‘Gabor Steiner! I like this man. How grateful all Wiener should be to him! He alone saves Vienna’s reputation as a theatre town, as the city of music, dance and joy of life’.

Adolf Loos, 1903.

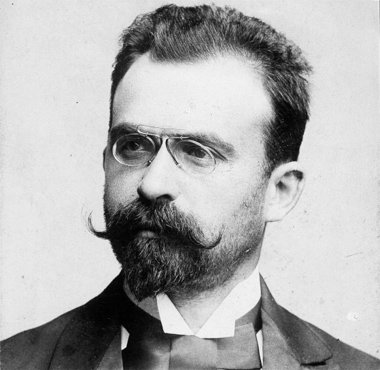

Gabor Steiner (1858-1944), the publisher of ‘Morgen Vielleicht!’ (Maybe Tomorrow!) was born with entertainment in his veins. Since early childhood he was spiritually nourished by artists and composers. His father was a famous Viennese theatre manager. His son’s godfather was the leading Austrian composer Richard Strauss. Amongst the friends of the family were Jacques Offenbach and Johann Strauss, Jr. Well, that is to say, until Johann Strauss’ second wife —thirty years his junior— left her middle-aged husband for Gabor’s brother.

Gabor was a busy bee, always on the lookout for new ways to entertain people. He started working in theatres in Germany before ending back up in Vienna where he founded a concert and theatre agency In 1887. Two years later he began a publishing house to bring out plays and a theatre newspaper. But in 1890 Gabor Steiner had to stop all these enterprises because they proved not profitable.

During a visit to London Gabor witnessed Venice in London, a unique and dazzling spectacle. It was produced by Imre Kiralfy and staged at the Olympia Theatre. Kiralfy replicated the bridges and canals of Venice using machinery, water and electricity. On the gigantic stage no less than 1,400 persons were busy creating an enchanting illusion. Inspired by this splendour

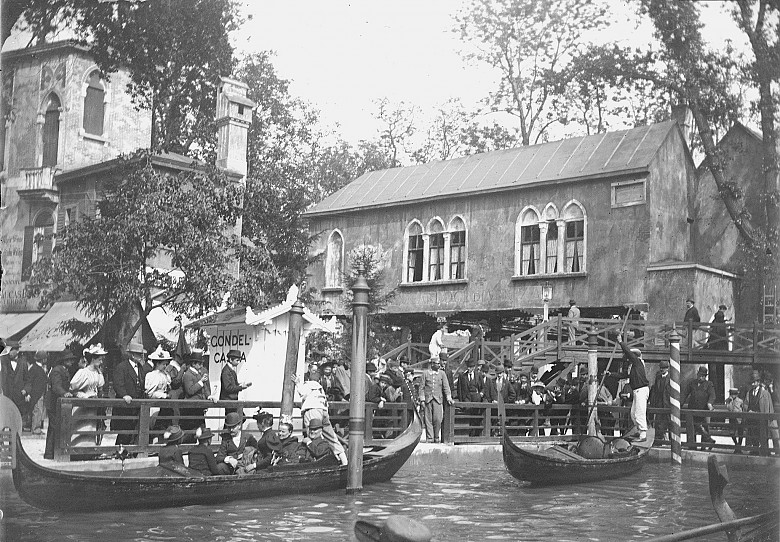

During a visit to London Gabor witnessed Venice in London, a unique and dazzling spectacle. It was produced by Imre Kiralfy and staged at the Olympia Theatre. Kiralfy replicated the bridges and canals of Venice using machinery, water and electricity. On the gigantic stage no less than 1,400 persons were busy creating an enchanting illusion. Inspired by this splendour Gabor leased part of the Wiener Prater, to build his own theatre and entertainment city: Venedig im Wien, which opened in 1895.

