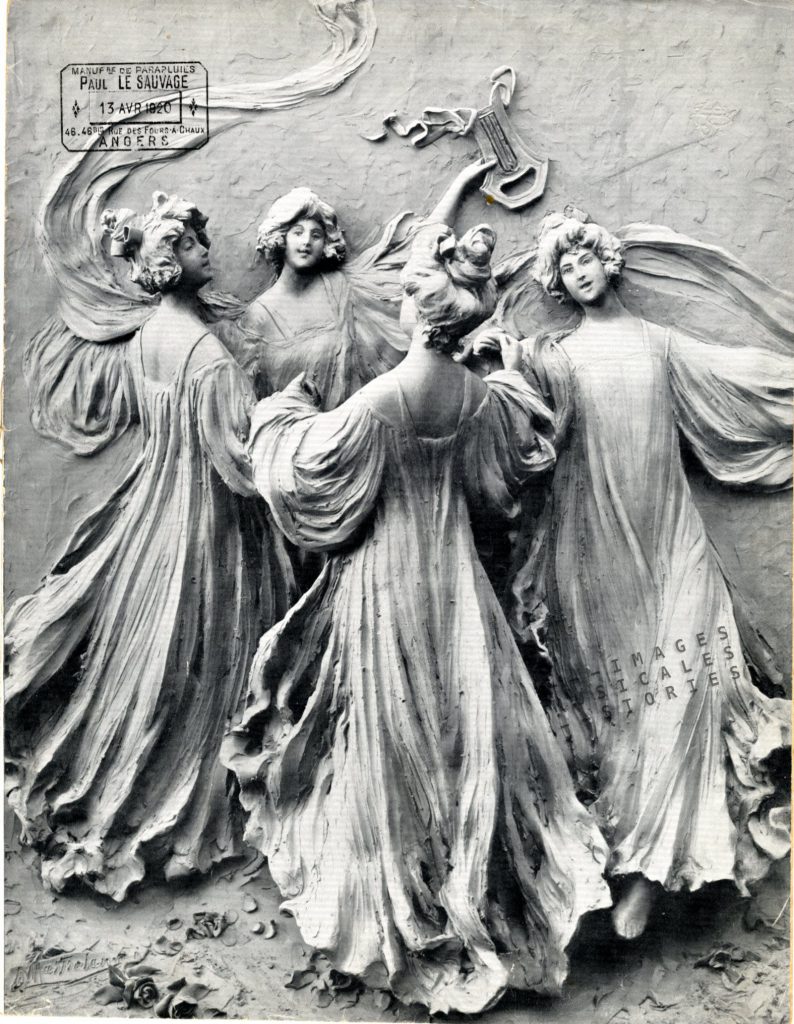

This cover shows a rare and original form of illustration. It bears no title nor composer’s name. Both (‘Chaconne‘ by Eugène Météhen) are printed on the inside together with the piano notation. The sheet music was commissioned by the Robinson d’Anjou, the retail store of a large umbrella factory in Angers, France. We admit that it is a rather campy collection item. But the storyline behind this unusual design deserves to be explored. As per usual, we cheerfully oblige.

