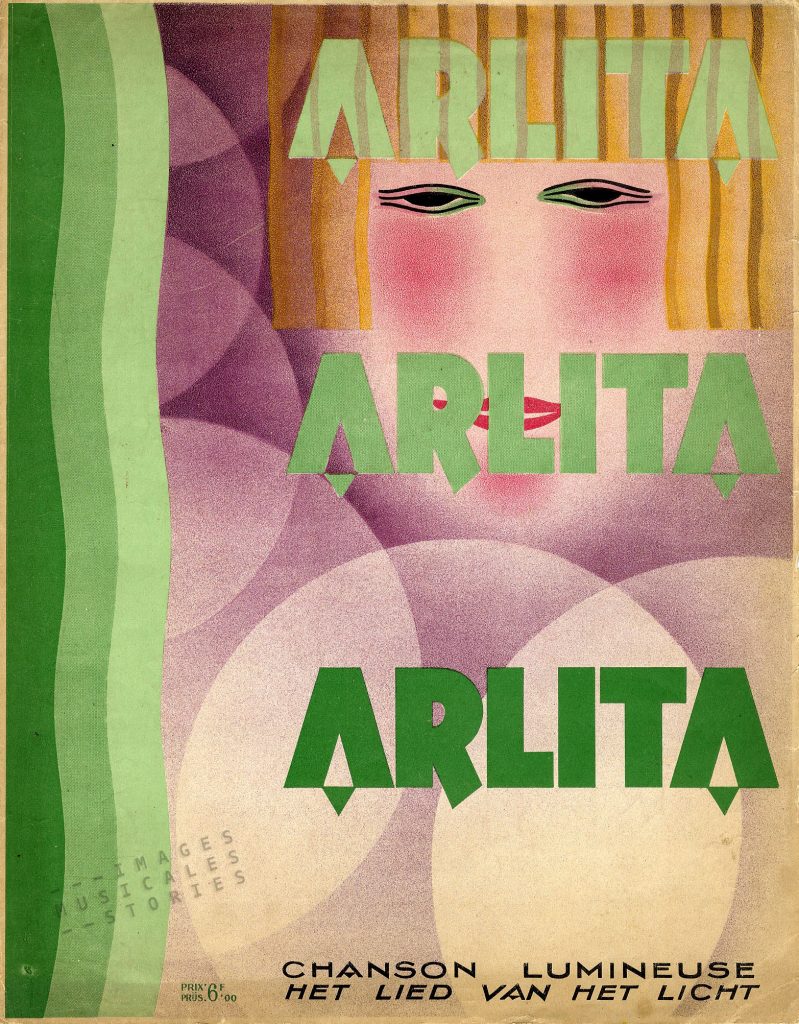

This superb geometrical cover suggests the song is about a beautiful girl named Arlita. Far from it though, it prosaically sings the technological praise of a light bulb! The glass lamp is represented here by large discs in shades of purple around the fleshy rose face of a girl. The design is attributed to Marcel-Louis Baugniet (1896-1995) a Belgian painter, furniture designer and decorator. The drawing certainly reflects his style which was influenced by Bauhaus, cubism, De Stijl and Russian constructivism.

In the girl’s traits many like to recognise the portrait of the Brussels dancer and artist Akarova (born Marguerite Acarin, 1904-1999).

