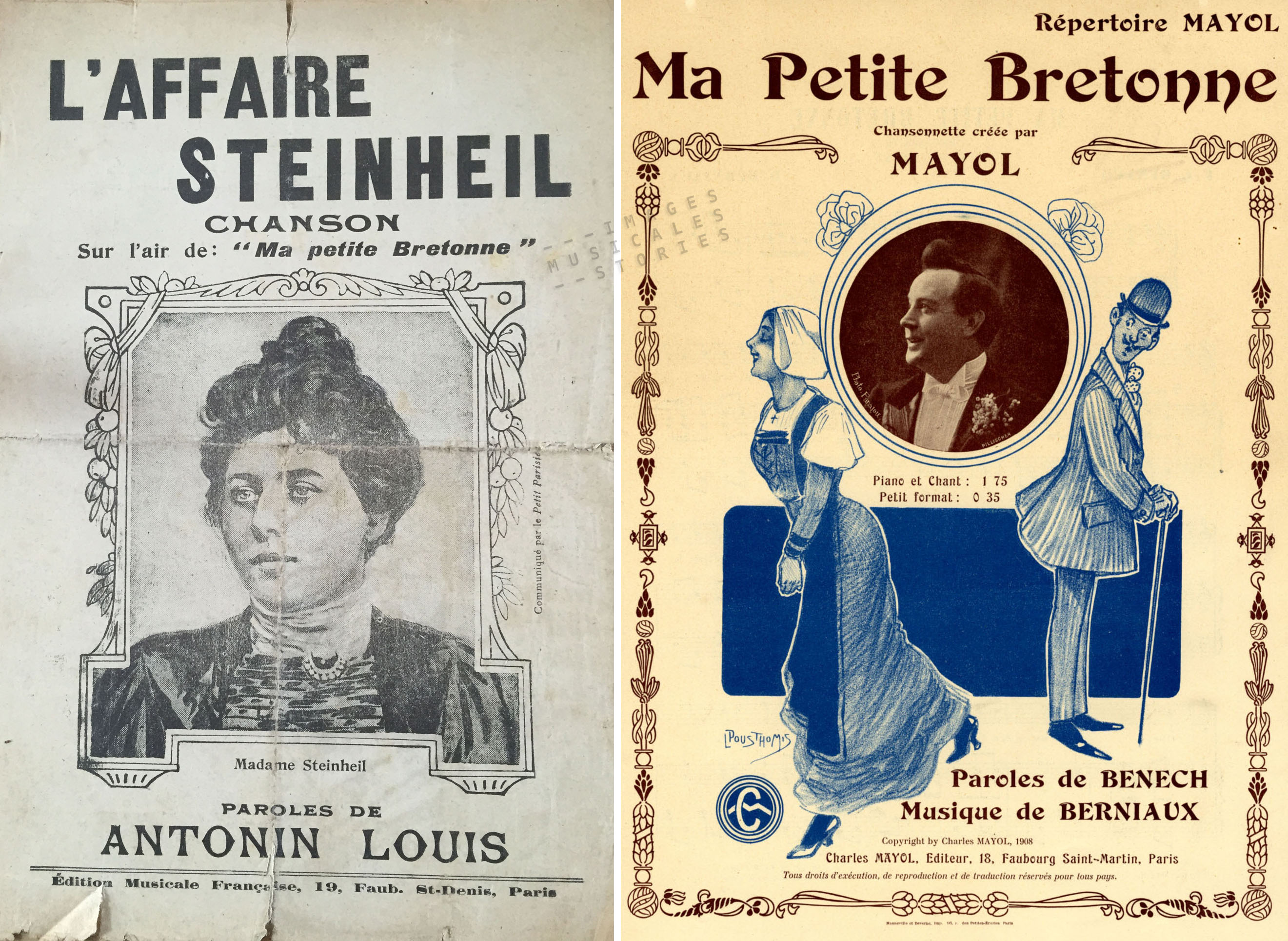

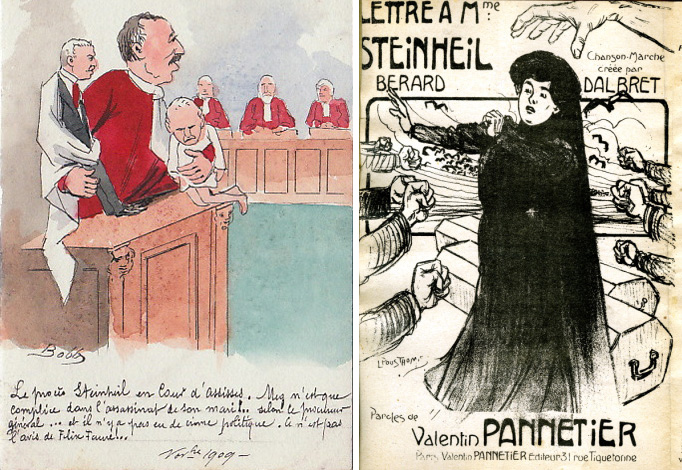

Last week we got a present from our friend Etienne: a tattered leaflet, folded twice to fit in a pocket, ready to hand for an impromptu performance. On the backside of the leaflet are the words for