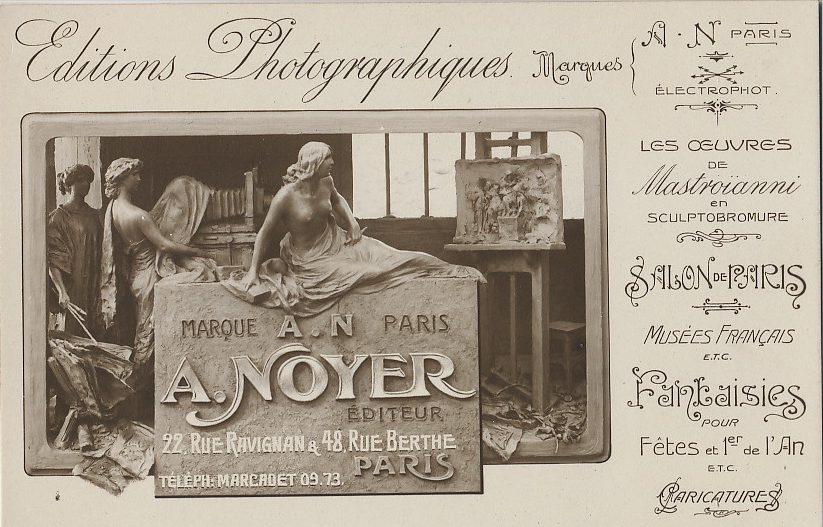

We discovered that the cover was created by Domenico Mastroianni, an Italian sculptor living in Paris. He became famous for his sculpture éphémère also known as sculptobromure or sculptogravure. Thanks to an advertising postcard from the prolific Parisian publisher Armand Noyer, we can have a glimpse of Mastroianni’s amazing technique.

