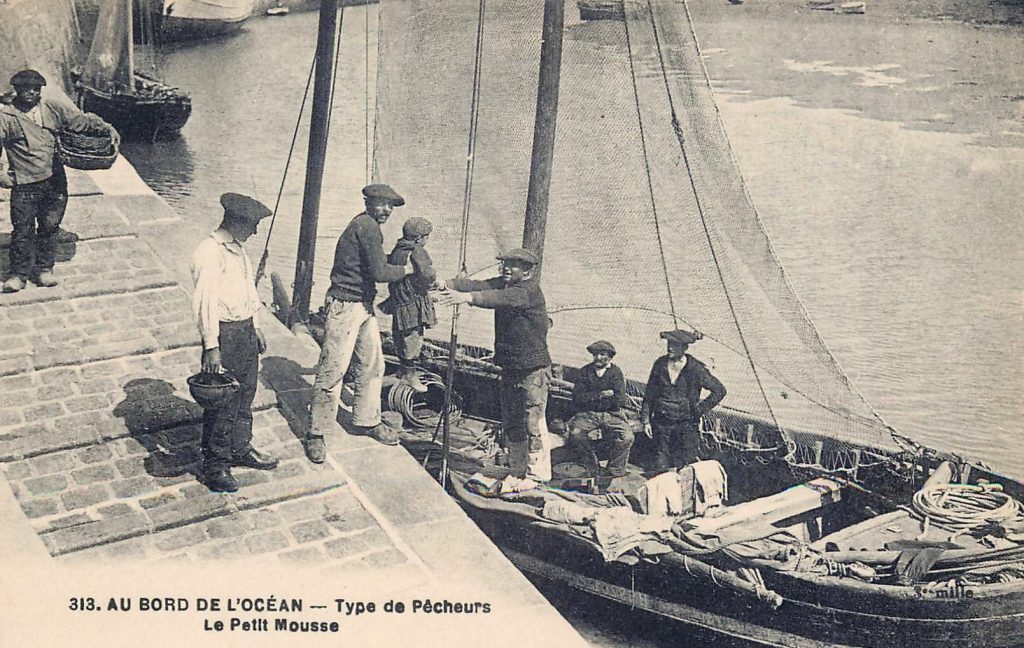

A mousse is the French word given to apprentices carrying out chores on a ship. They used to be young boys, usually 12–16 years old but sometimes as young as 7-8 years old, when they were called a mousaillon. It is only by a decree from 1852 that the boys had to be at least 10 years old to enlist on a ship.

