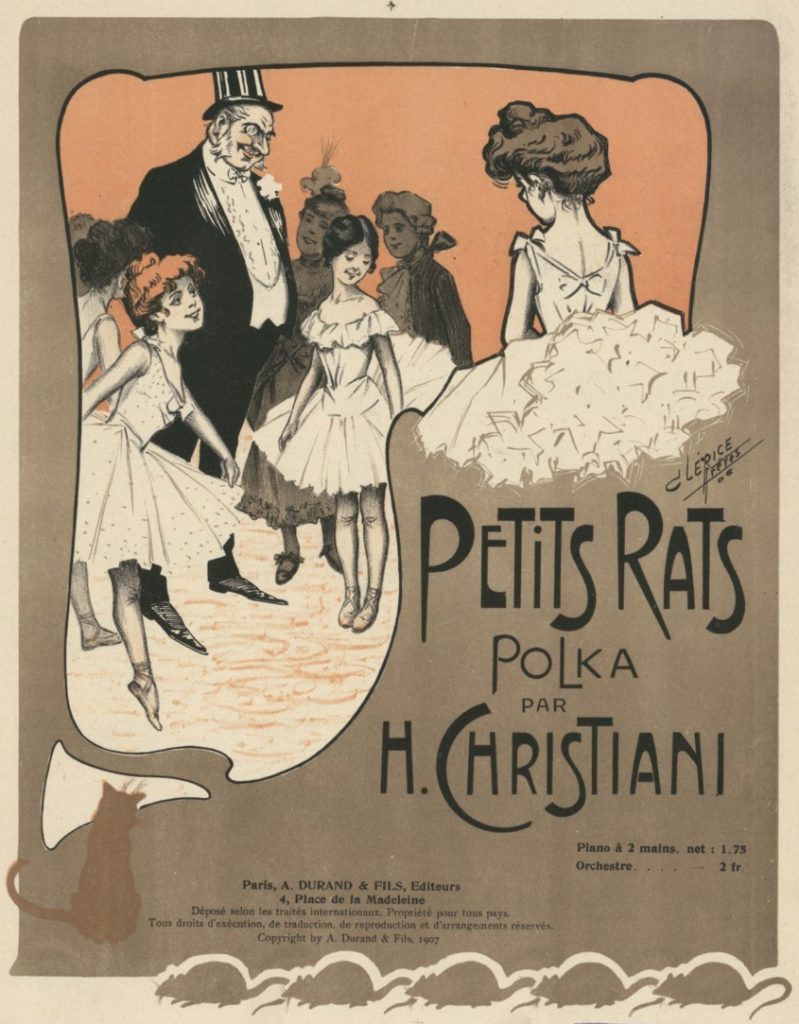

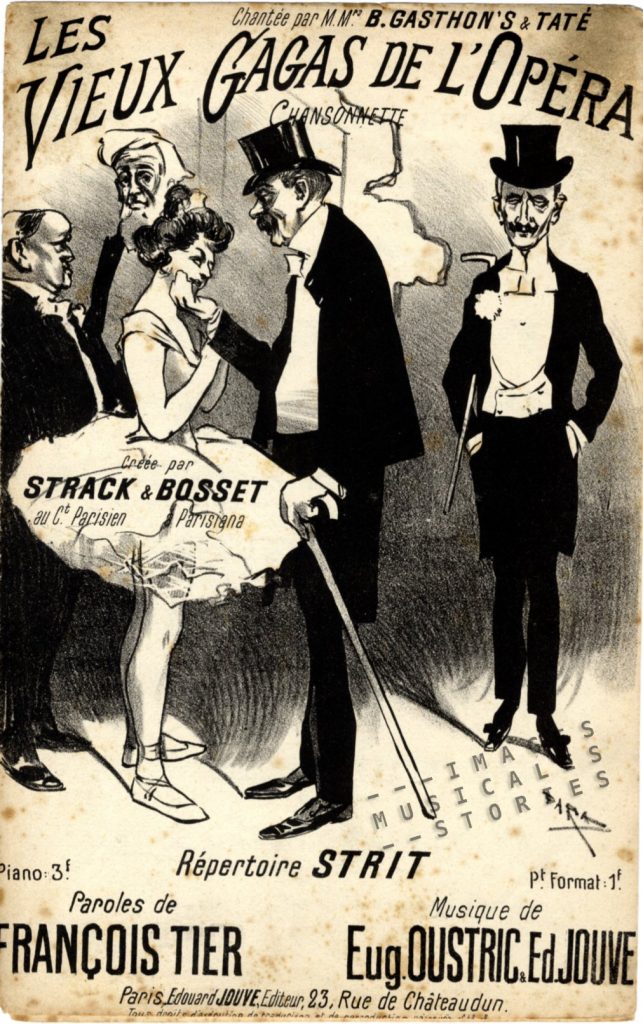

The gesture of a wealthy man patronisingly lifting the chin of a ballerina hides a grim and sordid truth.