L’Affaire Steinheil. No musical notation was needed as one had to sing it to the tune of a 1907 hit song Ma Petite Bretonne.

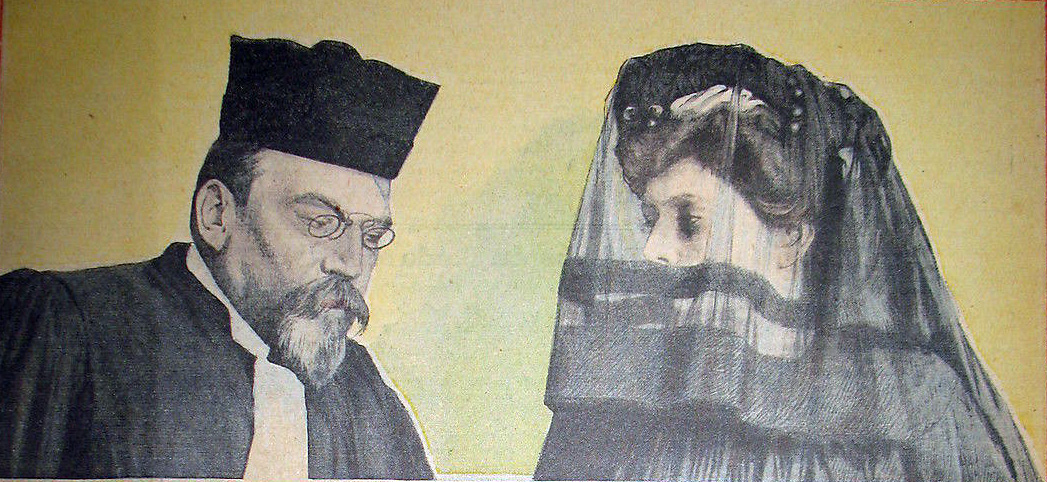

The Madame Steinheil of the cover was born in Alsace in 1869 as Marguerite Japy, the daughter of a rich industrialist.