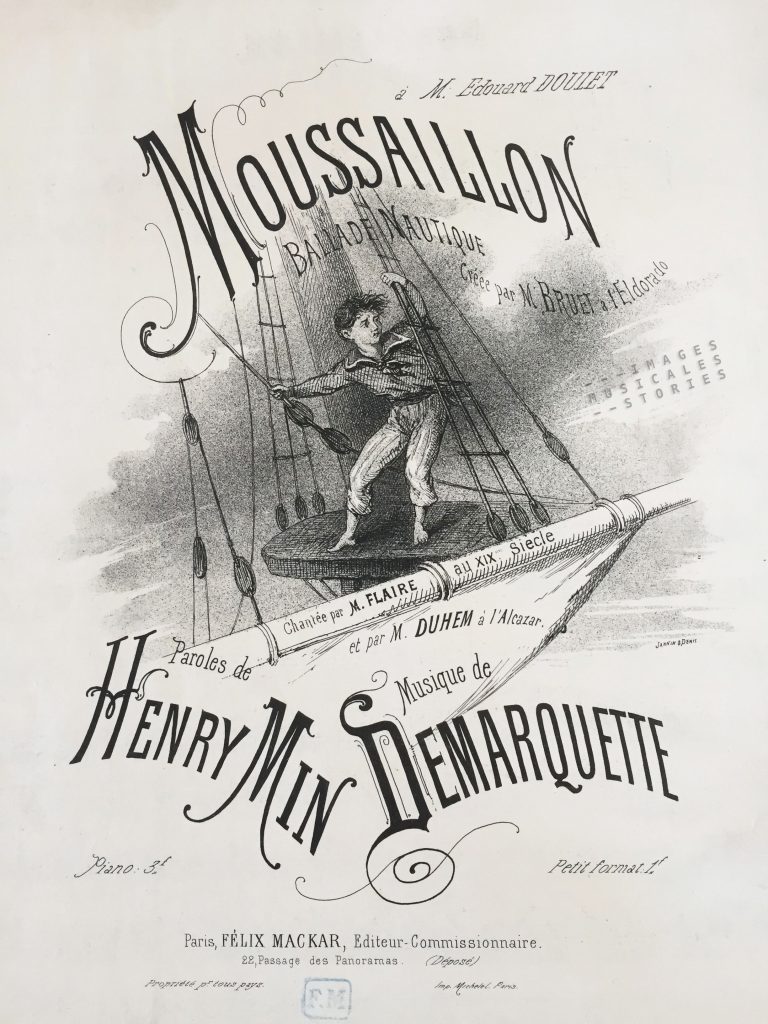

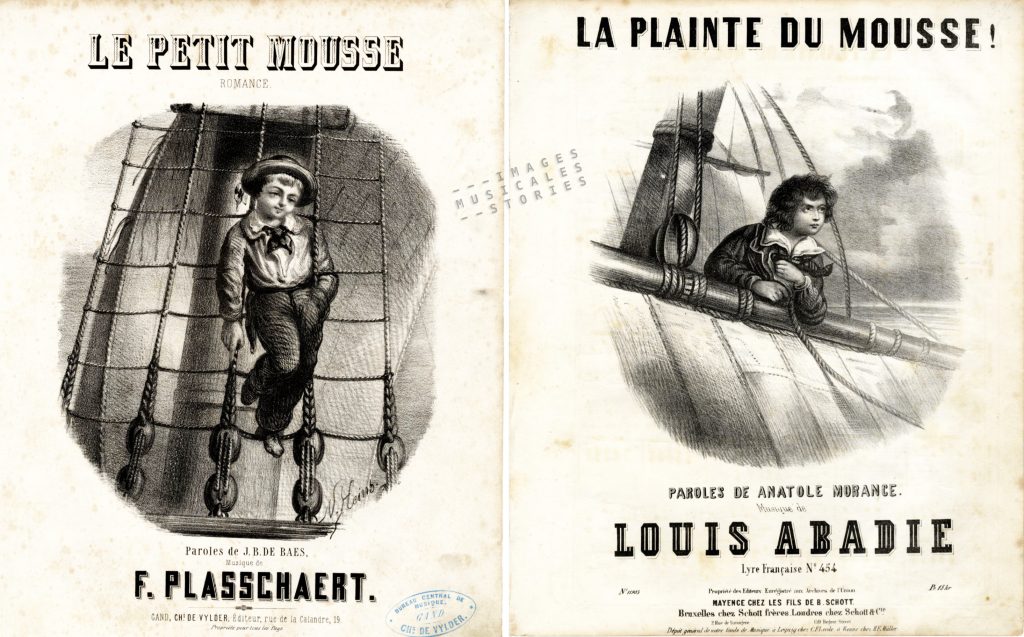

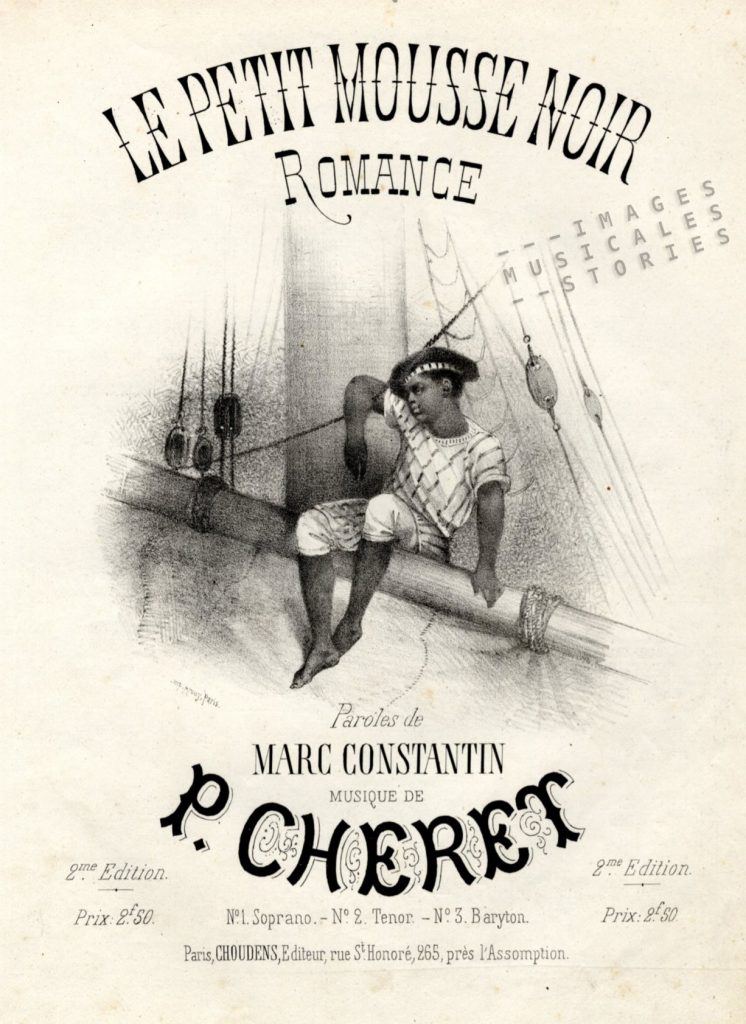

The mousse‘s tasks consisted of cooking meals, sweeping the deck, cleaning the chicken coops, tending the animals, scratching the rust, serving the crew. One other important (and dangerous) duty was to scramble up the rigging, in all kinds of weather, whenever the sails had to be trimmed. It is in this particular role —alone high up in the mast— that the mousse is represented iconographically, time and again.

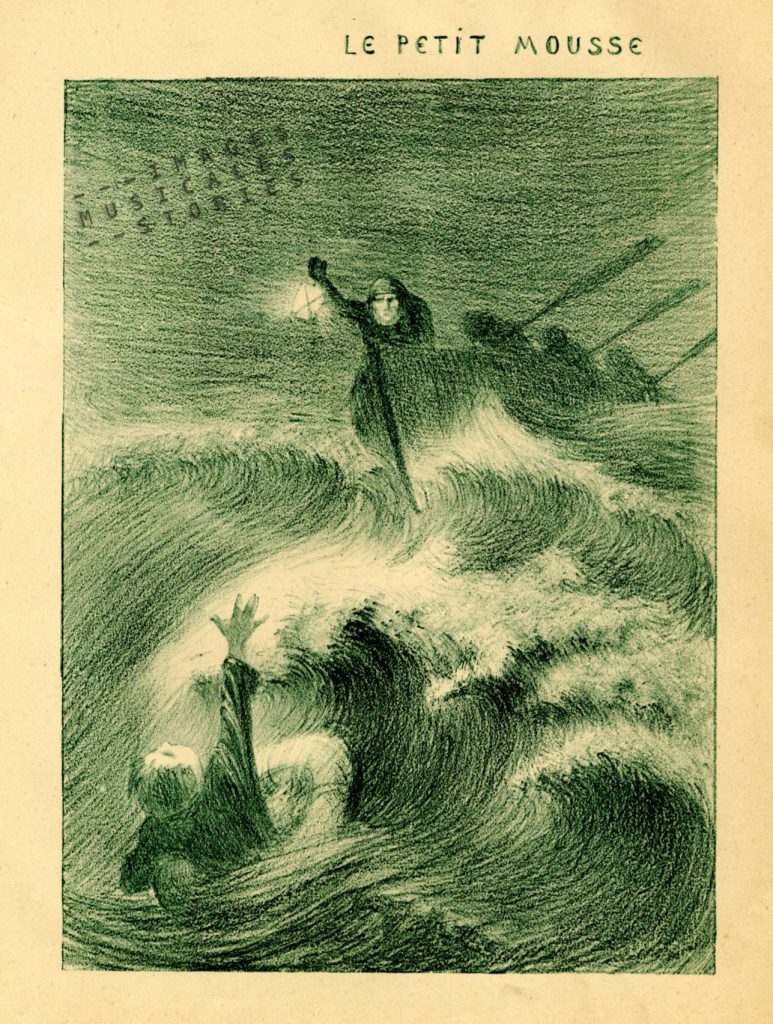

Tales of spectacular shipwrecks and martyred mousses inspired a certain kind of literature, romantic and moralistic novels with a generous portion of melodrama. Also contemporary songs and magazines mawkishly lamented the miserable existence of these children at sea. In these sentimental stories the mousses were either real examples of virtue who earned a living for their family, after their father, a sailor, had perished at sea or had spent everything on booze. Or they were pitiable martyrs who were treated very badly on board: they were caned, flogged or shackled with the rats.

