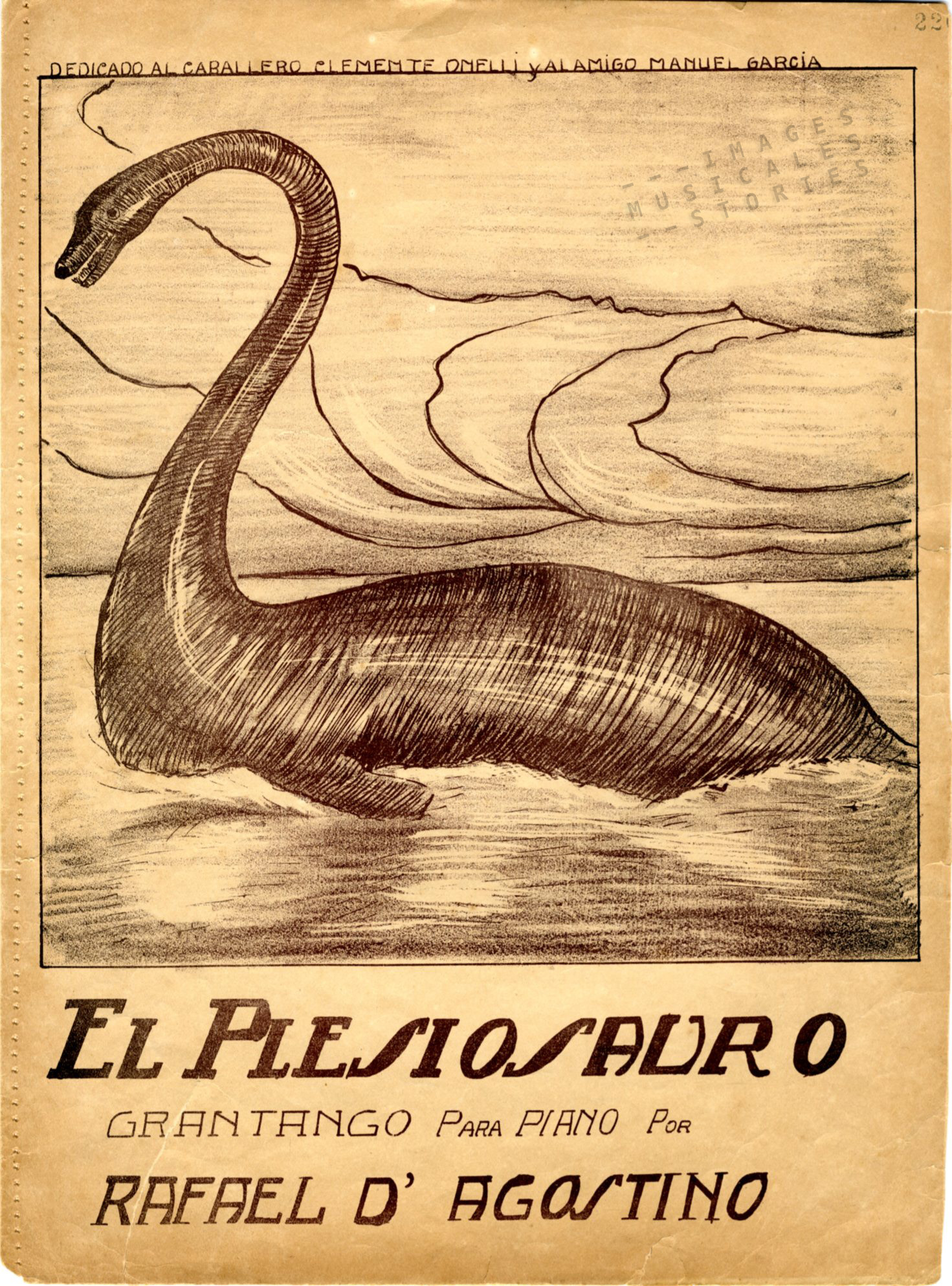

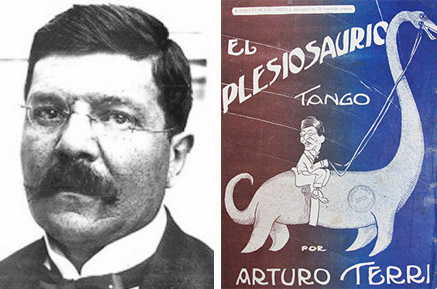

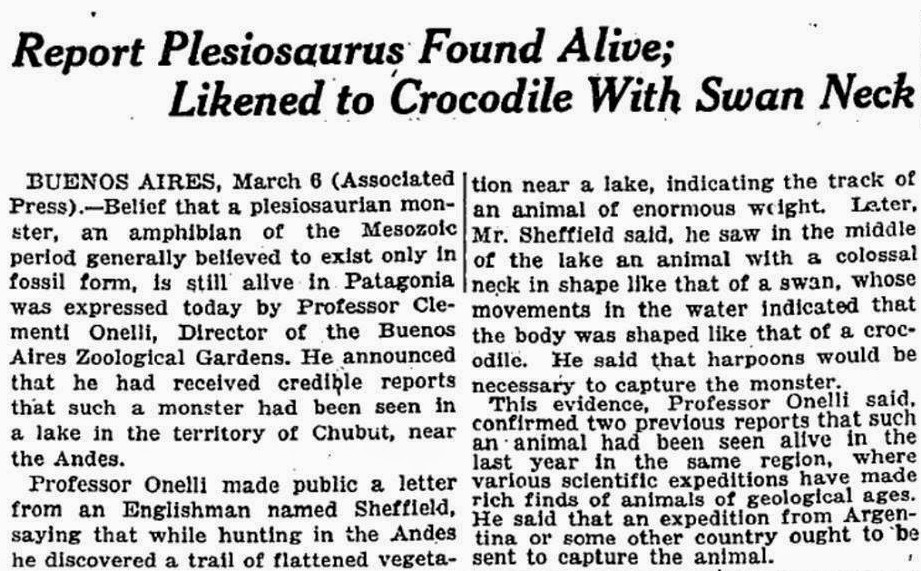

The tango ‘El Plesiosauro’ was composed by Rafael D’Agostino and dedicated to Clemente Onelli (1864-1924), the Italian-born director of the Buenos Aires zoo. In 1922 a letter informed Onelli that an enormous animal had been spotted in a Patagonian lake. It had a huge neck like a swan, moved like a crocodile and left traces of large footprints. This was no doubt ample proof of a surviving specimen of the plesiosaurs, an order extinct at the end of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 66 million years ago.

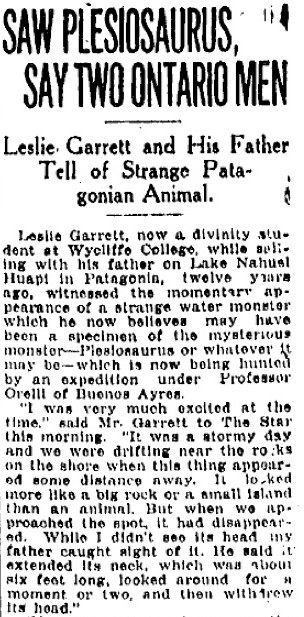

Onelli, a palaeontologist, hoped to find a new specimen for his zoo and arranged an expedition. To prove his point he had published accounts of other sightings well into the previous century. His case was backed by a Canadian student in divinity and his father who wanted their fifteen minutes of fame. They reported witnessing the Patagonian monster twelve years earlier, in 1910.

At the request of the Argentine Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, the Argentinian Minister of the Interior prohibited the capture of the beast. Onelli protested heavily against this decision in the ‘name of science’ and the expedition, armed with elephant guns and dynamite, plunged into the wilderness. Onelli himself did not participate because of health problems. The quest for the beast got worldwide media attention, such as in this article of The New York Times.

The expedition was even mentioned in an article of the Scientific American, titled ‘Is the Argentine Plesiosaurus a Fake or a Scientific Marvel?’. The author concluded ironically that if the plesiosaur ever existed, it appeared to have fled elsewhere. Needless to say that the expedition was fruitless. This lead to much mockery and merriment as witnessed in this photo of the plesiosaur carnival float in 1923.