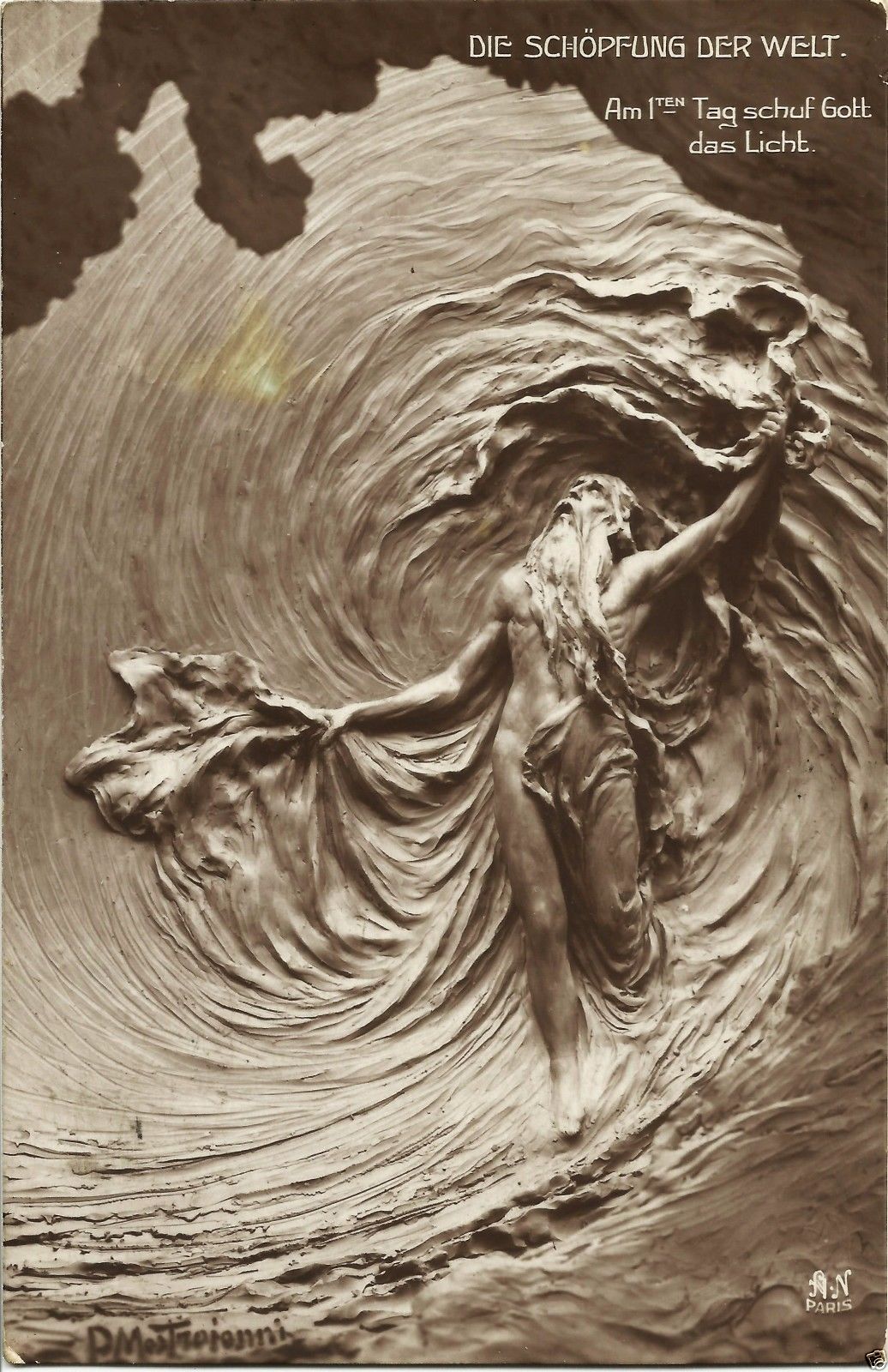

Firstly, and with astonishing speed and skill, Mastroianni modelled realistic reliefs on clay plates of about 50 cm x 70 cm. Then the plates where photographed, and these clichés were reproduced as postcards. As soon as a plate had been photographed, it was destroyed to prepare for the next scenes. Alas, not one of his plates survived.

With this method Domenico Mastroianni was incredibly productive. His printed kitsch makings flooded the French and international postcard market. Often his creations illustrated the lives of the most famous historical, literary, religious and mythological characters. But he didn’t shrink from fabricating risqué scenes in Art Nouveau style, sometimes taking bad taste to the limit.

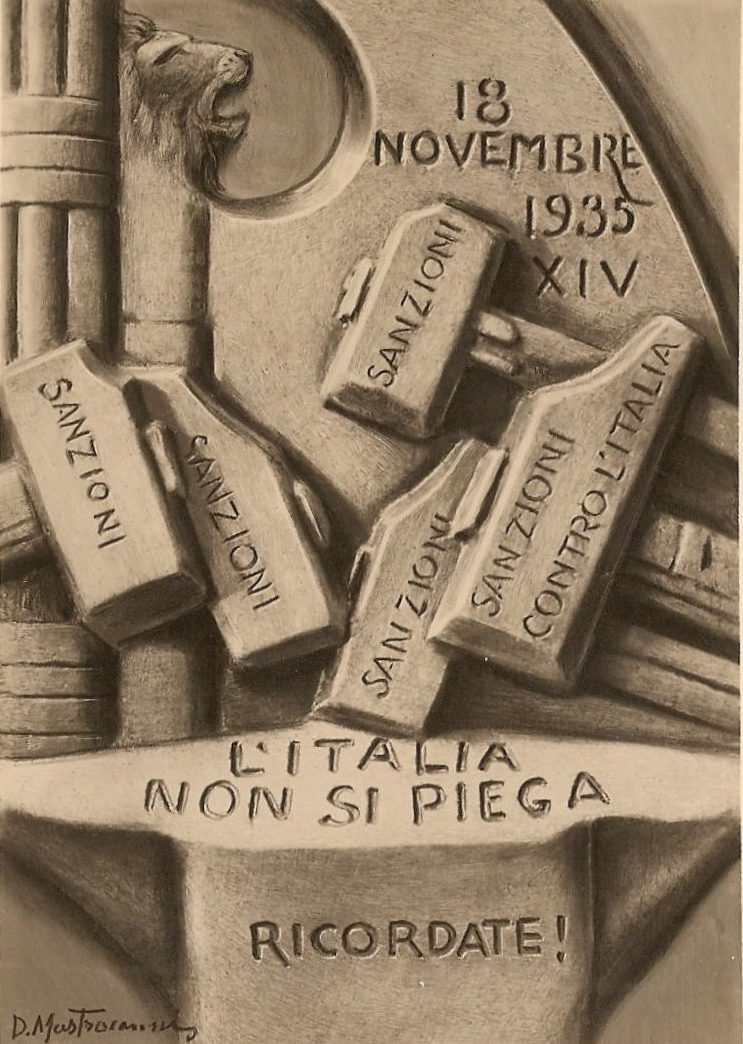

Just before the first World War Mastroianni returned to Italy where he continued his production of postcards. In 1935 our sculptor illustrated a propaganda postcard against the sanctions imposed upon Italy by the League of Nations. These sanctions targeted Italy’s invasion of Abyssinia (now Ethiopia) in that same year, when Mussolini was in search of a new Roman Empire.