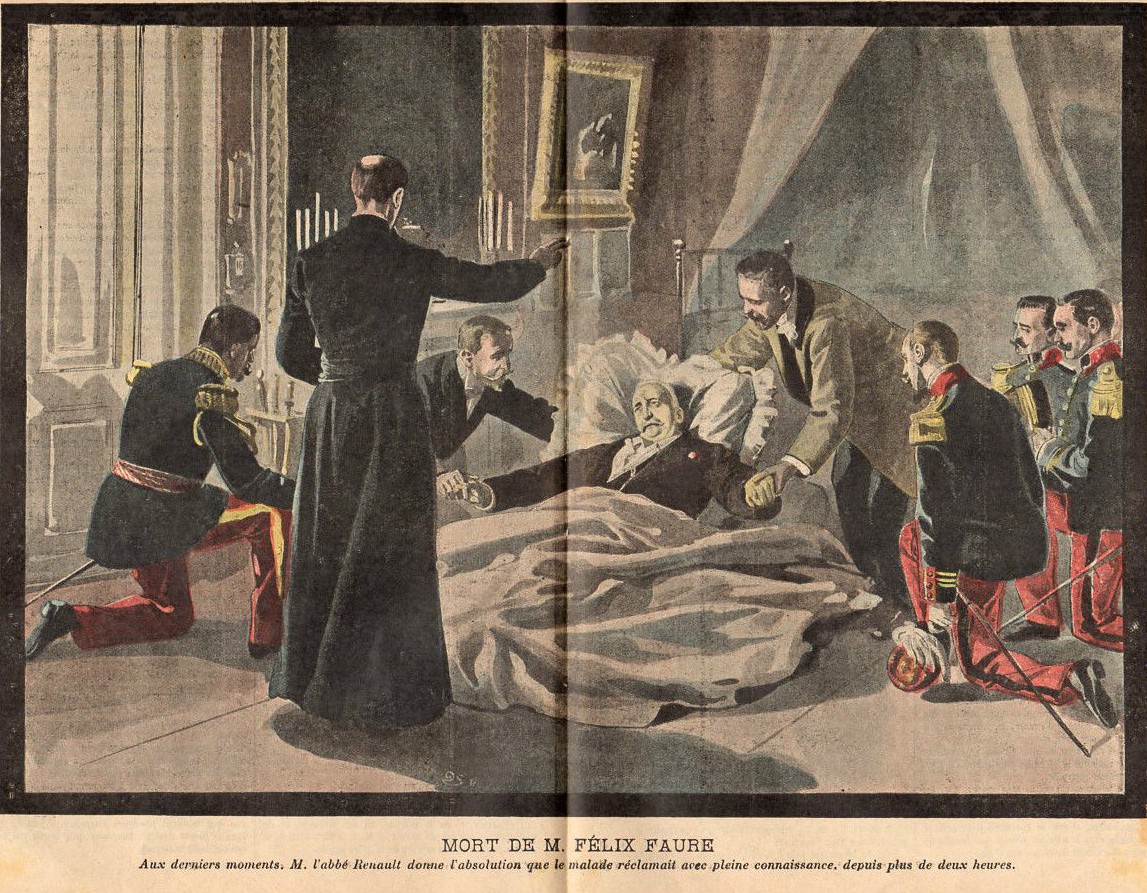

The gorgeous Marguerite married the well-known but less gifted painter Adolphe Steinheil in 1890. The marriage was not a happy one but it allowed Marguerite to move in the highest social circles in Paris. She became the mistress of the French president, Félix Faure, often visiting him for assignations in the Elysée Palace. During one of their trysts Faure died suddenly. The salacious circumstances of the president’s untimely demise (in 1899) and the identity of his companion became widely known thanks to the tabloid press. According to some, presumably his political opponents, it happened while Marguerite was giving the president the Monica Lewinsky treatment, which earned her the nickname ‘La Pompe Funèbre’.