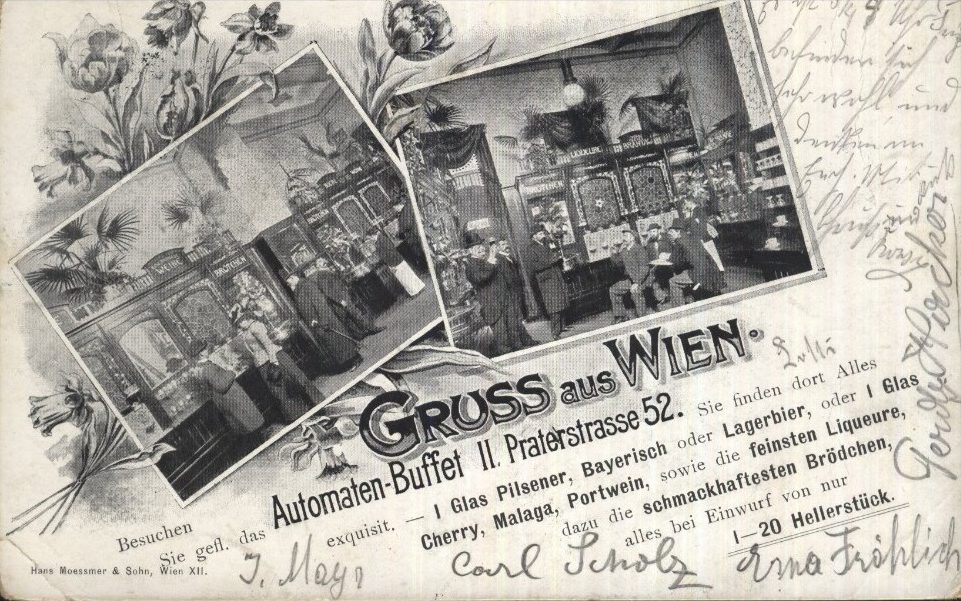

This Viennese version was an ‘artful’ imitation of Venetian buildings and gondolas with navigable channels constructed on an area of the Prater park, roughly half the size of a soccer field. More than 2,000 employees were catering for the visitors. There were shops, restaurants, cafes, a champagne pavilion, a wine tavern and a beer garden. Various stages offered a variety of concerts, Viennese farces, French comedies, operettas, revues, ballets, cabaret and wrestling events. Woo-hoo!

Venedig im Wien became a huge triumph and the extravaganza attracted crowds of people of all classes. The complete Who’s Who of the Viennese operetta performed there for many years.