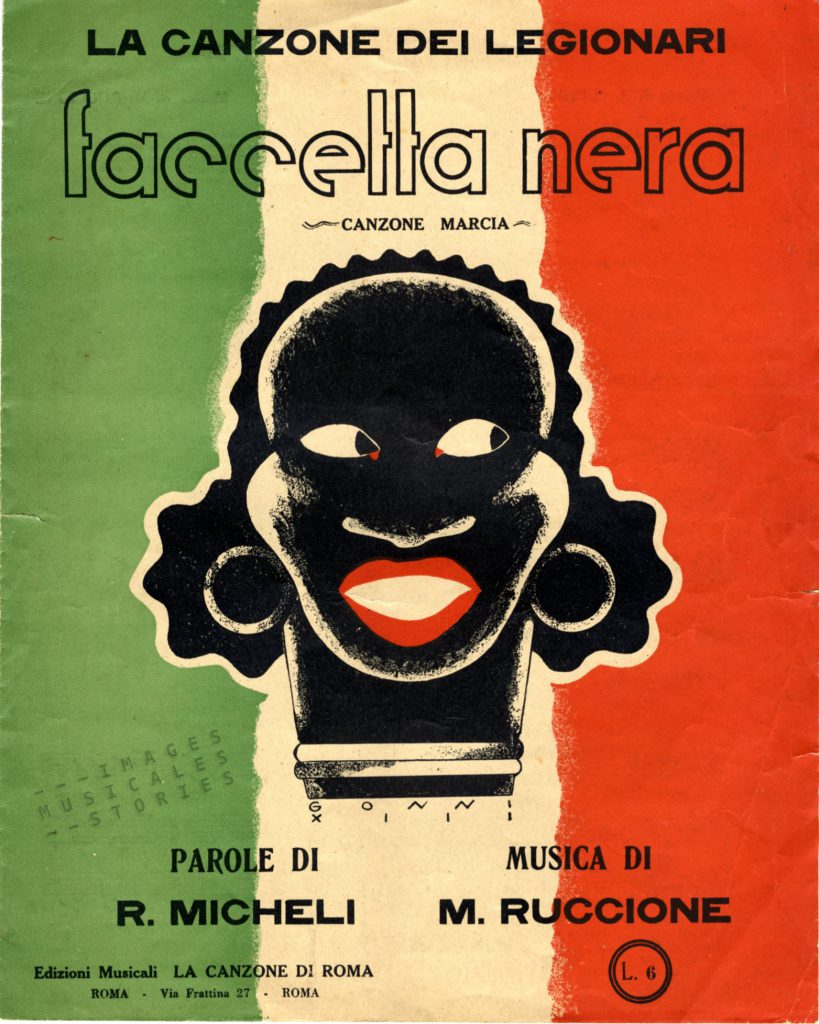

At that time a famous marching song accompanied Italy’s colonial adventure: Faccetta Nera (Little Black Face). The catching quickstep became very popular with the Italian armed Fascist militia, the Camicie Nere (Blackshirts) fighting in Ethiopia. The song describes an Ethiopian girl taken back to Rome by Italian troops after their invasion of Ethiopia. The young woman is paraded in front of Mussolini, herself also wearing the black shirt.

Although the song was written as a liberation song supporting the abolishment of slavery in Ethiopia (Mussolini’s explanation for his territorial expansion), it was without doubt a sexist and racist song and still is. In Italy, singing it today invokes controversy and its name is sometimes used as the N-word, to insult black women or girls. Even now on Youtube, there are Italian fascist aficionado’s who advocate their love for the song. It was beautifully illustrated by Gino Gonni though.

Mussolini despised the jovial tone of the text which called for a swift and painless integration of a young Ethiopian woman in Italian fascist society: “you will be Roman, your flag will be the Italian one”.