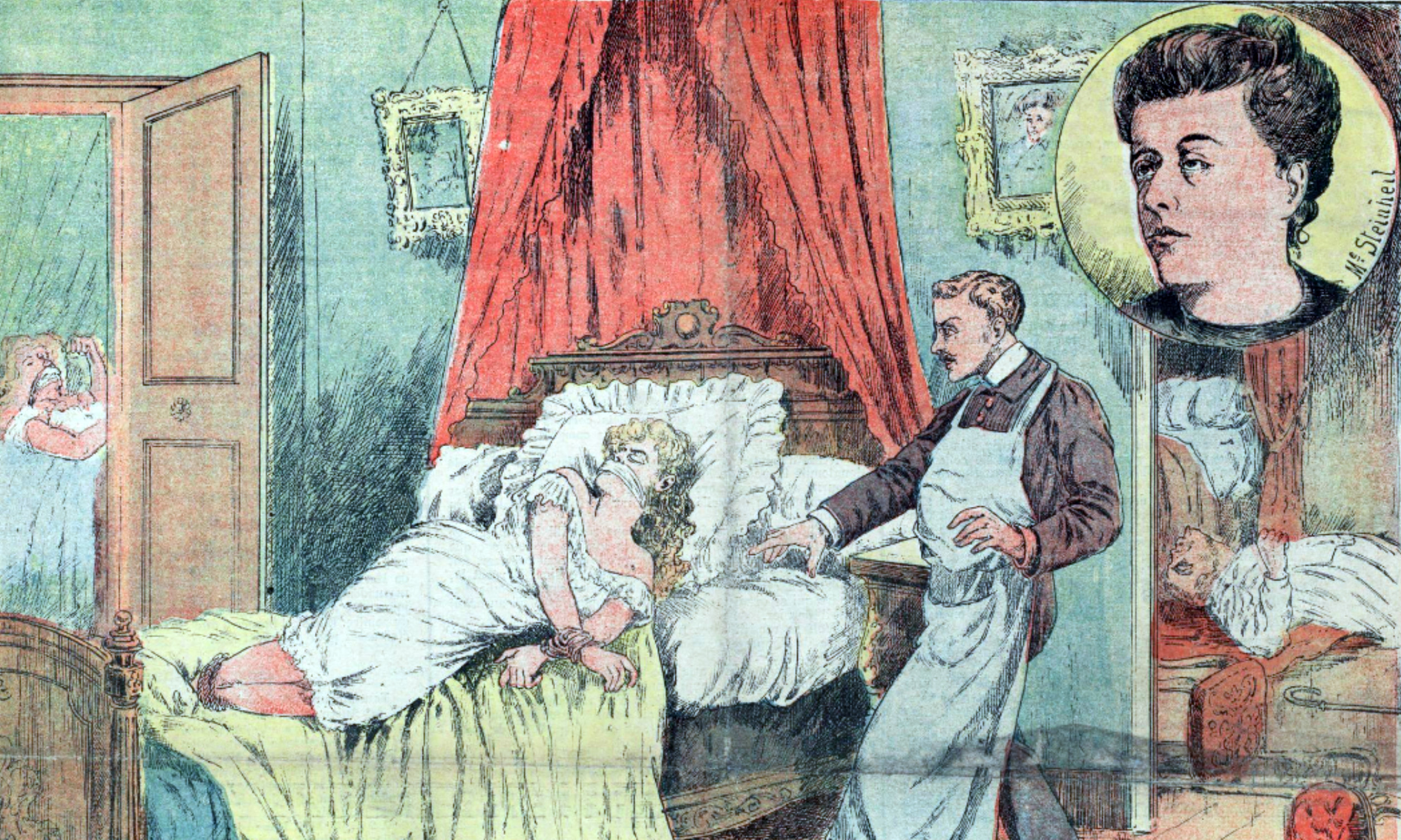

After the president’s death Marguerite continued to have a string of famous lovers. In 1908 Marguerite’s mother and husband were murdered in their bedroom. They both died by strangulation. Marguerite was found bound and gagged but otherwise unharmed. She told the police that a gang of four black-robed burglars had perpetrated the murders and stolen her jewellery.

From the start the police suspected her of playing a part in the murders but couldn’t find proof of this. In an attempt to draw the investigation away from herself, the recent widow tried (unsuccessfully) to frame the male servant who had initially discovered her. She told the police that she had found some of the stolen jewellery in the servant’s possession, including a pearl. Alas for her, a jeweller recognised it as the gem Marguerite had asked the jeweller to dismount from her ring, after the murders took place. So she must have hid it in her servants wallet later on.