In the Revue des deux Mondes from 1903 an extreme case of maltreatment is described. A mousse was punished for being seasick. He had to stand on deck, with a heavy wooden bar on his shoulders, and was left there for days on end. The child, at the slightest roll, stumbled, slipped on the deck, got soaked to the skin and shivered from the cold. Then, as he did not toughen up quickly enough, his hat and muffler were cut off. The sleeves of his jacket and shirt were lifted up to his elbows, and his trousers up to his thighs. By temperatures below zero his skin turned bluish. He was kicked and clubbed there where wounds began to form. He was deprived of food, and, not surprisingly the poor mite died. In the same magazine, another mousse accused his captain of sexual abuse but as it could not be proven the captain went free.

The normal life for most of the mousses was not as horrendous. Although it was absolutely not an easy living. No laws regulated their working conditions. Captains, usually with a drinking habit, were quite often uneducated and brutal. Luckily for some of the mousses, especially those on local fishing boats and small coasters, the crew knew each other and

The normal life for most of the mousses was not as horrendous. Although it was absolutely not an easy living. No laws regulated their working conditions. Captains, usually with a drinking habit, were quite often uneducated and brutal. Luckily for some of the mousses, especially those on local fishing boats and small coasters, the crew knew each other and in many cases the captain, or someone in the crew, was related to the mousse.

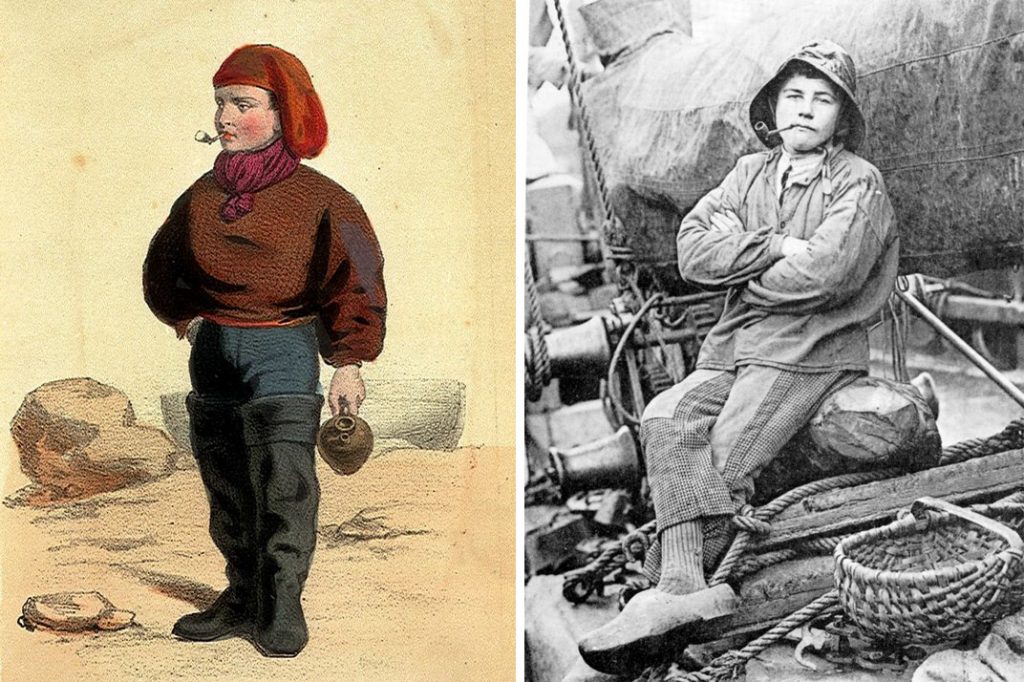

Nevertheless this kind of apprenticeship was much too harsh and rough for such young boys. They had to act as adults much too early. There were frequent cases of sexual abuse and allegedly a lot of the mousses had syphilis. They smoked and drank alcohol: typically a mixture of coffee, cider, eau de vie and lots of sugar. Apart from a few initiatives in the first half of the 19th century to provide a minimal education, it was not until the 1950s that mousses got a proper schooling.