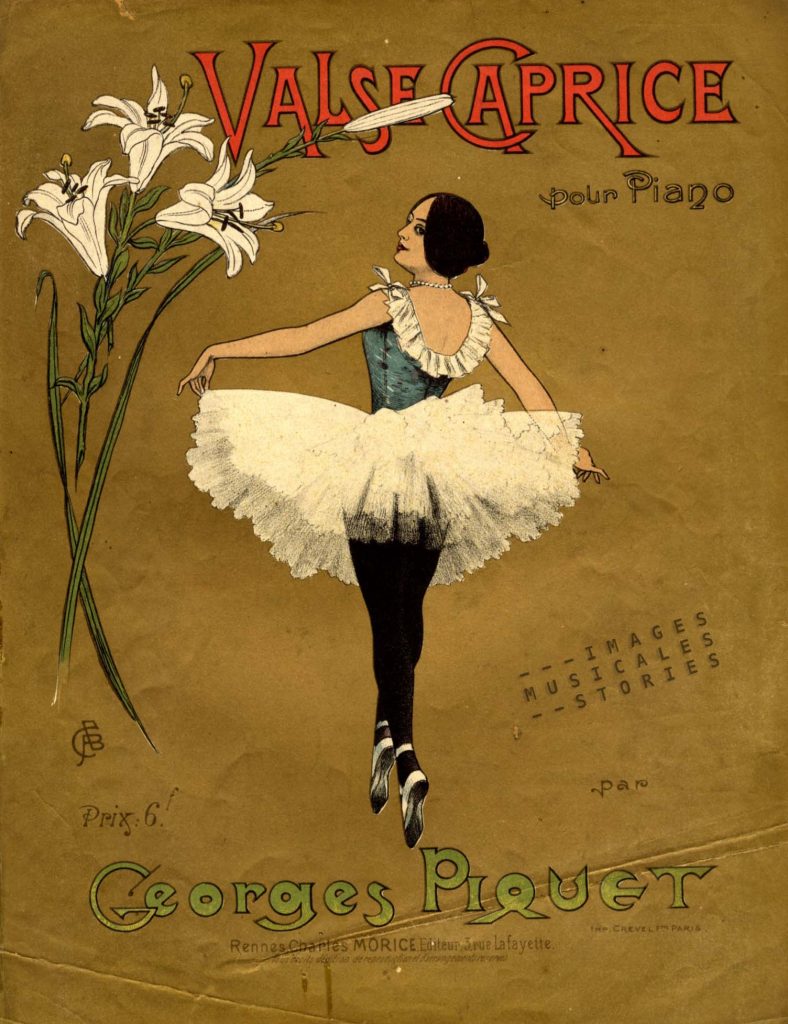

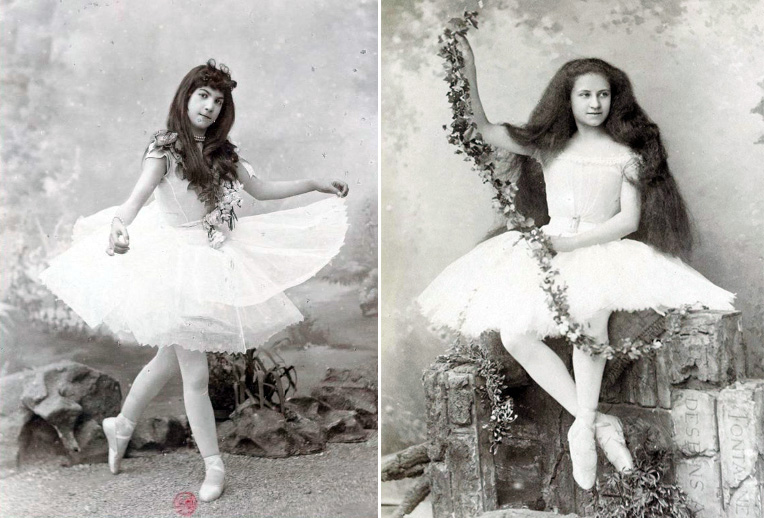

In the 19th century most ballet dancers of the Parisian Opera came from poor and deprived families. They were also often illiterate. Sometimes a family’s hope for a better future rested on the frail shoulders of a daughter with dancing skills. These young ballerina’s were commonly called Les Petits Rats, or the little rats of the opera.