Being confronted with her lies, Marguerite at long last accused Alexander Wolff, the son of her old cook Mariette. Alexander Wolff, a horse dealer, called her a vile lying whore. Lucky for him, the police soon proved him entirely innocent.

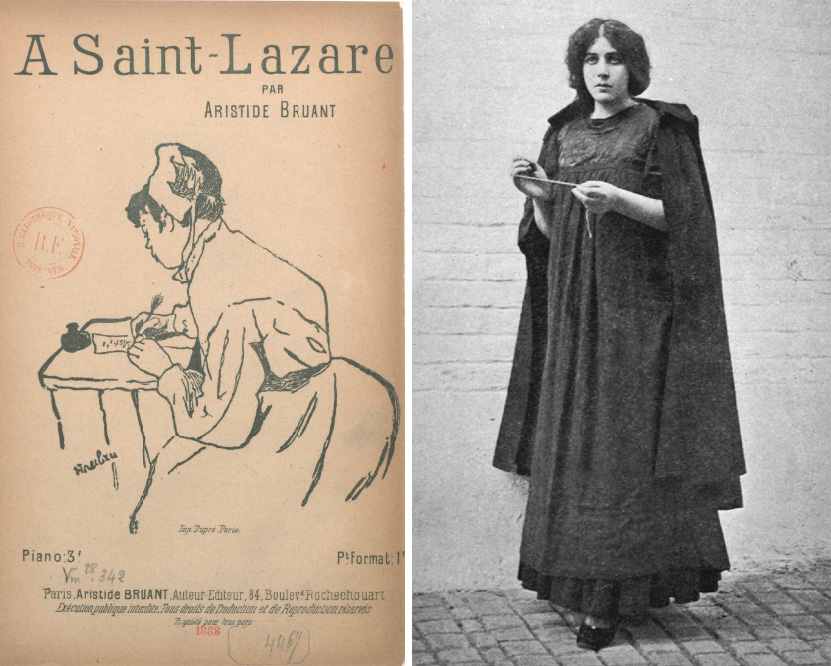

Marguerite’s wild accusations and tampering with evidence, heightened the suspicion against her and finally led to her arrest. She was charged with murder and sent to Saint-Lazare to await her trial.

At that time Saint-Lazare was a gloomy prison for women, housing mostly prostitutes and female thieves. None other than Toulouse-Lautrec (signing as Treclau) illustrated Aristide Bruant’s song ‘A Saint-Lazare’.

In contrast to Bruant’s reputation of singing with a thunderous voice, the wonderful Barbara gave a delicate enactment of the song:

“C’est de la prison que je t’écris mon pauvre Polyte

Et si t’aime bien ta petite souris réponds moi vite…”

The press covered every aspect of the Steinheil murders, the investigation, the arrest, the imprisonment and the trial. Conspirationists pretended that Marguerite had —almost a decade before— also poisoned president Félix Faure.

The trial revealed all her lies and tampering. However, because there was no motive and only indirect evidence of any physical involvement with the murders, she was unexpectedly acquitted and released.