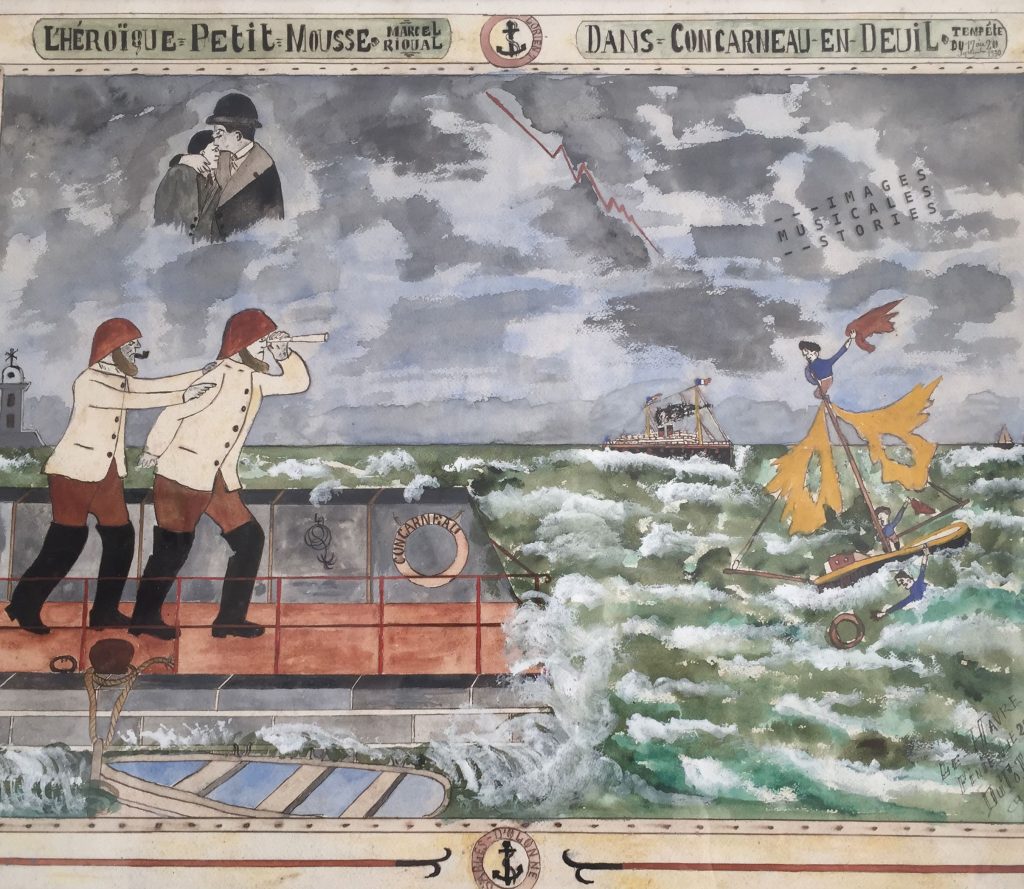

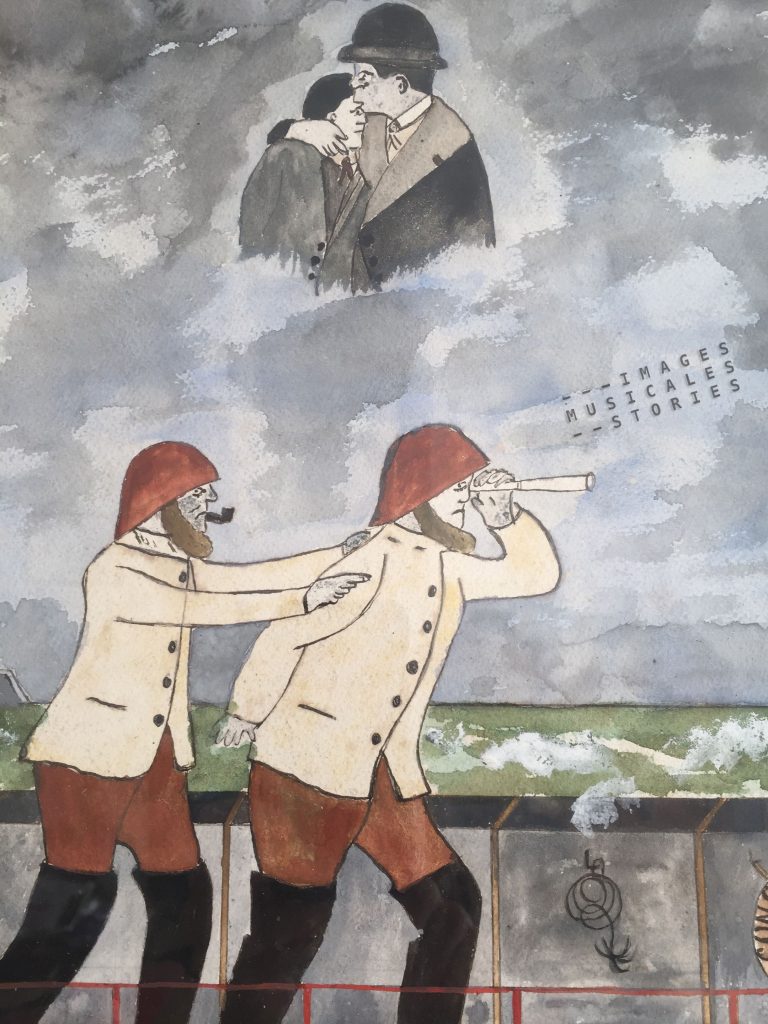

Now comes the story of the heroic petit mousse Marcel Rioual. While writing this story, I’m looking at a painting depicting Marcel’s real-life tragedy at sea.

The sixteen-year old Marcel had registered on board of a dundee called the ‘Bon-Retour’. A dundee was a fast tuna boat with an over-extended stern typical for Brittany. In September 1930 a fierce storm hit Brittany, brutally exposing the weakness of the dundee. Like so many other boats, the ‘Bon-Retour’ was in distress and two sailors were swept away. The water filled the boat but the pumps were broken. The rest of the crew desperately tried to empty the hold with buckets. When Marcel saw that the ship’s wheel was abandoned, he attached himself to it and clang to it during twenty-four hours, thus hoping to survive the raging sea.

The sixteen-year old Marcel had registered on board of a dundee called the ‘Bon-Retour’. A dundee was a fast tuna boat with an over-extended stern typical for Brittany. In September 1930 a fierce storm hit Brittany, brutally exposing the weakness of the dundee. Like so many other boats, the ‘Bon-Retour’ was in distress and two sailors were swept away. The water filled the boat but the pumps were broken. The rest of the crew desperately tried to empty the hold with buckets. When Marcel saw that the ship’s wheel was abandoned, he attached himself to it and clang to it during twenty-four hours, thus hoping to survive the raging sea.

At some point the Bon-Retour —I don’t know how— finally touched the port of Concarneau. It was devastated by the storm and its deck was strewn with ropes, pieces of sail and wood. Only its mast was still standing, the flag at half-staff. After being treated by a doctor, Marcel modestly said “I just did what I had to do”.