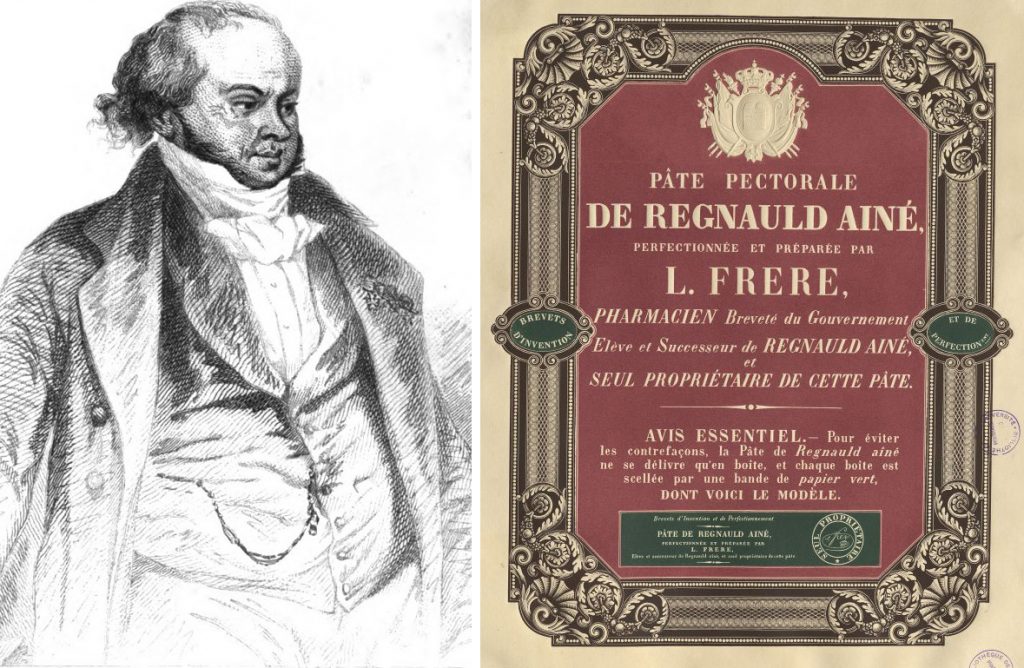

Around 1830 Louis Véron, a short corpulent man, became the new administrator of the Parisian opera. Véron was a trained physician turned businessman who had made fortune from cough drops (Pâte pectorale de Reginauld Ainé). He had arranged a lucrative deal that yielded two-thirds of the profits to him without having to work.