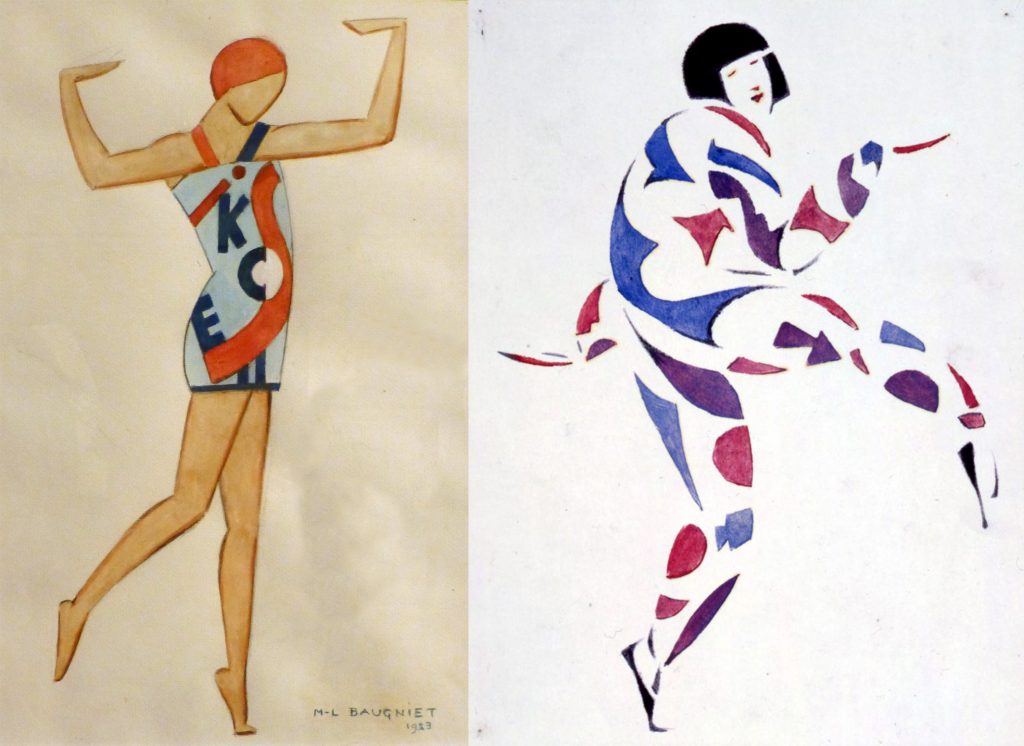

Akarova was an emancipated garçonne. Her fame as a dancer earned her the unofficial title ‘the Belgian Isadora Duncan’. In 1922 she married Marcel-Louis Baugniet. Both designed the avant-garde costumes and decors for her stage performances and continued to do so after their rather brief marriage. They stayed friends though, and both lived well into their nineties.

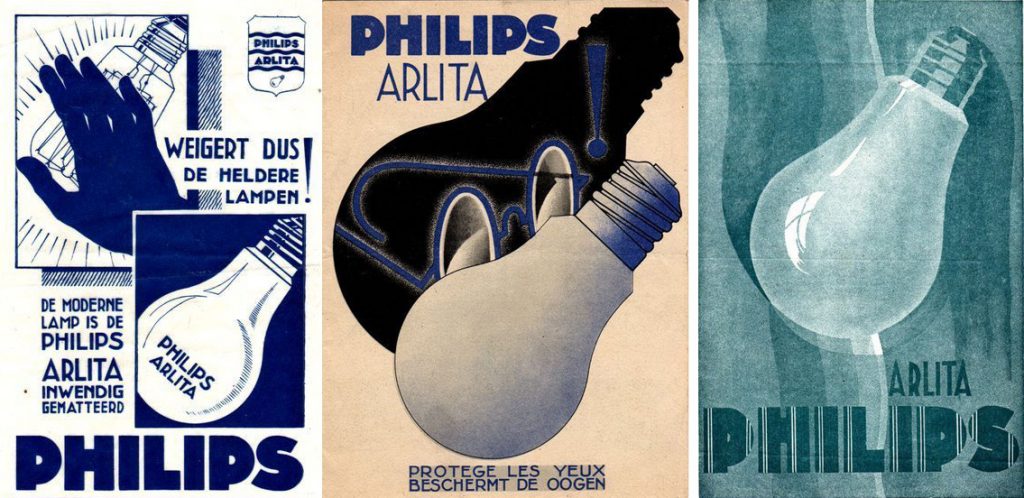

Philips, the producer of the Arlita light bulb, is a Dutch company founded at the end of the 19th century. Immediately after WWI a Belgian branch was established. From there the Arlita lamp was manufactured and launched in 1929. A massive advertising campaign —including press articles, brochures, publicity folders, albums and posters— heralded the birth of the frosted lamp.

It is in this marketing storm that one has to situate the sheet music above. The song and the publicity celebrated Arlita as a wonder of technology and cost cutting. To deliver this last message the marketeers even introduced a nasty Gollum-like figure: the current devourer (or stroomvreter in Dutch).