At some point the Bon-Retour —I don’t know how— finally touched the port of Concarneau. It was devastated by the storm and its deck was strewn with ropes, pieces of sail and wood. Only its mast was still standing, the flag at half-staff. After being treated by a doctor, Marcel modestly said “I just did what I had to do”.

Marcel was also greeted by the Minister of Merchant Marine. That encounter was related in the press, together with a photograph of the embrace.

Clearly that picture inspired our amateur painter to represent the fatherly embrace in the clouds of the deadly storm. This naive work by an amateur painter may seem clumsy and funny. However it is testimony to the pain and mourning of the whole Finistère region, as 207 sailors died in that storm of 1930.

This naive work by an amateur painter may seem clumsy and funny. However it is testimony to the pain and mourning of the whole Finistère region, as 207 sailors died in that storm of 1930.

Stories of spectacular shipwrecks and heroic mousses have inspired young adult novels in pulp magazines, even as late as the fifties.

In Ambleteuse, the small French coastal village facing the English Channel where I am writing this story, there is this fast-food ‘restaurant’. Au Petit Mousse offers typical French cuisine: pizza, Welsh and kebab.

Although their logo on the menu might be politically offensive, they were perhaps inspired by an old sheet music cover…

I enjoy your contributions very much.

While you mention Le Petit Mousse in Ambleteuse, I will add to this – staying in the sphere of the Summer Blues – Camping Le Petit Mousse ( http://www.campinglepetitmousse.com ) au Mediterranee.

I also found Le Petit Mousse on Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-LBGohMiQ1U .