Plesiosaurs were large aquatic reptiles that lived at the same time as the dinosaurs. The first two plesiosaur skeletons were found by Mary Anning (1799-1847) an English fossil collector and amateur palaeontologist. Being a woman she never got the recognition she deserved during her lifetime. Mary came from a working class family in Lyme Regis. She never went to school but could read and write a little, and she drew rather well. Her father taught her how to find fossils on the beach and sell them to tourists. Mary hunted on the beaches and cliffs between Lyme Regis and Charmouth, part of the Jurassic Coast as it is called now.

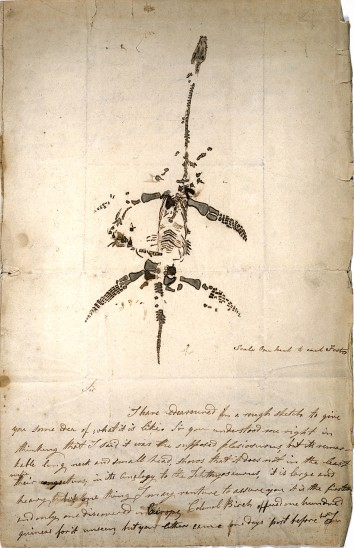

When she found a special fossil she would send her drawing of it to potential buyers. One of Mary’s major discoveries was what we now call the plesiosaur. She found its skeleton in 1823 and made the following sketch for her fellow scientists and for possible buyers.

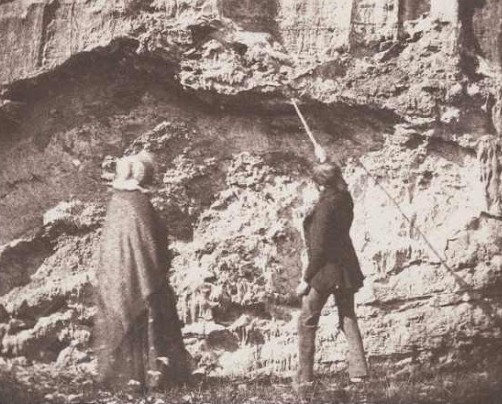

According to a science blog on the Guardian’s website the two persons on the photo below could well be Mary and her lifelong friend Henri de la Beche, a geologist. Although the supposition lacks evidence, it provides a nice picture to end our palaeontological post.

According to a science blog on the Guardian’s website the two persons on the photo below could well be Mary and her lifelong friend Henri de la Beche, a geologist. Although the supposition lacks evidence, it provides a nice picture to end our palaeontological post.

Further reading: Austin Whittall, Patagonian Monsters

De bladmuziek archeologen uit Gent hebben weer mooi werk afgeleverd !