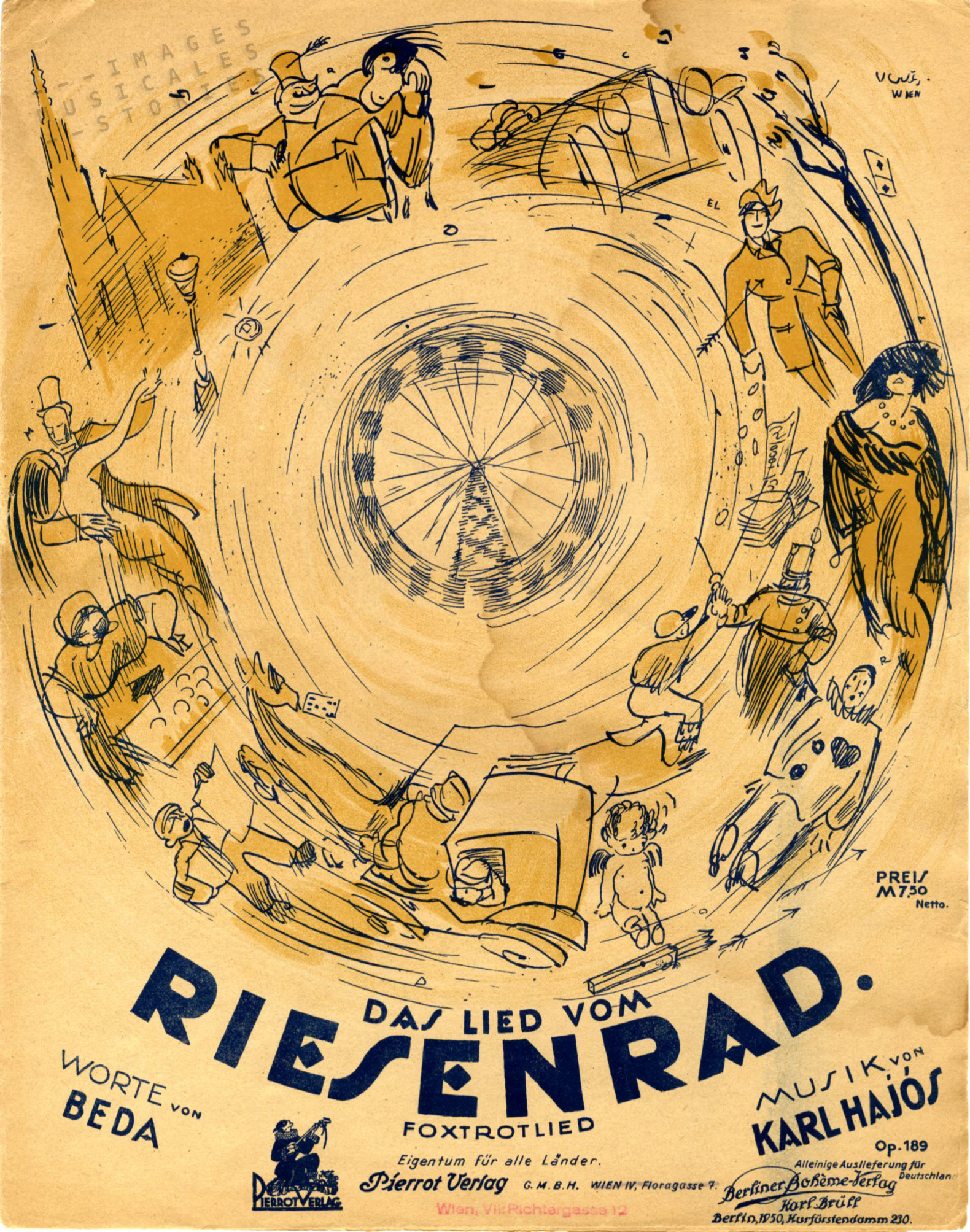

These entrepreneurial excursions didn’t make Gabor lose sight of his golden goose in the Prater park. For fear that the visitors would lose interest, every year Gabor Steiner frantically renewed, expanded or completely remodelled the Venedig theme park. In 1897 he instigated the construction of the iconic giant Riesenrad that you’ve seen in the film The Third Man. Or didn’t you?

It was near this Ferris wheel that in 1987 a lane in the Prater was named in honour of Gabor Steiner. The wheel inspired the fox-trot song Das Lied vom Riesenrad, for which Marcel Vertès —like Gabor Steiner a Hungarian— designed the twirling sheet music cover.

In his constant quest to improve the entertainment park, Gabor filled up a ‘Venetian laguna’ in order to build an open-air theatre for 4,000 spectators. There he treated his public to typical ‘Prater-operettas’ presenting up to 200 dancers in huge ballet scenes.

Later still, in 1901 Steiner demolished the Venetian buildings altogether. In its place he established a new International City, the year after he created a Flower City and in 1903 it became the Electric City.

Later still, in 1901 Steiner demolished the Venetian buildings altogether. In its place he established a new International City, the year after he created a Flower City and in 1903 it became the Electric City.