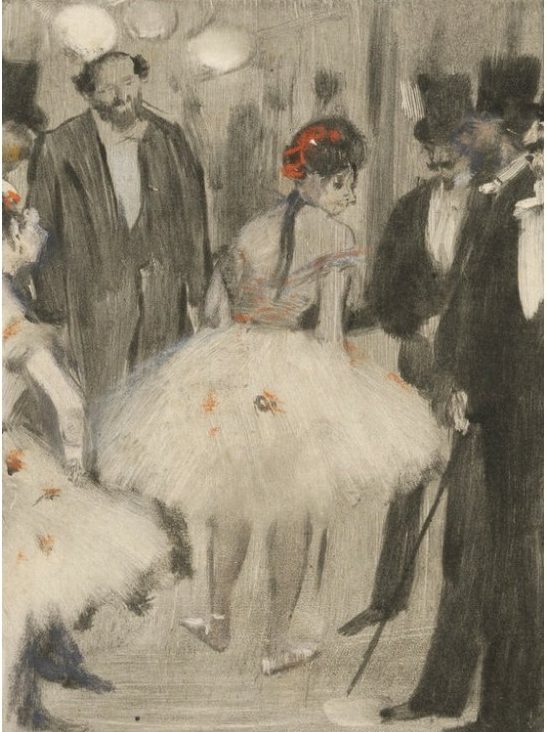

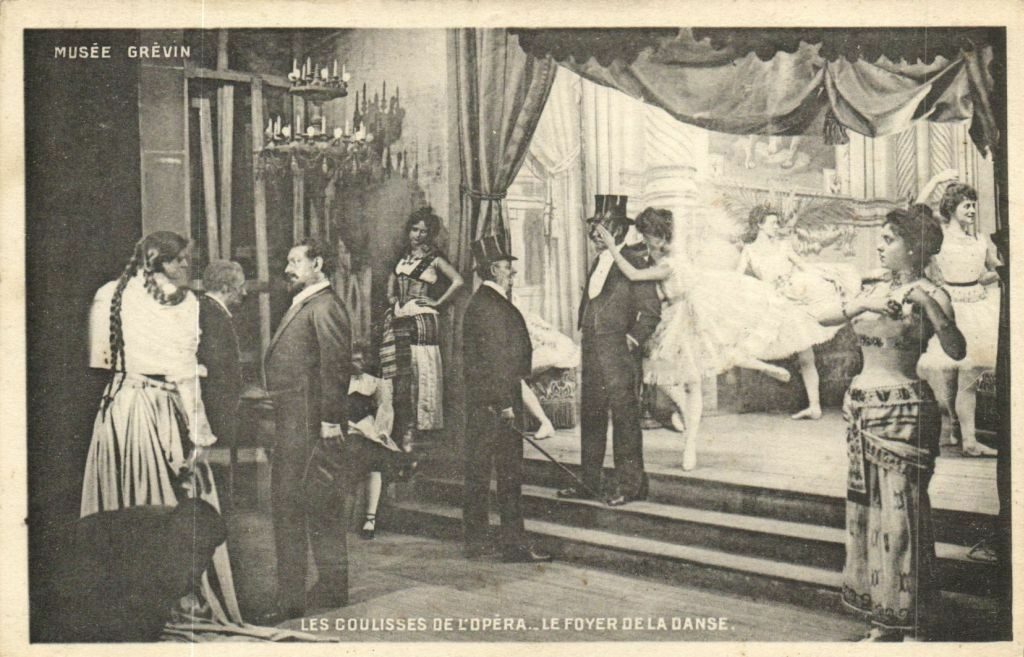

Véron devised several strategies to make the opera profitable. One was to create the Foyer de la danse, an exclusive and lavishly decorated backstage salon. Véron, the shrewd entrepreneur, offered to the well-heeled season ticket holders or abonnés not only a private theatre box, but also secluded access to this backstage. There the wealthy male abonnés enjoyed a kind of droit de seigneur over the little dancers.

Astonishingly to modern standards, these men in top hats had obtained the right to prowl the corridors and meet the (very young) ballet dancers in the lavishly decorated Foyer de la danse. They could enjoy informal performances and hold private parties with the danseuses. In the corridor leading up to the Foyer, they could negotiate with the ‘mothers’ the right fee to get an ‘introduction’ to a pretty dancer.

The most affluent of these abonnés were the members of the Jockey Club. This club was the epitome of exclusivity, its elite members solely being aristocrats. They were connoisseurs of horses, cigars and women. Their preferred part of the opera was the ballet. At that time the ballet was often nothing more than a choreographic interlude performed during the second part of an opera. The members of the Jockey Club used to dine during the first act. They then arrived at the opera just in time to admire their protégées on the gaslit stage, and —immediately after the ballet— left quickly for the Foyer… (*)

Another strategy of Véron was to decrease the wages of the dancers, thus forcing the girls to find a wealthy protector. In this way Véron set up a patronage system for the opera’s corps de ballet based more or less on sexual services. The opera had become a place where there was art on the one hand and prostitution on the other.

But the story becomes even more Dickensian or Zolaesque. The opera also housed the ballet school. Girls as young as ten had to work up to twelve hours a day, six days a week, dividing their time between lessons, rehearsals and shows. Arriving too late or faults were fined. They had to live close to the Opera, because with their meagre pay they couldn’t afford the tram or omnibus. Only a minority of these young dancers would become famous and earn a salary sufficient to support their family. Meanwhile, some mothers hunted for a rich protector for their (underage) daughters.

At first Marie was a respectable dancer of the corps de ballet. But a year after the Degas statue was exhibited (1881) she went off the rails. Marie’s older sister Antoinette, had robbed a man in Le Chat Noir. She was arrested and put in prison for three months. The evidence at the trial made it clear that her mother was prostituting her. It is supposed that Marie was also on the game because she started to miss her appointments in the Opera until at last she was sacked.

