The Satanella Valse on this Victorian cover is part of a romantic opera produced at Covent Garden in 1858. Satanella’s black dress, printed with the signs of the night, embodies evil: she is a female avatar of the devil. Mourning the loss of her love interest, she feels unable to compete with the purity of the love he has for another woman. His virtue is symbolised by the white and Christian marriage scene at the altar.

breathes Victorian morality: the Church, representing the ideal of the highest good, demands submissiveness, resignation and obedience to God. The atmosphere of the cover is strikingly different from the seductive French she-demon illustrated by Chatinière around the same period.

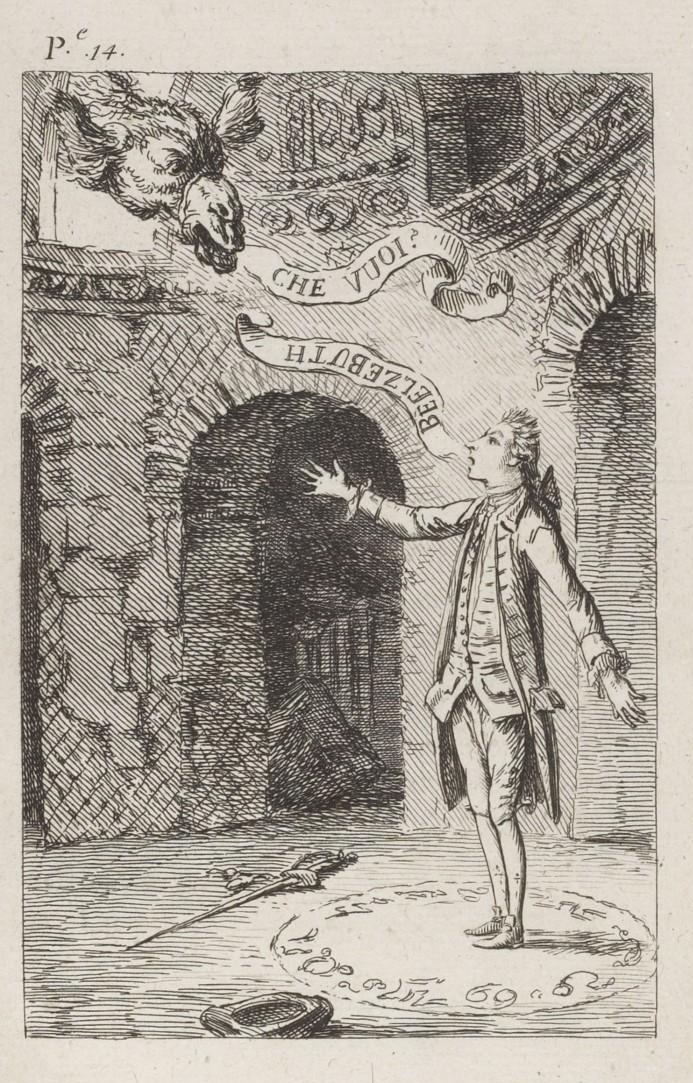

The pious story of the English Satanella opera is also in stark contrast to the original French novella Le Diable Amoureux (The Devil in Love) written by Jacques Cazotte in 1772. This is an occult story about a Spanish nobleman, Alvare, being seduced by the devil himself. When the story opens, Alvare brazenly summons Beelzebub who appears as the monstrous head of a camel asking Che vuoi?

The question ‘What do you want from me?‘ makes Alvare confident enough to start commanding the devil. Who obliges, because he just fell head over heels in love with the young man – If you ask me, it was only devilish lust.

In order to seduce Alvare, Beelzebub then willingly transforms from a camel into a cute spaniel and next into a beautiful, androgynous, young page. The page alternately morphs from one gender into the other. In his male guise, the ravishing Biondetto accompanies Alvare on his travels. Although Alvare feels attracted to Biondetto, it is the female avatar, Biondetta, who is intent on getting the virgin Alvare into bed. Alvare much captivated by her devilish charms, rejects her sensuous proposals: he first wants his mother’s approval to marry her. What a sweetie-pie! Or is it a ploy to camouflage his struggle with gender identity?

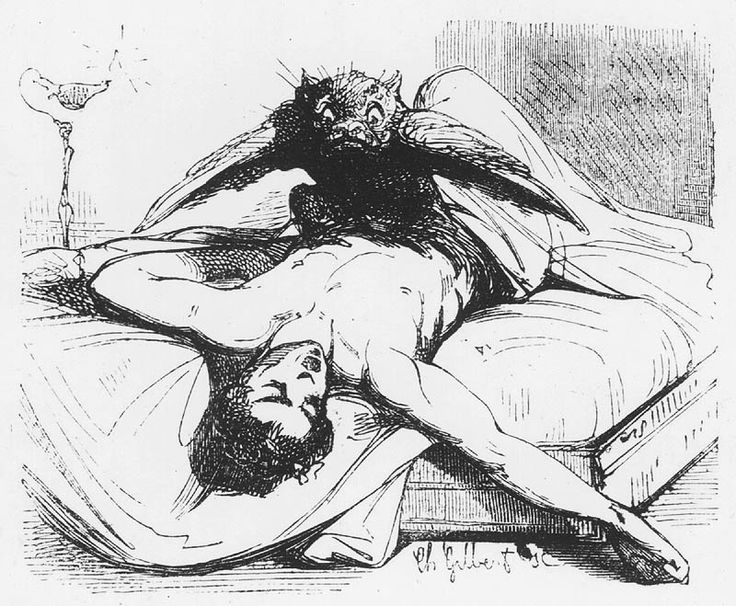

As the story winds up to its climax, the couple end up together in the same bedroom. Alvare’s prudish resolve weakens and he gives in to Biondetta’s sexual demands. After the moment suprême the demon takes on his normal Beelzebub appearance. Ha! that must have been quite a surprise for Alvare.

