronautic professionals.

The French newspaper Le Figaro of June 17th, 1909 gives us an impression of the first flowered air festival organised by Les Stelliennes, the female members of Stella. From a male perspective, sure enough:

“In the park on the slopes of St. Cloud, a highly elegant crowd of guests arrived. Soon, the park, already adorned by greenery and baskets, became one lovely garland of women dressed in white, pink, mauve and blue. The six balloons, deliciously decorated with flowers of which they bore the name, swayed captive waiting for the departure … Among the passengers were a lot of newcomers, and their little hearts started to beat very fast because of a sudden gust of wind; but they were still very skilful, very brave, and not one, in spite of the anxieties expressed by some of their friends, did give up the aerial excursion.

The graceful Stelliennes delightedly scattered flowers on the audience. The first balloon to leave in a cloud of scented petals, was the balloon called ‘Les Bleuets’ (The Cornflowers). It carried on board three ladies. One of them was Mrs Surcouf, president of the Stella and pilot of the balloon.”

Although the passengers in the other five balloons were women, they were piloted by men, because at that time only Mme Surcouf was a qualified pilot.

Stella clearly had a feminist mark: men were accepted as members but they were excluded from the management of the club.

A picture of the board of directors shows five bold ladies, some of them with a huge nest of flowers on their lavishly decorated hat. They also look very well-to-do, which of course they were, just like all the members. A lot of them belonged to the aristocracy. Amongst them was the wife of Louis Blériot, famous for the first air-plane flight across the English Channel.

Although being feminists, the members of Stella also enjoyed very ladylike things. They organised artistic lyrical evenings or tea parties called Stella-Thé’s. The Stelliennes also embroidered a flag for the military aviation. It was solemnly handed over in 1912 when the first five squadrons were created to form the French Air Force (the oldest air force in the world).

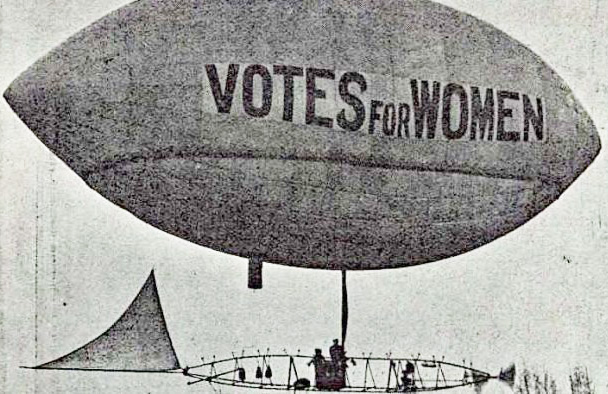

The Stelliennes didn’t go as far as the Australian-born Muriel Matters. In 1909 —the same year Stella was founded— Muriel took to the skies in an airship and scattered campaign leaflets over London, demanding Votes for Women.

Stella stopped its activities with the First World War. It would take until 1971 before another French association of women pilots was founded.

In the sixties, Marilyn and Florence made a musical attempt at female ballooning, together with the other aeronautics of the 5th Dimension. Much to (y)our delight!

This article is dedicated to Zaza, if not a feminist (yet) at least the most beautiful baby in the world.