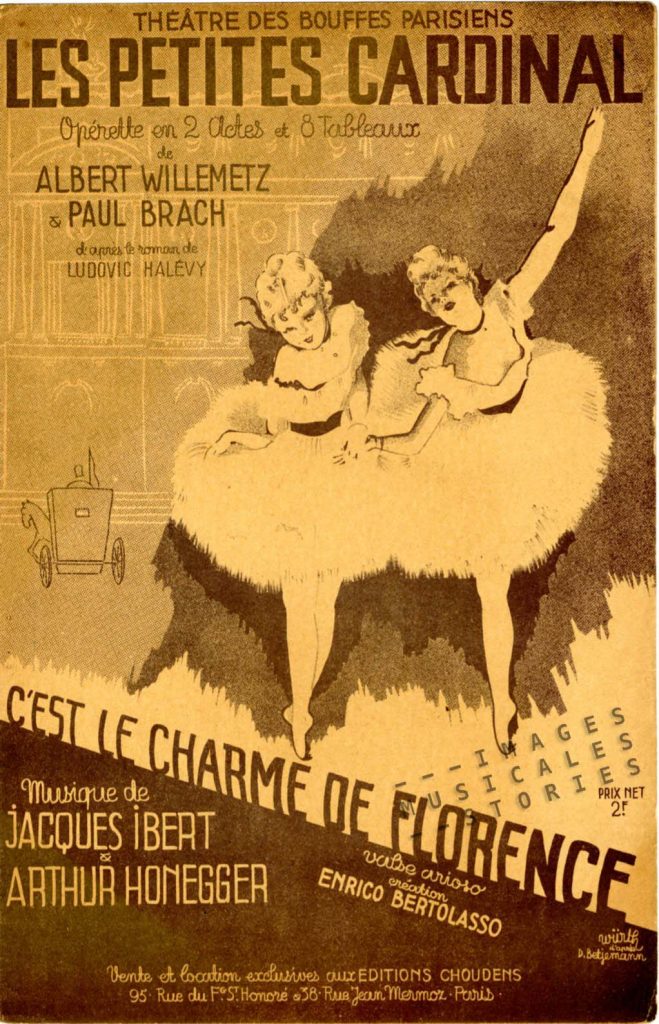

Degas also illustrated the short stories Les Petits Cardinal written by his friend Ludovic Halévy. These stories tell, slightly veiled, about the obvious similarities between life at the Opera and scenes in a brothel where the abonné is the client, the dancer is the prostitute, and the mother is the madam.

The Musée Grevin, the Parisian wax museum, understood that the Foyer de la danse captured the public imagination and made it into a tableau. It was exhibited from 1890 on, for eleven years. It offered the visitor a voyeuristic peek behind the scenes on how the rich abonnés got entertained. The representation of the Foyer de la danse was Grévin’s greatest success after the famous crime scenes.

It was only from 1927 on that the director of the opera, Jacques Rouché, tackled the problem of the excesses at the Foyer de la danse

It was only from 1927 on that the director of the opera, Jacques Rouché, tackled the problem of the excesses at the Foyer de la danse. His newly nominated Ballet Master, Serge Lifar, supported him fully. Under the dramatic protests of the abonnés they banned the backstage access to the Foyer de la danse, and made from the ballet in the opera a real art form. The film The Ballet of the Paris Opera, featuring Serge Lifar, dates from that period.

(*) When Wagner broke with the tradition and included a ballet in the first act of Tannhauser instead of in the second act, the members of the Jockey Club arrived too late to ogle their young protégées. They booed during the 1861 Parisian premiere and for the next two performances of Tannhauser, they disturbed the performances to such an extent, distributing whistles and rattles to the audience, that Wagner was forced to withdraw the opera after three performances.

I would like to congratulate you for your wonderful usage that you are doing with your sheet music covers!

I’m also a sheet music collector from Paris (French songs and American tunes)

I live in Montmartre near Pigalle

All the best

Philipp

Fascinating (if disturbing) post. You probably already know of this tangential movie thread, but in case: Jacques Feyder’s Les nouveaux messieurs (made from a 1925 play) covers the same theme.

https://www.cinematheque.fr/catalogues/restaurations-tirages/film.php?id=48577

More playful than critical (not exposing the tender ages of the ballerinas that I recall) but parliament still felt exposed and it was held from release, then later released with what film historian Lenny Borger calls “unkind cuts. “