Curiously for an 18-th century author, Cazotte leaves the end of Le Diable Amoureux open: you can either construe the story as a phantasm, or as a moralising story. It is up to the reader to regard the story as a nightmare befalling the main character, or as a true story from which he is saved by a priest and his mother. I don’t care too much about the moralising message. Biondetta is an intelligent, untameable girl. She’s always able to cope, even when it means the use of a slight subterfuge. My sympathies definitely lie with the mischievous, diabolical heroine…

Le Diable Amoureux was one of the earliest occult novels. The story’s sexual and moral dilemmas must have fascinated the public during decades. This explains why it was adapted many times into several ballets, opera’s and songs. It is amusing that with each adaptation not only the names of the characters changed, but also the story’s moral message.

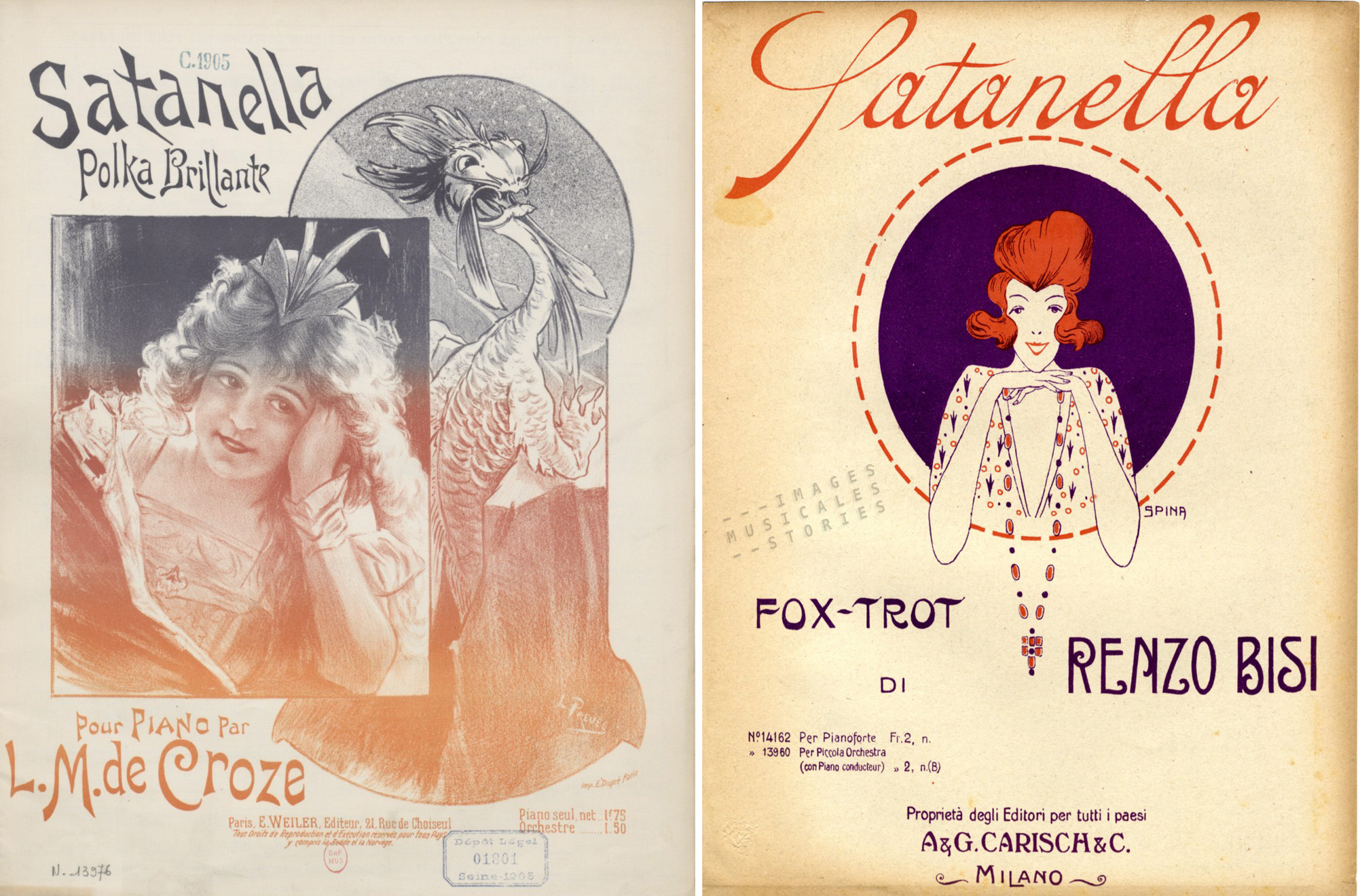

In the 20-th century Prevel illustrated a less moralising sheet music cover of Satanella for a polka inspired by Le Diable Amoureux. And for a 1920 Italian fox-trot, Spina created a modern and attractive Satanella-redhead.

Times and morals are always changing. But one constant is that creative illustrators have a soft spot for Satanella, Biondetta or other she-devils. Their message is clear: Watch out boy, she’ll chew you up!