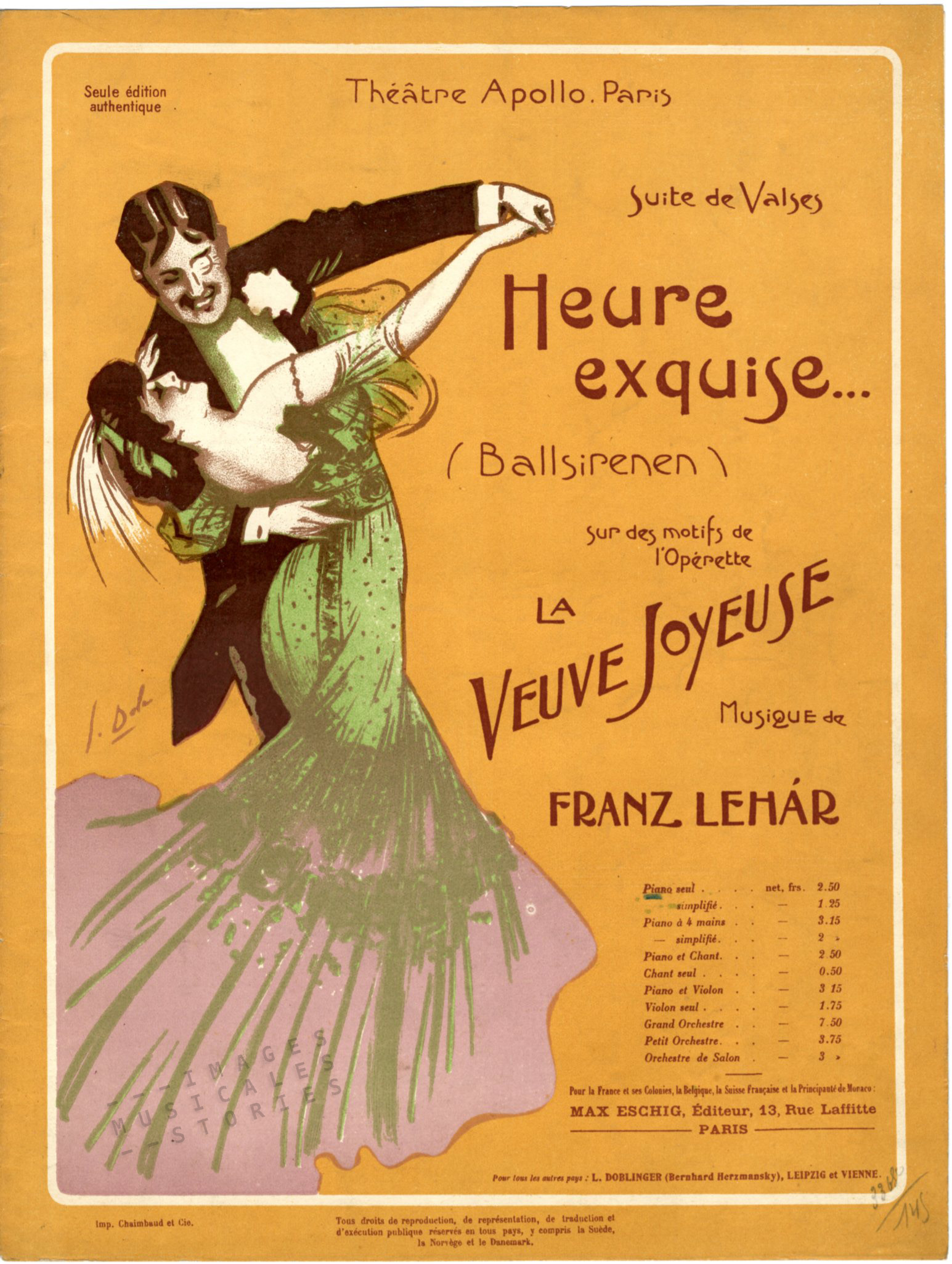

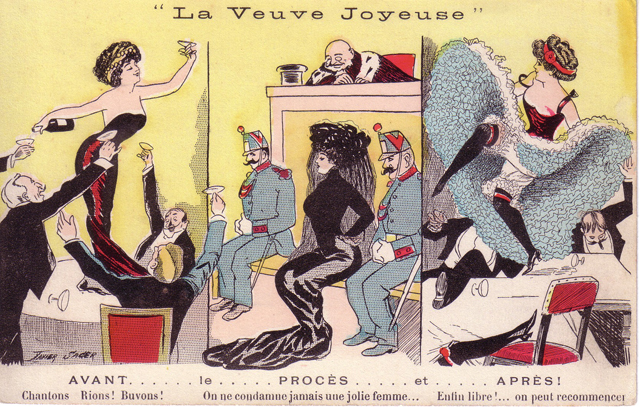

Following her acquittal Marguerite got another nickname: La Veuve Joyeuse after Franz Lehar’s Die Lüstige Witwe (The Merry Widow). The first production of this operetta in Paris had been in April of the same year.