And Mussolini abhorred even more the implicit reference to interracial sex. However, to forbid the song would have been too drastic in view of its immense popularity among the colonial legionnaires.

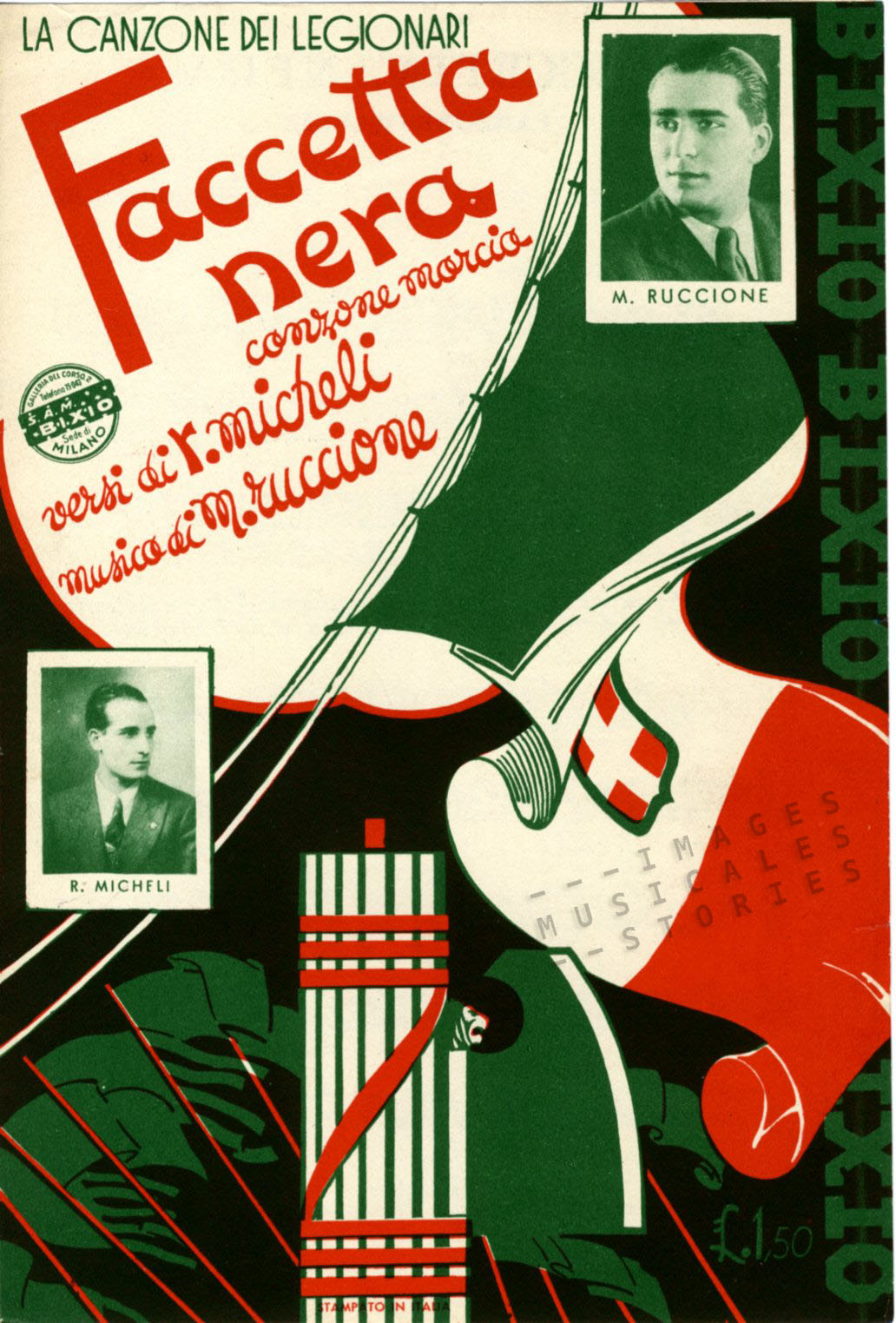

Instead, publisher Bixio came up with a more appropriate cover design, boasting suitable flags and the emblematic Roman fasces.