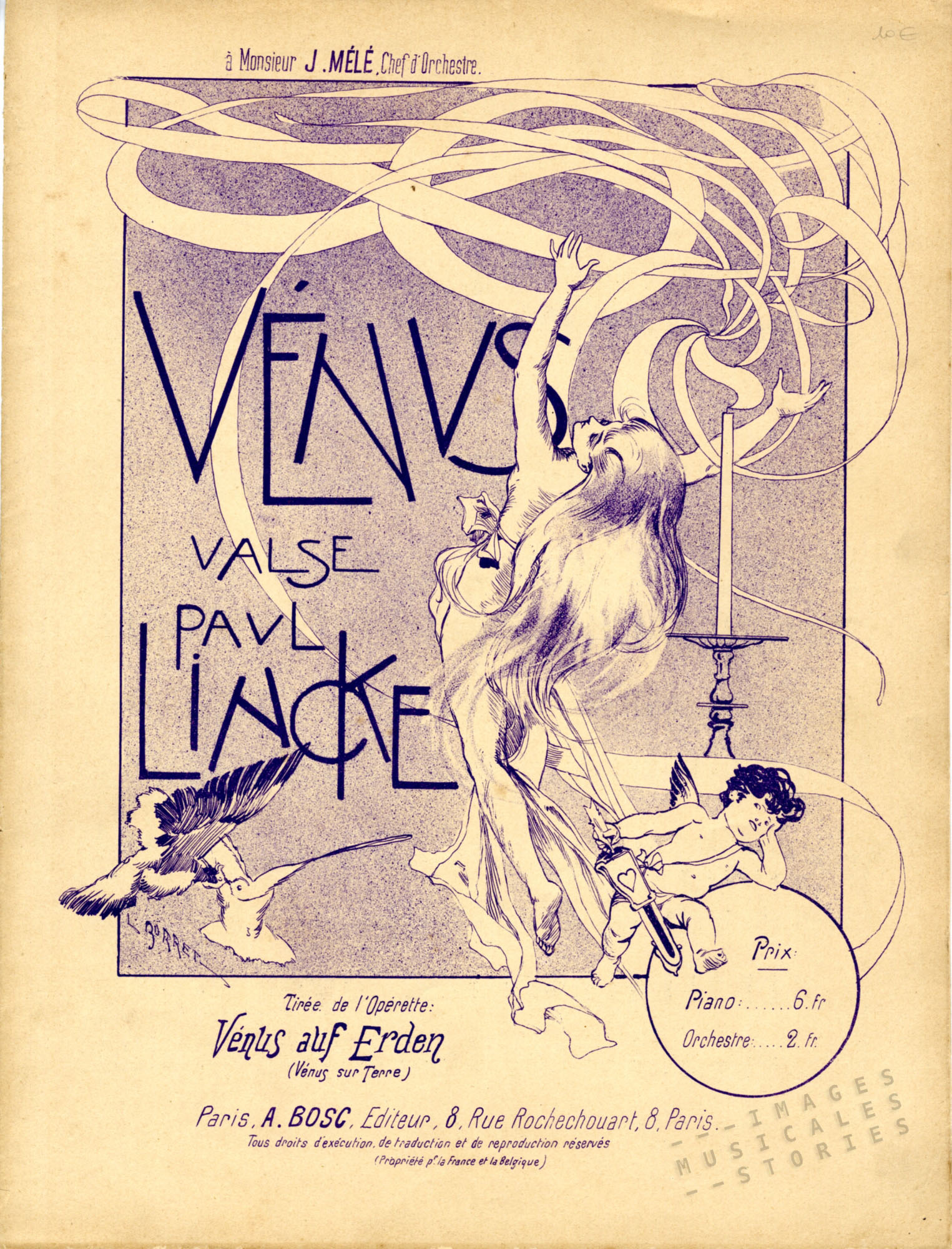

Meanwhile in 1900 Gabor Steiner had acquired the Danzers Orpheum, a theatre in the centre of Vienna. He completely redecorated the place in glitzy neo-Baroque style. The theatre was used as a winter venue (when the park closed) for the Venedig im Wien spectacles. The grand opening was with the operetta Venus auf Erden (Venus on Earth) from Paul Lincke, father of the Berlin operetta.

In 1908 Steiner got into financial difficulties and went bankrupt. For a few years he then tried his luck in managing the Viennese Ronacher theatre. But megalomaniac habits die hard and in 1911, the enormous cost of the theatre’s lavish refurbishing brought him into financial troubles again.

It is now time to focus on Max, the son of Gabor Steiner. Max was a child prodigy, conducting operettas when he was only twelve and composing his first operetta aged fifteen. He would later become known in Hollywood as the father of film music writing the scores for more than 300 films. To mention just a few: Casablanca, King Kong, The Caine Mutiny and Gone with the Wind.

The first time his father went bankrupt, Max moved to live and work in London. But in 1911, when Gabor again run into trouble, he returned to Vienna to help. He took over his father’s theatre and tried to stem the losses, but to no avail. The Ronacher was closed. Max was even imprisoned for a short period. His father had pre-sold a whole-year advertisement in the Ronacher theatre program. As managing director Max was sued for breach of contract.

At the end of that same year 1911 Gabor regained the management of his former amusement Park in the Prater. There he opened an exhibit called the Lilliputstadt (midget city) together with his sister’s son, Leo Singer who had assembled a troupe of performing little people. Lamentably, in the shortest of times, Gabor accumulated more debts and went bankrupt once more. In 1913 he separated from his wife and fled Vienna and his financial problems and he lived for eight years in London, Switzerland and New York.

Abroad, Gabor probably met again with his nephew Leo Singer, who had moved to the United States at the outbreak of the First World War. Years later, in 1938, Singer would provide 124 little people for the Munchkins in The Wizard of Oz.