Nonetheless, Marguerite didn’t remain a widow for very long. She changed her name to Madame de Serignac, moved to England where she married into the British aristocracy in 1917 and became Lady d’Abinger.

Marguerite’s faithful cook Mariette stayed in France. She was an important witness at the trial and was described as follows: “Mariette looks an old peasant woman from one of Balzac’s novels. (…) Her nose is strong, and her eyes are terrible—but when she wants to, she can soften their expression. There is hardly any interval between the nose and the stubborn little chin, which reminds one of a dried-up crabapple.”

Notwithstanding that her mistress had accused her son Alexander of the murders, Mariette remained a very loyal servant. At the trial she had said nothing that could possibly harm her boss: “When one is a domestic, one must see everything but say nothing.” This allegiance was not reciprocal. In her 1920 memoir Marguerite wrote: “She had a terrifying appearance, the old Mariette, with her eyes that flashed angrily, her threatening jaw, and her big clenched fists.” Marguerite even hinted that Mariette was implicated in the murders…

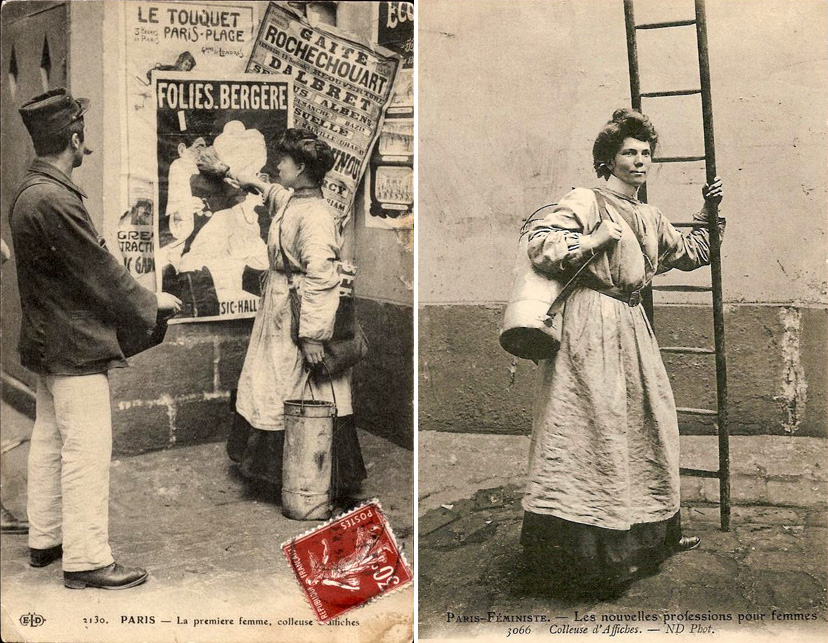

Oddly, after the trial Mariette Wolff became a well-known billposter for the publicity firm Gabert.

Her new boss, monsieur Gabert, had astutely reckoned that her notoriety could well attract the best crowd…

Apart from being an advertiser Gabert was also a keen supporter of feminism and women’s suffrage. He would support the right for women to vote in the elections of 1912. But back in 1908 he already made his point by hiring the first female billposter, until then a profession reserved for men.

Soon onlookers and photographers would assemble around Gabert’s ‘colleuses d’affiches’. These controversial women in a ‘male’ profession first gave rise to surprise and incredulity. But soon they would turn into a spectacle, appearing on postcards as if they were a curio.

Frank, waar haal jij dit interessante nieuws allemaal vandaan.

Maak nu eens een prachtig boek van al jouw schitterende omslagen van bladmuziek. Ik koop dat boek direct !.

DOEN !

Dank je wel Bram, maar dit artikel is wel van Divine.