If the song could not completely be banished, at least it could be conveniently redacted. The initial text of Faccetta nera made a reference to the First Italo-Ethiopian War in 1896, a year when the Italian forces suffered great losses and Italy had to accept Ethiopian independence. This passage in the lyrics was censured because Mussolini didn’t want any reminders of defeat.

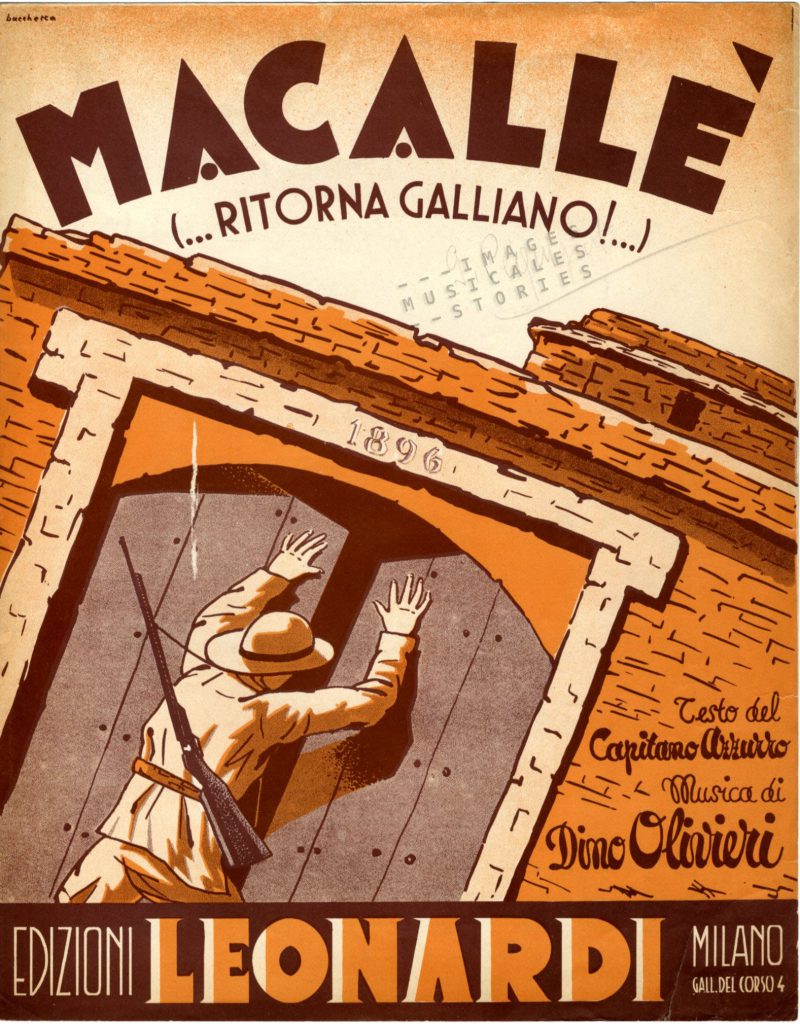

On the other hand, the reference to that humiliating year is very explicit on the cover of the song Macallè (published somewhat later than Faccetta nera). The central inscription ‘1896’ is carved on the door lintel. The explanation is that in 1935 on November 8th the Italian forces captured Mek’ele (Macallè): the previous defeat was now revenged.

With these fascist songs we’re a bit off topic now. So back to Domenico Mastroianni with a last lingering question: was he related to the great Marcello? Yes indeed! He was Marcello’s uncle’s uncle. Finally an excuse to slip Marcello Mastroianni in our blog.

I have a tattered print of one of Domenico Mastroanni’s aviation clay sculptures, and would like to obtain a better copy, but have been unable to find one so far. For interest, I attach a photograph.

‘Canto Abissino’ by A. Vitale & A. Maisani, published by Edizione Vitale (Brindisi, 1936).