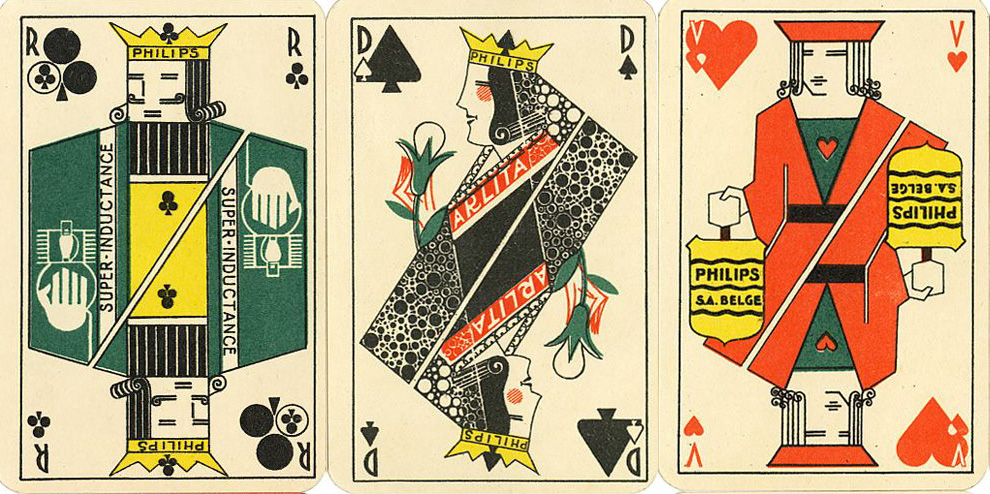

The marketing strategy led to a commercial success. The Arlita sales soon accounted for 80% of the turnover. The Arlita bulb was followed by the super Arlita, and then came the bi-Arlita with a double filament. One man was at the heart of the marketing operations: Jacques Vink. He had been involved with the international advertising department of the Philips house in the Netherlands, before becoming head of the Belgian branch. From his beginnings in 1907 Vink regularly gave artists assignments to create publicity. And once in Belgium it was but a further step to ask avant-garde Belgian artists to design merchandising in order to promote the Philips light bulbs. In this way he ordered this silverware salt shaker from Oskar Wiskemann…

… and a set of playing cards with various instances of the lamp, hidden in the pictures.

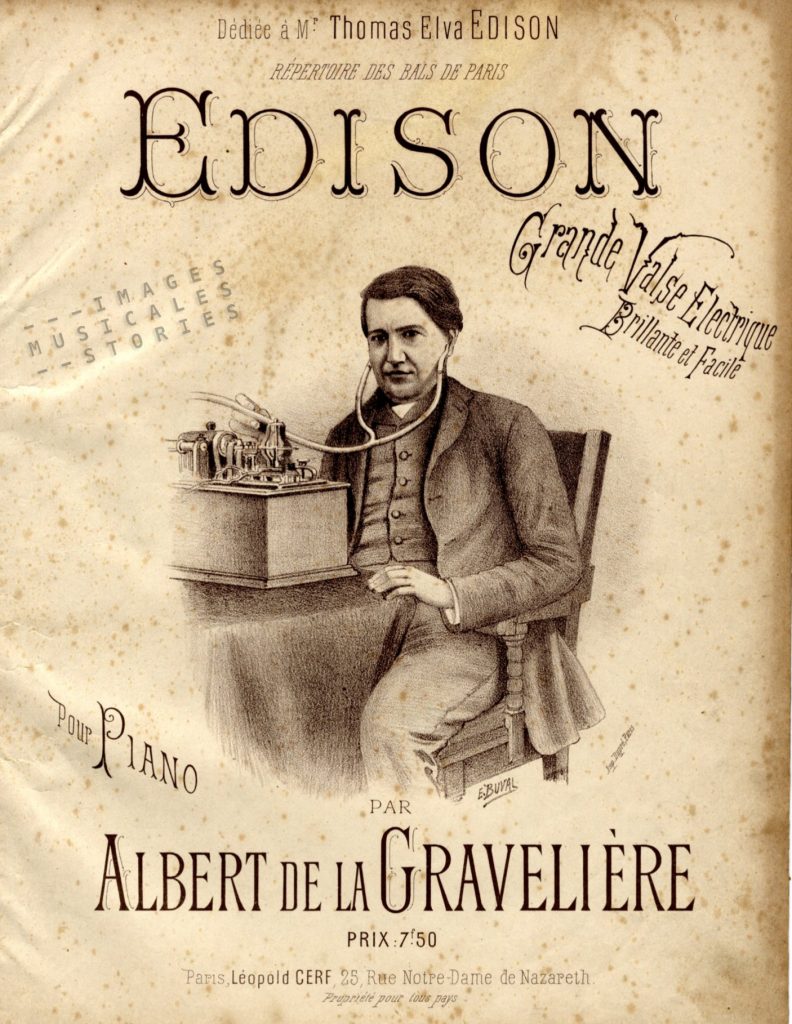

The Arlita campaign coincided with the fiftieth anniversary of the invention of the light bulb by Thomas Alva Edison. To anticipate this event Philips supported a series of school lectures throughout Belgium. Moreover, Jacques Vink also devised a delicate attention for the parents who’s baby was born on October 29, 1929. They received a luxury box with an Arlita lamp. He even sent one to Edison himself who replied with a friendly letter.