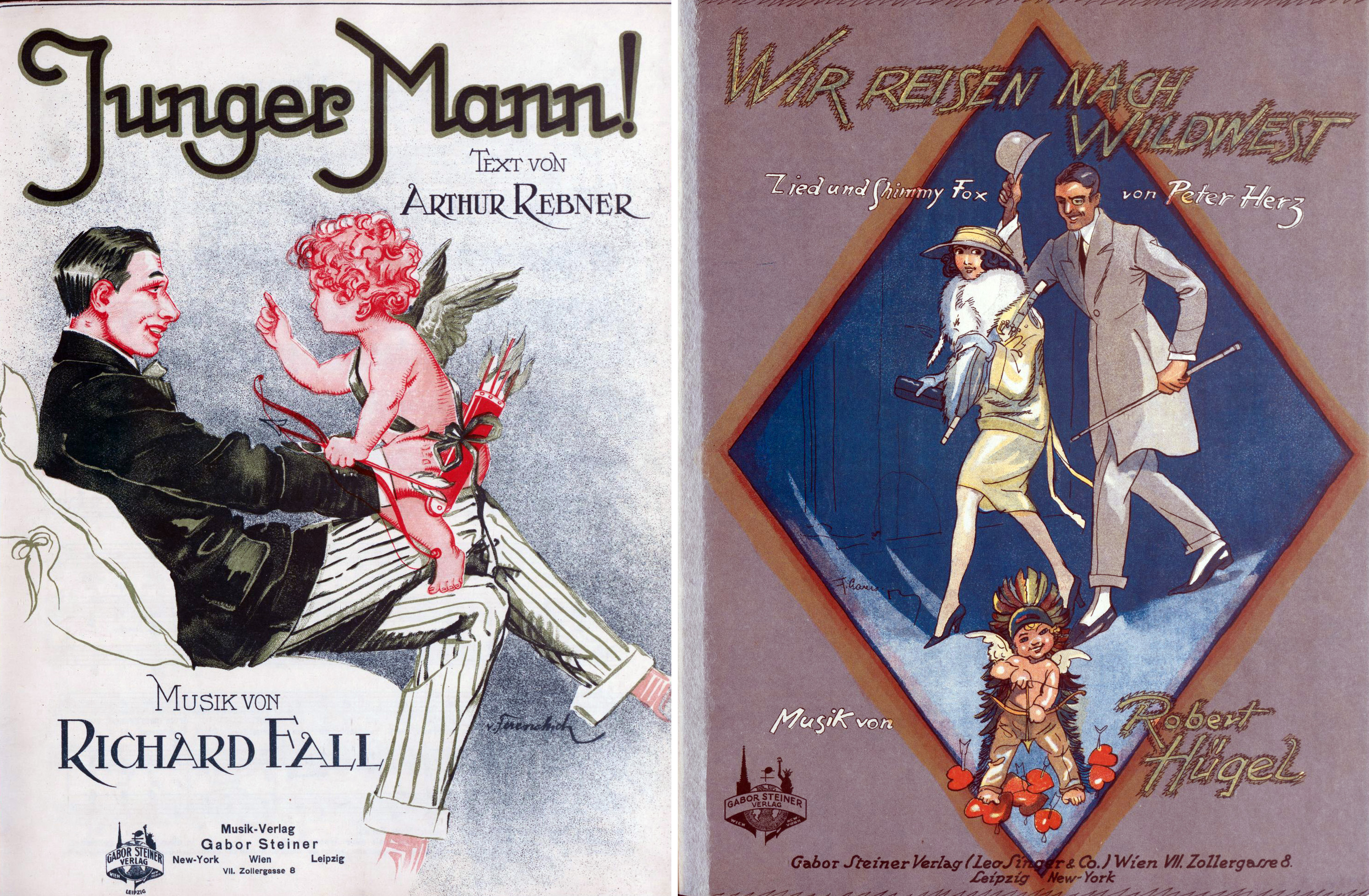

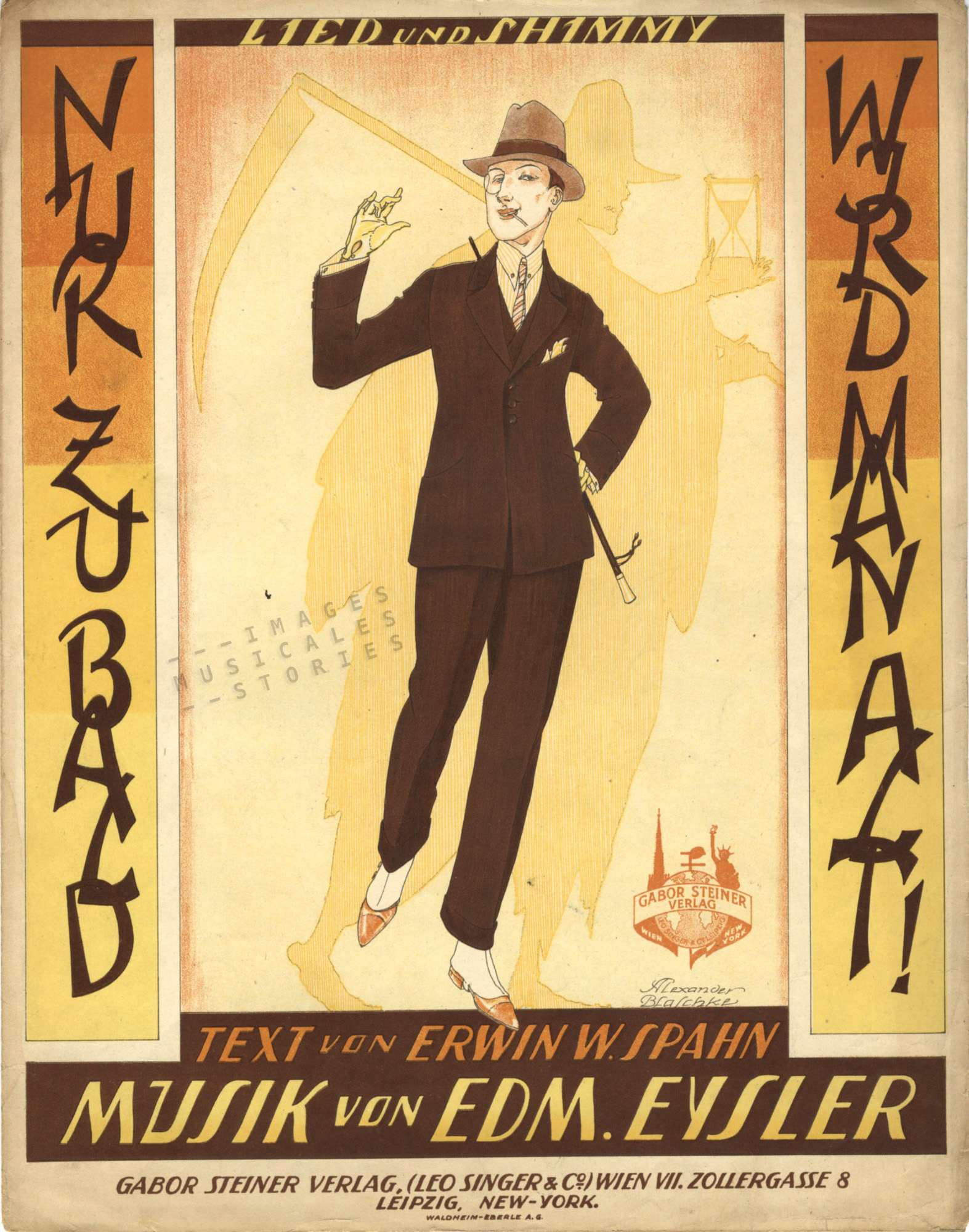

In 1921, after his voluntary exile, Gabor Steiner returned to Vienna. He was now sixty-three and hoped to become a theatre director once more. But it didn’t work out. Instead he started a music publishing house, the Gabor Steiner Verlag, together with Leo Singer who held office in New York and with the financial help of his son Max.

From what we can deduce the publishing venture didn’t last long: the only known sheet music is copyrighted 1923 and early 1924. So far for Gabor’s triumphant comeback!

In 1938 Gabor Steiner, like so many Jewish artists, had to flee from Austria at the age of eighty-one. All his possessions had been taken by the Nazis and he went to live with his son Max, in Hollywood. In Tinseltown he promptly married his son’s secretary. He died in 1944. Perhaps he was more a creator than a businessman but he certainly had led a full life: Nur zu Bald wird man Alt! (*)

* Only to soon you will be old!

Beste Divine en Frank, ik heb dit zeer interessante artikel over Steiner weer opgeslagen, bedankt !