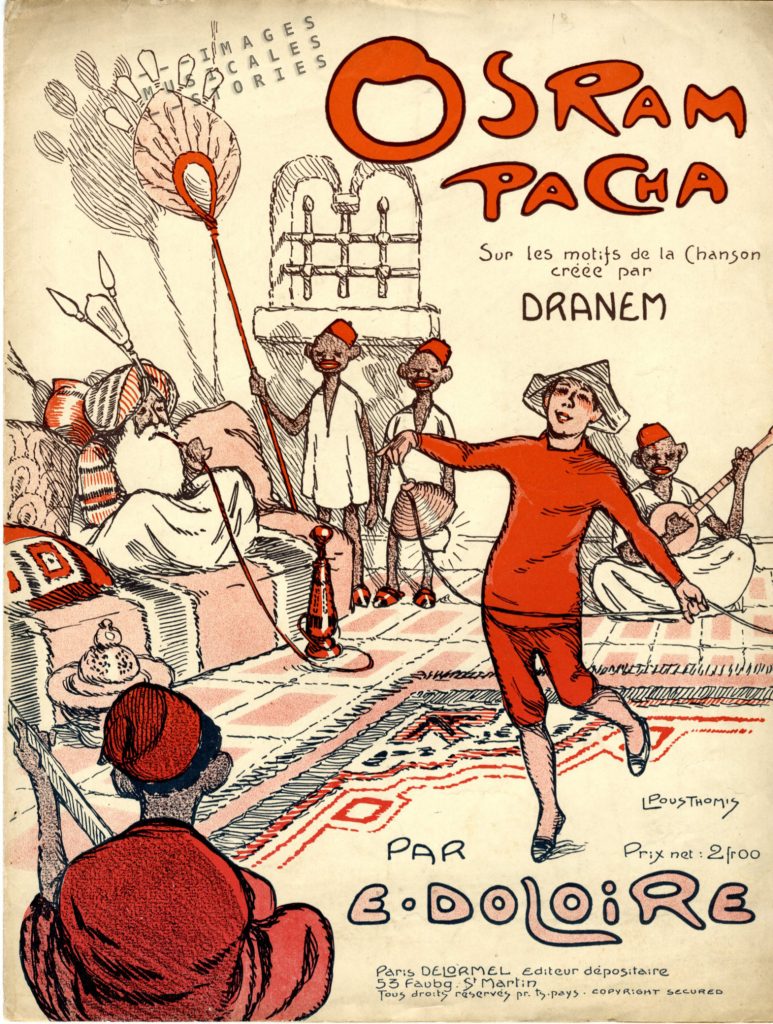

We discovered in our collection another publicity for light bulbs. It is more than a decade older and is for Osram, the German competitor of Philips. The name of the light bulb holds an oriental flavour: Osram Pacha.

The illustration is by Pousthomis who got his inspiration from a 1911 poster by D. Vasquez Dial. The composer fantasised about the brand name Osram, which is derived from osmium and wolfram (German for tungsten). Both these elements were commonly used for lighting filaments. Maybe the name Osram, in its resemblance to Osman I, the founder of the Ottoman empire, inspired Pousthomis to draw this oriental dance setting for the German light bulb. This consonance can also explain why the lamp was christened Pacha, ‘pasha’ being an honorary title in the Ottoman empire.

We will end with a documentary as a tribute to Thomas Edison, who is granted the invention of the incandescent bulb although it is the work of many inventors, rather than his lone genius. A pity he didn’t invent a hearing aid.

THE ELECTRIC LIGHT GALOP

This wonderful illustration by Alfred Concanen is an idealised version of Siemen’s arc-lamp trial in the City Of London circa 1881. Each arc lamp was fitted with a clear glass globe and the masts were constructed from light iron trellis work. Here, they are mounted in front of the Bank of England.